A farm on Peak’s Knob in Appalachian Virginia has shaped for generations the descendants of my great-great-grandfather Thomas Russell. Born enslaved in 1834, he purchased fifty acres only fourteen years after freedom. Over the years, members of my family grew Russell Farm to the two hundred acres presided over by James Arthur Russell, Thomas’s grandson and my grandfather. When Thomas brought his family to the farm, he came to a part of the Draper Mountain range standing high above the surrounding area at 3,360 feet above sea level—the highest point in Pulaski County. He saw a lush mountain covered in forests of beech, oak, hickory, maple, chestnut, chokeberry, and birch. He saw dignity, independence, abundance, home, and family. I hope he saw my generation—the fifth—ponder what to do with these two hundred acres and the farmhouse with that big round table still in the dining room. I hope he saw me.

Although my siblings and I grew up in Memphis, we are not of Memphis. We are Virginians—an identity instilled by my parents and forged during summers at Russell Farm. The sixth and seventh generations—all raised and residing in cities—have only seen pictures and heard stories, which we must keep sharing. If no one remembers, Russell Farm disappears and all that’s left is land and a farmhouse on the side of Peak’s Knob.

When Mama Russell (known to others as Elizabeth Holt Russell) died, my mother took me to Thomas Russell’s “old home place” in the holler. We stood where the porch used to be. Her voice changed. I traveled through time by riding that voice. At first, all I could see were the fireplace chimneys standing erect like sentinels, still guarding all that had been. Soon, I realized that the place under our feet was once the porch my mother stood on as a girl with her .22 rifle and shot between the ears the fox that had bothered her dog, Mape. My mother transformed for that moment into that girl. I saw through her eyes. Her memories became my memories, and I saw Russell Farm as a space connecting me to all that came before.

The cherry orchard encircles a grassy clearing down by the log house and barn. It must wonder why people don’t come anymore for the parties that used to happen under its branches. When my mother was a girl, the neighbors—Black families who filled the mountain—would walk along the trails carrying lanterns that they hung from the branches to cast a soft light upon the long tables filled with each woman’s specialty. At these community gatherings, Mommie joined the musicians to play her mandolin and raise her clear soprano voice. While she later added Lena Horne and others to her playlist, at this time Flatt and Scruggs and other country musicians filled her play-book. Those moments ended before I was born, but I picked those same cherry trees. On quiet evenings over the years, when the lightning bugs came out at dusk, I’d find some way to visit the orchard and I could almost hear the music.

Both my parents were born and raised in rural Virginia—my mother on Russell Farm, my father on a tobacco-growing farm in Southside Virginia that his father managed but did not own. We lived in Petersburg, a college town, until I was about five years old. Then we moved to Memphis, Tennessee.

I have often pondered how my parents managed to raise four children in the segregated South—in Memphis—and instill in us an unwavering sense of our own humanity, as did so many Black parents all over this country. Black parents faced unrelenting messages of inferiority, part of a daily life that was legally racially segregated, and buttressed by histories, social norms, and practices intended to produce “n—–s.” My parents showed us not to bow down. We went to the zoo as a family only once and on a Thursday, because Black people could go only on Thursdays. The one movie my parents took us to see was The Ten Commandments, because going to the movies normally meant buying a ticket at the side door and climbing up back stairs to the “colored” balcony, something they were unwilling to do. An exception was made for a film with God. We were never allowed to board the yellow buses that rumbled through the neighborhood gathering men, women, and children to pick or chop cotton in Mississippi and Arkansas.

At Russell Farm we lived a completely different life.

