"The 'grain' is the body in the voice as it sings, the hand as it writes, the limb as it performs." — Roland Barthes1

Summer 1964. Downtown Charlotte, North Carolina. Jim Scancarelli, staff member at local radio and television station WBT, spots “Uncle” Frank Rayborn sitting with his banjo on a poplar-wood chair on the sidewalk of South Tryon Street. He rushes to his office to grab a tape recorder. For this banjoist is truly unique: he only has one arm. An empty shirt sleeve dangling by his left side as Rayborn’s right hand picks the strings over the banjo’s body, he leans its neck toward a pole attached to his chair, enabling him to bar chords and fret individual notes. For two hours, he picks old-time music and discusses his life and disability, interrupted occasionally by two streetside associates, “bedraggled characters smelling like alcohol,” under the false impression they are being recorded for the radio. Finished recording, Scancarelli thanks the group, deposits some change in Rayborn’s banjo case, and leaves.

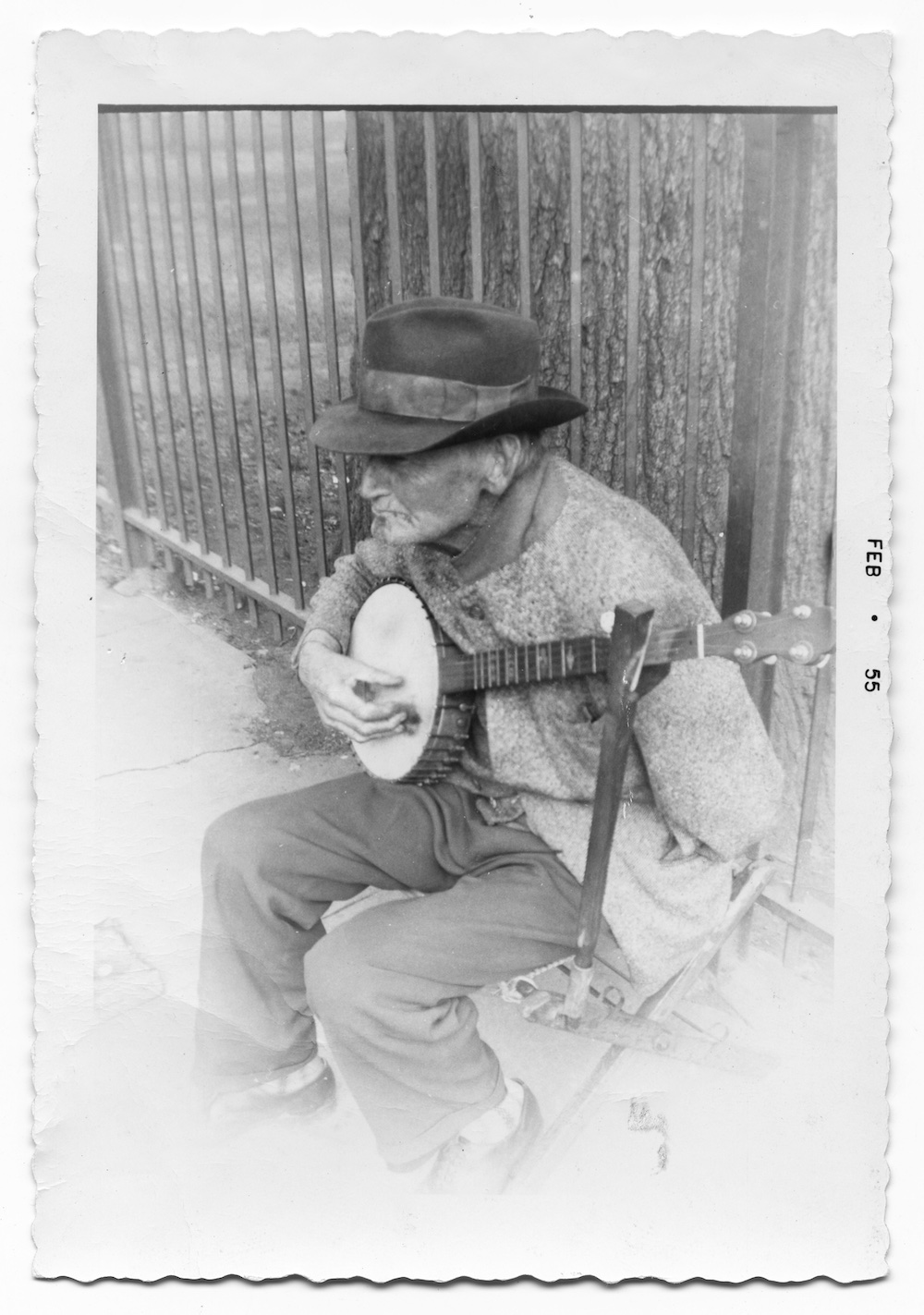

For Rayborn, the whole encounter must have felt like déjà vu. A year earlier, Phillip H. Kennedy, a young professor of Romance Studies from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill then re-tracing the footsteps of folksong collectors Cecil Sharp and Frank C. Brown, had recorded and photographed Rayborn on a muggy August afternoon at his home in the Charlotte suburb of Thomosboro. Eight years before meeting Kennedy, on a bitterly cold January day in 1955, sophomore North Carolina State University student Charles D. Webb, on a break between semesters, also noticed Rayborn busking. Like Scancarelli, Webb hurried to buy a Brownie Kodak camera from the nearest drug store and take a handful of blurry photographs before rushing to catch his bus to Asheville. Webb later recalled that, even with the cold weather, Rayborn had a “good lick.” Some five years before Webb photographed Rayborn, two reporters at the Gastonia Gazette and Charlotte News had independently interviewed and photographed Rayborn for human-interest stories for their respective newspapers.2

