Confronted with another year of the pandemic–another year of heartbreak, isolation, and resolve–we turned to imagination. We launched the year with an issue on the Imaginary South, guest edited by the esteemed writer and sociologist Zandria Robinson. “There are Souths that are only imaginary because most dominant stories about the region do not acknowledge they exist,” Robinson wrote in her introduction. And, of course, that statement is true beyond the bounds of the region, and the shaky ground of 2021 led all of us to seek solace and solidity, both real and imagined.

Our top 10 essays for the year start with the ground, moving from ruin to reclamation and reaching for portals to new worlds. Grounded in family lore and bracing against political distortions, our authors expand the archive into one of shared community.

As we start this new year, we know we aren’t out of the woods yet. So we will keep imagining, keep seeking. “The investigation was infectious,” Cassandra Klos writes in her essay on Bigfoot. “[I]n a short time, I was looking for similar things myself, scouring the grounds for markings, ready to believe.”

1. “To Live and Thrive on New Earths”: The Earthseed Land Collective and Black Freedom

by Danielle M. Purifoy

From an old wooden swing, Zulayka Santiago heard the over-revving of another truck speeding down the main road in front of her house. It was a not-too-warm day in May 2020, and we were at the tail end of our nearly hour-long interview. We tried to escape the noise by sitting near the treehouse where she hosts meditation classes. Taking coronavirus precautions, we couldn’t go indoors, so we kept our distance outside, masks off.

Earthseed represents a version of the alternative world Octavia Butler imagined.

Her eyes widened at the truck’s roar and she interrupted what she was saying to turn toward the busy road. Ever since she and her family landed here at Earthseed Land Collective, forty-eight acres in Durham, North Carolina, co-owned by herself and six other Black and Latinx people, Zulayka said she’s been taking opportunities to embrace not only the challenges of building deep, lasting collaborations with fellow Earthseed members, but also confronting mundane disruptions of her mostly quiet life here.

“It is so important to me to choose what I focus my attention on,” she said, turning back towards me, “so even in the midst of all that noise and chaos, [Earthseed] continues to be a sanctuary for the frogs, for the dragon flies, for the birds, for me.”

2. Two Rivers

by Alexis Pauline Gumbs

Go to Tougaloo, the meeting place of two rivers, and be quiet. Wait for the light that floats above the water where Pearl meets Mississippi and step in it. If you are too afraid to trust the light, to know yourself as more than one river, you will never know. Step in when you are ready.

What two rivers agree upon when they meet is the ocean. Their destination. Their longing. That pull.

When you step into the light it is loud, but keep breathing. You will hear what sounds like an ocean of singing, thousands of renditions of “This Little Light of Mine.” Stay still until you know that the light holding you came from within. Let it shine.

This is a portal thousands of years old. Cool from the people who stayed offering centuries of Choctaw care. Smooth from the running of water. Stealth from the breath of the free people who refused to be held by enslavement. It is enough that you are here in this moment. Feel that multitude.

3. The Making of Appalachian Mississippi

by Justin Randolph

In 1966, a retired high school principal named George Thompson Pound reached for his Rand McNally atlas. He turned to page six, took a pen, and drew off Appalachia. Starting in West Virginia, he marked along the Blue Ridge Mountains, through the Carolinas, northwest Georgia, and east Alabama.

There was just one problem: Mississippi lacked mountains.

But Pound kept going. He marked past the clear end of mountainous terrain around Birmingham, Alabama, and passed into North Mississippi—his home. With the stroke of a pen, Pound boldly reimagined geography and race in one of America’s most notorious Jim Crow states. He fused the imaginative work of region-making and mapmaking into a lasting political reality for the land and its people.

