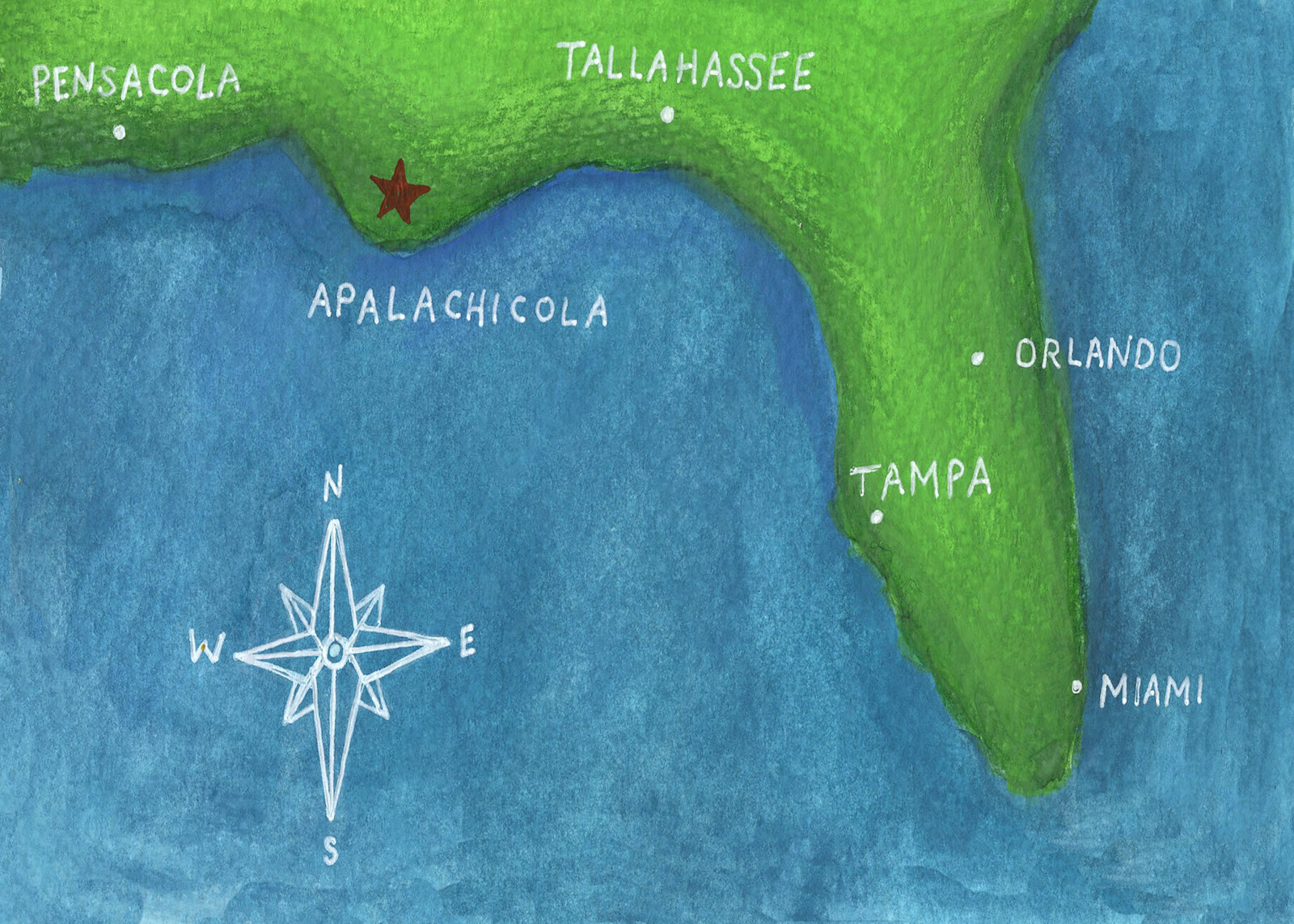

I walk into Boss Oyster Bar in Apalachicola, the little port town at the bottom of the famous river. Boss cuts to the chase, dispensing with ruffles and flourishes, a seafood shack of the old school, a bit scruffy, wind-whipped, with some young salt sitting there with a bushel of bivalves shucking as though the sunrise depended on it. You can sit on the porch over the water, gazing on the source of your food, and order your oysters fried, steamed, baked, or breaded, in stew, in a taco, in a po’ boy, festooned with jalapeños, feta, or bacon. You can exercise such options, but why would you not want them as Nature intended—perfectly raw, untouched by anything more than a spritz of fresh lemon or a dot of red sauce? They lie on their shells, silvery, voluptuous, and big as your fist, a little sweet and faintly briny, a taste as sunny as an afternoon in the warm, green shallows of the Gulf.

I know, I know: raw. Think how long it took Americans to entertain the idea of sushi. Even now, some people will stare at the most perfect slice of line-caught yellowfin and call it “bait.” It’s rare to get an egg yolk in a Caesar salad, and, God knows, some people are terrified of ceviche. And there’s no denying that four or five people die every year from eating raw oysters. The offending bacterium, Vibrio vulnificus, can make you very sick, especially if you have liver problems or a compromised immune system. V. vulnificus likes warm water, salty water. I eat my raw oysters when the Gulf is cool, winter and early spring. And I pray for fresh water, for the flow from the north. Everyone in Apalachicola prays for the river to send the revivifying water down from the mountains.

The Apalachicola country is a fiesta of living things: 1,300 species of plants, forty species of amphibians, eighty species of reptiles, the highest density of amphibians and reptiles north of Mexico. Unusual animals such as the West Indian Manatee and the Indiana Bat turn up, along with fifty other kinds of mammals, 131 flavors of fish, 300 kinds of birds, and some of the rarest flora on earth: Torreya trees, Florida yews, Apalachicola rosemary, which only grows in Liberty County, and the Carolina Grass of Parnassus with its gauzy, white, star-shaped flower.