But who was “Uncle” Frank? Born on New Year’s Day, 1881, in the Long Creek Township near Trinity Church, ten miles out of Charlotte, Rayborn lost his arm at the age of six when a March wind blew over a tree that he and his brother were cutting. A doctor amputated his arm to save his life. At age ten, Rayborn gradually figured out how to pick the banjo with his feet, learning southern mountain music, old-time ballads, and sacred songs from his elders. He quickly overtook even his two-handed brother with his banjo prowess. “There were three things I was always good at,” Rayborn told Scancarelli, “pickin’ the banjo, pickin’ cotton, and pickin’ a chicken leg!” Rayborn also played the banjo by flipping the instrument upside down (and so reversing its string orientation) and hammering-on with his right hand. For over thirty years, though, his playing was assisted by a purpose-built chair, seemingly designed by an acquaintance who worked at the Cannon Mills textile company in Kannapolis, North Carolina. He switched to the device because he was “embarrassed” about playing with his toes. Notwithstanding Rayborn’s ingenuity and dexterity, picking the traditionally two-handed instrument was anything but easy. Five out of the thirteen verses of the traditional ballad “Naomi Wise” were enough to cause cramp in his picking arm. And age didn’t help; as he got older, he could no longer keep up with the quick fretwork of the song “Cindy.”

Rayborn claimed to have appeared over local radio programs (though not WBT) in the 1930s, even performing alongside famed country musician Bill Carlisle, and he had supposedly once won a special prize at a fiddlers’ convention performing the banjo “almost every way.” However, he never achieved substantial fame. “Expenses et it up,” he told one reporter. “I got a wife and five livin’ children … and seven grandchildren.” Despite his remarkable musical abilities, Rayborn felt life had cheated him. As he put it, accompanied by a light-hearted chuckle, the doctor who cut his arm off as a child saved his life but also “cut off [his] fortune.” By the late 1940s, Rayborn usually could be found busking near the First Presbyterian Church on Charlotte’s West Trade Street, or on North Tyron Street, near the Sears Roebuck parking lot. Four days a week his son would drive him downtown, where, weather permitting, he would pick until five in the afternoon, making up to $3 a day (and more near Christmas). Locals expressed mixed reactions: Scancarelli recalled “ladies in their finery looking down their noses in contempt” at Rayborn’s sidewalk show. One of Rayborn’s boozy curbside associates, though, thought his banjo-playing was wonderful, and that his handicap “wasn’t really a handicap at all.”

During their conversation, Rayborn bragged to Scancarelli that he was once able to haul three hundred pounds of cotton with just one arm. When Scancarelli compared him to John Henry, Rayborn proudly picked the song about the eponymous Black railroad worker right back to him, almost (dis)embodying the heroic essence of the famed steam-driving man. Explaining why he had a metal strip installed onto his banjo’s neck, the one-armed picker stated it was so he could “run up on ‘Cripple Creek’”; in other words, to allow him to more easily pick the traditional folksong and tricky banjo pickers’ showpiece. Given Rayborn’s sense of humor, one wonders whether his reference, and then subsequent performance of the song, whose title might be interpreted differently by a disabled performer and their audience, was, in fact, a joke.

To modern eyes and ears, the Rayborn that comes down to us via sparse surviving sources—in archived notepads, reminiscences, articles, photographs, tapes—might appear as the compromised and vulnerable victim of the ableist gaze. But by reading between the words, images, and sounds in the archival record, we also receive a picture of the disabled artist staring back at his onlookers. By recognizing how he flaunted his artistry—one produced by, not merely in spite of, his disability—we hear Rayborn, in the language of disability scholars, “cripping” folk music practice. In these traces of his musical and disabled life, Rayborn is both subject and agent, and entangled in the ever-shifting “ways of staring”—at and from the disabled body—that inhabit the cultural history of disability.3

Whether Ray Charles’s blindness or Hank Williams’s spina bifida occulta, the annals of southern roots music resound with “moral” tales of folk who “overcome” their disabilities to attain artistic mastery and/or commercial success. This “journey” typically parallels, and provides a convenient metaphor for, economic and social mobility: the transformation of a “dirt-poor” farmer into a show business star. Wrapped up in the class, gender, and race politics of rurality and authenticity, this patronizing, ableist “overcoming” narrative (one by no means unique to music or to the South) is familiar to disability studies scholars, and increasingly also within music studies and southern studies. But what do we know about the lived experiences of disabled southern musicians, especially lesser-known acts like Rayborn who did not “make it”? And what can their diverse experiences in southern musical culture tell us about how disability was conceived and represented in the twentieth-century South?4

Ironically, limb loss, as a disability defined culturally by bodily absence, has been conspicuously present in much southern roots music, particularly old-time music, a category of rural Appalachia-associated music often (mistakenly) coded as white, and, to a lesser extent, African American country blues. The place of limb loss in southern roots music offers insight into the juncture where disability, poverty, gender, and race meet in the South, a place where musical roots run deep, and a volatile mixture of diverse medical, socioeconomic, racial, and ecological contexts creates distinct conditions for how disability is lived and understood. Underscoring the roles of patronage, voyeurism, and agency in the lives and careers of disabled folk who captured the imaginations of folklorists, radio and record producers, and audiences likewise allows us to unpack how disability both disrupts and reinforces notions of masculinity (it appears most prominent southern roots musicians with limb differences were male), white identity (and, as I suggest later on, Black identity), and difference in southern culture. It calls us to reconsider narratives of embodiment, difference, and spectacle not at the “extremities” of southern culture and history but at their core.

