What follows are the essays that our readers turned to the most in 2022—or in the case of the Sonic South Issue from last winter, what they spun on repeat. Regina N. Bradley, that issue’s guest editor (and a co-editor of the journal), brought together a collection of essays that “showcase[d] the sonic South as vibrant while cracking out truths like arthritic joints.”

It was a year of “cracking out truths” and looking for ways to mend broken systems, broken things, and broken selves. In the Abolition Issue, we envisioned a world without policing, prisons, or other forms of punishment. In the Crafted Issue, we pursued means to repair fractures, or to create whole new possibilities. In the Sanctuary Issue, we sought solace, refuge, or as Atlanta artist Dawn Boyd Williams simply put it, “a place where you can sigh.” And in the Sonic Issue, we made noise, we sat silently, and we danced and danced.

Bradley concludes in her introduction to the Sonic South, “Some of those truths, quiet as many would like them to remain, find ways to stomp and sing and gurgle themselves into existence.” We thank our writers and artists for helping sound those out over the past year. And we thank you, our readers, for reading and listening.

1. Malik Rahim’s Black Radical Environmentalism

by Joshua B. Guild, photographs by Jeff Whetstone

It would be easy to dismiss Rahim’s dream as tragically naïve or unrealistic. But the long history of Black struggle invites, even requires, this kind of fantastical imagining.

In the sweltering summer of 2010, as thousands of barrels of crude oil from the Deepwater Horizon oil rig explosion that April gushed daily into the Gulf of Mexico, sixty-two-year-old Malik Rahim took an unusual course of action. He got on his bike. The New Orleans native and lifelong organizer announced his intention to cycle from southeast Louisiana to Washington, DC, “stopping at state capitals, universities and community centers along the way,” to call attention to the needs of Louisiana’s fragile coastline. Described in a press release as a “novice cyclist but a veteran activist,” Rahim planned to complete his journey in just over two months, inviting “all interested parties to join him on his ride, particularly those with the Green Party and other environmental affiliations.” “Now more than ever, our wetlands need to be rebuilt,” Rahim declared. “We need help!”

2. Art & Alchemy

North Carolina Repair Professionals

by Katy Clune and Julia Gartell

Mending and maintaining objects is ultimately an act and expression of care for the thing itself—for the customer, for the environment.

Drive through any town, anywhere, and among the essential food stores and gas stations there are repair shops. “There will always be a need for somebody to repair broken stuff,” said ceramics restorer Lenore Guston. “Because we’re humans, we’re breaking stuff all the time.” Over the last year and a half, with the support of an Archie Green Fellowship from the Library of Congress’s American Folklife Center, we set out to discover the current state of repair industries in North Carolina. Often, when something is fixed, the repair itself is invisible—the chip is polished away, the paint perfectly matched. We wanted to know about the stewards of our belongings, the folks who know how to reverse our mistakes and erase the imprint of time passing. This set of twenty interviews, conducted between September 2020 and July 2021, opens the workshop door and steps behind the customer counter to reveal the artistry, satisfaction, and expressions of care behind repair.

3. Louisiana Trail Riders

by Jeremiah Ariaz

Though I had been to many festivals and parades in my eight years in Louisiana, this was a distinctly different affair.

While riding my motorcycle on Louisiana Highway 77 in 2014, I encountered a group of nearly fifty people on horseback. They commanded the narrow, two-lane road that runs along Bayou Grosse Tete, and I pulled off to the side for them to pass. As they rode by, I retrieved my camera from the saddlebag of my bike and took a few photographs. People waved, hollered, lifted drinks, and tilted hats, giving themselves to the camera. A gentleman I’d later meet, Henry, motioned to me from the end of the procession, encouraging me to join them. I was immediately aware of the rare opportunity I had been granted, turned my motorcycle around, and began to follow, occasionally pulling ahead to photograph the loose procession of riders.

