In 1942, Ms. Ella Watson of Washington, DC, spent her summer nights in the halls of the nation’s capital, where she had been working for twenty-six years. The government charwoman went to work at 5:30 p.m. in federal buildings, cleaning floors, toilets, and such, then heading home by 2:30 a.m. On one of these nights, she found herself entertaining a conversation with Gordon Parks, who had recently come to DC from the Midwest. The young, self-taught fashion photographer came to the capital to work with the Farm Security Administration and the team of photographers who documented American life from the outskirts and the underside. His mission was to expose discrimination and bigotry with his camera. He’d been discussing these matters with his director for weeks, but on this night, the director sent him over to Watson. He pointed, “Go have a talk with her … see what she has to say about life and things.”

He was a stranger, but she told him some of her story anyway: familial loss and love, strong faith. The portrait that came of this conversation was dignified, and honored Watson’s presence: her work as a laborer, her resilience as a second-class citizen in a landscape of inequality. However, when Parks followed her outside into the movements of her daily life and the spirit of her surroundings, he shifted to a new register of seeing. Rather than fixate his camera on the bigotry Black communities faced in Washington, DC, Parks used his lens to show how Watson, her family, her neighborhoods, and her church saw, supported, and affirmed each other.1

Walking with Ella Watson during that visit to DC, Parks photographed Black communal life in the Logan Circle neighborhood. He documented the inside of grocery stores. He caught children running through sprinklers and looking out over developing public housing campuses. But he spent the most time inside. He posed Watson in her apartment overlooking streetcars packed to the brim or sitting by the open door in her kitchen and catching a breeze while holding her grandkids. He made many photos of Watson reading the Bible to them and sitting by her home altar with her adopted granddaughter. Statuettes of saints, candlesticks, flowers, and oils adorned her vanity, and rosary beads hung down from the top of the mirror, framing her children’s reflections. Thick, laced cloth drapes the wood where her Bible rests at the center of the altar, open to the middle and flanked by two milky elephants. In one photograph, it is Watson who Parks frames in the mirror, a profile image rather than the steady, direct gaze she offers the camera for the iconic portrait for which they are both known: Washington, DC Government Charwoman. In the mirror, she gently bows her head, her glasses sturdy on the bridge of her nose. Her brow and housecoat catch the light, making Watson glow like the cloth, the icons, and the nimbus circling Jesus in the image that hangs next to the vanity. If the people in the streetcars beyond the window could see inside, they might look up at her image like tourists riding past stained glass on a chapel.

Watson’s descendants would remember her fondly for her faith. As her great-great-granddaughter told historian Deborah Willis in 2018, the children had never seen their great-grandmother at work or heard her speak of the photographs Parks took. They remembered brushing her hair before she said prayers on weeknights, and admiring the way she dressed in her best on Sundays. “She lived according to her faith and did not sway from it … she prayed every morning as well as every night and would instill in her family to be giving, kind, and forgiving.” The icon she remembers isn’t the figure we see in American Gothic, but the woman reflected in the mirror at the altar. And there were others. Watson was a devout Christian, and a member of the St. Martin’s Spiritual Center. In addition to the photographs of her altar, Parks photographed the church: the people, the rituals, and the sanctuary. While Watson’s images powerfully reflect the contours of one woman’s day-to-day life in the city—where she worked, where she lived—these other photographs of the church explore faith as a collective act. They show us the mutual relationship of care that exists between the community that a woman like Watson pours into and the way they pour back into her. They show us how a sense of spirit emerges in solitude, in collectivity, and both within and beyond the walls of the sanctuary.2

The St. Martin’s Spiritual Center was founded by Reverend Vondell Gassaway in 1928, and the preacher led the congregation until his death in the sixties, as Colleen McDannell writes in Picturing Faith: Photography and the Great Depression. The center was part of a broader spiritual church movement among Black Americans. Mother Leafy Anderson and Mother Catherine Seal cultivated Spiritual (or Spiritualist) churches in New Orleans, and Spiritual churches cropped up in Great Migration cities across the country where southern Black migrants established new roots throughout the early-mid-twentieth century. Spiritual church members’ religious practices reflected their diverse, diasporic backgrounds, as well as their involvement in the life of their communities. In one photograph of the sanctuary, Parks positions himself at the back of the center aisle, behind rows of women sporting their summer Sunday best: floral dresses pair with sun hats with ribbons or lace. A boy turns to look directly at the camera, and behind him, other youth fill the choir stands behind their music director and church leaders. They’re framed by statues similar to the kind Watson has on her altar at home, but here, Saint Mary stands almost as tall as the young people. Their choir robes are graduation gowns, each member wearing a cap and tassel.3

Values of religious and social education blend through intergenerational community, as well as through staging and performance. The goal of the Spiritualist church movement in the model of Anderson and Seal was to acknowledge the multidimensional nature of people—as religion scholar Margarita Simon Guillory writes—and they used the churches to “address the political and spiritual dimensions of individuals,” especially Black people disenfranchised during Jim Crow and the Great Depression. In New Orleans, as in Washington, DC, and other cities, housing and employment inequality, segregation, and racial violence fractured everyday Black life. But in the sanctuary here, the beam crossing above all reads “God is Love.” If “God is Love,” the ministry is to love Black people. Every act of worship that happens in that space, then, can be considered a technique of loving.4