The story of limb loss in southern roots music can be traced back to the legion of one-armed and one-legged musicians—beggars, military veterans, enslaved people, and many more—who labored across the antebellum South playing fiddles, pianos, and banjos as novel entertainments for curious, mostly able-bodied audiences. The harrowing volume of limb injuries that occurred during and after the Civil War marks another chapter to the story. The conflict’s new industrial modes of maiming, which intersected with high incidences of poverty, infectious disease, and inadequate medical care, forced untold thousands of Confederate soldiers (and many civilians and freed and enslaved people) to undergo all manner of amputation. Although “[d]estroyed, dilapidated, and disorganized medical records prevent historians from ever knowing how many amputations took place in the Confederacy during the Civil War,” recent scholarship indicates the unprecedented prevalence of amputation below the Mason–Dixon Line during this period.5

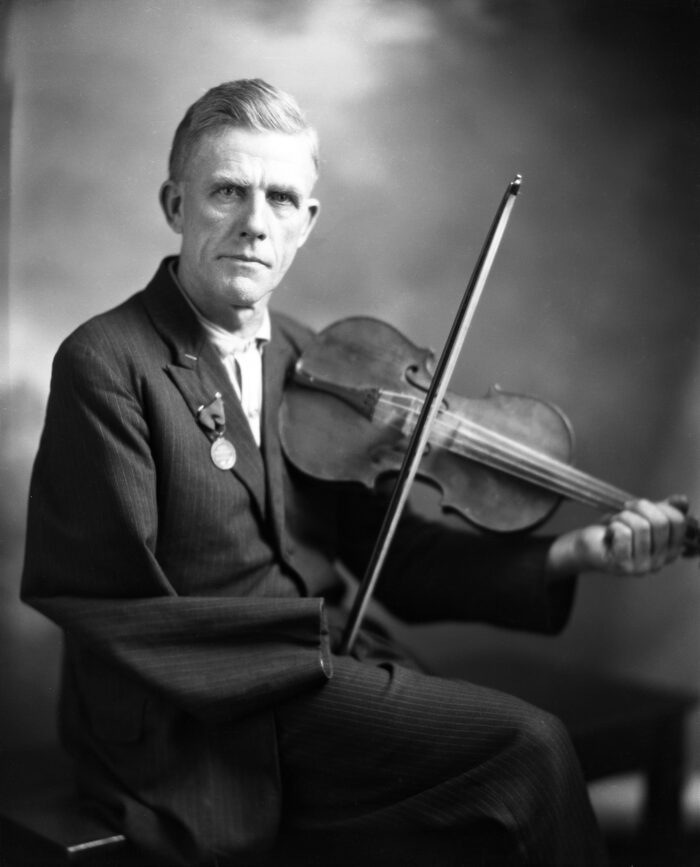

As the decades passed, Confederate veterans with limb differences became prominent figures in southern politics and culture, especially in lobbying for disability and pension benefits. Wearing their Confederate hearts on their (empty) sleeves, veterans also participated in old fiddlers’ contests. Equal parts pedagogical, theatrical, and sports-like, such competitions, populated mostly, though not exclusively, by older white male fiddlers, became important domains of southern musical culture. Often organized by self-appointed “guardians” of white southern memory, such as the United Confederate Veterans and the Daughters of the Confederacy, fiddlers’ contests presented veterans and other older southerners who played, attended, and organized them as “living monuments” to the Old South. In the early twentieth century, grizzled veteran-fiddlers became sonic mythmakers of the Old South and cultural emissaries of “Lost Cause” ideology, a set of beliefs that encouraged white southerners to manipulate and control narratives about race, slavery, the Civil War, and Reconstruction in order to uphold white supremacy.6

Veterans who performed at fiddlers’ contests lived with the visible and invisible scars, wounds, and disabilities obtained through military service. As Susan-Mary Grant writes, “amputation became the symbolic wound of the Confederate war,” as “waving the bloody stump … served to remind southerners of the sacrifices of the Civil War generation.” For Lost Cause ideologues, amputees became living, breathing (dis)embodiments of the Confederacy. Like Dixie itself, they were “defeated” and “broken” but remained courageous, dignified, uncowed, their virile southern masculinity unaffiicted. Examples of what disability studies scholars David T. Mitchell and Sharon L. Snyder term “narrative prosthesis”—the process by which disability and disabled people take on rhetorical meaning in print and visual media—can be found throughout representations of one-armed veteran fiddlers. In 1911, Confederate Veteran magazine reported that many of the “old heroes” at the unveiling of a Confederate monument in Opelika, Alabama, were “one-armed and one-legged, but a majority of them were [still] vigorous, hale, and hearty men.” Similarly, the one-armed Confederate veteran-fiddler F. S. Copeland, crowned “champion” of Alabama and Georgia in 1920, was noted for his energetic physicality.7

Playing in the face of seemingly insurmountable barriers, one-armed veterans became curiously conflicted metaphors for what Brian Craig Miller calls “Confederate incompleteness”: the South had lost, in quite a literal sense, but could still be made “whole” again. This implicit message can be read in a 1921 newspaper report of a Chattanooga contest where veteran H. F. Brock, a resident in Austin, Texas’s Old Confederate Home, who lost his arm at the battle of Pleasantdale, Louisiana, “saw[ed] out some lively music on his fiddle [i]n spite of his 81 years and only one arm.” At some fiddlers’ contests, lifelong corporeal markers of Civil War service seemingly trumped musical ability. Prizes were regularly offered to any fiddler who had lost a limb in the Civil War. With decision-making entirely subject to the whims of judges and crowds, fiddlers with missing arms may have held some “advantage” over their two-armed competitors. How can we know, for example, whether the one-armed fiddler W. M. Pritchett won first prize at an 1899 Paducah, Kentucky contest because of his musical prowess, his disability, or a mix of the two? That so many amputees entered (and won) fiddlers’ contests, though, testifies at least to the vast social impact caused by wartime amputation, effects felt throughout the South. In 1898, for example, all of the elected officers of the UCV’s Camp McMillan in Chipley, Florida, were one-armed.8

There was something deeply ironic about the glorification of disembodied Confederate veteranhood at fiddlers’ contests, given that such events were intended, in part, to erase aspects of the South’s past. In 1910, the one-armed fiddler and veteran Reuben Phares, who lost his right arm from a gunshot wound at the Battle of Mansfield in 1864, was given special treatment at a Dallas contest where speakers also lectured on “states’ rights” and the South’s supposed identity as a white nation. Phares’s limb loss unintentionally becomes allegorical for a “dismembered” southern history that Confederate memory workers were busily etching into history textbooks, monuments, and public policy near the turn of the twentieth century, and the attendant “amputation” of Black perspectives from that history.9

