Country Queers in Central Appalachia

Five years ago I moved home to the farm where I was raised in southeastern West Virginia. For a decade I had bought into the dominant narrative in LGBTQIA spaces that because I am queer I could never live back home. I was told—in not so many words—that I could not have my queerness and my mountains, too, that I would not be safe there, that I would not be able to survive, much less thrive. This is a common experience for those of us who have left the small towns and rural areas where we grew up.1

Mainstream LGBTQIA media and movements have long assumed a shared desire to escape from the country to more liberal “gay meccas” in urban and metropolitan areas. This assumption has been buoyed by stories of violent homophobic murders, such as those of Brandon Teena and Matthew Shepard—which, until very recently, have served as some of the only accessible evidence of rural queer existence. But for some of us this highly celebrated narrative of queer “success”—one in which you leave the farm and never look back, one in which you enter a fabulous landscape of glitter and queer dance parties—isn’t all that appealing. For many of us raised in the country, following this normative queer migration narrative rips us from the landscapes, communities, and traditions that are as much a part of ourselves as our queerness.2

Young people in the mountains are often encouraged to leave or escape, whether they are queer or not. Educational opportunities, jobs, clean water, and possibilities all beckon from flatter lands outside the jagged borders of our states. But young queer folks from the region often face additional pressure to go. Not only did I find deep contentment once I finally moved home to West Virginia, I also began to meet other young queer folks throughout Central Appalachia who had returned or who had never left, and who were determined to stay. I was introduced to many of them through the STAY Project (Stay Together Appalachian Youth), a regional network of young people who create, advocate for, and participate in safe, sustainable, engaging, and inclusive communities throughout Appalachia and beyond. STAY envisions an economically and environmentally sustainable Central Appalachia where young people have the power to build and participate in communities in which they can, and want to, stay.3

In July 2013 I founded an oral history project called Country Queers out of intense frustration at the lack of rural queer visibility. The project aims to document the experiences of rural and small town LGBTQIA folks throughout the United States in all their complexity. The first interviews I conducted for Country Queers took place at the 2013 STAY Summer Institute. In the excerpts that follow you’ll read stories of struggle and isolation, but also stories of joy, of pride, of triumph, of humor. I asked these young people about their experiences growing up queer in the mountains, about whether they felt pressured to leave. I asked them what was challenging about being queer in this place, and what was delightful about it. I asked them for funny stories, for ideas about what might make it easier for isolated rural queer folks to flourish in the mountains. I asked them about queer history in the counties where they were raised and about dreams and concerns for their futures. Their wisdom shines through. Each of these wonderful country queers has a lot to teach us about the often studied, rarely understood mountain region that we call home.4

Sam Gleaves

Wytheville, Virginia | August 2013

Sam was twenty at the time of our interview. He was raised in Wytheville, Virginia, and attended Berea College in Berea, Kentucky, where he studied folklore. Sam is a talented musician and songwriter, writing modern songs in a traditional style. His debut album of original tunes Ain’t We Brothers came out in the fall of 2015.

Rachel Garringer: What do you think is the biggest issue facing rural LGBTQ people?

Sam Gleaves: The initial obvious one is that lack of open community. The second is lack of a history. You don’t get told about: “Well, there was a same sex couple and they lived in such and such area of the county and they lived there for a long time together and they farmed or they did this,” and, you don’t have that kind of history in stories that you get in your family where we’re from . . . that’s part of your birthright. The stories about your family and that you get in the music and the socializing, the visiting. You get that history in all these different places that makes you feel rooted there.

Whereas when you discover you’re queer, I think a lot of people’s immediate response is to think, Suddenly I feel like I don’t belong here when my whole life I felt I did. Just that tension between having to reconcile your queer identity with your heritage, which can seem contrary at times, like two things that can’t go together. But I’ve found that those two things go together beautifully and that I’ve been able to embrace that.

RG: How?

