In a year of isolation, we took solace in stories. And in a year of heartbreak, loss, and conflict, we sought understanding. These are the articles our online readers turned to again and again in 2020. We start at the beginning. Our top two reads open with photographs of their authors cradled in a parent’s arms, and ask, What shapes us early on? For Natasha Trethewey, it was an early lesson in metaphor. For Malinda Maynor Lowery, it was an understanding that Native history is American history.

Our next two reads plunge deeper into memory. Lisa A. Lindsay grapples with what it means to be a historian with a brain injury. “If memory tells us something about who we are,” she writes, “it also tells us about who we . . . were with. That is, it reveals human community.” Folklorist Michelle Lanier picks up this thread in her essay “Rooted,” as she looks at the Gullah/Geechee community that has grounded her from childhood.

And from the Documentary Moment Issue, two articles contained prescient advice for navigating 2020: making do with what’s at hand. Kate Medley created a temporary portrait studio at gas stations in the Mississippi Delta to photograph daily life. And Kimber Thomas talked to her grandmother’s community at the Crossroads, also in the Delta, about how seemingly mundane objects—forks, brown paper sacks, and tobacco tins—became tools for resistance and resilience.

Narratives, too, are tools of resistance. Jessica Lynne imagines the story within a snapshot she keeps close for comfort. “Like my debit card, lip balm, or driver’s license,” she writes, “this photograph has become part of my daily essentials kit.” In an interview, Priscilla Wald pushes against the ways we tend to talk about pandemics, offering alternative stories. And musician Skylar Gudasz calls upon fellow artists to create new realities.

Finally, as poet Nikky Finney stated at the year’s start, “The rug has been pulled.” There are lessons for all of us in her statement on Black resilience. And we must not emerge from this year the same.