Unlike peninsular Florida, which made a habit of lying underwater for much of its geological history, the north central and northwestern parts of Florida remained higher and drier, with rivers still connected to the North American mainland. Species that would seem to belong in the sharper temperatures of the Appalachians—gopherwood, mountain laurel, Dusky Salamanders—thrive in the steephead streams and ravines. These species moved south during the last Ice Age and never left. The lower Apalachicola is wet prairie and marsh punctuated by pine flatwoods, and along the banks and in the swamps, cypresses as tall as cathedral spires.

The river is a long, slow banquet, a many-coursed feast.

Much of the land around the Apalachicola is in public hands; and from the Jackson River to the west, south to the Gulf, and east to Tate’s Hell Swamp, it’s as close to unspoiled as you’ll find in the overstuffed strip-malled and highway-scarred rest of Florida. Aside from the spectacular biodiversity, the ethereal quiet, and the startling beauty of a hundred iterations of green, the river is a long, slow banquet, a many-coursed feast. I’m not being metaphorical; I’m really talking about food. Bream and catfish up near the Georgia state line, tupelo honey hived on the floodplains east of Wewahitchka, opulent white, brown, and pink shrimp, fat blue crabs, dainty scallops, and fish—pompano, flounder, and mullet—thrive in the rich waters of the bay. Most significantly, gloriously, the oysters. Always oysters. Here is an article of Florida faith: There is no oyster like an Apalachicola Bay oyster. Not in this fallen world. There are other good oysters (really good oysters) from Louisiana, Galway, the Pacific Northwest, Prince Edward Island, Maine, Virginia, Denmark. But they’re not Apalachicola Bay oysters. The bay terroir (if a terroir can be underwater) yields a truly wild, Nature-made oyster of unparalleled sweetness—buttery and fragrant.