From what is visible in the photographs, the symbols and icons in the sanctuary read almost exclusively Protestant and Roman Catholic. In practice, Spiritualists drew on Pentecostal, African, and Indigenous rituals of worship, emphasizing healing and transference, vision and prophecy. As religion scholar Stephen C. Wehmeyer writes, “The strong sacramental elements in Church worship—the proliferation of Saints’ statues, candles, and icons; the use of blessed oils and incenses; the powerful presence of women in the Church hierarchy—[led] many non-members to identify the Churches with ‘Voodoo,’ ‘Hoodoo,’ or ‘Conjure-work.’” But at its most basic premise, to conjure is to bring something into being; to devise new experience, sensation, and place through the material and immaterial world, and through the body. A Spiritualist practice shows how conjuring and Christian traditions intertwine in Black southern worship.5

One photograph’s caption reads As in Moses’ Time, Members of the St. Martin’s Spiritual Church Remove Their Shoes during the Annual “Flower Bowl Demonstration” because during This Service They Walk on Holy Ground. Women gather behind the chairs, feet bare on the tile floor, waiting. Parks found a different angle close to the floor, sweeping down the darkened aisle with light pouring in from behind and illuminating the bottom of a woman’s foot. She is sitting down with her feet resting on the bottom of the chair in front of her, her arches curving over the beam. During the flower bowl ceremony, congregants step into a shallow pool decorated with roses and walk through its “holiness-conferring waters,” as art historian Sally M. Promey writes. When they emerge from the waters, they receive a long-stemmed rose blessed by the pastor. If she had just passed through, the seated woman might hold her feet up to dry while she watches others receive their blessings. Or, she could be waiting for her turn, lowering her feet only when it’s time to walk on holy ground.6

Watson stands in white with her arms folded in front of her. Two women are behind her, one with her leg propped and one with her hand over her heart. They wait for their turn to walk, appearing both patient and restless. Seated, a woman fans herself and looks forward—maybe toward the music director who might be leading the congregation in song while each and every person receives their blessing and gives an offering. Each person would have been blessed and prayed over by many as they circle the sanctuary to get to the pool. The end would be healing. To pray, invoke spirit, and lay on hands—all are restorative acts.7