1. You Are Not Safe in Science; You Are Not Safe in History: On Abiding Metaphors and Finding a Calling

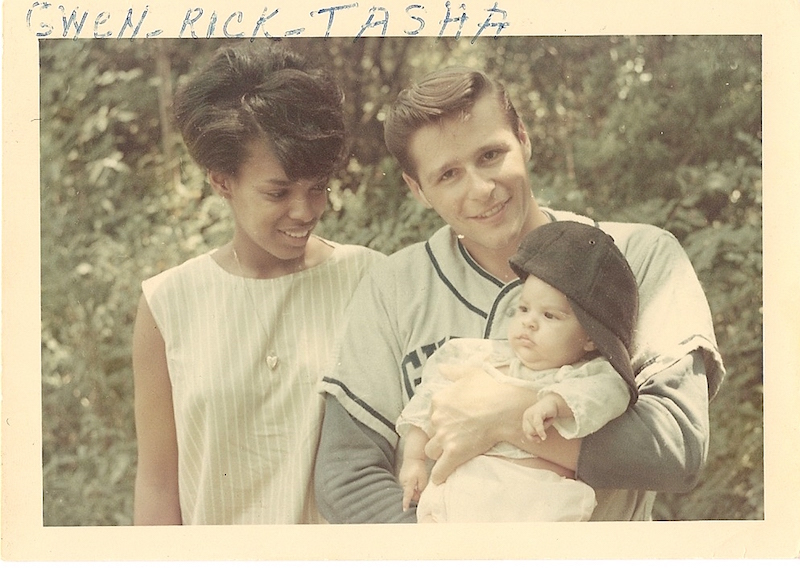

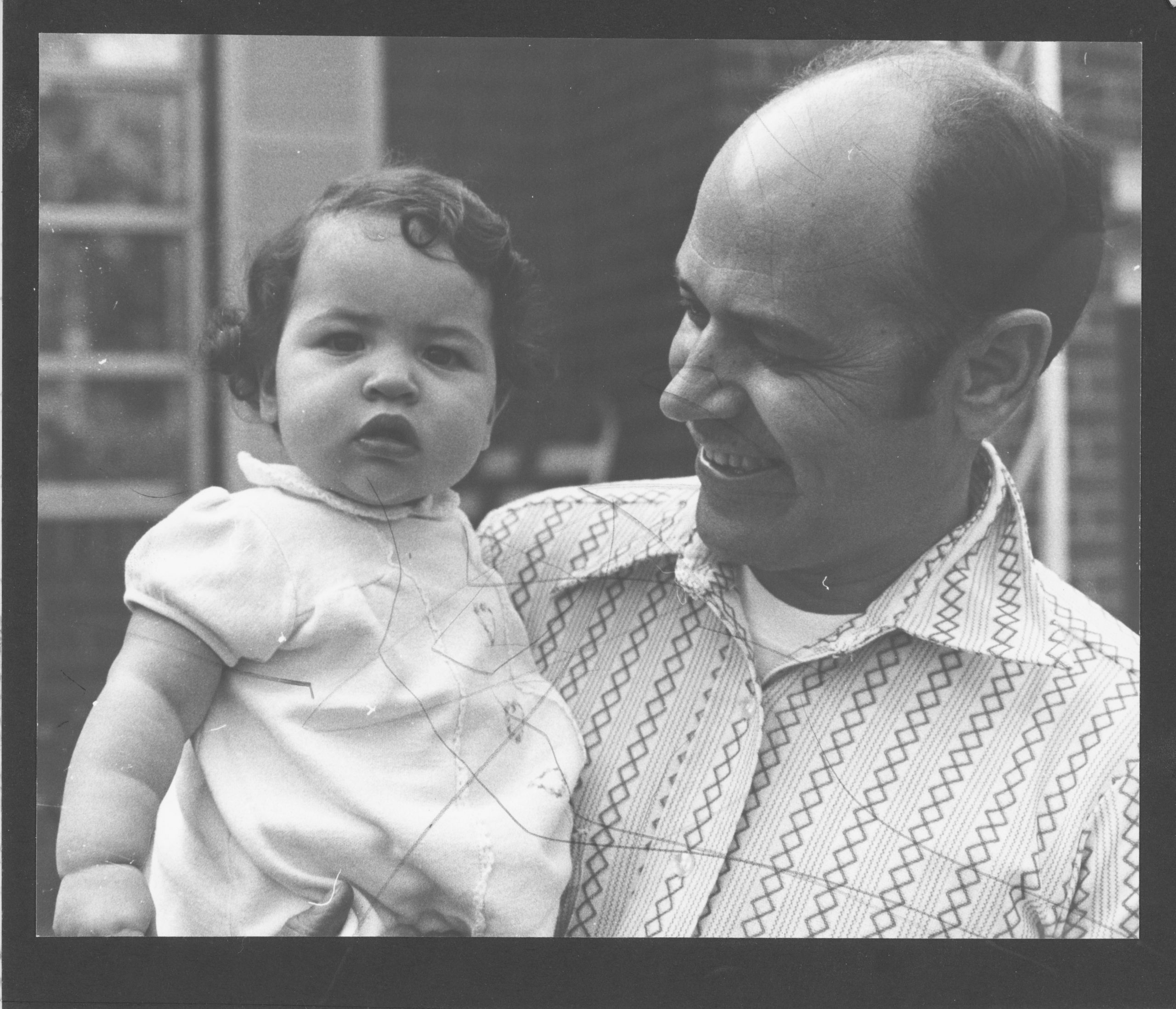

by Natasha Trethewey

I ask: what’s been left out of the historical record of my South and my nation? What is the danger in not knowing?

When I was three years old, I nearly drowned in a hotel pool in Mexico. My earliest memory is of what seemed a long moment, as if I were suspended there, looking up through a ceiling of water, the high sun barely visible overhead. I do not recall being afraid as I sank, only that I was enthralled by what I could see through that strange and wavering lens: my mother, who could not swim, leaning over the edge—arms outstretched—reaching for me. She was in the line of the sun and what she did not block radiated around her head, her face like an annular eclipse, dark and ringed with light.

It was 1969, a trip with my parents—my black mother, my white father. Looking back now I can see this is where it begins, what Robert Frost insisted was a necessary education, a proper poetical education in the metaphor, and the establishment in my consciousness of the abiding metaphors by which my work as a poet is always influenced. Beyond my vivid memory of nearly drowning—an image to which I’ll later return—only one other image of the trip remains: a photograph. In it, I am alone, there are mountains in the distance behind me, and I am sitting on a mule.

2. The Original Southerners: American Indians, the Civil War, and Confederate Memory

by Malinda Maynor Lowery

Being left out of the history and the commemoration of the Civil War is ironic, given that non-Indigenous Americans live on Indigenous land at all times.

When Robert E. Lee met Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox in 1865, Grant introduced Lee to his personal military secretary, a man named Ely S. Parker. At first, the story goes, Lee refused to shake Parker’s hand, mistaking his darker complexion for that of an African American soldier in Union blue. But Parker was not black, he was Tonawanda Seneca, a member of the Iroquois Confederacy from New York; realizing his mistake, Lee stepped forward and offered his hand: “I am glad to see one real American here,” he said. Parker simply extended his hand and replied, “We are all Americans.”