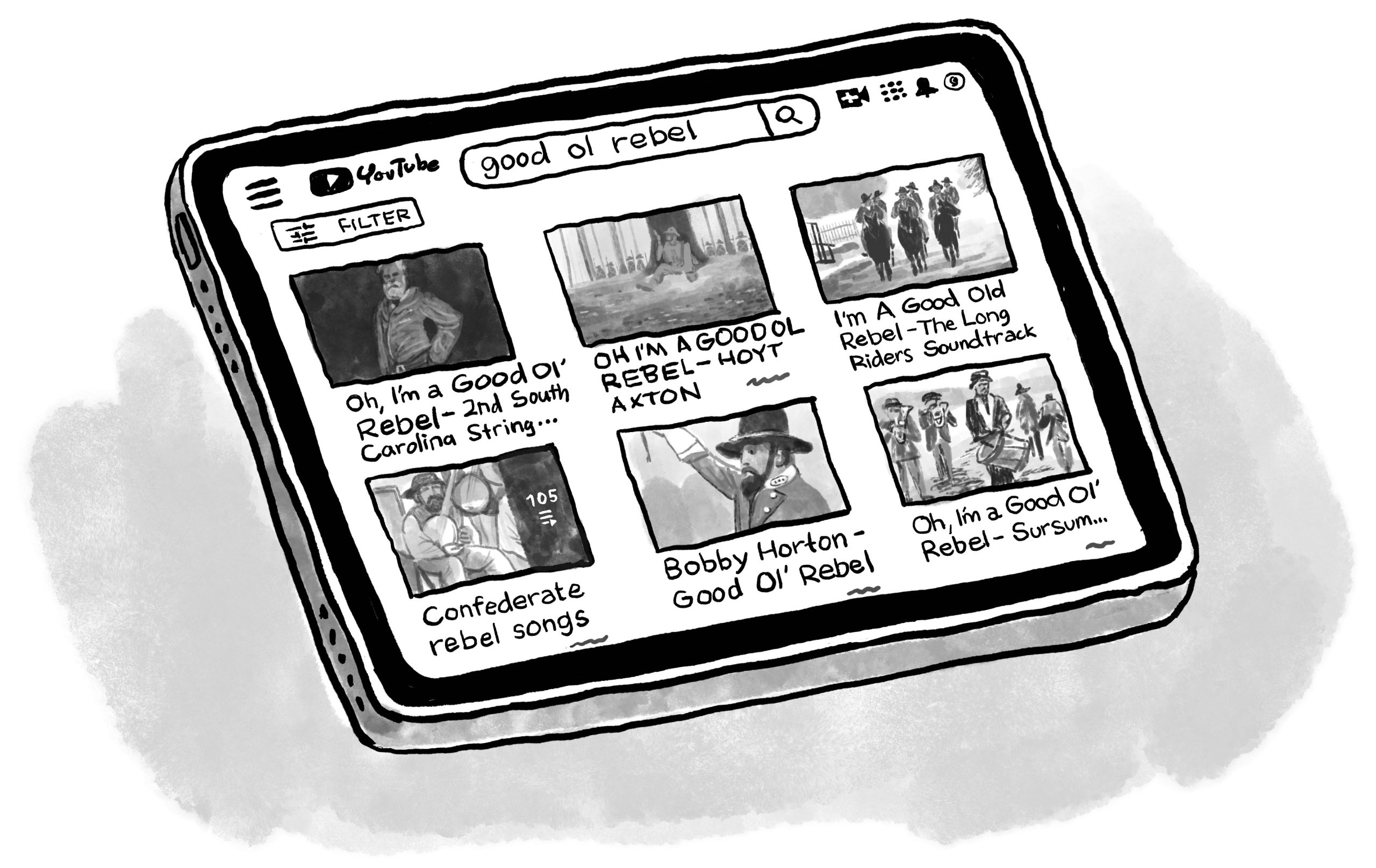

4. The “Good Old Rebel” at the Heart of the Radical Right

by Joseph M. Thompson

On July 4, 1867, Augusta, Georgia’s newspaper, the Daily Constitutionalist, published the words to a new song that seemed to reflect the bitterness felt by many white southerners following the Confederate defeat. The paper printed the song’s title as “O! I’m a Good Old Rebel” above a spiteful dedication to Thaddeus Stevens, the abolitionist congressman from Pennsylvania. It also provided the instructive subtitle “A Chant to the Wild Western Melody ‘Joe Bowers,’” letting readers know they should sing the lyrics to the minor-keyed folk tune to give “Good Old Rebel” a mixture of melancholy and menace. The paper did not include an author attribution, but given the first-person perspective, the unpolished vernacular, and the tone, it appeared that a recalcitrant Confederate veteran had penned the lyrics. This anonymous author seemed to cling to his identity as an unrepentant traitor who twists failed rebellion into victimhood. He begins, “O I’m a good old Rebel, / Now that’s just what I am; / For this ‘Fair Land of Freedom’ / I do not care at all,” with the italicized “at all” censoring an obviously rhyming but omitted “damn.”