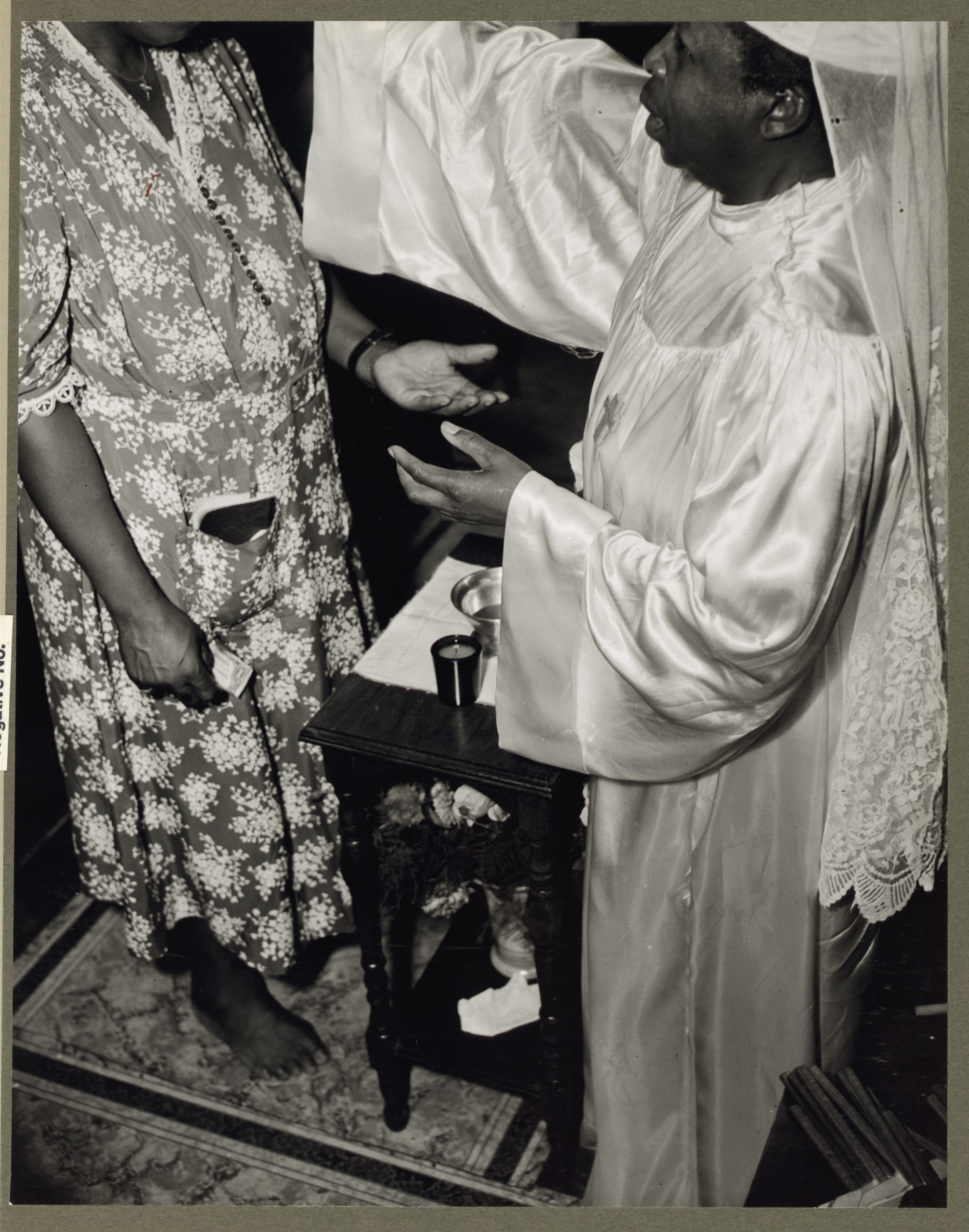

Parks photographs Reverend Clara Smith blessing Watson, and others. A woman advances to the altar with a notebook and pencil weighing down her pocket. She stands with her left hand open and extended toward Reverend Smith, her right hand holding money. Reverend Smith lays one hand on the woman’s head, praying with and over her, and begins to move the other towards the woman’s open palm, which she will take. The woman will proceed, and another will follow and take her place before the reverend and the altar: a choreography of anointing taking place in the expanse of only two floor tiles. Parks photographs the moment from an aerial angle, and he centers the gesture and the exchange between the women. The prayer is held and heard in the space between them. The spirit of the moment whispers from their mouths and releases from their hands, emanating back out toward the edges of the frame, toward the photographer hovering above, and toward the viewer here, now.

In Blackpentecostal Breath: The Aesthetics of Possibility, Ashon T. Crawley writes of the radical sociality and hospitality of Spirit of which theologians speak. He pays homage to David Hadley Jensen, who writes: “The Spirit who gives life is evident in hospitality shown toward strangers.” Crawley adds, “Such that we might say that Spirit—pneuma, breath, that which animates the body—is grounded in the necessity for sociality. Not only does Spirit give life, but that life is evident in how one leans towards others, how one engages with others in the world.” Radical sociality is the sharing of breath, and that is what Spirit is and does. We might consider this photograph—like the altar, icons, banner, flowers, water, feet, and the sanctuary itself—as the materiality of Spirit. The Spirit who gives life is evident in hospitality shown toward strangers. Watson met Parks one night at work. From the home altar to the neighborhood, to the sanctuary of St. Martin’s Spiritual Center, Watson helped Parks reorient his lens. He was able to express his desire for justice not only by visualizing the impact of racism on Black life, but by capturing how Black folks gather, worship, and live in ways that undermine the power that bigotry claims to hold. While the photographs that remain are still, the Spirit moves them. This Spirit emerges through the meeting of strangers—Parks, Watson, and the congregation—and through the rituals of collective faith and healing they welcomed a stranger to make visible beyond the church. The photographs render the walls of the sanctuary permeable, so much so that by sitting with the images and following Watson’s and Parks’s paths through them, we too find ourselves on holy ground.8

This essay first appeared in the Sanctuary Issue (vol. 28, no. 2: Summer 2022).

Jovonna Jones is a PhD candidate in African & African American Studies at Harvard University, and an incoming assistant professor of English and African & African Diaspora studies at Boston College. Her research centers Black women’s images, narratives, and criticisms in American culture and thought.NOTES

1. David Hadley Jensen, The Lord and Giver of Life: Perspectives on Constructive Pneumatology (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2008), xv, quoted in Ashon T. Crawley, Blackpentecostal Breath: The Aesthetics of Possibility, 1st ed. (New York: Fordham University Press, 2016), 40; “Summary,” Washington, DC August, 1942. Story of Mrs. Ella Watson, Negro Government Charwoman for 26 years, and Miscellaneous Scenes in Negro Section, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, accessed February 1, 2022, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004667419/.

2. Deborah Willis, “Ella Watson: The Empowered Woman of Gordon Parks’s ‘American Gothic,’” New York Times, May 14, 2018. Parks’s photograph Washington, DC Government Charwoman is better known as American Gothic.

3. Colleen McDannell, Picturing Faith: Photography and the Great Depression (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2004), 260.

4. Margarita Simon Guillory, Spiritual and Social Transformation in African American Spiritual Churches: More Than Conjurers (New York: Routledge, 2018), 67.

5. Stephen C. Wehmeyer, “‘Indians at the Door:’ Power and Placement on New Orleans Spiritual Church Altars,” Western Folklore 66, no. 1/2 (Winter/Spring 2007): 15–44.

6. Sally M. Promey, ed., Sensational Religion: Sensory Cultures in Material Practice (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2014), 399.

7. Guillory, Spiritual and Social Transformation in African American Spiritual Churches, 67.

8. Crawley, Blackpentecostal Breath, 40.