What did Lee mean by “American”? He invoked a definition of nationhood that the ancient Greeks and Romans and, later, the Nazis, also claimed: one was an American by virtue of one’s pure “blood” (a claim that one’s ancestors all belonged to the same “race”) and inalienable attachment to soil (or, the territory which white southerners, then and now, claimed they waged war to protect). Notably, some of the white supremacist groups at the August 2017 “Unite the Right” riot in Charlottesville, Virginia, chanted “blood and soil” as they protested the planned removal of Lee’s statue. Going back to before the Sons of Liberty at the Boston Tea Party, white Americans have used Indians to articulate their claims of righteous authenticity. This connection between “blood” and “soil” may be the reason Lee claimed a kind of affinity—however bitter—with Parker. By his own definition, Lee—obviously the descendant of immigrants—could not be an authentic American, except by erasing the land’s original inhabitants, one of whom was standing right in front of him. While black inequality was a cornerstone of the Confederacy, blood purity was not. In affirming his connection to a logic of blood and soil, Lee was rewriting history in his moment of surrender.

3. Memory Fieldwork: How a Historian Grappled with Brain Injury

by Lisa A. Lindsay

If memory tells us something about who we are, it also tells us about who we are or were with. That is, it reveals human community.

The earliest thing I remember after the hemorrhage is a moment that I can’t place in time and that may not have even happened. I was taken into a hospital room in Wilmington, North Carolina, guided there by my friends Christian and Jonathan, who were visiting me. As we stood in the entrance to the room, I looked at my partner Matt, who was stooped over a table filling out forms. Christian or Jonathan earnestly told me that Matt was taking good care of me; that he was showing himself to be what everyone already knew him to be, a good man who loved me.

A few weeks later, my friend Leila and my daughter Amelia were with Matt and me when my hairdresser came to my hospital room in Chapel Hill. Matt had found her contact information in my phone and arranged for her to confront the tangled mass of my long brown hair, practically impossible to penetrate after the weeks I had spent lying in bed. Who could think about brushing my hair when I might never wake up? But now I was awake, grimacing with every pass of the comb and eyeing both Leila’s and Amelia’s short, boyish hairstyles. “Just cut it off,” I decided. The resulting pixie haircut was kind of cute, I think I thought—but alas, half of it was buzzed off the next week, when surgeons unexpectedly opened my head for a second surgery.

After that operation—to install a drain for excess brain fluid—I remember things normally. But whatever I might have remembered for four weeks before it, with only these two exceptions, is gone.

4. Rooted: Black Women, Southern Memory, and Womanist Cartographies

by Michelle Lanier, with photographs by Allison Janae Hamilton

I was determined to remember. And I did.

Salt water flows in my veins, and I can recall my first taste of the Atlantic Ocean at two years old. I grew up hearing stories of how a six-year-old boy and girl, my maternal grandparents, met on a sandy South Carolina road and first experienced the spark that created my extended family. On this same road, Hurricane Hazel would one day claim Aunt Nette’s beach house, which she, the family’s matriarch, had proudly built in the all-Black resort town. Undeterred by that loss, that same boy, now grandfather and patriarch of the family, would awaken the whole house—sometimes neighbors too—and start a journey at 4:00 a.m. on a whim. We would all pile with our pillows into the wood-paneled station wagon and head for Atlantic Beach.

We were beach people, but we were not from the beach. I was a child of the beach only in that I knew how to dance on sand, eat crab, and ride waves. We would return there, sleeping three or four to a bed in Black-owned hotels, visit the Black dentist’s widow who stayed for weeks, go to the arcade to flirt and groove, and, over the years, bring the cremated ashes of our own, including my mother.

Years later, some of us would return to take photos of our children with the town’s historic sign, which proudly declares Atlantic Beach, South Carolina, as the “Black Pearl of the Grand Strand.” But we had never truly lived there. To the coastal Black world, we were outsiders from the Midlands who would come to visit the sea and then return to the center of the state, where we bought fish for Friday’s dinner at markets rather than catch it ourselves.

5. Gas Station South

by Kate Medley

It’s the first time in thirty years that someone’s made my picture.

David Williams takes a break from changing the oil on a customer’s car at Abney’s Store in Sunflower, Mississippi, to walk over and inquire about the canvas I’ve strung up along the periphery of the service station. “I’m photographing people at gas stations around the South,” I explain. “Would you like to have your picture made?”