After I down my dozen, I walk down Water Street, past a potter’s studio, a new hotel dressed up in old Apalachicola brick, and an antebellum cotton warehouse. (Before seafood and tourism, cotton was Apalachicola’s economic dynamo, coming down the river from Georgia to be loaded onto ships for the mills in England.) I pass some other oyster joints, too. There are plenty of places to get them around here: Owl Café, Hole in the Wall, Up the Creek, Caroline’s, and, six miles away in Eastpoint, Lynn’s and Red Pirate. You can find a fine oyster almost anywhere along this bit of what the incorrigible branders of Florida call “The Forgotten Coast.” When you can get a local oyster, that is.

Before the crippling droughts and Atlanta building boom of the early 1980s began troubling the harvest, Apalachicola Bay oysters were plentiful, demotic, enjoyed by rich and poor. Restaurants both posh and populist, from New Orleans to Miami, served them; country folks from Florida’s pine-scrub Panhandle counties bought them by the bushel for roasts, then paved their driveways with the shells; white-shoe lobbyists in Tallahassee wooed politicians at parties where the Crown Royal flowed and the oysters had been tonged out of the water ten or twenty at a time no more than three hours earlier. Everybody consumed Apalachicola Bay oysters like potato chips at a party, insouciantly, as if they’d always be cheap and plentiful. North Florida cooks made oyster pie and biscuits, and put oysters in the Thanksgiving dressing. Students at Florida State and Florida A&M could afford to eat at Rick’s Oyster Bar when they couldn’t afford anything else. Visitors to Tallahassee would be dragged twenty-five miles south to St. Marks to Posey’s where they’d be served a couple dozen raw with saltine crackers.

Everybody consumed Apalachicola Bay oysters like potato chips at a party, insouciantly, as if they’d always be cheap and plentiful.

Posey’s is gone now, destroyed in Hurricane Dennis. Rick’s is gone, too. Apalachicola Bay oysters are no longer an immutable fact of North Florida life, any more than a freeze in November, Democratic Party control, or the Florida State Seminoles finishing in the top ten. In a decade there may be no Apalachicola oysters. There’s not enough fresh water coming down from the north.

The ecology of Apalachicola Bay depends on the alchemy of sweet water from the river mixing with salt. The bay is protected from the often bad-tempered, sometimes oil-befouled, Gulf of Mexico by skinny barrier islands. It’s shallow and clean, an oyster-perfect elixir, a Goldilocks cocktail: not too saline, not too sweet, low in predators, high in phytoplankton and other tasty eats beloved of bivalves and crustaceans. The golden ratio for oysters is between ten and twenty-two parts per thousand. Anything above twenty-six is too salty: you get oyster drills (a sea snail which bores a hole in an oyster shell and eats it) and crown conchs. Fewer nutrients reach the oysters, oyster spat (the larvae) struggle to attach to grown oysters, and next thing you know, what was a harvest of three million pounds of oyster meat in 2011 drops to below one million the following year. In 2015, the harvest was only 520,000 pounds.

Blame the oystermen for sometimes taking too many oysters, especially ones under the legal size of three inches or more; blame the drought of 2007; but mostly, blame the red tape of the Army Corps of Engineers and the water hogs of Georgia. In 1956, the Army Corps of Engineers dammed the Chattahoochee River northeast of Atlanta, creating Lake Lanier. At the time, metro Atlanta’s population was under a million people. Now it’s pushing six million, growing like kudzu over twenty-eight counties of urban, suburban, and exurban development, using Lanier’s water for their showers, cooking, golf courses, and grassy lawns. That’s mostly surface water, though; downstream, farms suck water from the aquifer as well as the Flint and the Chattahoochee, drastically reducing the amount of water available downstream. Once a farm has a water permit, it can’t be revoked, and you don’t even need a permit if you take “only” 100,000 gallons a day.