“Good Old Rebel” also failed to achieve Randolph’s literary goal, as it escaped the circles of his educated peers. By the late nineteenth century, the song belonged to and appeared to speak for the very people it mocked.

The next four verses took the denunciations of the United States even further. “Good Old Rebel” inventories all of the nation’s founding documents and symbols that he hates, including the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the US flag, as well as the Freedmen’s Bureau, the agency created in 1865 to implement the plans of Reconstruction and help formerly enslaved African Americans transition to liberty. The author casts himself as a victim of postwar oppression while claiming he would like to “kill some mo’” US soldiers. In the final verse, he pledges to never accept Reconstruction, claiming, “And I don’t want no pardon, / For what I was and am; / I won’t be reconstructed. / And I don’t care a cent” [another omitted “damn”].

5. The Most Caribbean of Stories

by Maya Doig-Acuña

I was in college when I first learned that my great-grandmother, Lydia Andrews, who my father and his siblings and cousins called Ganny, was born on the United Fruit Plantation in Puerto Limón, Costa Rica. Before Papi shared this fact with me, I knew Ganny only in small glimpses of family memory that seemed to contract the world in which she existed, such that she existed only in ours—that is, she belonged specifically to my family, and not to history.

I knew Ganny only in small glimpses of family memory that seemed to contract the world in which she existed, such that she existed only in ours—that is, she belonged specifically to my family, and not to history.

We had briefly shared this world—between 1994, when I was born, and 1998, when she died—though we never met, because she lived in Panama and I in Brooklyn. But I had seen photos of her: mostly sepia-toned images of a dark-skinned, white-haired woman with glasses, a nose like my father’s, and a graceful neck that made her the center of each picture. There was one photo in vivid color taken just a few years before her passing, in Coronado, Panama. She sat on a chair surrounded by our family, wearing a red dress patterned with white flowers, her hands folded on her lap.

When Ganny died, my grandmother went to Panama for the funeral, and on her return to New York, brought me back a purple stuffed beaver named Benny that she said Ganny had gotten for me. And though it wasn’t possible—though Ganny and I no longer occupied the same world—I believed her, and treasured the beaver like an intimate conversation between me and my great-grandmother.

6. The Lake and the Landfill: In Search of Atlanta’s Lake Charlotte

by Hannah S. Palmer

Lake Charlotte started to bother me one summer while I was working on a freelance project with a nonprofit called Trees Atlanta. Somewhere in the organization’s sunny building, I saw a poster illustrating Atlanta’s tree canopy—a kind of heat map of trees that needed saving. Red-orange blocks downtown sprawled into yellow-green neighborhoods and green parks. I studied it while waiting for my meeting to begin, amused to see the typical city map in reverse, defined by its undeveloped pockets instead of highways. The deepest green was in the southeast corner of the city, an emerald parcel bounded by a landfill and I-285. I knew what it was—Lake Charlotte Nature Preserve—but I had never been there.

Instead of expanding outward, the landfill rose like a loaf of bread—a rotten rectangle squeezed straight by the county line and the interstate.

According to this map, the forest was larger and greener than Piedmont Park and Grant Park combined. I tried to picture it and came up blank. All I remembered was the forbidding landfills and barren truck lots clustered in the elbow of the interstate. Old junkyards, strip clubs, and public housing projects scattered along Moreland Avenue. Long before I knew about zoning, I recognized the land-use pattern that sited poor Black neighborhoods alongside industrial districts. For most of my life, I had avoided this area, home, apparently, to the single largest concentration of intact tree canopy left inside the city limits.