We all take part in the seemingly mundane act of going to the gas station—whether to fill up our tanks, relieve our bladders, grab a cold one on the way home from work, buy live bait, or take advantage of Friday night’s “prime rib special.” In an increasingly atomized world of mediated interactions, we have fewer and fewer communal spaces in which we share a common experience. It is this unique commonality of passing through the same corridor that I seek to capture by setting up a makeshift photography studio on the shady side of an asphalt lot at rural gas stations across the American South.

Williams steps onto the canvas. His boots leave a streak of black oil. He gazes off toward the infinite horizon of the Mississippi Delta while I fire off a few frames. As we wrap up, Williams shakes my hand and says, “It’s the first time in thirty years that someone’s made my picture.”

Makeshifting: Black Women and Resilient Creativity in the Rural South

by Kimber Thomas

[These] women were engaged in an ongoing, material experiment of how to be together and live together in their world, at the Crossroads.

Mamie Barnes was the first Black woman to own land at the Crossroads. Her lot was right below the four-way stop, down the fork and to the left, directly in the sun, in God’s spotlight. Her neat, white shotgun house had a white, wooden screen door that led to a screened-in porch and a white, wooden porch swing—the perfect prelude to the inside—and all around us was beauty: pink roses and petunias, ripened okra and purple eggplant, collards and cucumbers, stems crisscrossing, like braided hair.

Inside we sat on her red sofa, planted our feet on the beige linoleum floors, and prepared to talk about rural Black women’s beauty practices during the early twentieth century—hairstyling in particular. I was eager to drown out the sounds of Steve Harvey’s Family Feud and the box fan blowing in the background, but no matter the topic, the time or the place, when “Steve Harvey” was on, the women I interviewed at the Crossroads neither turned off the TV nor lowered its volume.

“The hair.” Mamie, my grandmother, always began our conversations by stating the subject, as if to remind both of us of the matter at hand. “Now, when I was little,” she said, “I do remember that Mama couldn’t comb my hair. I had real thick hair.” She elongated the real, emphasized the thick. “And Mama said she’d take a fork and straighten it out where she could plait it. And then she—” Mamie paused to reflect. “I don’t know what come of it, but I had hair.”