By the time the fresh water limps down to the Florida border and the Apalachicola River, it’s much diminished, guaranteed to fully nourish only one species: lawyers. Florida, Georgia, and Alabama have been suing one another for nearly thirty years. In 1990, Florida and Alabama took Georgia to court for harming their downstream flow, impacting commerce and the environment. Georgia sued the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers over Lake Lanier to get more water for the mega-sprawl that is metro Atlanta. Come 2013, Florida lawyered up again, suing Georgia for harming endangered species such as Gulf sturgeon and assorted mollusks, hurting the oysters and the 100,000 jobs that depend on bay seafood. Georgia was unmoved. Former governor, now U.S. Secretary of Agriculture, Sonny Perdue, declared that no mollusk or oyster “deserves more water than the humans and children and babies of Atlanta.” A Special Master appointed by the U.S. Supreme Court disparaged Georgia’s water lust but found in the state’s favor. The case is back in the Supreme Court, which may rule once and for all in 2018.

Meanwhile, the oystermen, the fishermen, the shrimpers, crab-trappers, and everyone else who works the waterfront in the little towns of Eastpoint, Carrabelle, and Apalachicola, watch their livelihoods wash out, their incomes plummet, their way of life critically threatened. Many of them are the third, fourth, even fifth generation to make their living on the water. With farmed oysters, imported shrimp, and cheap frozen fish flown in from the four corners of the earth piled in the supermarket refrigerator cases, the oyster folk of Apalachicola Bay are as threatened as the Florida panther. They are the last in the United States to harvest oysters the old way, by hand, hauling them up from the bay floor with long tongs, some of the last hunter-gatherers of the twenty-first century.

The Apalachicola begins 430 miles north of the Florida state line, in the Blue Ridge, where the Chattahoochee rises out of the base of Jacks Knob Mountain. The Flint bubbles up in the Atlanta suburbs, flowing under the runways at Hartsfield-Jackson Airport, sticking its head back aboveground in western Georgia, moseying through Montezuma, Albany, and Bainbridge, disappearing into Lake Seminole, a reservoir created in 1946 when the Army Corps of Engineers built the Jim Woodruff Dam. The Apalachicola emerges from the confluence, a long, luxurious curl through tall bluffs, marshes bracketed with bullrushes, meandering south 106 miles and opening like a great green fan into the Gulf of Mexico.

Seen from the bank or the side of a skiff, the river looks the color of weak coffee. From high above, as the falcon—or the satellite—sees it, the Apalachicola is veiled in emerald.

Seen from the bank or the side of a skiff, the river looks the color of weak coffee. From high above, as the falcon—or the satellite—sees it, the Apalachicola is veiled in emerald. That gauzy green cloud is chlorophyll, nourishment for the plants and animals. For millennia, the river has fed all the living things within its realm: black bears, gray bats, Chipola slabshell mussels, bald cypress trees, the mound-builders who flourished 2,500 years ago and built a capital west of the Apalachicola at Turtle Harbor, the seventeenth-century Spanish Franciscans looking to establish missions on the high ground, the Seminoles resisting Andrew Jackson’s bloody incursions into their land, slaves escaping the plantations of Georgia, and eight generations of my Cracker kinfolk.

As a child, I spent parts of the summer at St. Teresa Beach, a few miles east of Apalachicola. Tallahassee people call it “the Coast,” as if there was just the one. St. Teresa was an unglamourous “colony” of old cottages, named for Teresa Hopkins, granddaughter of Florida’s last territorial governor. Nobody knows quite how the place later acquired the “saint” prefix, maybe because of its proximity to so many other saints—George, Vincent, James, Joseph—along the Gulf.

We’d ride over to Eastpoint or Carrabelle to buy shrimp off the boats when they came in; we’d take the Boston Whaler out toward Alligator Point when low tide revealed the spits, walking carefully in the seagrass, picking up scallops. Some mornings we’d wake up to find the uncles and older cousins cleaning a mess of mullet they’d caught the night before.