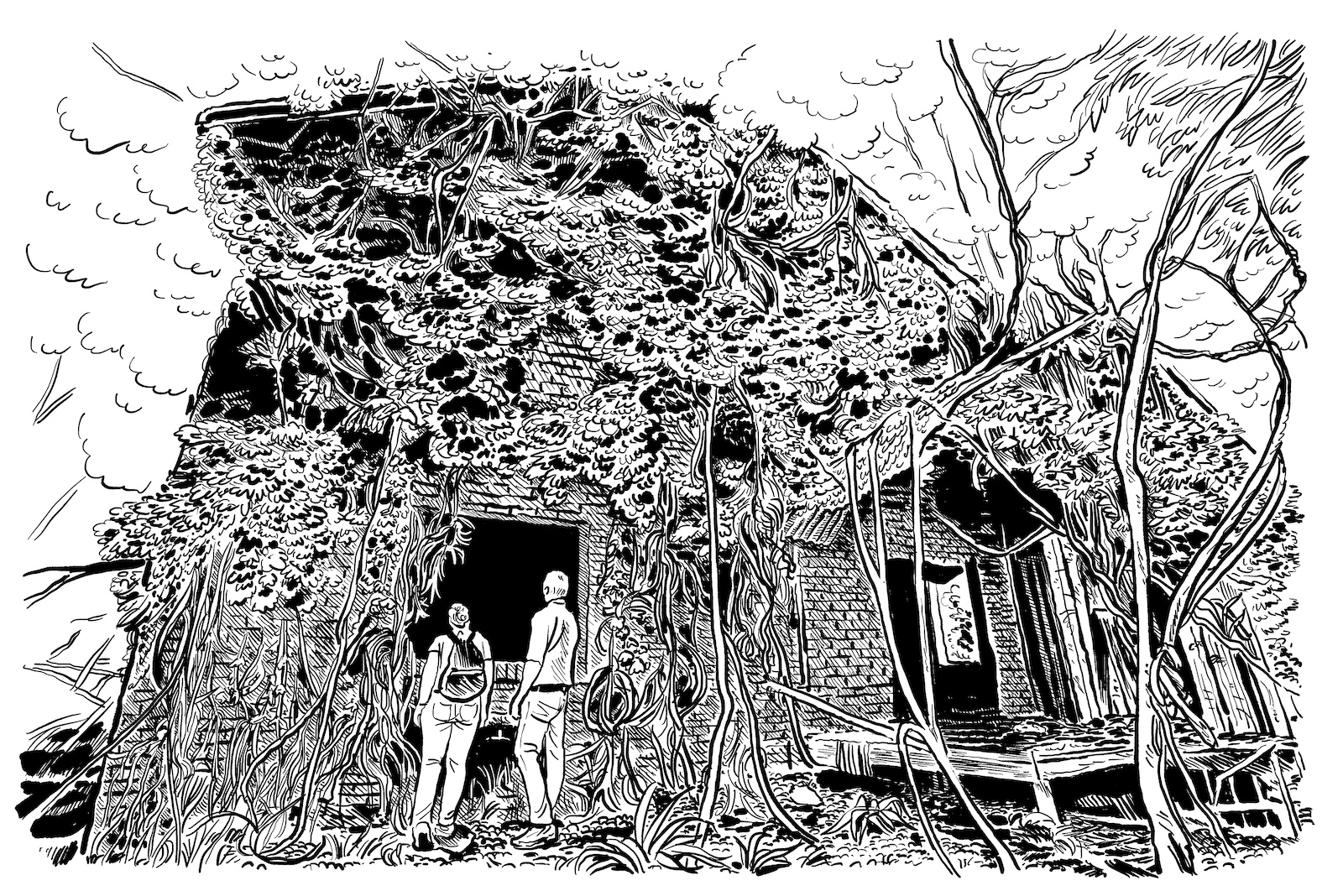

7. Looking for Bigfoot

by Cassandra Klos

Driving south on I-85 from Richmond into North Carolina, the trees begin to envelop you. Not being from here, I am seduced by that wilderness. It’s like entering an open storybook, a deep trove of mythologies and histories built into the landscape and etched into memory from the stories of others, both recent and generations past. And for some, these stories are not myths.

The investigation was infectious, and, in a short time, I was looking for similar things myself, scouring the grounds for markings, ready to believe.