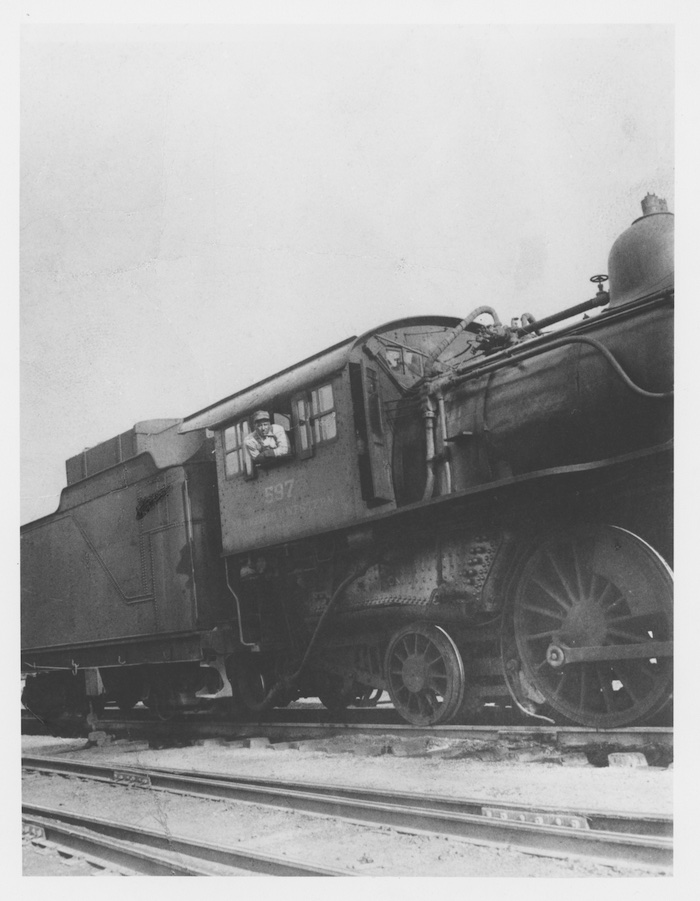

With the help of my great-uncle Randle, Granddaddy Russell had cut down timber on the land, milled it, and built with his own hands the existing four-bedroom, two-story farmhouse for his family. Every evening we watched the blue ridges across the valley as if we were their keepers. The wide front porch—every inch of railing covered with pampered, riot-of-color petunias—made space for grown folks sitting in rocking chairs and metal gliders, while we grandchildren mostly squabbled over whose turn was it was to ride Tony, the white wooden rocking horse Granddaddy made just for us. The porch was where the family gathered during summer evenings after supper watching dry lightning alight on peaks across the valley, like God’s dancers performing to an orchestra too far away for us to hear. We paused for each train whistle as Granddaddy called out the train number and said with pride, “Right on time!” That fierce whistle rolled up the mountain from the valley and spoke to me about places to go and adventures to be had, and as it left, it whispered ever so softly of possibilities.

To say that Mama and Daddy Russell were farmers is like saying an elephant is big. They bought only staples like coffee, tea, flour, sugar, and salt at the general store owned by ’Ole Aust, who was always after Daddy Russell’s land. Granddaddy said only sorry people ate store-bought food.

We had a beginning-of-summer ritual. Sturdy walking sticks lined the fence, and an astonishing collection of wide-brimmed straw hats were on the porch. Each child—my sisters Betty and Valeria, and my brother, Charles—got to choose a hat and a stick for the summer. Then off we went, following Mama Russell like ducklings, past the little cornfield right there at the house, through the gate, past the smoke house, down the winding path by the weathered double-seater outhouse, past the chicken coop on the right side of the path, ducks and geese on the left, then the corncrib, veering right at the almighty pig pen and on to the cherry orchard, big vegetable garden, huge cornfield that fed all the farm animals, and meadow.

Occasionally, when the pigs were safely hemmed in, Granddaddy would allow me to walk alone through the trees and down to a place he had created simply for his pleasure—a small pond surrounded by the softest, greenest grass. Unlike everything on the farm except Mama Russell’s flowers, it served no work purpose. For me, the pond was a magical place for fairies, wonder, and finding the occasional terrapin that I could bring up to the house and keep as a pet-of-the-day, returning it before dark. I don’t remember anyone ever going there with me; it was mine and Granddaddy’s.

It makes me smile today to remember that I was called “Grand-daddy’s Shadow.” He talked with me—explained things—like I was not a child, and he always had important work for me to do. I was very good at climbing up the corncrib stairs, helping to put the corncobs in the grinder and tossing kernels out to the ducks and geese. And I was pretty good at going into the hen-house, reaching under the hens who didn’t look too mean, and scooching out warm eggs to put in his egg basket. I have that egg basket still.

