Scholars Eric Savoy and Robert Martin describe American Gothic as a “discursive field in which a metonymic national ‘self’ is undone by the return of its repressed Otherness.” In What Has Been Will Be Again (2020–2022), photographer Jared Ragland underscores the significance not only of his art form but of place as an important contributor to this critical discourse about American national identity. Initially commissioned as a Do Good Fund artist residency, Ragland’s documentary photography project grapples with manifestations of a problematic past resurfacing in present-day Alabama. Its geographic focus and connection to a journalistic, literary, and artistic heritage identify the historical realities, culture, and climate of the South as particularly well suited to destabilize American idealism and force a reckoning with uncomfortable truths about the nation and ourselves.

Working deep in territory that Allison Graham has called a “repository of national repressions,” Ragland traveled to each of his home state’s sixty-seven counties, often via routes connected to a brutal colonial legacy—following the path of Hernando de Soto’s 1540 expedition, the Trail of Tears, the Old Federal Road, and the slave ship Clotilda. This methodology adopts a core tenet held by scholars of place studies, who assert that pilgrimages to sites where historical events happened (but are not happening anymore) are meaningful because the places themselves are imbued with a particular energy or spirit of authenticity. The energy of these specific historical sites is often charged with anxiety, violence, and peculiarity.

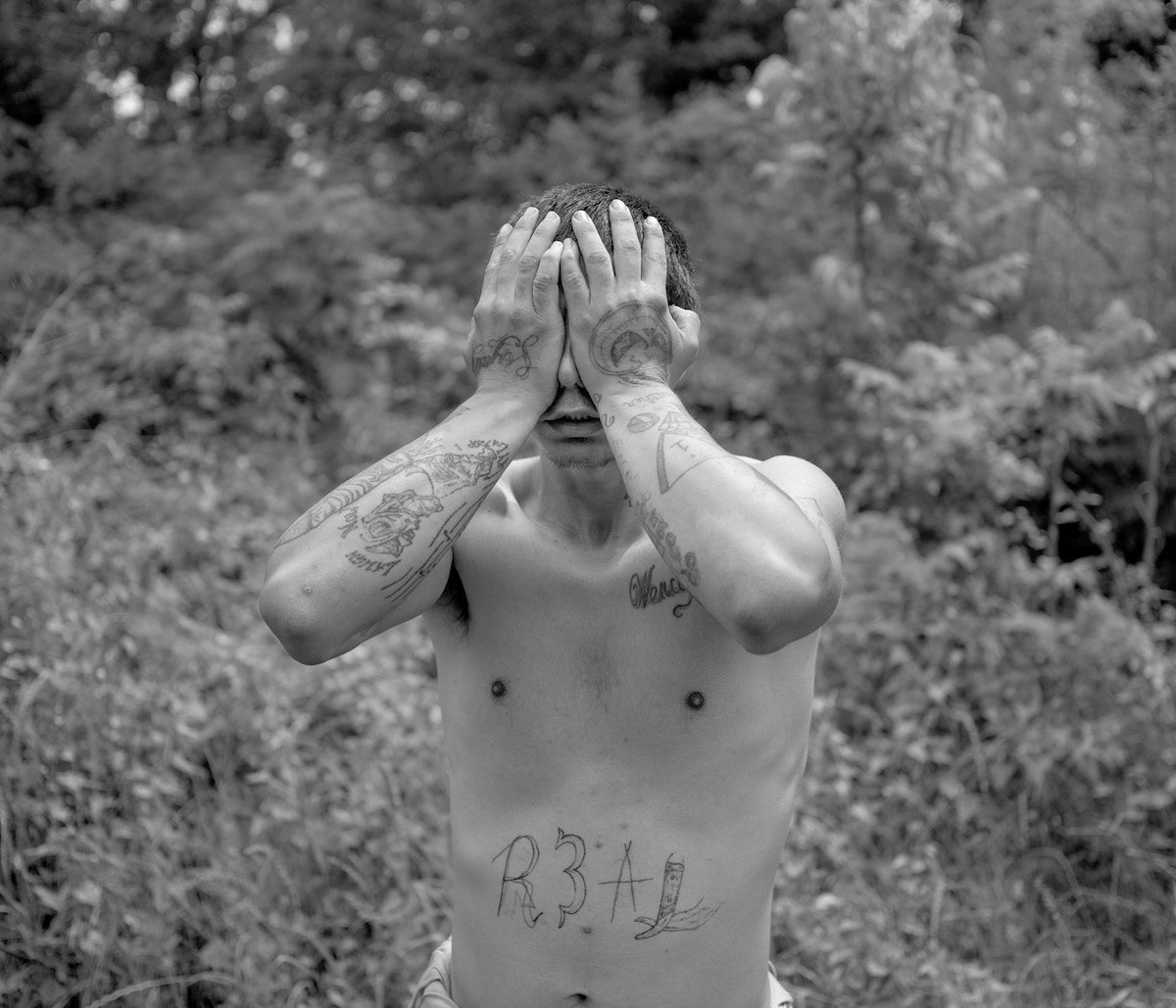

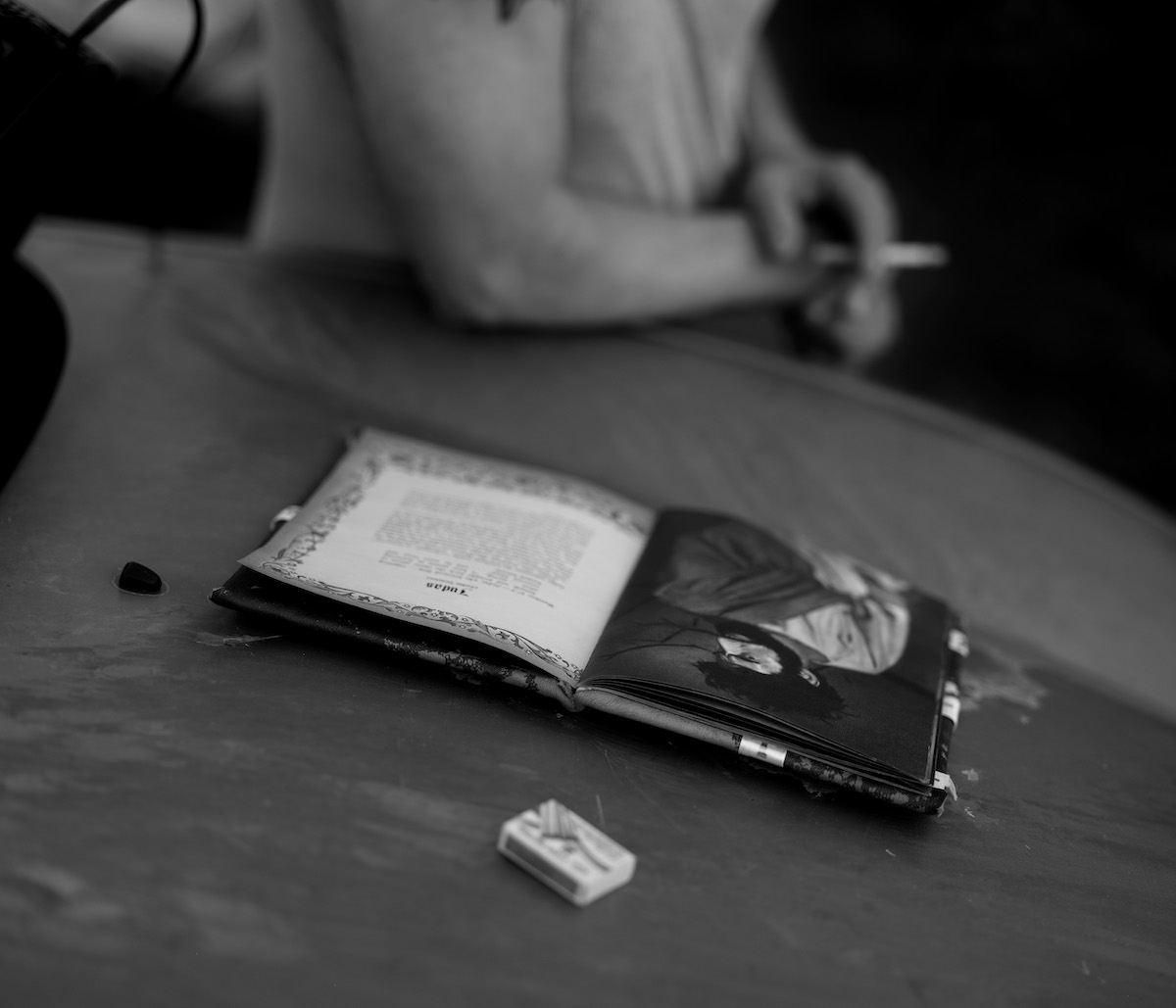