From my home state of New Hampshire to my new home in North Carolina, I had a simple hope to explore and understand the latter through their commonalities: the deep forests and rising mountain ranges, winding waterways, and abundance of roadside Cracker Barrels. In the rural stretch between Durham and Charlotte, North Carolina, is the fifty thousand-acre Uwharrie National Forest, named for the Indigenous tribe that once inhabited the mountains there. While researching North Carolina forests to explore, Uwharrie started to become synonymous with what I could only imagine to be a joke: Bigfoot sightings. It seemed I could not search for advice on traversing the Uwharrie range without coming across mentions of where this mythical creature could be found. Before long, I became entranced by stories and blurry photographs in online groups for Bigfoot enthusiasts. There are many: Bigfoot 911, North Carolina Bigfoot Investigations (NCBI), Bigfoot Campfire Stories, Squatcher X, Squatch Watchers, Dirty South Squatchers. The list goes on, ranging from forums of thousands of active members to neighborhood sightings, all with one common goal—to prove the existence of this elusive creature.

8. In Search of Maudell Sleet’s Garden

by Glenda Gilmore

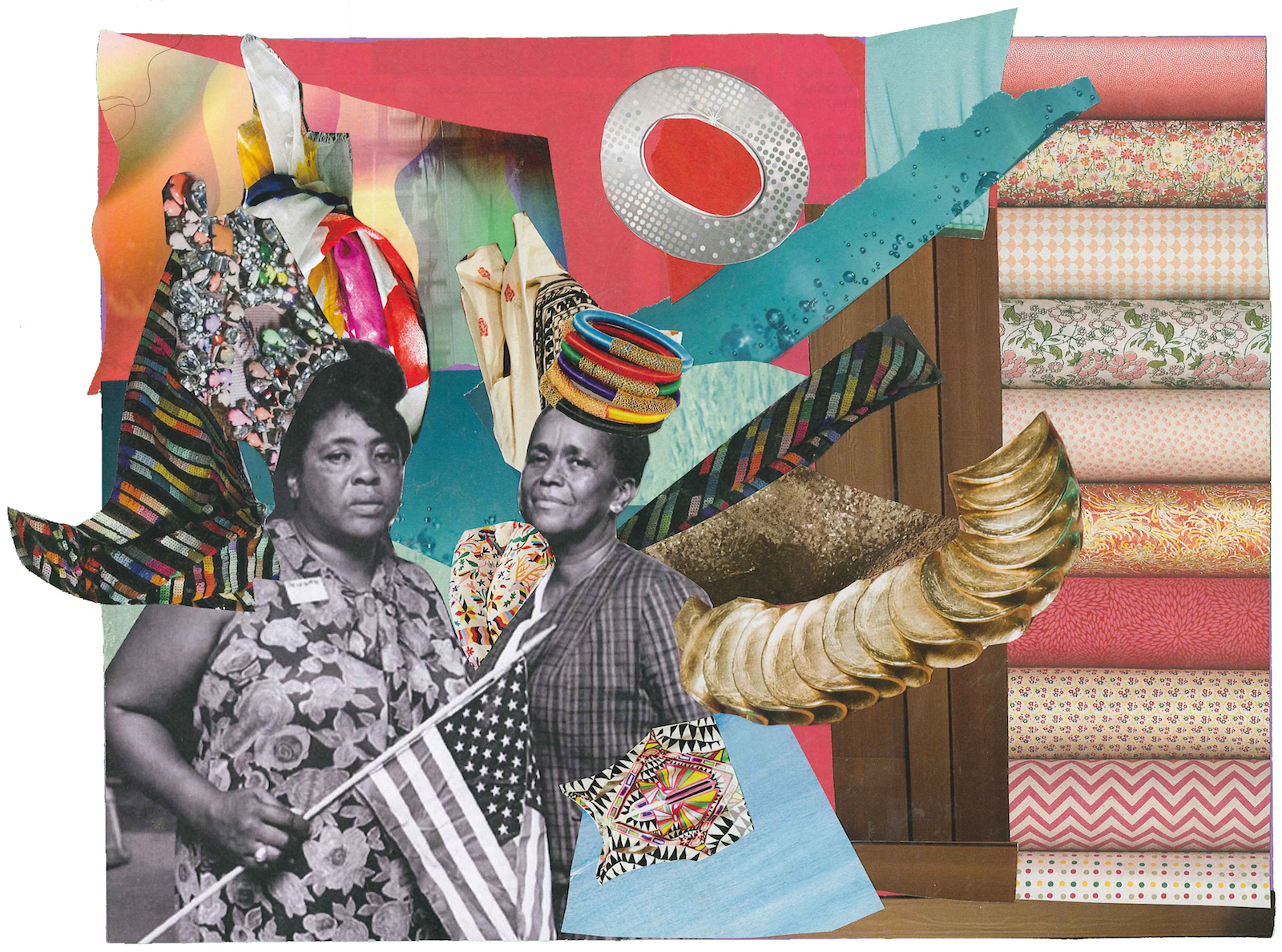

Art provides a powerful historical archive through which we can see our lost environmental past. In 1915, the artist Romare Bearden left the South at the age of four; decades later, he rendered evocative depictions of the southern natural world. His paintings and collages capture the lush bounty of city gardens and the women who made them grow. Cut off from the South by a northern, urban life for six decades, by the 1970s, he seemed mystified by the vegetables and flowers that sprouted from his canvases. At first, he contained them in baskets or plots, but they eventually overgrew the human figures in his work.

I’ve looked so long for Maudell Sleet because she did make a difference. She produced the beauty that inspired art.

Fred Romare Howard Bearden, born on September 2, 1911, to Bessye and Howard Bearden in Charlotte, North Carolina, became one of the foremost American artists of the twentieth century. From a middle-class African American family, Bearden lived for his first four years in a compound of family houses in downtown Charlotte with his parents, grandmother, and great-grandparents Henry and Rosa Kennedy. The Kennedys’ Victorian home, to which Bearden returned in his imagination fifty years later, had a wrap-around porch and a garden full of flowers. At the Kennedys’ grocery store beside the house, Bearden watched urban gardeners arrive laden with produce. The Kennedys had lived there happily and successfully since 1877, but after white supremacy campaigns in the elections of 1898 and 1900, Charlotte began to strictly segregate and disenfranchise African Americans.

