Each fall, the Country Music Association presents an awards show that it pioneered in 1967, a once-a-year opportunity to celebrate musicians and industry personnel with titles such as Entertainer of the Year and Song of the Year. Celebrating one winner in each category, these awards suggest to audiences that they summarize the state of country music today, essentially crowning the “best” of the genre. Even a cursory glance back in time, however, tells a much more interesting and complicated story.

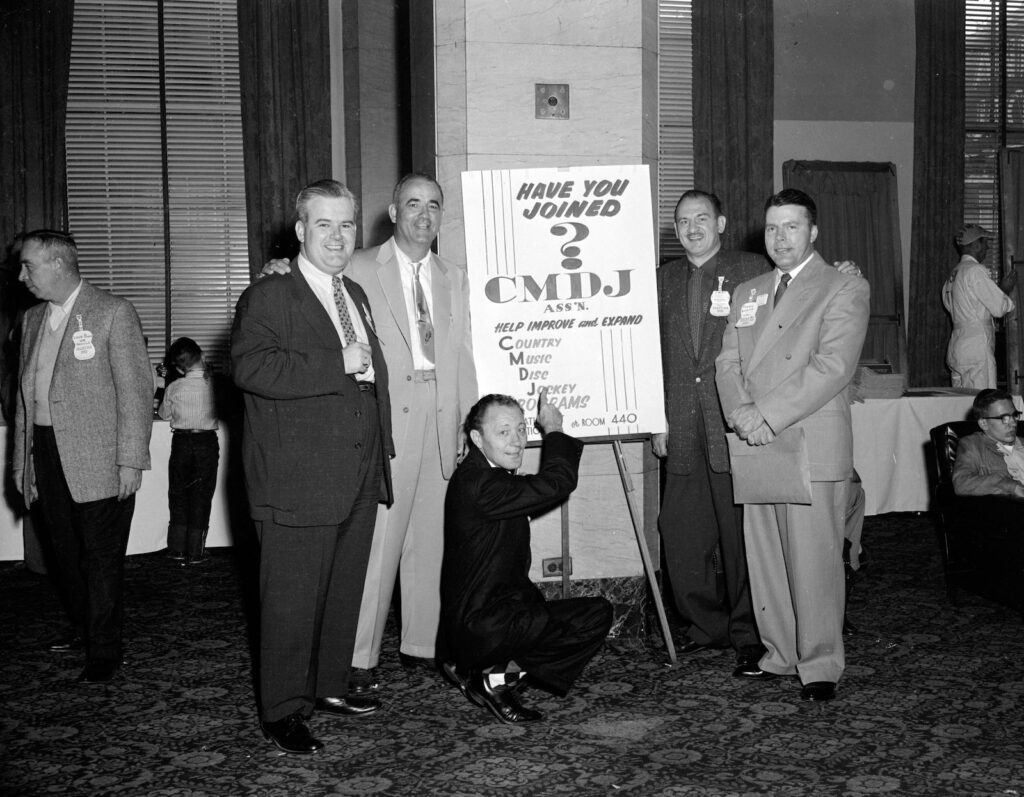

In 1952, a group of radio disc jockeys banded together to form the Country Music Disc Jockeys Association (CMDJA), a professional organization whose mission was to preserve and promote the music by which they earned their livelihoods, and whose prevalence as a genre was threatened by a growing surge of popular music and newfangled rock ‘n’ roll. In those fledgling organizational roots, we find one of the themes that shapes the CMAs to the present: how might country music maintain a distinctive identity, differentiated from pop and rock, that satisfies fans whose sense of self is rooted in country music, while also appealing to as broad a fan base as possible? Six years later, the CMDJA morphed into a new organization, the Country Music Association, anchored in Nashville, which took on a charge to represent multiple branches of the country music industry. In 1967, the organization launched an annual awards show, albeit not the first—a competing trade organization known as the Academy of Country Music, situated on the west coast and expressly created to market and celebrate country music that was too renegade for the Nashville establishment, had started their awards show a year earlier. Nearly six decades later, the CMA awards draw the attention of fans and industry professionals alike each year, not to present some pristine slate of the “best” country music (as if any such judgment were even possible), but instead to undertake a persuasive gate-keeping exercise whose goal is to define, preserve, and disseminate an industry-generated narrative about a genre whose boundaries are constantly in negotiation.