If fiddlers’ contests helped reinforce a “white disability (Confederate) nationalism” around one-armed veterans, they also exhibited amputees as “freaks” who performed bodily wonders. One one-armed fiddler H. F. Brock, for example, was described as an “unusual and pathetic sight.” Focus typically rested squarely on the inventive adaptions amputees deployed to play their instruments. Brock “skillfully held the bow between his knees, and with his left arm manipulate[d] his fiddle.” Fiddlers’ contests presented disabled performance as spectacle: after all, it was typically one-armed rather than one-legged veterans who dominated the contest stage. One-armed fiddlers were both invisible and hypervisible. Their thoughts and feelings were rarely documented in contest reports (unlike their able-bodied competitors who were regularly quoted on everything from Civil War history to women’s suffrage); their “remarkable” bodies, meanwhile, were singularly noteworthy parts of the entertainment. In this respect, southern fiddlers’ contests perhaps should be thought about in the context of the American “freak show,” an entertainment tradition that exhibited and exploited disabled bodies for public consumption. As well as being viewed as the nation’s own “freak show,” the South produced and enjoyed an array of travelling freak shows. Fiddle contest promoters and audiences, therefore, were likely intimately familiar and comfortable with this kind of entertainment. Although one-armed white male fiddlers were allowed far more autonomy and respect than the average freak show performer, not least because of their honored status as Confederate veterans, freak shows laid the groundwork for contest audiences to view disability with grotesque wonder.10

Reuben Phares, like Brock, fastened the bow between his legs to use the fiddle “like other performers do the bow.” After an exhibition of this skill at a fiddlers’ contest in Branham, Texas, in 1900, Phares received an outpouring of charity from the crowd:

some big-hearted individual in the gallery threw a dollar at him, and this was the signal for a downpour of coins, such as probably never overtook the old man before. This was accompanied by shouts from all over the house of “Old man, go buy you a watch, and buy you a good one.”

As condescending as those shouts may sound to modern sensibilities, in some ways fiddlers’ contests genuinely helped economically vulnerable disabled southerners. Individual state-produced Confederate veterans’ pension schemes, veterans’ homes, and a small number of artificial limb programs in states like Mississippi were typically inaccessible and shabby when compared to federally orchestrated welfare channels available to Union veterans. Given the obstacles many disabled Confederate veterans faced as civilians sourcing work, housing, and healthcare, including those who, as Jonathan S. Jones charts, became opioid addicts, it seems likely that some amputees looked to fiddling as an alternative income source, even a means of reclaiming a lost sense of masculinity. In 1904, Phares filed for a Confederate pension with the state of Texas, claiming he owned no property or source of income; perhaps most damaging for his sense of manhood, Phares survived only by living on his wife’s family farm. In an accompanying affidavit, Phares’ physician confirmed to the pension authorities that their patient was, indeed, missing an arm, and highlighted other conditions, including cataracts in both eyes. They concluded that Phares’s health was bad for someone aged only sixty. By 1910, Phares was living as an “inmate” in the same Austin-based Confederate veterans’ home where the one-armed fiddler H. F. Brock also resided. For audience members, fiddlers’ contests were sites of charity, pity, and degrading comedy; for Phares, the contest stage was a route to much-needed financial relief.11

It was not only disabled veterans who benefited from contest charity. In 1926, Ford Motor Company agents spent $305.51 “tak[ing] care of the Old Time Fiddlers,” including providing the one-armed Westmoreland, Tennessee fiddler Marshall Claiborne a barber’s cut, a new suit of clothes, and treatment at a Detroit hospital. The Ford agents’ patronage of one-armed fiddlers is particularly ironic. In 1923, Henry Ford, perhaps conscious that industrial accidents in his factories actually created amputees, publicly hailed his automated Model-T assembly line as “enabling” its “less than able-bodied” workers: in a Ford factory, the automobile mogul proudly claimed, 670 operations could be filled by legless men, 2,637 by one-legged men, 715 by one-armed men, and two by armless men.12

Fiddlers’ contests, apparently like Ford’s factories, offered diverse opportunities for veterans with all kinds of limb differences. The one-armed Oxford, Georgia veteran-fiddler Colonel A. V. Poole both performed at contests and acted as master of ceremonies. In 1899, Texan fiddler Henry C. Gilliland, who famously recorded the “first” old-time record for a commercial phonograph company in 1922, applied for a Confederate pension in his adopted home of Oklahoma, claiming that periostitis of the leg and hip joint, muscular atrophy, and the shortening of a limb caused by “exposure and heavy duty guarding the gulf coast of Texas” during the war, meant he could no longer conduct manual labor. It was after Gilliland’s claim was rejected because he owned too much land (even though he claimed the land was arid) that he wholeheartedly began to engage in contest culture, even presiding over the influential Old Fiddlers’ Association of Texas, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. Without Gilliland’s wartime injuries, and the ableist postwar society in which he lived, the “birth” of early country music may have taken a different route.13

Like Gilliland, who helped inaugurate old time music’s phonographic era, Emory Martin, born in 1916 to a sharecropping family near Bon Aqua Junction in Hickman County, Tennessee, hitched his ride to stardom on another development in sound technology: radio. At age seven, Martin began to play the banjo on the floor with his stump, feet, and then teeth before getting his “break” as a teenager at a Nashville talent contest. The white musician soon was performing with Sid Harkreader and “Uncle” Dave Macon at the Grand Ole Opry and recording with Kitty Wells. In the 1940s and 1950s, he was a regular performer on the Louisville, Kentucky–based radio show Renfro Valley Barn Dance. Unlike one-armed veteran-fiddlers with acquired amputations, Martin’s six-inch left-arm stump (or “stub”) was a congenital anomaly. That Martin became successful with what would have been considered a “birth defect” is significant. This was a period rife with eugenic theories and derogatory depictions of poor white southerners, particularly Appalachians, as genetically deformed “hillbillies.” Perhaps some audiences, especially those from outside the South, viewed Martin’s disability as a signifier for mountain people’s supposedly isolated, “inbred,” and impure characteristics, but neither Martin nor Renfro producer John Lair let such ideas germinate. Martin dressed smartly in suits rather than the stereotypical yokel costumes that other barn dance performers wore. It was a source of pride for the Renfro Valley promotional machine when Martin married and had children with the able-bodied and musically talented fiddler and fellow Renfro star Wanda “Linda Lou” Martin. Although Emory Martin was always identified by his disability (“the one-armed banjo player”; “radio’s only one-armed banjo player”; “America’s greatest one-armed banjo player”; “the world’s only one-armed banjo player”), other descriptors of his talents (“wizard”; “champion”; “king”) highlighted his mastery of his instrument, or, to borrow from music scholar Matthew J. Jones, his “crip virtuosity.” Martin’s brilliance was accentuated even more, one contemporary reviewer claimed, because the banjo was “one of the most difficult string instruments to play in the world.”14