4. Reading Foxfire

by Jessica Wilkerson

When detached from a complex past, Foxfire contributes to the construction of an imagined and static white Appalachia.

I grew up in a house full of books, three of which belonged to my dad. They were his wellworn Bible; How I Made a Million Dollars in Mail Order, and You Can Too; and The Foxfire Book. Published in 1972, The Foxfire Book carried the reader into the mountains of North Georgia, near the East Tennessee hills where my parents grew up and where I was raised. In 1966, thirty or so tenth-grade students from Rabun County, Georgia (population about eight thousand), set out to document the lives of elders in their community. They did so as part of a school project their teacher Eliot Wigginton started. He helped them edit and publish the interviews in the Foxfire Magazine, and it became a local hit. Wigginton had connections to a New York publishing house that found the project appealing and published The Foxfire Book, the first in a series of twelve that quickly became a bestseller, selling more than two million copies over a decade. It has also been adapted into a Broadway production and television movie.

5. Mémwa Nwa

Agency, Sound, and Women in AfroCreole Louisiana Folk Music

by Denise Frazier and Sultana Isham

Sound is a portal to blood memories of the forgotten, and the ones who were in bondage used the power of sound and text to illustrate their experiences of loss and love.

In Pulitzer Prize–winning poet and writer Natasha Trethewey’s Memorial Drive: A Daughter’s Memoir, Trethewey writes poignantly of her reaction to Funkadelic’s Maggot Brain album cover while remembering the brutal murder of her mother at the hands of an ex-husband. “So this stays with me: a woman with an afro like the one my mother wore in the early 1970s, buried up to her neck in the dirt, head flung back, her mouth wide open in what looks to be a scream of agony,” she writes. “Her thoughts—everything I couldn’t know—locked in her head until she began to unleash them in the last words she wrote, and in that final scream, before her death, would render her as bone white, as beyond help, as the woman’s head on the album’s flip side.” The personal heartache of remembering brutality, as seen in Trethewey’s memoir, as well as in Jesmyn Ward’s Men We Reaped, and, earlier, in Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God, illustrates how women have navigated and continue to endure the economic, social, and colonial imaginaries of the Gulf South. How do we exhume the stories and narratives that are “locked” away, as Tretheway poignantly indicates? Despite the challenges inherent in recovering memory, there is value in how African-descended women were and are remembered and revered, especially during historical periods of enslavement, when African-descended bodies, spirits, and general humanity were most compromised.

6. Flood City, USA

Anthropocene Landscapes in the Gulf South

by Keith McCall

Industry provided the prosperity that built the subdivision, industry drew out the groundwater and sank the neighborhood, and industry funded an ecological restoration project on the ruins of the neighborhood.

The city of Baytown, Texas, home to the sprawling ExxonMobil refinery and across the ship channel from the San Jacinto Monument, sits on a peninsula jutting southwest into the upper reaches of Galveston Bay. It once housed the picturesque Brownwood subdivision, where, beginning in the 1950s, executives of Humble Oil lived midcentury dreams of postwar affluence in a suburban paradise. Those dreams washed away in the 1960s and 1970s as the peninsula sank after repeated and increasingly severe flooding. Though residents of the Brownwood subdivision banded together and installed flood-avoidance infrastructure, the neighborhood continued to sink. In 1983, when Hurricane Alicia hit the area and once again devastated the subdivision, the federal government and the city used section 1362 of the National Flood Insurance Act to buy out the property owners. By way of a series of fortuitous events, the former Brownwood subdivision is now home to the Baytown Nature Center, a constructed wetlands area featuring tidal marshes, seabirds, and alligators.

7. “We’re Not Just Shooting the Breeze”

Marching Bands and Black Masculinity in New Orleans

by Matt Sakakeeny

We head off into the night, the kids holding their instruments straight, their knees interlocked in step, a model of discipline and swagger.