Mullet’s an underrated critter, associated with an egregious hairstyle, subject to being lobbed on the beach by liquored-up good ol’ boys and girls vying to see who can chuck a dead fish farthest, dismissed as a trash food enjoyed by rubes and hayseeds. It’s true that most species of Mullidae or Mugilidae are best suited to be bait. But black mullet, Mugil cephalus (also called grey mullet and striped mullet, just to be confusing), has a deeper flavor than mackerel and is exquisite smoked, broiled with lemon, or, best of all, fried fresh, served with hushpuppies and cheese grits. She-mullet caught in November or December may yield a bonus delicacy: red roe. In our house, we steam it a bit in a pan, then fry it in butter. Mullet caviar, rich as custard. Delice de Franklin County, Florida. If what you find inside your fish is white, not saffron yellow, be advised: that’s not roe. That’s milt, mullet sperm. Some people like it. I give it to the cat.

Mullet’s an underrated critter, associated with an egregious hairstyle, subject to being lobbed on the beach by liquored-up good ol’ boys and girls vying to see who can chuck a dead fish farthest, dismissed as a trash food enjoyed by rubes and hayseeds.

I ate the other end of the river, too: bream mostly, sometimes trout or catfish. My grandfather used to take me fishing south of Woodruff Dam. We’d rise two hours before dawn and put in at Neal Landing. The sky would change from steel gray to hibiscus pink as we ate our breakfast on the water: Vienna sausages out of the can and scrambled egg sandwiches my grandmother got up at 2:30 AM to make. We baited our hooks with wigglers and waited with our cane poles in the cool silence. If the fish didn’t bite within a couple of hours, we’d move on to another creek, another room in the Apalachicola’s labyrinthine mansion. There were pools of green lily pads and pink lilies whose unattached stems hung down in lapis-blue water. Fawns would come cautiously to the bank to take a drink, and sometimes a water moccasin leered from a branch, eyes hard and glittering. Once I saw a big fish, a fish the size of a park bench, bony-backboned, flat-snouted, armored like a samurai. My grandfather took a look and steadily steered the boat away. “A sturgeon,” he said.

That night, while we ate the bream we’d caught with black-eyed peas and lemon pie for dessert, my grandfather told how he’d once seen a sturgeon in the Apalachicola near Prospect Bluff. He was fishing, sitting in a thin little skiff, and there was this creature down in the water. “I thought it was a big old catfish,” he said. “He had whiskers. But there never was a catfish twelve feet long. Then that fish commenced to swimming south. Next thing I knew, he was in front of me, rearing up like a rocket. When he hit the water, he made a wave that ’bout sent me into the drink.”

Gulf sturgeon are an ancient species, older than Florida, reaching back 225 million years. They spawn near the dam in fresh water, then migrate to brinier water in the bay come autumn. They can weigh as much as 1,200 pounds and live to be forty or fifty years old. Sometimes they appear to attack, roaring up out of the water, breaking boat windshields, knocking people overboard. It’s almost certainly not intentional, though it’s sometimes deadly. In 2015, a Gulf sturgeon on the Suwannee River leapt into a boat, striking a five-year-old child and killing her. No one’s sure why sturgeon jump. It could be to compensate for low levels of oxygen in the water or to flush out their gills. Frank Parauka, a biologist with the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, told National Geographic, “This fish is a living dinosaur,” and defended the sturgeon as “a really docile fish, easily exploited.”

Dan Tonsmeire turns the boat upriver. He’s the Apalachicola Riverkeeper, charged with advocating for the wild things of this intricate environment, protecting the integrity of the river, and trying to educate everyone from federal judges to developers to members of Congress and ordinary citizens about the importance of fresh water to the health of the whole basin. We’re entering less briny water, cypresses on the bank joined by river birch, water oaks, and palms. Osprey duck down in their shaggy, tire-sized tree-top nests, while a snowy egret takes off from the bank, light as a dandelion seed, disappearing into an aquamarine sky. A few yards in front of the boat, something I don’t quite see splashes off the bank into the water. The wild critters of Florida’s greatest river are feeling shy this sharp March morning. I don’t blame them. Their world has become unstable, the precise dance of light, soil, and water growing uneven, out of joint.