In keeping with the theme of walking in the footsteps of those who came before, Ragland’s images are made in the tradition of photographers who helped shape and continue the Southern Gothic visual aesthetic, merging the worlds of southern reportage by Walker Evans with more contemporary, expressive works by Ralph Eugene Meatyard, Mark Steinmetz, and Debbie Fleming Caffery. Pictures like “Michael Farmer,” “Perine Well,” and “Macon County, Ala.” are disquieting studies in black and white that depict “outsiders,” haunting landscapes, and decay, imbued with a pensive fear, tension, and sense of mortality. Despite their strangeness, the photographs are visually familiar, creating a throughline with twentieth-century representations of Southern Gothic themes, suggesting the continued relevance of the social commentary on race, poverty, and marginalization embodied in earlier artistic works.

Lest the visual familiarity of the work breed a sort of comfortable, passive viewing, Ragland’s sequencing of images and inclusion of meticulously researched captions require the viewer to intellectually engage with historical trauma and current sociopolitical issues. For example, “Sumter County, Alabama” depicts a forested landscape with an eerie human silhouette made of metal, yet is described in the caption as the largest hazardous waste site in the United States, adjacent to a town where 90 percent of residents are Black, and actively polluting the aquifer that provides water to nearby communities. By bookending this image, which opens the issue, with the last image here—”The Old Plateau Cemetery,” illustrating a sun-dappled graveyard in Africatown, near where the slave ship Clotilda was scuttled—Ragland produces a powerful commentary on environmental injustice and its connection to historical racism. What Has Been Will Be Again therefore meets, then disrupts, audience expectations for the Southern Gothic, challenging the master narrative of American exceptionalism and egalitarianism by depicting past and present problems of place.