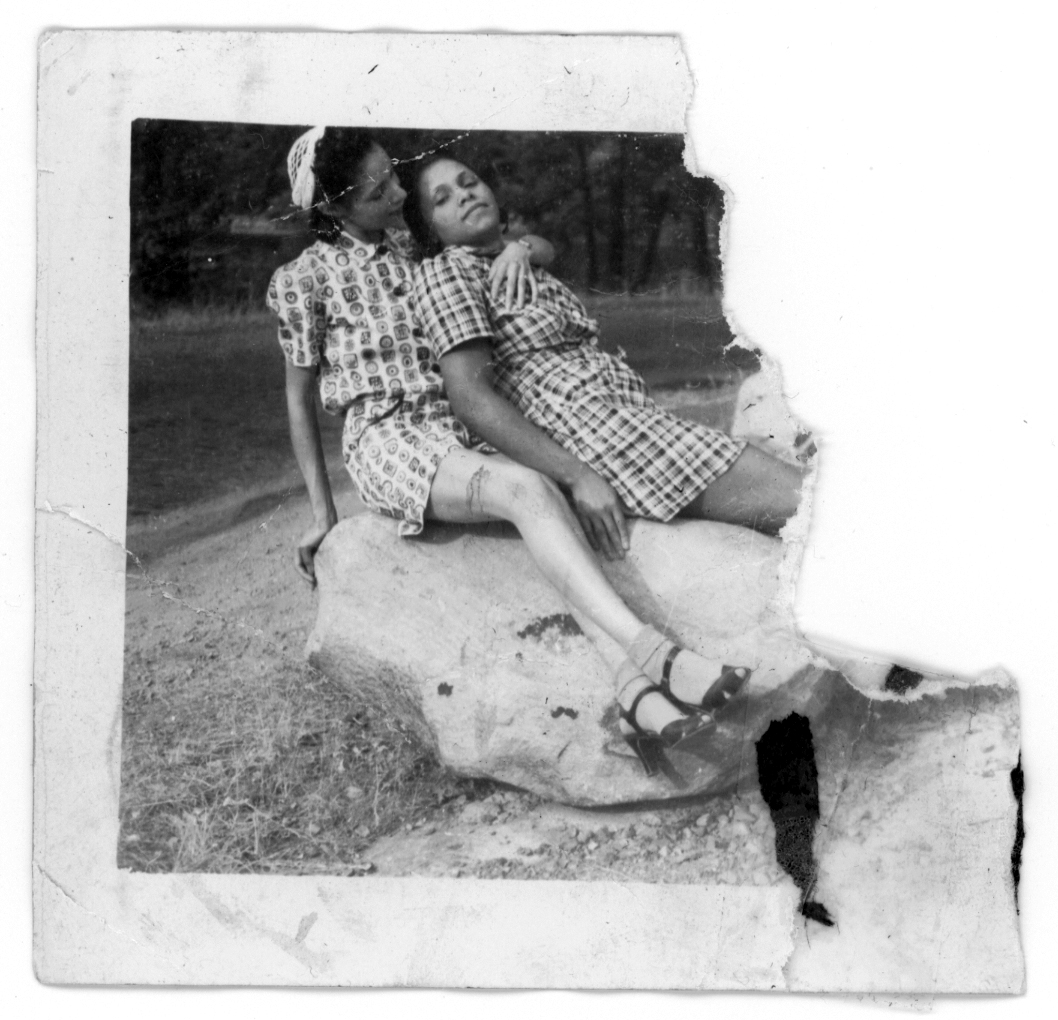

“That Which We Are Still Learning to Name”: Two Photographs of Black Queer Intimacy

by Jessica Lynne

They have come to this afternoon prepared to immortalize an intimacy.

I have carried a photograph on my person for the past year now. Like my debit card, lip balm, or driver’s license, this photograph has become part of my daily essentials kit. In the black-and-white image, two women clad in patterned and madras print dresses and low kitten heels sit on a rock and embrace casually yet lovingly. One woman rests against the chest of the other, wrapped in the arms of her companion. The woman who is held gazes directly and assuredly at the camera. The other woman looks softly at her companion. It is as if they have been preparing for this moment of capture. Here is the sun, they might have said. It’s best for us to sit this way. You are almost there. A friend, a loved one, a sister, or an aunt steadying their hands on the camera.

The two women wear the expressions of people who know one another well. They hold one another’s secrets. They have been lost in winding conversation on a leisurely afternoon. They have just finished a walk through the park. They have joined friends for a gathering or celebration. They have come to this afternoon prepared to immortalize their intimacy. This photograph is not dated nor is there any indication of location or who these women might be. Behind them, an expanse of land. Perhaps a path or a picnic area. I cling to this photograph.

COVID-19 and the Outbreak Narrative

by Priscilla Wald and Kym Weed

The outbreak narrative is the narrative about fear and panic and so on, but it’s also a narrative of reassurance.