Summer is the season when the new recruits arrive. They are kids, eight or nine years old, and most have never touched an instrument. On June 20, 2019, I crowd into an air-conditioned classroom with about thirty of them, sitting on industrial carpet, facing forward. LeBron Joseph stands in front of the whiteboard writing out the notes of rhythm exercises.

8. Something That Must Be Faced

Carrie Mae Weems and the Architecture of Colonization in the “Louisiana Project”

by Claire Raymond and Jacqueline Taylor

She observes these architectures from the implied perspective of a ghost, her gaze a critique of longstanding structures of racism.

In her series (Untitled) Kitchen Table (1990), photographer Carrie Mae Weems explores and questions perceived notions of racial and racially gendered identity, using the familiar, everyday experience of a woman seated at a domestic kitchen table. Alternating between images of herself alone and with a male lover, child, or with other women, she figures the kitchen table as an architectural space within which to present ideas about tradition, family, monogamy, and relationships. The beautiful, clear-eyed, and complex images in this series established Weems as a photographer politically engaged in critiques of how power is expressed in social space. Yet, Weems has received little attention, to date, for how her photographs of architecture—including antebellum plantation houses (the Louisiana Project, 2003), classical buildings in Rome (Roaming, 2006), and dwelling structures in western Africa (Africa, 1993)—comment on racial subjectivity. In the Louisiana Project, Weems highlights the potential of buildings and landscapes to engage discourses of power, identity, gender, and race. By emphasizing architectural space, Weems’s black-and-white photographs in the Louisiana Project reveal how architectural and preservation practices emerge from and, in turn, influence cultural beliefs about identity and race.

9. Sounding the South / Souf

by Regina N. Bradley

Sound is where the South can be its most complicated and unapologetic being, where it can boast its plurality and multiple communities.

One thing I did not have on my 2020 Bingo Card was being sonically minstrelized by a white man. A friend asked me to write a short reflection about OutKast and their connection to Afrofuturism for a special issue of a fiction magazine featuring writers of color. My piece talked about the Kast’s use of sound as a tool of freedom and experimentation, whether here in the South (Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik) or out in space (ATLiens). It was the sole nonfiction piece in the issue. The magazine’s customary practice was to have a voice actor read and dramatize the pieces as complements to the print versions. The actor hired to voice the special issue—reading the stories of Black folks, Brown folks, and other writers who ain’t white—was a white man. Wayment nie. My essay started with the sentence “I’m a southern Black woman raised in the long shadow of the Civil Rights Movement.”

10. Solitary Gardens

by Ana Croegart

Letter from Jesse on March 10, 2019:

Ana,What shall we plant next? Well . . . I will say I love the pansies year-round—momma used to grow squash & peppers in these pots next to our door at these apartments where we once lived. I’ve been thinking about greens a lot—I love honeysuckle & kudzu vines, they remind me of home. But listen, you can help me with my food growing choices—my thing is wanting people to eat out of my garden.

I think about Jesse’s words as I plunge my fingers into the soil of a raised garden bed in New Orleans’ Lower Ninth Ward. The squash, peppers, and greens were harvested last month, and this morning I am finding space to plant carrot seeds between a robust patch of lemon balm and a sculptural object at the bed’s front. The sculpture is one of three in the garden, each designed by pouring mortar into molds shaped like a bed, a toilet, and a table. This “furniture” is modeled on the actual dimensions of the sole elements in the solitary confinement cell in which Jesse has lived for more than a decade, and from where he writes me letters about what he would like to plant in his garden on “the outside.” Jesse’s garden bed is one of several located in a small park tucked behind a high school, all of which are created in the standard size of a solitary confinement cell in US prisons: 6 × 9 feet. These garden beds are the first of artist and prison abolitionist jackie sumell’s Solitary Gardens outdoor social sculpture project, imagined through her twelve-year correspondence with Herman Wallace, who survived forty-one years in such conditions at Louisiana State Prison in Angola, Louisiana, until his release in 2013.