The CMA’s roots in the radio industry show up in their awards, which include categories both for radio stations and for broadcast personalities (show hosts or DJs in vernacular descriptions). Hidden behind those categories is the bold recognition that good ol’ AM/FM format radio still matters to the country music industry and audience, far more than one might suspect in a world of streaming services and on-demand access to music. My college students almost never talk about listening to music on the radio, and certainly not about finding artists or songs that way. Nonetheless, research continues to show that around 82 percent of adults in the US listen to terrestrial radio each week (Nielsen Media Research Data), and for adults over age 35, about 74 percent of their total audio listening time comes from radio. Country music continues to hold sway over the terrestrial radio industry as the most common format (followed by talk radio) for stations nationwide.

These numbers remind us that, by sheer volume of songs and overall minutes invested by listeners, radio is still highly relevant to any conversation about country music in ways that social media and popular culture tend to ignore. Trade publications that chart music listener trends understand that fact: Billboard, for instance, publishes not only a “Hot Country Songs” chart, whose entries are compiled from a combination of radio airplay, streaming, and sales data, but also a “Country Airplay” chart, whose entries reflect only radio airplay. These two charts are symptoms of a country music industry—and listener base—who are deeply invested in sometimes-heated negotiations about what music and artists are granted status within the genre. In practice, artists—especially pop-crossover artists—show up more regularly on the “Hot Country Songs” chart, while the radio industry maintains a stricter hold on which artists and songs make it into airplay circulation on self-proclaimed bona fide country stations. And the CMA awards take a similar stance: for the most part, their awards draw attention to musicians and songs that are most entrenched in the commercial country music industry. Those awards are selected by votes from the association’s members, not the fans. In their simplest interpretation, the CMA awards remind us that there is a massive quantity of music every day that is curated by a relatively small number of industry professionals and consumed mostly passively by its audiences. And those mechanisms serve to tell the fans what the industry considers to be country music, rather than the other way around.