Martin nurtured his public image as a disabled genius. It was he who insisted on being introduced as a “one-armed” performer because he “knew from experience” that advertising the fact would draw crowds to their stage shows. As Martin later recalled in a newspaper interview, with a dose of pragmatism, “I had to be seen, I had enough sense to know that.” Keeping in mind childhood experiences when strangers travelled to the Martin family home to see how he played but quickly became uninterested once they had witnessed the spectacle of his disabled performance, Martin set upon enhancing the complexity of what he played. Disability, for Martin, was about difference, not deficit. As a teenager, he worked hard to master particularly dastardly tunes which showcased his stub-, toe- and teeth-picking abilities. The song “When You and I Were Young Maggie,” Martin recalled, was “quite a hard tune to play” but he “didn’t want it to look too easy, I wanted to use every string there was on the banjo.” Five frets was about the limits of Martin’s dexterity when playing with his feet. While there were plenty southern folksongs that only required two frets, Martin “didn’t think that was hard enough” and “wanted to make it more complicated than that.” It was a deeply complex learning process, with his disability profoundly shaping his musical approach:

My style was completely different … I had to make a note and get away from there or it’d muffie the whole thing. If it was instrumental, I played the lead. If it was a song, I played the melody. The only chord I could make was a bar chord straight across.

The typical open-tuning of the five-string banjo (where a chord is struck without holding down any frets) made all this possible. Martin did learn to play the guitar, but only by tuning it like a banjo. It was Martin’s ability to “produce a purity of tone seldom achieved by any banjo player” with “no mechanical devices of any kind” that at least one reviewer saw as unique. By contrast, one of Martin’s contemporaries, Luther Caldwell, a one-armed Kansas City, Missouri fiddler, performed with an elaborate system of mechanical pedals in order to bow the fiddle. Reportedly designed by a group of mechanics at a Mizzou plant, Caldwell’s machinery won him an appearance in Popular Mechanics magazine and a spot on Ted Mack’s NBC television show Amateur Hour in 1953. In Caldwell’s case, his prosthesis became the audience’s fixation; for Martin, though, everything rested on his bodily abilities.15

In producer John Lair’s hands, Martin’s life story became primarily an inspirational tale for able-bodied people. In a 1946 broadcast, Lair presented Martin’s indefatigable determination as totemic of the plucky American character:

Now watch this boy play the five-string banjo with his teeth, and listen to every note just as perfect as if he had 15 or 20 fingers on the strings … You take a fellow with that much determination, a boy who’s had one arm all of his life and is determined to learn to play the banjo, a very hard instrument to master, and a fellow who can do it that way, you must have to take your hats off to the good old American spirit that keeps a boy like [that] on the job until he got clear to the top in his particular profession.

Lair’s comments are interesting for two reasons. First, his use of a national trope (the underdog-done-good) moves away from the fiddlers’ contest identification of the overcoming narrative of disability with southernness; instead, disability is framed within a story of national reconciliation, ironically right at the cusp of a new wave of sectional divisions about to erupt in the postwar Civil Rights era. Secondly, it is telling that Lair doesn’t present Martin as a “regular supercrip” (someone with a disability who gains attention for “mundane accomplishments”). Rather, Martin more closely resembles what disability scholar Amit Kama calls the “glorified supercrip” (someone with a disability who accomplishes “feats that even non-disabled persons rarely attempt”). For a southerner to embody the “American spirit,” Lair implies, they not only had to work as hard as a one-armed person, they had to be professionally successful too.16

Radio, as an aural medium, made the representation of disabled talent challenging for producers hoping to portray supercrip narratives. Some Renfro broadcasts were recorded with live crowds, and the cast regularly toured as a revue show, but audiences typically first heard disabled musicians over their radio sets. Lair understood that listeners would be curious to see the one-armed picker in action. “Maybe you’ve believed it, maybe you didn’t,” the wily promoter told listeners during a 1959 broadcast, with one eye clearly on an upcoming Renfro tour, “you have to see it to believe it.” An advertisement for a Renfro road show in Florida, similarly, beckoned listeners who had heard Martin on air and “wondered if he really picks the banjo and if so, just how he hangs on to it.” The guitarist Chet Akins, who performed alongside Martin during a short stint at Knoxville’s WNOX, later wrote in his autobiography that “freaks” like Emory Martin “drew people to the roadshows.” Other musicians used kinder words. Jo Midkiff referred to Martin as a “showstopper” who could draw multiple encores. Country singer Kitty Wells, meanwhile, who had performed with Martin early in his career, recalled that he was “a great guy, and he was a good banjo player, too, in spite of what some people might think.”17