SG: I had to be in a place where both of those could be celebrated with others first, and for me that was at Berea College. Because I made some friends who are country queers. And we started thinking, “Well, we’re Fabulous and we’re Appalachians, so we’re Fabulachians.”

And so that all came together and we clung to that word and used it, and used it, and used it, and used it when we first combined it. Because it set something right in ourselves. It announced that we were fully human. That we were whole. So that’s how I found it, was by connecting with other queer people from the same culture.

RG: What was your coming out experience like?

SG: I had an experience where I felt like my grandmother knew for the first time that I was gay. I was playing a gig somewhere, and my grandmother has been the greatest supporter of my music that I ever could have asked for. She’s a singer herself and sings gospel music and directs the children’s choir at church and all of that. She told me from the time I was little tiny that I had a pretty voice and that I should really pursue it, that I should share it. So, she was the foundation of me taking up music, period. She comes to hear me anytime that I’m playing locally, and I play in her kitchen all the time.

So, one time she came to this little local gig that I had in a bar, and I wanted to sing a song I had written that mentions explicitly . . . it just talks about the struggles of loving country boys! And there’s a line that talks about me kissing another man. And I thought to myself—I’d already started playing the song before I even thought about that reference—’cause the song was broader to me. I didn’t think, Oh, I shouldn’t share that ’cause it’s got those lines in it. I wasn’t thinking about outing myself. But then I got to the verse that was gonna out me and I thought, I can’t change the words on the spot, and why would I? So I just sung it.

“I never doubted for a second the love that we all share as family. We are all just learning how to communicate that love in our own way.”

And I remember—my grandfather and my grandmother—looking at the floor. I began to worry that I had upset them in some way, and there were people that we know from the community sitting all around them. But, I mean, it’s in a bar. So it’s not like everyone’s honed in on listening to me either. I have always felt like I could be myself when I sing at that bar, I’ve been singing there since I was in high school and all kinds of different folks from the community gather there. I think of it as our small town unofficial gay bar, but people of all ages and walks of life hang out in there. After I finished playing, my grandfather put his arm around me and said, “You need to be writing those songs. That’s how you can make your living.” I knew he was proud of me and that my grandmother was, too. I know they would go to any lengths to help me, and I would do the same for them. I never doubted for a second the love that we all share as family. We are all just learning how to communicate that love in our own way.

Ethan Hamblin

Ethan Hamblin was twenty-two years old at the time of our interview and a student at Berea College studying Appalachian Studies. After graduating, Ethan worked at the Foundation for Appalachian Kentucky. He recently began an MA program in rural sustainability at the National University of Ireland in Galway.

RG: How do you identify?

Ethan Hamblin: Sexually?

RG: Yeah.

EH: I love that! I thought you was gonna ask if I was a Democrat, because I am, and a Presbyterian! I’ll usually joke when people ask me that. I’ll always say, “Well, my religious beliefs are Democrat, and I am politically Presbyterian.” I love that. But . . . otherwise, I’m also an Appalachian, and a Kentuckian, and a Perry County-an.

But also, I do have to say this, since you’ve asked me how I identify. There’s a big debate over the word “Appalachian” a lot of times, and I am very leery about that word. Now, I’m an Appalachian Studies Major at Berea College, and having been in the academic world, it tends to be that people who use the word “Appalachian” are educated. And I don’t mean high school, I mean like college education, or are involved in “the movement” in some way.5

People from home, including my mother—and including me up until coming to Berea—we were mountain people. Simply mountain people. And that’s what’s important to us, is that we are from the mountains. Not, “We are from the Appalachian Mountains,” but we’re just good old mountain people. And so a lot of times when you’ll ask mom is she an Appalachian, she’ll say, “No, I’m just a good old mountain girl.” And so a lot of times I’ll say that, “I’m just a mountain boy.” I know that I’m an Appalachian, but there’s something, too, very strong about saying that you’re a mountain person, I think.