“Animals, plants, it’s all interdependent,” says Dan. He reminds me it’s not just the oysters imperiled by the lack of fresh water flow, it’s the whole shebang: “The river, the bay, the fisheries of the eastern Gulf, the floodplain; it’s a complex ecosystem.”

We’ve come to see the Ogeechee tupelos in bloom. These are the famous trees which (with the cooperation of the bees) give us the famous honey. William Bartram, the naturalist and explorer of the southeastern United States before it was the United States, is said to have “discovered” the tupelo in the 1770s during his travels along the Ogeechee River in southeastern Georgia. Of course, Native people had known the tupelo for millennia. They named it. Tupelo is a sort of contraction of the Creek words for “tree” and “swamp.” Bartram made a drawing of one, its roots rippling like the hair of a pre-Raphaelite lady, spiraling down into the water. Species of tupelo grow in China, the Himalayas, Mexico, Borneo, and Panama, but this tupelo, Nyssa ogeche, the white tupelo, belongs mostly to Georgia and Florida. The honey, the glorious golden honey made from its nectar, belongs to an even smaller area: the Apalachicola Basin.

I eat tupelo honey almost every day. But I’m lucky. A long-time Wakulla County bee man uses my family land at Smith Creek for his hives. He pays the rent in cases of bright honey, unprocessed, unadulterated. The old folks used to say it would cure what ails you. Lately, though, there’s not as much honey, and not as much of it is pure tupelo. Sometimes, other flowers have got mixed in—gallberry, palmetto, and clover. It’s still good, but lacks that rosewater scent and complex, peppery kick. If the oyster is the taste of the bay, tupelo is the taste of the Apalachicola River.

It’s really a place of rivers, streams, sloughs, and creeks, so many it looks like veins in a body.

Florida markets itself as one big beach, white sand and turquoise sea, maybe punctuated with a theme park or ten. But look at a map: it’s really a place of rivers, streams, sloughs, and creeks, so many it looks like veins in a body. It’s a miracle there’s any ground to stand on. Florida is a scrape of soil on an eggshell layer of limestone perched on top of ancient waters. The interconnected rivers made our history, our ecology. Yet the Army Corps of Engineers, the dredge- and-dam-happy federal behemoth still stuck in the era of barge traffic, ignore how the three rivers, from the foothills of the Smoky Mountains, the surrounding streams, the marshes, the basin, the estuary, and the near-shore Gulf down to Tampa Bay, are botanically, biologically, hydrologically, and geologically intertwined.

“River systems are complicated,” says Dan Tonsmeire. “The Corps doesn’t like complicated. They like straight lines and 90-degree corners, blocks, and squares.” The Corps also doesn’t like floods. Along with developers, governors, and the Chamber of Commerce, the Corps likes water to behave itself in an orderly manner. That’s why there’s a great big dike around Lake Okeechobee. That’s why New Orleans has levees (not that either of those Corps projects have worked particularly well over time). But the tupelos can’t flourish without some flooding; they want to get their feet wet. The bad news is a U.S. Geological Survey study has found that the forests in the Apalachicola Basin are becoming significantly drier—and drier forests mean fewer tupelos. The number of Ogeechee tupelo trees has declined by 44 percent since 1976. Old dredging projects have cut some of the trees off from their fresh water sources. Bees have suffered from widespread pesticide use. Upstream, endlessly replicating suburbs and shopping centers suck water the tupelos need from Lake Lanier, and Georgia farmers like to irrigate their fields. Lawns beat oysters. Cotton and peanuts trump tupelos.