For generations, Michael Farmer’s family has lived in Spring Hill, where the predominantly Black community has faced a history of racial violence and voter disenfranchisement. On November 3, 1874, a white mob attacked the Spring Hill polling station, destroyed the ballot box, burned the ballots, and murdered the election supervisor’s son. When asked what he hoped might come from the 2020 presidential election, Farmer said, “I hope the young folks might think about what their ancestors came through to get where we are.”

Yoholo-Micco, chieftain of the Upper Creek town of Eufala, is said to have addressed the Alabama Legislature in 1836 at the state capital in Tuscaloosa before departing the ancestral Muscogee homelands on the Trail of Tears. Yoholo-Micco’s actual words are unknown, but the colonial writers of history have painted the Creek leader as one who accepted Indigenous removal with an air of romantic resignation, going so far as to contrive his final words to whitewash the genocide that had taken place over three-hundred-plus years. Yoholo-Micco’s apocryphal address—which has been reproduced in Alabama history books and grade school curriculum for decades—reads, in part: “I come here, brothers, to see the great house of Alabama and the men who make laws and say farewell in brotherly kindness before I go to the far west, where my people are now going. In time gone by I have thought that the white men wanted to bring burden and ache of heart among my people in driving them from their homes and yoking them with laws they do not understand. But I have now become satisfied that they are not unfriendly toward us, but that they wish us well.”

Uniontown is home to around two thousand people, 91 percent of whom are Black. The economically depressed city faces a multitude of environmental issues that affect the health and lives of its residents, including the nearly four million tons of toxic coal ash held in the nearby Arrowhead landfill. At the time of a 2017 report by the Alabama State Nurses Association, Uniontown had only one doctor’s office and no public transportation system, with the nearest hospitals located more than thirty miles away.