But anyway, I identify as a Fabulachian, which—I love using that term, which is a term that my good friend Sam Gleaves and I coined, you know, putting the words fabulous and Appalachian together. That term has been used by other groups after—make sure that’s in there—after we used that for our research. But the term is Fabulachian and it is used to represent the queer community in the Appalachian region.

RG: Do you think being from the country made it harder to come out?

EH: Being from a rural place? Compared to an urban place? Yes. However, it works for me, and the reason being is because being from the country and being gay are very similar. Here’s the reason why: because they’re both marginalized groups. When you’re gay and in the country, you’re a marginalized group within a marginalized group. But the reason I think they’re very similar is the idea of community.

In a rural place, community is the main thing, which I’ve already talked a lot about. When you are gay, or in the LGBTQ community, in the queer alphabet world, you’re part of a community. I have found those two communities to be very similar. Which is why I love the Fabulachian Movement, because what better way to bring my mountain culture and my queer identity together? Because both of them are these wild, crazy, very communal ways of thinking. And when you put those together, it’s powerful—very, very powerful.

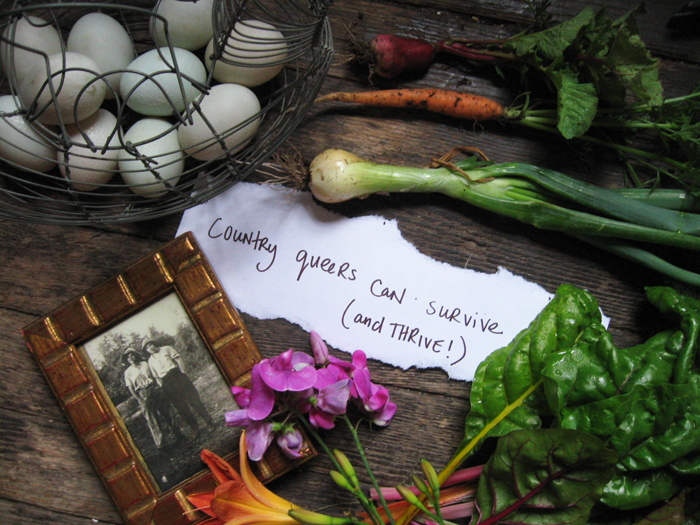

But, yes. I think it would have been [harder] compared to an urban area, but I think that country queers can handle things a lot better than urban queers can. We are survivors. Country queers are survivors.

Elandria Williams

Knoxville and Powell, Tennessee | August 2013

Raised in Powell, Tennessee, and now residing in Knoxville, Elandria was thirty-four at the time of our interview. Elandria works at the Highlander Education and Research Center with the Appalachian Transition Fellowship Program, and is a long time youth advocate and organizer.

RG: What do you think the largest issues facing LGBTQ people are in general, and then do you think it’s the same or different for rural LGBTQ people?

Elandria Williams: One of the largest struggles to me is how to talk about race and class in the queer community. That’s huge. I think there are large swaths of the queer community that don’t want to deal with it at all. Which is why I think marriage equality was great, people took off, and you’re like, Now what? Are we really gonna deal with other things that people need? Like [issues around] bullying, around stuff around prisons, around economics—knowing that a lot of the poorest people are people who are differently-abled and queer, combined.

I think we’re still at a place where people think queer means white. And I think that almost all issues that impact everybody are the biggest issues that queer people face, because queer people have every other thing in back of them. If the country is dealing with an economic recession, the biggest issue queer people face is the economic recession. Because at the end of the day, everyone needs a job. So, that’s what I believe. I think there’s a different bent on it, around how it impacts queer people in ways that it does not impact hetero people.