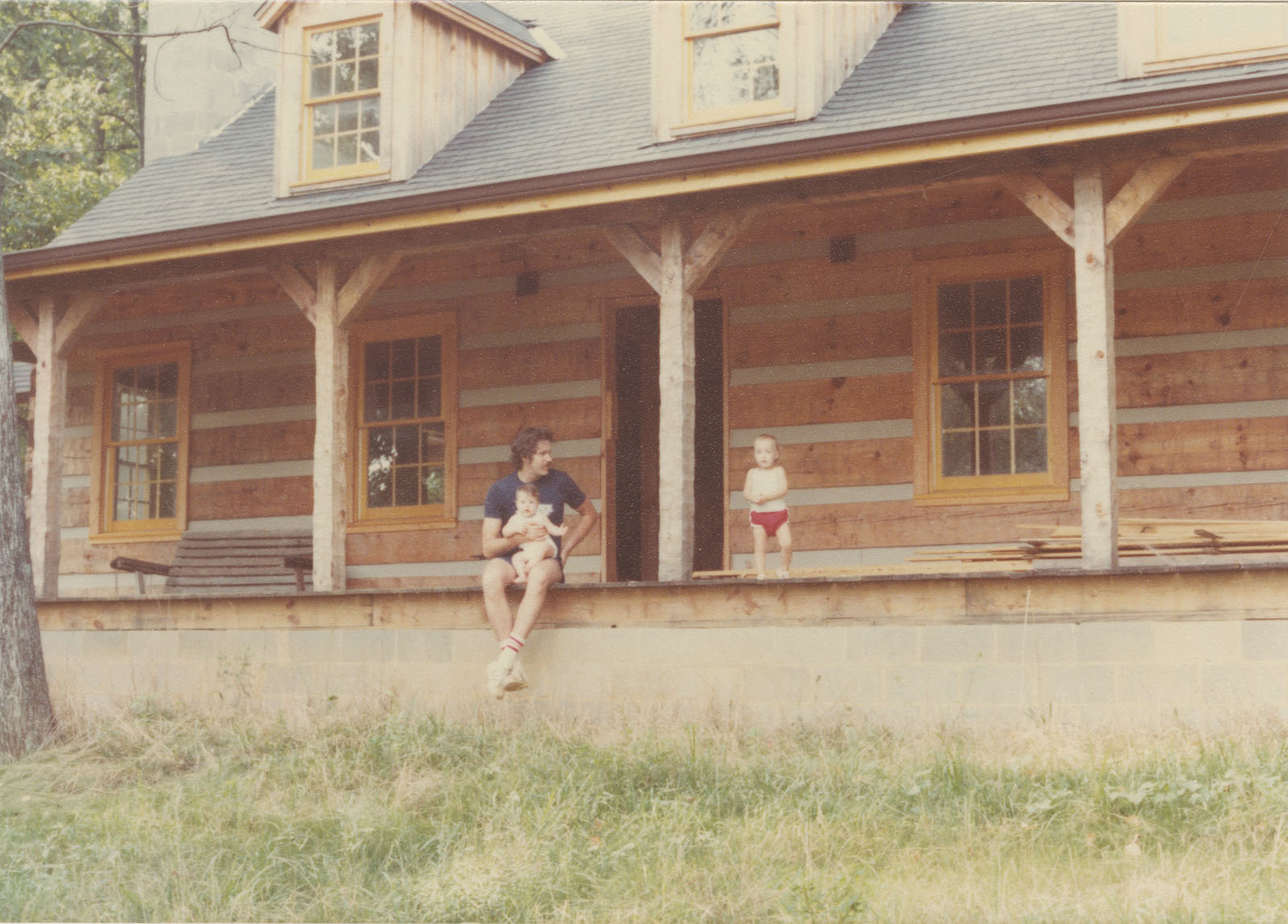

Header image by Jade Orlando from “Sounding the South/Souf.”