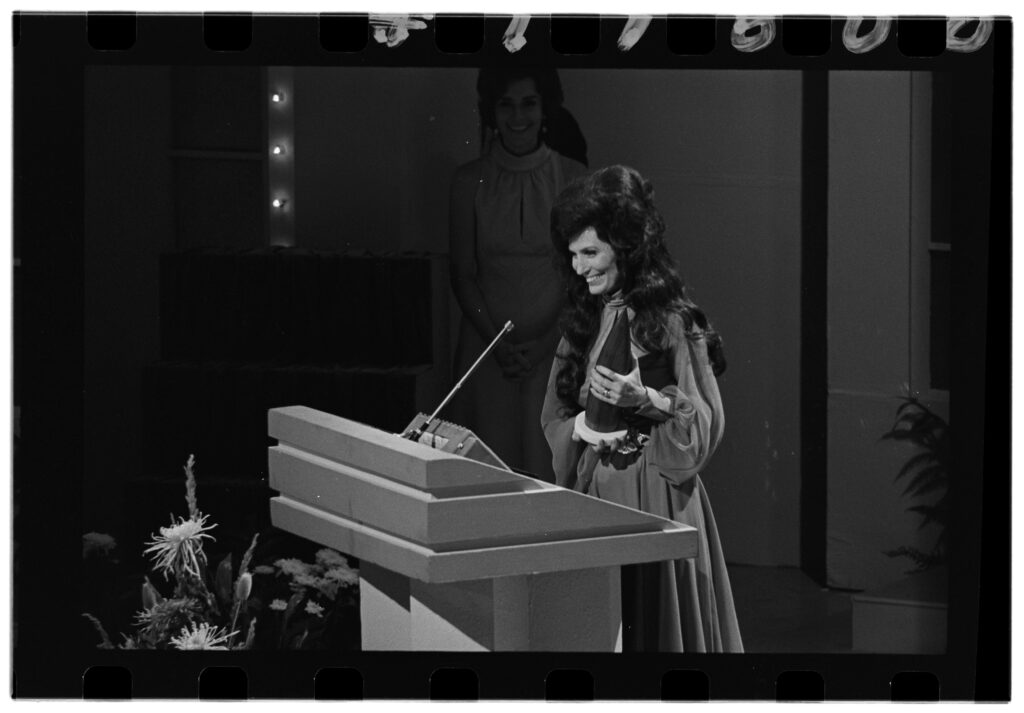

That history also leads us to ask not about the artists whose names show up on the award nomination list each year, but more interesting, the artists whose names are conspicuously missing. In 2024, media outlets are rife with stories about Beyoncé’s absence from the CMA nomination list, despite the success by almost every metric of her Cowboy Carter album and Beyoncé receiving Grammy nominations in every “country” category this year. Explanations vary, from the undeniable systemic racism in the country music industry, to gender discrimination (more on that below), to the always tense, usually defensive posturing by the country music industry against pop stars taking up space in the country music world. The industry’s, conservative stance about defining what “counts” as country music was, after all, one of the reasons why the CMA came into existence as an organization in the first place. Moreover, country music’s attention to the past also means it can really hold a grudge (the press has not let anyone forget that Beyoncé’s last intersection with the CMAs was on stage with The Chicks in 2016). The CMA awards also provide a window into the oft-discussed gender disparity in country music. When the CMA awards launched in 1967, no woman was on the ballot for Entertainer of the Year. That trend continued until Loretta Lynn finally appeared in 1971 and won a year later. Of the 50 nominations for that award in the first decade, only 14 percent went to female artists. Study after study has concluded in recent years that the country music industry, most especially format radio, makes almost no room for female artists, a fact that occasionally makes it into popular conversation as with the “tomato-gate” controversy in 2015, when a prominent radio consultant said that publicly. The Entertainer of the Year award is yet further evidence of that: each year the ballot has featured five artists, and in no year has there ever been more than two female artists on that list. Most years, it’s been only one, and for several stretches, such as 2002–2007, no female artists at all were nominated. It is simultaneously notable that, in 2024, the gender-neutral music categories of Entertainer, Single, Album, and New Artist of the Year have exactly one female entry each—leading to speculation about whether that is an effort to ensure some gender representation by way of a systematic nod, or if it is simply an even more glaring signal that the commercial mainstream country genre generally inhabits a male public persona.

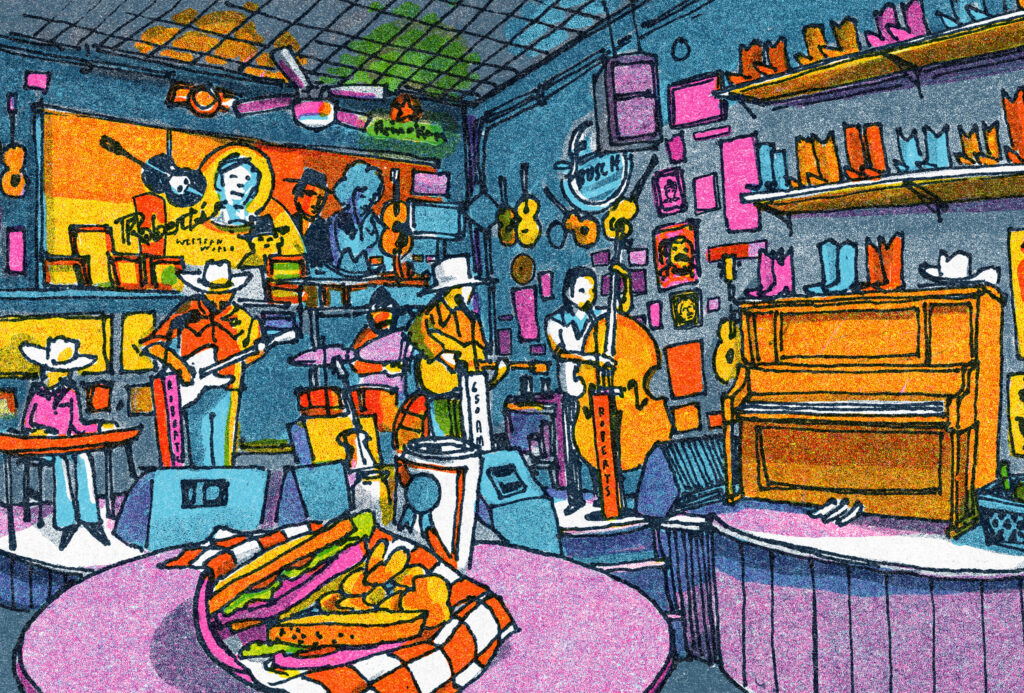

If the CMA nominations are one particular snapshot of country today, what might we listen for in that playlist? Still present are the age-old themes of nostalgia for an idyllic rural, agrarian-rooted existence, forgotten young love, and cowboys who can’t commit to a steady relationship (“Dirt Cheap,” “Watermelon Moonshine,” and “White Horse”); and anger and abjection in the face of broken relationships (“I Had Some Help,” “Burn It Down,”). The production values and musical styles on many of today’s recordings borrow unapologetically from pop trends and rely heavily on token individual instruments to serve as markers of country identity. And fans have remarked on the ubiquity of pop stars collaborating with country singers and showing up on the nominations list—a practice that is nothing new in country music. The dual tension between staying rooted in genre and branching out to connect with broader audiences goes all the way back to the artists who performed on the Grand Ole Opry in the 1930s, raising controversies over which ones were too pop to be considered country (such as the Vagabonds) versus which ones were too hillbilly to broaden the audience.