When it was time to prepare chickens for dinner, I stood at the gate and watched what happened over by the tree stump where Granddaddy chopped wood. That stump was where he would chop off the necks of the chickens, and this was followed by the mesmerizing sight of the headless body slinging blood and flapping ’til it didn’t. Mama Russell was more brutal. She stood in about the same spot, but she would wind that chicken up and pop its neck off. It was an awful, fascinating sight. I couldn’t not watch. I dreaded what was coming next. That chicken would be plunged into boiling water, a bunch of newspaper would be laid across my lap, and I’d sit there plucking that dead chicken. You have no idea of the scent that wafts off a dead chicken that has been dipped in boiling water. I was well past being a grown woman before I could touch raw chicken from the grocery store without wanting to be doing anything else.

On summer Sunday afternoons, we sat around what we lovingly called King Arthur’s Round Table in the dining room, flanked by two long windows that reached almost to the floor. If we promised to be still and quiet, Mama Russell would let us sit at one of those windows and almost touch magic—hummingbirds kissing gladiolas in her flower bed just on the other side of the glass. The heavy antique sideboard, covered with crisp white doi-lies made by Mama Holt, Mama Russell’s mother, held sky in the blue glass cake stand for her coconut cake, so high and fluffy it looked like a delicious cloud that might float away. Next to it was a milk-white ceramic stand showing off devil’s food cake. And there was a fresh pie made with the strawberries and rhubarb I gathered Saturday morning or with the blueberries we roamed the mountain to gather. Mama Russell knew all the special places where the wild blueberries grew, including the cemetery at “The Old Potter Place,” where we felt like the graves welcomed our company as Mama Russell told us all about who was buried there.

The dining table was covered with a crisp white tablecloth for the Blue Willow china. On top of that sat platters of ham, roasted chicken, and maybe rabbit or squirrel—always three meats for Sunday supper. My favorite was the corn pudding served in a ceramic dish advertising its contents by looking like an enormous ear of corn—the body of the dish replicated lush yellow corn as if it were still on the cob, and the top was lifted off by a conveniently curled green husk. My mother made corn pudding in that dish. I feel that I have my mother and Mama Russell with me in the kitchen when I, too, make corn pudding in it.

There were green beans, mashed potatoes and gravy, carrots, tomatoes and cucumbers, corn, and maybe the peas we shelled. When your senses just about couldn’t handle any more, here came the golden pocketbook yeast rolls with the heavenly scent that Mama Russell said came only when they were baked in a wood-burning oven. She kept her wood-burning stove even after Granddaddy bought her a new electric one. The ham came from Granddaddy’s smokehouse, an enormous dark place of scents that almost snuffed out your breath, with the bacon and hams contributed by whatever hog had been ready for slaughter last fall. Everything home-grown, home-raised, home-slaughtered. All this Thomas Russell saw.

We gathered in our Sunday clothes, taking our usual seats around the table, with great-great grandaddy Thomas Russell’s portrait presiding over us. Granddaddy’s portrait in his World War I uniform was there, too, a picture of a handsome young man serving his country in a racially segregated army. For Sunday, he traded his everyday uniform of overalls for a starched white shirt and three-piece suit, finished off with a fedora and carefully placed pocket watch and chain before he went to his Methodist church (which was led by a woman minister). He would dress like that for meetings of his fraternal lodge, too—the Knights of Pythias. Mama Russell dispensed with her everyday housedresses on Sundays and gussied up with pink dresses, brooches, matching shoes and purse, and always white gloves as she went to her Baptist church. I went to church with Mama Russell and entered a world so different from our quiet Episcopal church service in Memphis that I was mesmerized each Sunday wondering what might happen next.