Like the “inspiration porn” of modern-day TV talent shows, Martin’s supercrip identity was framed predominantly by and for able-bodied people. For his part, Martin spun more or less the same story as Lair. Lair even relinquished his characteristically aggressive control over his artists’ money-making activities in Martin’s case, allowing him to sell a pamphlet detailing his inspirational life story, written by his mother. Like Rayborn, Martin adopted audience-favorite “John Henry” as a signature song, one that symbolically captured his own dogged determinism. His reasons for playing up to the supercrip character were fairly obvious: Renfro Valley provided Martin a steady job and wage (even if he, like other cast members, believed Lair took more than his fair share in the station’s earnings). Performing also offered him some agency in his working life, including the auditioning of (able-bodied) bandmates. Martin’s comments on quitting show business in the late 1950s illustrate the limitations people with limb differences faced in the postwar South. “I sold my banjo and quit,” he later recalled. “But it didn’t take me long to find out that people weren’t going to hire me, so I went to work for myself.” Martin opened a service station right next door to the Renfro Valley barn. As he told a reporter in 1994, reflecting on his artistic and business accomplishments, “if you think it through before you do it, you’ll be surprised at your success.”18 Linda Lou Martin’s short 1991 biography of her husband, One Armed Banjo Player: Early Years of Country Music with Emory Martin, pieced together from conversations with Emory and his mother Maud, begins with Maud describing the moment when her mother and doctor informed her that her newborn child only had one arm. The text is a rare glimpse into the life and emotions of a disabled person and their loved ones in early-twentieth-century Tennessee. Maud recalls, perhaps with rose-tinted glasses, how she resolved then and there to treat Emory “as any normal child,” to ensure he was not “pitied or petted.” The extra effort Maud made to keep him “clean and neat,” so he would never feel embarrassed, suggests how able-bodied female caregivers of her generation navigated ableist expectations. She recalls watching her seven-year-old son fretting his father’s banjo for the first time with his “piece of left arm,” tuning it by turning its pegs with his teeth; her pride in how “he did this all by himself”; her later satisfaction that he would go on to “get out and earn a good, honest living for himself and be admired by thousands of friends throughout the country”; her initial reservations about Emory competing in a talent contest (“it seemed useless”); and, conversely, Emory’s father’s constant encouragement of his musical ambition. Linda Lou’s authorship means One Armed Banjo Player cannot be described as a disability memoir or “autosomatography,” but we can nevertheless hear Emory’s voice in the text, including his difficulty in finding a way to play the fiddle one-handed, and his decision to adapt fiddle tunes he learned from his uncle for the banjo; or his experiences as a sixteen-year-old, out on the road with Sid Harkreader, where he was already marketed as a “novelty” performer but was grateful for the relatively generous wage of $2.50 a night (“pretty good pay during the Depression,” he remembered, when field work reaped only $1 a day).19

Martin was one of many disabled performers on barn dance radio who titillated live audiences in sometimes degrading circumstances, from Ray Mears, an armless steel-guitarist who played alongside Martin at WNOX, to Little Moses, the “human lodestone” who entertained audiences with his ability to make it difficult for anyone to pick him up (a labor which left him “black and blue from people tugging at him”). Although typically understood as the innocent, organic soil from which grew country music as we recognize it today, barn dance radio, like fiddlers’ contests, was entangled in the long, dark tradition of the American “freak show.” Martin and his disabled contemporaries’ varied experiences demand that the history of disability in country music, much like its shameful record of misogyny and racism, be more critically reconsidered.20

It is equally vital that we consider where these histories intersect: the white Emory Martin, after all, held fond memories of performing alongside Buck Martin, a white comedian who performed in blackface. Indeed, the sources often lead us back to the “cavalier way that Black people’s pain,” as literary and disability studies scholar Dennis Tyler astutely writes, “was often misconstrued as a fount of entertainment.” During the “race record” boom of the 1920s, many record labels tastelessly and offensively exploited Black blues and gospel singers’ blindness. Columbia Records’ (white) promotional team did much the same for the Black songster Joshua Barnes “Peg Leg” Howell. “When ‘Peg Leg’ Howell lost his leg,” one 1926 press release joked, “the world gained a great singer of blues. The loss of a leg never bothered ‘Peg Leg’ as far as chasing around after blues is concerned. He sure catches them and then stomps all over them.” Like his one-armed white counterparts, though, the Atlanta-based Howell, who lost his leg in a gun fight with his brother-in-law in 1916, used music to express his own selfhood as a disabled musician. Howell’s performance of the steadfast “Walkin’ Blues” (1929), in particular, aligns him within a Black tradition of “disability humor” that Africana studies scholar Darryl A. Smith traces back to the period of chattel slavery.21

While the (debatable) “success” stories of Howell and Emory Martin tell us a little about the intersection of disability, power, and music in the South, it is necessary to recognize the existence and mastery of countless other artists with limb loss who never quite “made it”: those “nobodies” like Frank Rayborn who struggled to sustain a financially sustaining career beyond collecting spare change; or the white John Henry Burgess, of Gastonia, North Carolina, a left-handed musician known as “Cigar” because he had a plug in his mouth to block the strings on his banjo, who, according to Rayborn, was “a music makin’ man in his time” before he died in 1949 from diabetes; or an unnamed one-legged Black banjoist from the 1860s about whom we know almost nothing, aside from their image preserved in a single photograph. Even those who “made it” could quickly fall victim to a cutthroat, prejudiced music industry. When “Peg Leg” Howell was “rediscovered” in 1963 by young white enthusiasts on the blues “revival” scene, he was then entirely legless and living in poverty in Atlanta. The once one-legged bluesman had sustained Columbia’s interest for only so long. By 1952, he had lost his second leg due to diabetes-related complications. Howell’s medical history resonates with what public health bodies today call the “epidemic” of amputations among Black communities in the South. Largely because of diabetes and shamefully persistent racial inequalities in healthcare, Black people remain disproportionately likely to undergo second amputations.22

We must cherish what small details survive of figures like Rayborn, Phares, Martin, and Howell, and be mindful of how the study and preservation of southern music history has prevented their stories from being told in any depth, or, more importantly, in their own words. A fascinating, yet also frustratingly brief, detail in the Rayborn archive, for example, is that he listened to other one-armed banjoists, including Martin and fellow Carolinian John Henry Burgess. It is also essential that historians (especially able-bodied ones like myself) are conscious of how well-intentioned attempts to “reclaim” disabled musicians’ lives risk reinscribing the same ableist “stare” under which they lived their whole lives. By unearthing, amplifying, and demystifying these artists’ long-forgotten music and firsthand testimonies, we can better understand their historical contexts, while still respecting their personhood and artistry. But it is a delicate balance. Disabled southern musicians, in short, should not become historical “oddities” any more than they should have been considered “freaks” in their own time. Living, breathing human beings, these hard-working, talented, and even flawed folk used their musical platforms as (albeit limited) avenues for self-expression to entertain, amaze, shock, and delight their audiences, running them (and us), as Rayborn would have put it, “up on Cripple Creek.”23

This essay was published in the Disability issue (vol. 29, no. 1: Spring 2023).