Despite the fevered pitch of politics in the air in 2024, country music remains largely divested from explicit discourse within the music itself. Certainly, individual stars, the rare virulent video, and the occasional viral song buck that trend, but for the most part, country songs skirt overtly political narratives, a symptom both of the genre’s deep populist roots and of the political diversity across the many different communities who create the music, most especially the songwriting community.

Ironically, the CMAs highlight not only music that has held sway over the radio airwaves in the past year, but also music that a country radio listener might not have encountered. Given how few female vocalists are prominently featured on radio playlists, the category of Female Vocalist of the Year often includes artists who have little to no radio presence. For instance, this year’s nominees include Kacey Musgraves, who has enjoyed plenty of commercial success, but the last time she had a single on Billboard’s “Country Airplay” chart was 2019. Ashley McBryde, similarly, has barely registered on the “Country Airplay” chart as a solo artist, but she has a fiercely loyal fan base among country fans outside of the mainstream radio-centered sphere, and has been nominated for a CMA every year since 2021. These cases offer a window into the ever-present tension between the narrow segment of country music featured on mainstream country radio and the far broader landscape of country music that exists beyond that medium. Sometimes tagged as alt, traditional, or singer-songwriter (among many other terms), these musical scenes play important roles in the long career cycles of artists and form a broad foundation of the genre.

The CMA nominations remain starkly white, with a few exceptions, notably Shaboozy and the duo War and Treaty. The broader public narrative about country music has reckoned with the music’s present-day whiteness in the past few years, from academic books on the subject to public podcasts (Rissi Palmer’s “Color Me Country”) and some noteworthy success by artists of color (Mickey Guyton, Kane Brown). Nonetheless, the CMA line-up suggests an entrenchment and oblivious stance that no listener should overlook.

Finally, two distinct categories, both of which consist of a list of song titles, highlight another interesting perspective for country listeners: Single of the Year and Song of the Year. Country music thrives on the notion of a great song, essentially lyrics, melody, and a chord progression, with a particular storyline and form. Country music fans have always lavished attention on the songwriting traditions and communities and think of the song as an essential commodity in the genre. In our listening experience, however, we hear those songs through particular performances: the creative output of musicians, producers, and audio engineers. Both intellectual property law and listeners’ experiences treat the two entities (song and recording) as distinct; Song of the Year focuses on the underlying song, while Single of the Year, on the other hand, focuses on the sound recording that uses the “song” as its starting point. In today’s musical world, however, many (but not all) artists are co-writers of their songs, and producers are frequently credited as songwriters, a trend that acknowledges how contemporary music production involves the creation of new musical material and blurs the conventional distinction between the two entities. Songs nominated in both categories such as “White Horse,” invite multiple listenings to tease out the distinctions between the song and the recording, and to appreciate how to the two sometimes get tangled up together.

Each year at the awards shows, the presenters and artists go to great lengths to convince their audience that the music is new, fresh, and exciting, laced with pop-star duets and sophisticated studio production. At the same time, they beg audiences to recognize the genre’s connections to its past and its investment in tradition to differentiate it from the larger world of pop music. But mostly, perhaps they steer our attention toward a particular narrative of country music that is still tied to radio-dissemination and governed by industry-gatekeeping. The overall goal is largely to defend country music against assimilation while simultaneously promoting it to new listeners. It’s a tight-rope act that occasionally backfires, as the awards show producers seek to expand their audience while at the same time promising country music’s loyalists that the industry stands as a seawall against the rising tides of genre-blending and crossover. It’s a nearly impossible challenge, just as it has always been, but the results make for some very interesting listening.

“Country’s Cool Again”:

An SC Music Reader

Fifteen essays, old and new, curated by Amanda Matínez. Read the full collection >>

Jocelyn R. Neal is professor of music, adjunct professor of American Studies, and chair of the department of music at UNC. She directs the UNC Bluegrass Initiative, and her research focuses on songwriting, American country music, and music analysis.

Header image: Cody Johnson, by Chris Hollo. Courtesy of the Grand Ole Opry Archives.