The Apalachicola Fort Site is located across the Chattahoochee River from present-day US Airborne School at Fort Benning, Georgia. The Spanish established the wattle-and-daub blockhouse fort in 1690 in attempts to maintain influence among the Lower Creek people, who responded to the construction of the fort site by migrating to English-controlled areas. This move undermined the purpose of the fort, which was already encumbered by a long supply line. It was consequently abandoned after just one year of use, and largely demolished by the Spanish prior to their departure.

Carbon Hill has endured a troubled history of racism and violence. Just weeks before it was established as a mining and railroad community in 1891 and nicknamed “The Village of Love and Luck,” a group of white coal miners devolved into a violent mob upon hearing rumor of layoffs. Afraid their jobs would be given to Black citizens, they drove Black people from their homes and terrorized the town. Between 2019 and 2020, mayor Mark Chambers published several inflammatory statements on Facebook, including a call to “kill out” the LGBTQIA community and aiming racist remarks at the Black Lives Matter movement.

Located on the Chattahoochee River near the former Creek centers of Coweta and Yuchi Town, Phenix City has a fraught and violent history. In the mid-twentieth century, it was home to the Dixie Mafia, and as murders, prostitution, and gambling ran rampant, the town became known as “the wickedest city in the United States.”

The area now known as Old Cahawba was first occupied by large populations of Paleoindians; then, from 1000 to 1500 CE, the Mississippian period brought agriculture and mound builders. Spanish conquistadors were welcomed to a walled city with palisades, yet the Afro-Eurasian diseases the explorers brought with them killed thousands of Indigenous people in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The remaining Native peoples were killed or displaced by an even greater influx of Europeans. By the early nineteenth century, the dirt from the ancient mounds at Cahawba was used to build railroad beds, and the town briefly served as the state capital of Alabama. At the time it was dug in the 1850s, the Perine Well, at seven hundred to nine hundred feet deep, was the second-largest known well in the world, feeding cool water through a system of pipes to “air condition” a twenty-six-room brick mansion. Cahawba became a ghost town shortly after the Civil War, largely due to recurring floods. By the late 1800s, the town site was purchased for $500 and its buildings demolished.

Over recent years, Macon County citizens, led by former Tuskegee mayor and city councilman Johnny Ford, have attempted to cover and remove the Confederate monument in the town square. Erected by the United Daughters of the Confederacy in 1906 on a plot gifted to the UDC by the county government, the statue became the centerpiece of the whites-only park—a white supremacist symbol placed in the heart of one of the most historically and culturally significant African American communities in the nation. In July 2021, Ford attempted to topple the monument with a concrete saw, cutting through a leg before being stopped by the local sheriff. It was soon repaired by the UDC. “We cannot, in Tuskegee, Alabama, the birthplace of Rosa Parks, the home of the Tuskegee Airmen, the home of Tuskegee University, this historic city, have a Confederate statue in a park built for white people,” Ford declared to the Associated Press. Yet recent legal efforts by city officials to remove the statue have stalled, particularly in light of state legislation written to protect Confederate monuments.

Once home to some of America’s greatest heroes and civil rights leaders including Booker T. Washington, George Washington Carver, Zora Neale Hurston, Rosa Parks, and the Tuskegee Airmen, Macon County is also the site of some of America’s worst and most egregious civil rights injustices. In 1814 the US Army built Fort Bainbridge near several important Muscogee (Creek) towns to guard a supply route into Creek territory and serve as a foothold for Indigenous Removal in southwest Alabama. After the Indian Removal Act of 1830, white landowners established plantations throughout Macon County using extensive forced labor of enslaved people. Between 1932 and 1972, investigators from United States Public Health Service and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention enrolled six hundred African American men from Macon County in “The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male.” Participants were not informed of the nature of the experiment and left untreated for forty years. More than one hundred men died as a result.