Still, just around the bend of the river, there they are, Ogeechee tupelos, chartreuse leaves and pearl gray bark. Looking at them, you can see why we used to think trees were spirits. The tupelos look like dancing dryads. Some of the branches gesture downward toward the water’s surface, some reach skyward as though they’re archaic priestesses with arms up imploring the gods. The tupelos are covered in flowers that resemble tiny satellites, space-age spikes of tree frog green sticking out all over. One pound of tupelo honey takes 60,000 bees sucking the nectar out of two million tupelo blossoms. The flowers are just now beginning to open. Soon the bees will get to work collecting the nectar, storing it in their bodies and bringing it back out again as honey—a miracle, a transubstantiation of the swamp.

Dan and I ride back to Apalachicola on water calm as a birdbath. The river is paradisal: the sun is shining, the air is fragrant, herons look at us then turn away. Soon spider lilies will bloom, filling the banks with white petals. Down in the delta, we meet a couple of guys who assume we’ve been fishing. “Y’all get anything good?” one says. “I got me some six pound cats!”

“Let’s go eat some oysters,” says the other one.

You’d never think this place is in crisis. In 2012, the bay’s oyster fishery collapsed completely. The states of Georgia and Florida bickered over who was at fault—a tropical storm, the drought, the Corps, oystermen so worried that the bp oil spill would penetrate Apalachicola Bay that they scraped up every oyster that had graduated from spat stage. In any case, there were no oysters. And the bay was worryingly salty, as salty as the open sea. In subsequent years, the flow has increased—a little. The oyster bars began to come back. But it’s not what it was. Five hundred oystermen used to work the bay. Now the number is fewer than one hundred.

Dan reminds me that it’s about more than preserving a piece of quaint old Florida, or helping impoverished oystermen, or hanging onto a food beloved of gourmands. It’s about the whole ecosystem. Take out a foundational species and the eco-edifice falls apart. Oysters aren’t just tasty, they’re vital. They clean the bay, filtering twenty to fifty gallons of water a day, eating nasty algae before it can spread its oxygen-consuming poison. If the bay gets too salty for oysters, it’ll get too dirty for other marine animals. Fish kills will become common. The algae will rule.

Oysters aren’t just tasty, they’re vital.

“You lose the oysters, you lose the water quality,” Dan says. “It’s not just the ecosystem, it’s the community, too.” I stop at 13 Mile Seafood on my way back to Tallahassee. They’ve got a few oysters, last of the spring. The man behind the counter says they’re a little briny. I don’t care. I buy a bag, plus a pound of shiny fat pink shrimp to take home and boil. The Ward family, four generations of fishermen and women, own 13 Mile and run their own boats in the Gulf. I wonder what will happen if the fresh water flow from the north slows to nothing again. It could be the end of wild oysters. In Wakulla County, to the east of Apalachicola, they’re farming oysters, growing them in black plastic baskets to protect them from predators. Will Apalachicola become another pastel Florida “resort town,” not a real place with a working waterfront but a piece of ersatzery like Seaside, pretty and utterly fake, a playpen for the rich? Florida is adept at destroying organic communities and replacing them with Disneyfied developments with rules about what color you can paint your front door.

Meanwhile, the natural world does what it has since the beginning of time: try to adapt. The tupelos bloom and the oysters grow as the sun glints off the surface of the miraculous bay.

Fresh or Fried: A Southern Cultures Seafood Reader

Twelve fish(ish) tales from the archives (with accompaniments). Read the whole platter here.

This essay first appeared in the Coastal Food issue (vol. 24, no. 1: Fall 2018).

Diane Roberts is an eighth-generation Floridian, educated in Florida and England, and currently Professor of Creative Writing at Florida State University. She is the author of four books, most recently Dream State, a historical memoir of Florida, and Tribal: College Football and the Secret Heart of America. A journalist and broadcaster, her work has appeared on NPR and the BBC, and in the New York Times, Guardian, Oxford American, and Tampa Bay Times (among other places). She lives in Tallahassee.

Illustrations by Kristin Solecki