Simon Buck, PhD, is a writer, historian, and musician. His first monograph, on old age and music in the US South, is under contract with the University of Illinois Press. He is employed at the University of Edinburgh (UK) on research projects concerning the intersection of British slavery, healthcare, and university education in Edinburgh.Header image: Sketch of Uncle Frank Rayborn, by Jim Scancarelli. Reprinted with permission of Jim Scancarelli.

Header image: Sketch of Uncle Frank Rayborn, by Jim Scancarelli. Reprinted with permission of Jim Scancarelli.

NOTES

- Roland Barthes, “The Grain of the Voice,” in Image-Music-Text (New York: Hill and Wang, 1977), 188.

- I have drawn freely from the following sources for my account of these specific encounters, and subsequent biographic detail about Frank Rayborn’s life: “Uncle Frank Rayborn,” Reels 1 and 2, AFS 14088a and 14088b, in “Jim Scancarelli recordings of fiddle and banjo music,” American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, Washington, DC; Lewis M. Stern, Jim Scancarelli: Fiddler, Banjo Player and Gasoline Alley Cartoonist (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2022), 50–51; untitled photographs of Frank Rayborn, August 1963, Image Folder 15–17, “1963–1965 and undated,” in Philip H. Kennedy Collection #20328, Southern Folklife Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; photographs, “Charles D Webb collection of photographs of Uncle Frank Rayborn,” 1955, (AFC 2012/012), American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, Washington, DC; “Hoyle Wins Music Meet,” Charlotte News, April 24, 1947, 6; E. P. Holmes, “Banjo Artist Makes Music, Merry or Sad, with One Arm,” Gastonia Gazette, May 13, 1950, 21.

- For this essay, including its title, I draw on a wealth of “crip theory,” in which disability scholars and disabled activists reclaim and reimagine the socially derogatory term “cripple.” For disability and music, see Joseph N. Straus, Extraordinary Measures: Disability in Music (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011); George McKay, Shakin’ All Over: Popular Music and Disability (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2013). For “ways of staring,” see Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, “Ways of Staring,” Journal of Visual Culture 5, no. 2 (August 1, 2006): 173–192.

- William Cheng, “Staging Overcoming: Narratives of Disability and Meritocracy in Reality Singing Competitions,” Journal of the Society for American Music 11, no. 2 (May 2017): 184–214, 2.

- Brian Craig Miller, Empty Sleeves: Amputation in the Civil War South (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2015), 11.

- For two excellent essays on limb loss and music from a Union perspective, see Devin Burke, “‘Good Bye, Old Arm’: The Domestication of Veterans’ Disabilities in Civil War Era Popular Songs,” and Michael Accinno, “Disabled Union Veterans and the Performance of Martial Begging,” both in The Oxford Handbook of Music and Disability Studies, ed. Blake Howe, Stephanie Jensen-Moulton, Neil Lerner, and Joseph Straus (Oxford University Press, 2015), 403–422, 423–446; R. B. Rosenburg, Living Monuments: Confederate Soldiers’ Homes in the New South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001). For Confederate memory workers, see Karen L. Cox, Dixie’s Daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2003); Adam H. Domby, The False Cause: Fraud, Fabrication, and White Supremacy in Confederate Memory (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2020); Gaines M. Foster, Ghosts of the Confederacy: Defeat, the Lost Cause, and the Emergence of the New South, 1865–1913 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988).

- Susan-Mary Grant, “The Lost Boys: Citizen-Soldiers, Disabled Veterans, and Confederate Nationalism in the Age of People’s War,” Journal of the Civil War Era 2, no. 2 (2012): 243; David T. Mitchell and Sharon L. Snyder, Narrative Prosthesis: Disability and the Dependencies of Discourse (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2000); Confederate Veteran 19, no. 5, May 1911, 250; Birmingham News, September 11, 1920, 2.

- Miller, Empty Sleeves, 10; Chattanooga News, October 27, 1921, 9; other novelty awards included those for “oldest fiddler” and “fiddler with the longest beard”: J. H. Lowry, “All Sorts of Fiddlers,” Honey Grove Signal [TX], February 16, 1900, 4; “Confederates Open Sessions at Biloxi,” Washington Post, June 3, 1930, 11; The Bee Earlington, June 1, 1899, 3; Confederate Veteran 6, no. 4, April 1898, 155.

- “Rebel Yell Resounds at Fair: Veterans Talk of Other Days,” Fort Worth Record and Register, October 19, 1910, 3.

- Stephen Knadler, “Opioid Storytelling: Rehabilitating a White Disability Nationalism,” Journal of American Studies 55, no. 5 (December 2021): 1098–1124; Chattanooga News, October 28, 1921, 14; Kevin S. Fontenot, “Country Music’s Confederate Grandfather,” in Country Music Annual 2001, ed. Charles K. Wolfe and James E. Akenson (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2001), 196; Erik Kline, “The Freak Show—Spotlight: Erksine Caldwell,” in Routledge Companion to Literature of the U.S. South, ed. Katharine A. Burnett, Monica Carol Miller, Todd Hagstette (Routledge, 2022). For the “fascination with southern life as a freak show,” see Eleanor Blair, “Here Comes Honey Boo Boo, Moonshiners, and Duck Dynasty: The Intersection of Popular Culture and a Southern Place,” Counterpoints 434 (2014): 132–146. For more on the “freak show,” see Rosemarie Thomson-Garland, ed., Freakery: Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body (New York University Press, 1996); John Woolf, The Wonders: Lifting the Curtain on the Freak Show, Circus and Victorian Age (London: Michael O’Mara, 2019).