I actually think it’s different in rural areas than in urban. In rural areas people are still fighting for survival. Actually—no, that’s not true. That can be urban, too. Somebody just got murdered a couple weeks ago for being trans—a trans man just got murdered and a trans female just got murdered a month ago in New Orleans . . . both black of course. And the kid got murdered in Miami. Tazered. Like a week ago. So I think that is maybe the biggest fear still? Right? Like what does it mean for people to be murdered because of their identity? And the way they express? That to me is huge.6

I think in rural spaces? Communities are small. I think it’s hard to figure out how to find a relationship. How to maintain. How do you deal with your family? How do you maintain stability? And how do you have a family? Whatever family means to you, right? How do you have a job, so that you’re actually successful in your life in whatever that means? I think it’s harder in rural areas than in cities. And in many ways it’s because most people in rural areas are from those rural areas. So it’s not just about you. It’s about your family, it’s about their family’s community, and people and their lovely mouths wagging.

I think that’s actually the hardest thing about being in a rural area that you’re from. Is that people will always remember you, and they’ll remember your family, and you’re always connected back in. And small town gossip. That to me is the hardest thing. And churches, did we talk about churches? I’m sure lots of people talk about churches.

Ada Smith

Whitesburg, Kentucky | July 2016

Ada works as the Development Director for Appalshop in Whitesburg, Kentucky, where she was raised. She is a founding member of the STAY Project, and is on the board of Southerners On New Ground SONG). Ada was twenty-nine at the time of this interview.

RG: How do you feel about being queer and country?

Ada Smith: In general, it’s great. I freaking love where I’m from. I love it, I love it, I love it.

I think, to me, I love being country and queer, and I feel like there’s a lot of possibility. And also I really recognize how much whiteness has to do with that. Personally, I am trying to better understand and create spaces and infrastructure [where] it’s not just about whiteness for that to happen. Clearly, there are structural issues. You can’t just make a space and say, “Welcome! Everything’s fine!”

But I believe in this region that there is not so much a problem—anymore—about being queer and rural and whether or not you can stay, as long as you’re white. I think there is a problem in Central Appalachia about being queer, and rural, and a person of color. Not to say that queer rural white people don’t ever deal with some bullshit, but for the most part people can push through it, find support structures.

I can imagine a time that no queer rural people felt like they belonged. But that has shifted. Now, in general, in Central Appalachia, can we have rural queer people of color that can be their full selves? Just being rural people of color that aren’t getting attacked all the time? When it’s just about me, I think it’s great. When I start thinking about being a Country Queer and what that looks like and what that means, I got a lot of complicated feelings about it and what specifically for me—as a white country queer—what responsibility I have to not just be like, “Oh, everything’s fine for me, so what’s the problem?”

Kenny Bilbrey

Whitesburg, Kentucky | July 2016

Kenny was raised in Wytheville, Virginia, and now lives in Whitesburg, Kentucky, where they work as the first ever STAY Project Coordinator. They identify as transgender, use they/them/theirs pronouns, and were twenty-four at the time of our interview.

RG: Do you want to talk at all, or do you have thoughts about access to health care for gender-non-conforming people in rural areas versus in urban ones?

Kenny Bilbrey: First of all, I would add that access to quality affordable healthcare for any person in this county and in so many rural areas is horrible. So many people don’t have access to health insurance, there’s very few doctors, a lot of healthcare providers that come in here come here from somewhere else and are getting paid to be here in this specific place for a certain amount of time. And then they leave and they’re not invested in the place.

So, while there are some quality healthcare [options], it’s not nearly at the scale for most people and it’s very expensive, as we know. When you add like specialties, or different things that people aren’t used to navigating, it becomes this huge emptiness.

I struggled for a very long time to find a physician that I felt comfortable with just as a primary care doctor. There’s a nurse practitioner in town and I won’t say her name, but she has taken very good care of me. I’m lucky to find this one person in this one place, but she still doesn’t have resources or education on these issues. She’s been willing to be very kind to me and patient, she’s trying to figure out where she could refer me to. But still, she’s like, “We could send you to Louisville,” which is four hours away from here, “or Lexington,” which is two and a half, or “Knoxville,” which is two and a half. So, maybe it would be possible for me to get out and go to that every now and again. But I’m lucky enough to be a person who has a full-time job and health insurance. That’s the only way that I’m able to do that, is because I have access to these certain things, but so many people don’t and that makes it even more difficult.