9. Eating Dirt, Searching Archives: Excavations from a Texas Woman

by Endia L. Hayes

Land of the sweet, never sour, Sugar Land, Texas, offers a surburban alternative outside the expanding Houston area. The city has gone by many names. In 1838, two years into the Republic of Texas’s victory over the Republic of Mexico, what is now Sugar Land was named the Oakland Plantation. Stephen F. Austin (the “Father of Texas”) gave land to businessman and administrator Samuel May Williams as payment for his work providing land grants as incentives to bring white settlers to the new republic. In 1853, Williams sold the plantation to his brothers, Nathaniel and Matthew Williams. Together, they combined the plantation with adjoining lands and renamed it Sugar Land. The late 1800s brought a new nickname to Sugar Land among the city’s convict laborers: “Hell Hole on the Brazos.” Sugar Land’s infrastructure expanded in the decades following the end of convict leasing in 1912, resulting in the erasure of the city’s histories of Black and Indigenous removal. The city’s wealth—held almost exclusively by its white business owners, former plantation owners, and political elites—grew thanks to sugar tours, school field trips to the humid banks of the Brazos River, and the wealth generated by sugar production. These legacies of violence, swallowed by the earth and long buried, were unearthed in 2018 when developers disturbed the dirt underneath the city.

There are many Black afterlives that have yet to be unearthed.

10. Hunting Memories of the Grass Things: An Indigenous Reflection on Bison in Louisiana

by Jeffrey U. Darensbourg

A few months ago, longing for an ancestral experience I’ve never had, I went on a bison hunt to Costco, where it is possible to buy rectangular packets of mushy ground meat. While there, I spied another shrink-wrapped package in the prepared foods section, this one containing pastrami beef ribs from a company in Austin. They caught me, those ribs. They reminded me of something deep in the collective past of my people in Louisiana, and of what we have lost.

The last chance for an anecdote has passed. Not only have the wild bison of Louisiana walked on but pieces of us walked on with them.

I’m an enrolled member of the Atakapa-Ishak Nation of Southwest Louisiana and Southeast Texas. Ishak, “the Human Beings,” is what we have traditionally called ourselves and how I refer to us. From the Colonial Era until now some have referred to us as Atakapa, a name that outsiders have given, one that means “man eater.” That sort of flesh isn’t sold at Costco—and, in any case, the term likely refers not to cannibalism but to the specter of enslavement by the Ishak that other Indigenous Nations of the Gulf South feared. Like many Indigenous People of Louisiana, my heritage is ethnically mixed. Our ancestors in the distant past called themselves Ishak because their ancestors did, and so do we.