- R. L. Christian, another so-called “crippled” veteran-fiddler from Austin, received the same treatment: “Old Fiddlers Contest,” Houston Daily Post, February 11, 1900, 8; Joanna Short, “Confederate Veteran Pensions, Occupation, and Men’s Retirement in the New South,” Social Science History 30, no. 1 (2006): 75–101; Jonathan S. Jones, “Opium Slavery: Civil War Veterans and Opiate Addiction,” Journal of the Civil War Era 10, no. 2 (2020): 185–212; Reuben Phares, Pension File Number 10212, February 9, 1904, in Confederate Pension Applications, 1899–1975, Texas State Library and Archives Commission, Austin, Texas; “Rebel Yell Resounds at Fair,” 3.

- Paul M. Gifford, “Henry Ford’s Dance Revival and Fiddle Contests: Myth and Reality,” Journal of the Society for American Music 4, no. 3 (August 2010): 331; Henry Ford and Samuel Crowther, My Life and Work (New York: Doubleday, Page, 1923), 108–109.

- Gene Wiggins, Fiddlin’ Georgia Crazy: Fiddlin’ John Carson, His Real World, and the World of His Songs (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1987), 48; Kevin S. Fontenot, “Country Music’s Confederate Grandfather,” 193.

- See Anthony Harkins, Hillbilly: A Cultural History of an American Icon (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005); Bristol Herald Courier [TN], February 21, 1943, 8; Troy Messenger [AL], February 14, 1944, 3; The Republic [IN], November 26, 1955, 4. For crip virtuosity, see Matthew J. Jones, “‘The Hexagrams of the Heavens, the Strings of My Guitar’: Joni Mitchell’s Crip Virtuosity,” in Joni Mitchell: New Critical Readings, ed. Ruth Charnock (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019), 21–42; Record-Citizen [OK], May 15, 1951, 5.

- Jennifer Hewlett, “Five Fingers All Martin Needs for His Five Strings,” Lexington Herald-Leader, February 6, 1994, B3, B1; Emory & Linda Martin, JL-CT-056-002, in John Lair—Renfro Valley Barn Dance Oral History Collection, Berea College Special Collections & Archives, Berea, Kentucky, https://berea.access.preservica.com/uncategorized/IO_b5a9eacf-9efa-43e3-8f3f-82e8d4202c35/; Tampa Bay Times, February 23, 1949, 15; Liner notes to Luther Caldwell, One Armed Fiddler of Boone County MO (Missouri State Old Time Fiddlers Association, MSOTFA 107, 2015).

- “Turkey in the Straw,” Emory Martin (performer) and John Lair (presenter), recording of Renfro Valley Barn Dance, June 29, 1946, WHAS, Louisville, Kentucky, JL-OR-013-07, in John Lair Papers, Berea College Special Collections & Archives, Berea, Kentucky, https://soundarchives.berea.edu/items/show/4065.

- Amit Kama, “Supercrips versus the Pitiful Handicapped: Reception of Disabling Images by Disabled Audience Members,” Communications 29, no. 4 (2010): 454; Tampa Bay Times, February 23, 1949, 15; Chet Atkins and William Neely, Country Gentleman (Chicago: H. Regnery, 1974), 144–145; Wayne & Jo Midkiff, JL-CT-058-002, in John Lair—Renfro Valley Barn Dance Oral History Collection, Berea College Special Collections & Archives, https://berea.access.preservica.com/uncategorized/IO_40c0cfe1-7a63-4da4-bb72-0853108d5379/; Jennifer Hewlett, “Country Loses Unique Banjoist,” Lexington Herald-Leader, 19 April 2006, 10.

- Emory & Linda Martin, JL-CT-056-002, in John Lair—Renfro Valley Barn Dance Oral History Collection; Michael Ann Williams, Staging Tradition: John Lair and Sarah Gertrude Knott (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2006), 89; in the previously referenced oral history, Wayne Midkiff recalls auditioning for Martin in a restaurant in June 1946, earning a job as fiddler in Jack Holden and the Georgia Boys; Wayne W. Daniel, “Emory & Linda Lou Martin, Sweethearts of Renfro Valley,” Old Time Country, Fall 1992, 10–11; “Renfro Valley News,” Nashville Tennessean, October 1, 1966, 9; Hewlett, “Five Fingers,” B3.

- All quotes in this section can be found in Linda Lou Martin, One Armed Banjo Player: Early Years of Country Music with Emory Martin (Berea: Kentucke Imprints, 1991). For autosomatographies, see G. Thomas Couser, Signifying Bodies: Disability in Contemporary Life Writing (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2009).

- Atkins and Neely, Country Gentleman, 145.

- Dennis Tyler, Disabilities of the Color Line: Redressing Antiblackness from Slavery to the Present (New York University Press, 2022), 112; The Latest Blues by Columbia Race Stars (New York: Columbia Phonograph Company, 1926), 13; Darryl A. Smith, “Handi-/Cappin’ Slaves and Laughter by the Dozens: Divine Dismemberment and Disability Humor in the US,” Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies 7, no. 3 (2013): 289–304.

- “A black banjo player with a wooden leg. Photograph, ca. 1865 (?),” Wellcome Collection, Public Domain; Mark Holmes, “Banjo Artist Makes Music,” 21; “An Interview with Peg Leg Howell,” liner notes to Peg Leg Howell, The Legendary Peg Leg Howell (Testament T-204, 1964), LP record; Lizzie Presser, “The Black American Amputation Epidemic,” ProPublica, May 19, 2020, https://features.propublica.org/diabetes-amputations/black-american-amputation-epidemic.

- Holmes, “Banjo Artist Makes Music,” 21.