It has me questioning, like, do I need to be in a city where I can have access to all these things and I just don’t have to fight for them all the time or drive three hours and back for them? I know where I want to be and what makes me happy, but if I want a queer community, or if I want access to the specific healthcare, or if I want to be in a place that’s gonna have other people where I could learn from their experience, as far as being trans . . . I’m just always straddling a line of, I can do this but I won’t have this. That seems pretty negative. There’s also a lot of wonderful things about my life and getting to be me where I am, but I can’t really be all of me easily.

Ivy Brashier

Viper, Kentucky | August 2013

Ivy was 26 at the time of our interview. Raised in Viper, Kentucky, Ivy now lives in Lexington, Kentucky, where she works at Mountain Association for Community Economic Development (MACED) as Appalachian Transition and Communications Associate.

RG: Do you know of other queer people who have lived in your community before you?

Ivy Brashier: Yes. There is a lesbian couple who lives just down the road from where I grew up. They are probably in their forties. They have two sons, but they are from one of the women’s previous marriage. They went to Viper Elementary School, and my mom is a teacher, so she taught both of those boys. I don’t know much about them other than that. They came to our church for a little while. But everybody knew that they were together, and they were living in this house, but nobody ever had an issue with it.

In the mountains where I’m from . . . if they know you’re a good person, people just stay out of your business. It’s like, “You stay out of my business, I’ll stay out of yours. You don’t harm my family, or do wrong by my family, and we’ll be fine.” And they just sort of let you be.

But then also the mayor of Vicco [Kentucky], who is openly gay, Johnny Cummings, has lived in Vicco his entire life and been out his entire life. People just don’t have an issue with that, and he is loved among the region. Everybody knows Johnny, and he cuts everybody’s hair and all this kind of stuff. So yeah, there are a couple of people . . . and also, a couple of my cousins, but they would never admit that, so I won’t name them.7

“I think a struggle for Appalachian LGBTQ people, young people especially, is that they feel like this place is not where they belong, but they also simultaneously do belong and feel that belonging.”

RG: Is there anything you want to say to other LGBTQ people in rural or small town areas?

IB: You don’t have to look outside the region to find a place where you belong. I think a struggle for Appalachian LGBTQ people, young people especially, is that they feel like this place is not where they belong, but they also simultaneously do belong and feel that belonging. We have this part of ourselves that is always wanting to be in the mountains, and always wanting to be home. And, I know for myself it’s a struggle, not because of being gay, but because of being outside the region. It’s always a struggle to not be home.

Inherent in the process of staying for young queer Central Appalachians is the need to rename our identities, to connect to other LGBTQIA people in the mountains, and to demand that we belong, that we exist, and that we have been here all along. To use Sam Gleaves’s words as a refrain: “ . . . we clung to [Fabulachians] and used it, and used it, and used it, and used it when we first combined it. Because it set something right in ourselves. It announced that we were fully human. That we were whole.”

The STAY Project continues to be a space where young queer Central Appalachians find one another and work together to build the kinds of inclusive communities we know our region needs. After finally moving home in 2011, it was through STAY that I was able to find a community where my queerness and my countryness were celebrated simultaneously. It was in large part because of the support I received from STAY that I gained the confidence to launch Country Queers, with no idea whether or not it would “work.” It is my hope that the ongoing Country Queers Project supports other rural queer people in the quest to find a sense of wholeness, a sense of completeness, and a sense of country queer community, in the mountains and beyond.

This essay first appeared in the Appalachia issue (vol. 23, no. 1: Spring 2017).