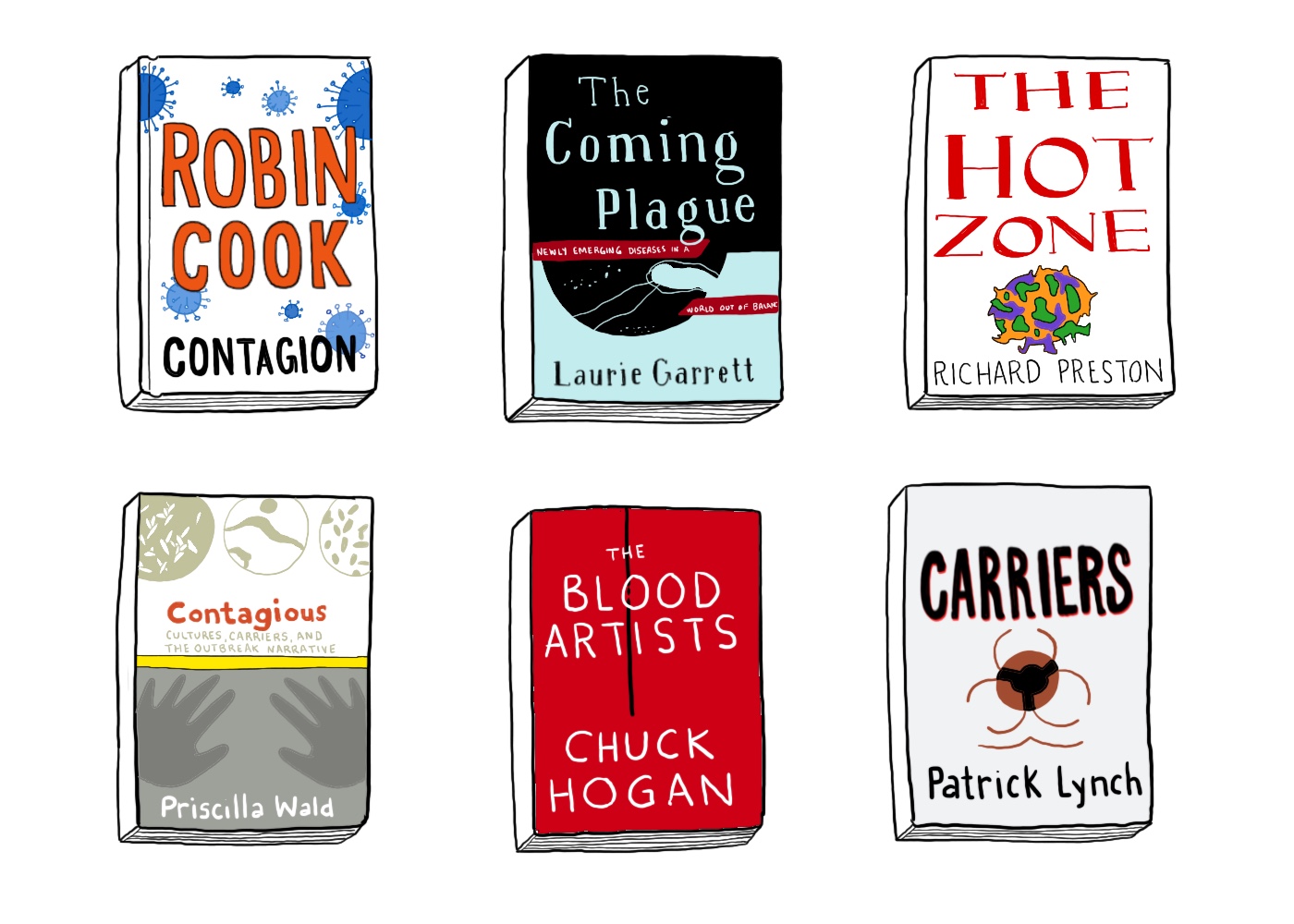

In her 2008 book Contagious: Cultures, Carriers, and the Outbreak Narrative (Duke UP), Priscilla Wald identified a cultural narrative of emerging infections circulating in scientific, journalistic, and fictional accounts of infectious disease that she calls the “outbreak narrative.” This narrative, which follows a formulaic plot of disease emergence, identification, and containment, gained popularity in the 1990s and has continued to shape how scientists and the public alike understand catastrophic epidemic disease. It has material consequences that range from stigmatizing groups or locales to changing economies and affecting survival rates. In the midst of a global pandemic, the outbreak narrative informs not just how we talk about infectious disease but also how we respond to it. On April 2, 2020, Kym Weed spoke with Wald by phone to learn more about what the outbreak narrative can teach us about the COVID-19 pandemic, from the interconnectedness that infectious disease calls up the modes of disease prevention that it precludes.

Wild Heirloom: A Meditation Through Time

by Skylar Gudasz

The South is a ghost, a ghost is a lie.

1. When I was five and my brother Jason was three, we lived in an old white farmhouse near the James River in Varina, Virginia. I was too young to believe in the idea of ghosts; otherwise, I’m sure I would have been convinced I was seeing them in every dusk-dim corner of the property—by the old Steinway at the foot of creaking wooden stairs, in the shadows of tall door frames, along the yellow fields of broomsedge stretching up to the giant robot army of power lines marching forever toward the big city of Richmond.

2. “I don’t remember any ghosts,” my brother offers at a family dinner in 2019. Grown now, Jason is a filmmaker and I am a songwriter, and our returns home are rare and often loud with conversations about family and memory. And, inevitably, also politics.

“You remember that place? You were so young.” I find it hard to believe that my brother remembers the white house at all. “What years were we even there?” I ask our mother.

“I was so afraid you all would wander back under the power lines,” my mother says, bringing her hand to her head and evading the specifics of the question, consumed with guilt. (This is a woman who has never owned a microwave for fear of what radiation may or may not do to the human body.)

10. The Rug Has Been Pulled

by Nikky Finney

They are invisible without the ‘i.’

“It’s not one thing. It’s the total destruction of Black humanity . . . The only thing that revives it, that keeps coming back, is Black memory. We will not die. There are Black people in the future.” Poet Nikky Finney, UNC’s 2020 Frank B. Hanes Writer-in-Residence, from the panel “‘Blacker than a hundred midnights’: Public History and Memory and the Souls of Blackfolk in the South.”