Back home for Sunday supper, Mama Russell hardly sat—she mostly monitored everyone’s plates so she could extinguish any bare space. She popped up to come round with the bowl or platter, and when anyone said, “This is delicious, Mama Russell, but no thank you,” she plopped another serving on the plate. Then, Granddaddy told us stories: stories about the parties in the orchard, stories about how the ducks, geese, and chickens flocked down the mountain road every afternoon to greet Mommie, the only child, coming home from school. There was the story about how Mommie brought Daddy home for approval and Granddaddy took him out hunting while deciding whether he was good enough to join the family. Another about how the cannon on the town square really belonged to a man named Tiny and who he was and how his cannon came to be on the square. Sometimes Granddaddy would look at me and launch a story saying, “Now, when you were a boy . . .” Some true stories, some stories stuffed with lies that delight.

Still, some stories Granddaddy never talked about. Granddaddy worked as an engineer in the rail yard of the Norfolk and Western Railroad. I remember taking his lunch pail to him one day with Mommie and my brother, Charles. Imagine walking into the train yard and seeing your Granddaddy wearing his blue-striped engineer’s cap and driving a magnificent train engine right up to you and hopping off to give you a big hug. I’m glad I remember that feeling because when I was a grown woman, Mommie told me that the only time she saw Granddaddy cry was when he talked about being denied a promotion to drive the engine out of the yard because that position was only for white men. I didn’t know ’til then that I had seen white supremacy denying the humanity of my Granddaddy.

My mother went to a boarding school in Christiansburg because there was no high school for Black children in Pulaski County. I learned Granddaddy was a founder of the Pulaski County NAACP. After Mama Russell died, I helped my mother close up the farmhouse, and as we went through old trunks, there was one filled with yellowed newspaper clippings of Black resistance. My favorite was the clipping about the victory of Miss Mary Hamilton, who was convicted of contempt by the Alabama Supreme Court for refusing to answer questions until she was addressed as “Miss,” just as white women were. In Hamilton v. Alabama (1964), the Supreme Court took the surprising step of hearing the case, and it reversed the conviction. This was important to my grandparents.

They didn’t talk much at all about the Depression when Granddaddy worked for a dollar a day at a coal mine. Their story of the Depression was remembered in the basement, where three walls were filled with all the things we canned on the woodburning stove during the summer.

Black people eventually left the mountain to find work. My grandparents were the only Black folk left. Grandaddy kept trying to get Black people from town to come to the mountain and build the life of self-sufficiency, independence, and closeness to the land that he treasured.

No one came.

Now, we rent the place to the Berry family, descendants of Mr. Dallas Berry, who might be considered a “hillbilly” by some folk. Granddaddy saw something in that white man that others seemed to miss. That’s why Granddaddy sold Mr. Berry a piece of land up the road for his family compound. Granddaddy called him “Mr. Berry” and he called Granddaddy “Mr. Russell.” When I was a girl, our family sometimes had picnics with the Berry family at their place. I was captivated by their expressive, quirky way of speaking and came to appreciate its beauty. Mr. Berry’s family still lives up there; some of them live in our farmhouse.

The family sat at King Arthur’s Round Table for the last time in 1978, after putting Mama Russell in the family cemetery with all the other Russells. My son and grandchildren will never sit at that table, but they are steeped in the stories that tell us who we are. Today, the portraits of Thomas Russell and Granddaddy preside over my dining table. Now I realize the extraordinary contribution those summers made to nurturing my appreciation of my own humanity. My generation tells the stories about our summers and the stories we heard at the Round Table of King Arthur Russell, a Virginia Black man who walked the hills and hollers of Appalachia with the independence of saying no to ’Ole Aust, that white man who was always after his land.

This year we will walk the land with the sixth generation and their seventh-generation children. We will let our voices take them on that journey through the distance of time. They will see through our eyes, and all that was will once again come to life and connect them to all that came before. We will accompany them into the future for as long as they remember. Perhaps, as we are walking, we will feel Thomas Russell’s eyes upon us and we will wave to him.

This essay was published in the Black Geographies issue (vol. 29, no. 3: Summer 2023).

Barbara Phillips, a social justice feminist writer, was formerly a Ford Foundation program officer, associate professor of law at the University of Mississippi, Spaeth Fellow at Stanford Law School, voting rights litigator, and community organizer. Her essay “Imagine and Create the Third Reconstruction” is forthcoming.