Rae Garringer hails from a sheep farm in southeastern West Virginia. They are the founder and director of the ongoing oral history project Country Queers, which documents the diverse experiences of rural and small town LGBTQIA folks in the United States. Garringer received a BA from Hampshire College and an MA in folklore from UNC-Chapel Hill.

Notes

1. LGBTQIA stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, and asexual. I use “queer” as an umbrella term to reference all of these identities (in addition to others not represented in this list such as: pansexual, two spirit, agendered, genderqueer, etc.). For more information about these terms, and the ever evolving process of naming identities and desires within queer communities, visit: http://itspronouncedmetrosexual.com/2013/01/a-comprehensive-list-of-lgbtq-term-definitions/#sthash.cUWlFPec.dpbs.

2. Brandon Teena was a white twenty-one-year-old trans man who was murdered in Falls City, Nebraska, on December 31, 1993. Teena’s murder was made famous through the 1999 film Boys Don’t Cry; Matthew Shepard was a twenty-two-year-old white gay man who was murdered in Laramie, Wyoming, in 1998; I don’t aim to dismiss the very real history of violence towards queer folks in rural spaces, but the narrative that places violence and oppression in rural communities and safety and liberation in urban ones is simply false. In reality, queer and transgender people of color—in particular, trans women of color—are the most common victims of violent hate crimes in the United States, whether in rural or urban spaces. The national attention to Brandon Teena and Matthew Shepard’s murders has worked to create a perception that rural areas are unsafe for queer people, but also has drawn attention away from the ways in which racism and homophobia coalesce to put trans and queer people of color most at risk for violence in the United States. For a list of the trans people murdered in 2016, see: http://www.hrc.org/resources/violence-against-the-transgender-community-in-2016.

3. Since 2008, the STAY Project has brought more than 200 different young Appalachians together at five regional gatherings to help build a brighter future for Appalachian youth. STAY’s geographic reach extends to all regions of the five Central Appalachian states: Kentucky, West Virginia, Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee. For more information about the STAY Project, see: www.thestayproject.com.

4. The goal of Country Queers is to document the diverse experiences of rural and small town LGBTQIA folks throughout the United States—across similarities in experience, as well as differences based on race, class, gender identity, age, religion, occupation, immigration status, ability, and other parts of our identities. Since 2013, I’ve interviewed 45 amazing country queers in 14 states. The project is ongoing. See more at www.countryqueers.com; The STAY Summer Institute is STAY’s largest membership gathering of the year, where young people from throughout Central Appalachia come together to build community, participate in popular education and organizing trainings, and work toward a more sustainable and inclusive future. Because these interviews took place at the STAY Summer Institute, all of the following people are connected to one another through community organizing and social justice networks within the mountains. STAY was founded with support from Highlander Research and Education Center in Tennessee, Appalshop in Kentucky, and High Rocks in West Virginia. Additionally, all of the people presented in this collection of interviews have college degrees and have had the opportunity to leave the places in which they were raised. The Country Queers Project at large works to document rural queer experiences across a wide range of intersecting identities, including race, class, education, and geography.

5. In social justice and organizing spaces, many people refer to the collective work that organizers are doing across the nation and the world for justice as “the movement.”

6. While I don’t know which murders Elandria is referring to specifically, murders of transgender people—in particular trans people of color—continue to occur at alarming rates in the United States. The following article by the Advocate lists the known murders of trans people in 2013. Trans murders often go unreported as such due to the police mis-gendering the victim while filing reports. Actual numbers are likely much higher. See: www.advocate.com/crime/2013/11/20/transgender-day-remembrance-those-weve-lost-2013.

7. In January 2013, Vicco, Kentucky, passed a non-discrimination ordinance, earning the town the title of “Smallest Town in America to Pass a Non-Discrimination Ordinance.” Johnny Cummings, a hairdresser and the mayor of Vicco, Kentucky, gained national attention after he was featured on the Colbert Report on August 14, 2013.