Between 1855 and 1856, wealthy Mobile shipyard owner Timothy Meaher built the Clotilda, an eighty-six-foot-long two-masted schooner originally designed for the lumber trade. While the 1807 Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves had been law for more than fifty years, Meaher made a wager that he could use the ship to successfully smuggle enslaved people into the United States. Captained by William Foster, the Clotilda made its way to West Africa in spring of 1860, and on May 15, one hundred twenty-five prisoners of the King of Dahomey (now Benin) were purchased at the port of Ouidah. One hundred ten people were boarded onto the vessel and chained together in a cramped cargo hold for the forty-five-day voyage. They were allowed on deck only once a week. By early July, the Clotilda arrived in Mobile Bay, where it was towed under the cover of night up the Spanish River to Twelve Mile Island. The captives were then transferred to a steamboat, and Foster burned the Clotilda before scuttling it in a ship graveyard along the river’s edge, just yards offshore from Meaher’s property. The enslaved people were mostly distributed to the financial backers of the Clotilda venture, with Meaher retaining thirty people. Meaher regularly bragged about his crime, and the ship’s arrival was an open secret in Mobile. In 1861, the federal government prosecuted Meaher and Foster for illegal slave importation, but the case was dismissed for lack of evidence. Following emancipation, many of the formerly enslaved people returned to land owned by Meaher on the Mobile-Tensaw River Delta, just a short distance away from where the Clotilda had been scuttled. There, they founded the independent community of Africatown and maintained use of the Yoruba language and cultural traditions into the 1950s. The town thrived for decades but declined after the closure of several major local industries and the development of interstates and roadways that physically divided the neighborhood. Today, some one hundred descendants of the survivors of the Clotilda still live in Africatown and seek recognition of their historic town site while fighting significant ecological and economic hurdles.

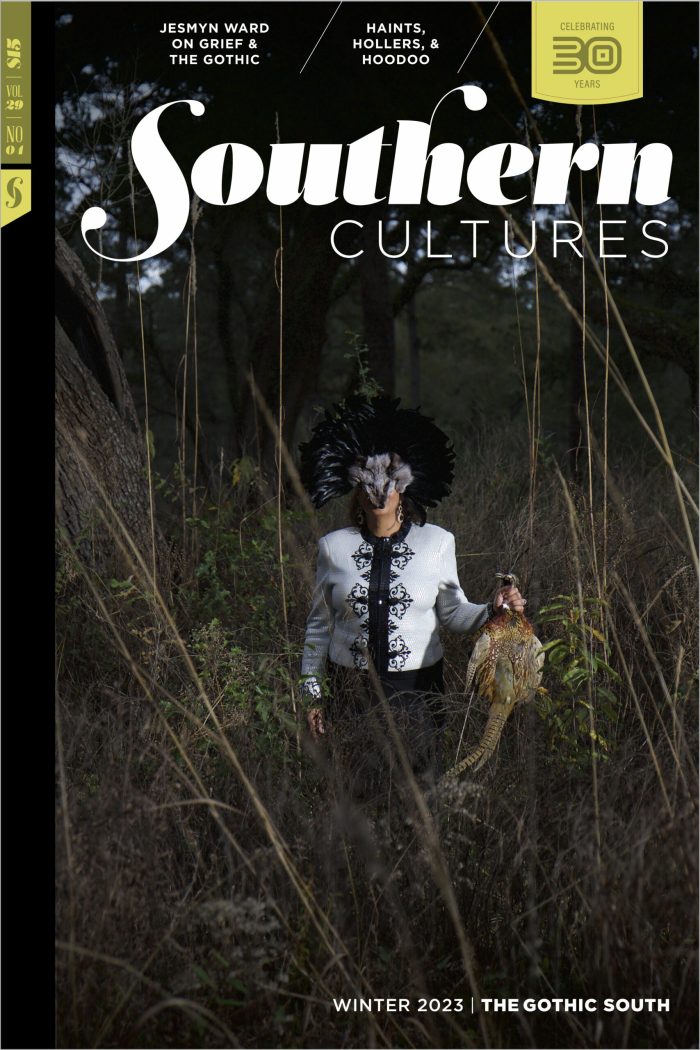

This essay is from The Gothic South issue (vol. 29, no. 4: Winter 2023).

JARED RAGLAND, MFA (Tulane University), is an assistant professor of photography at Utah State University. His socially conscious visual practice confronts issues of identity, marginalization, and the history of place through social science, literary, and historical research methodologies.

CATHERINE WILKINS, PhD (Tulane University), an instructor and acting associate dean in the Judy Genshaft Honors College at the University of South Florida, is committed to community-engaged teaching and research practices. A cultural historian, Wilkins focuses on visual and literary production—from the nineteenth century to today—and its intersection with sociopolitical issues.