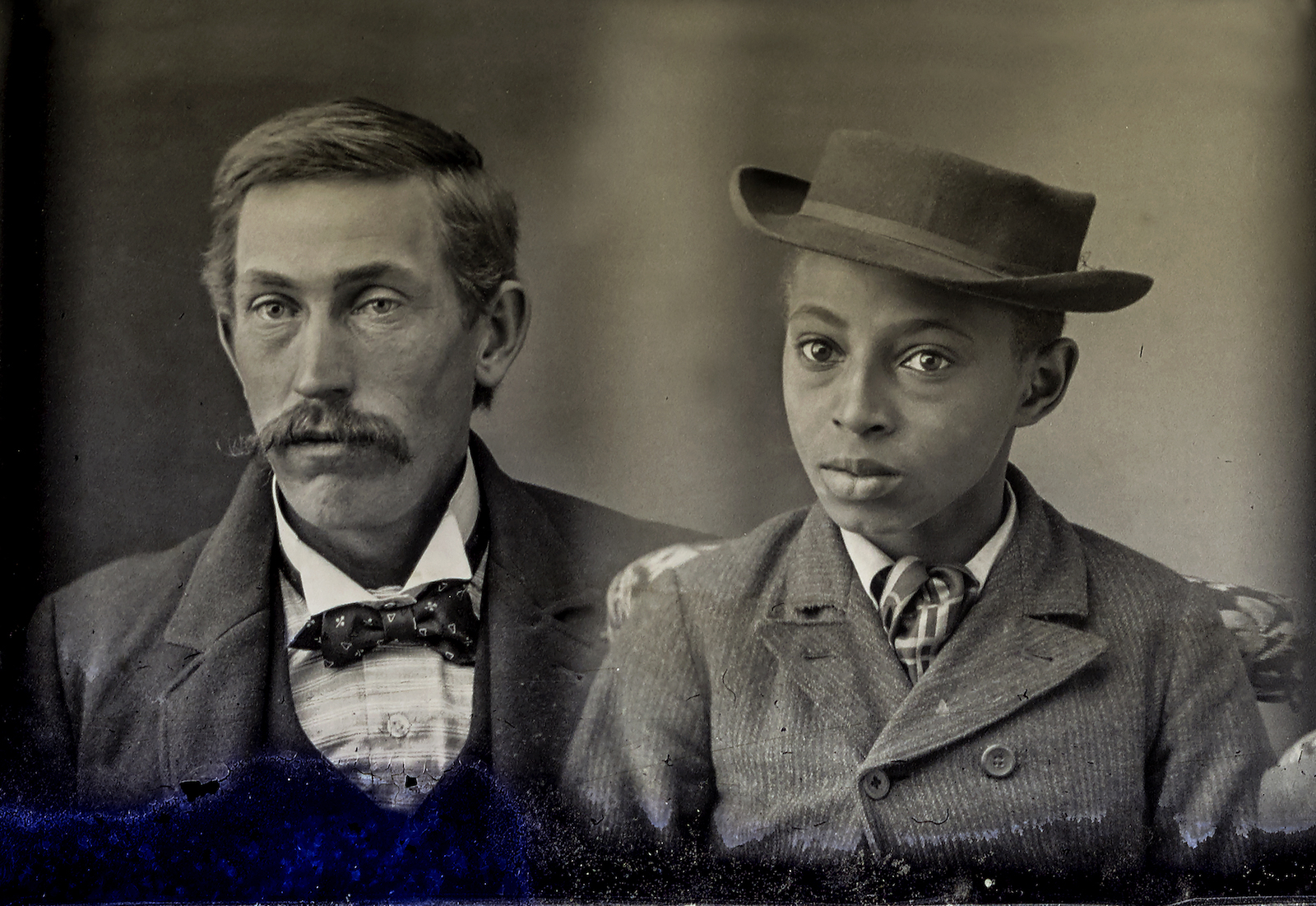

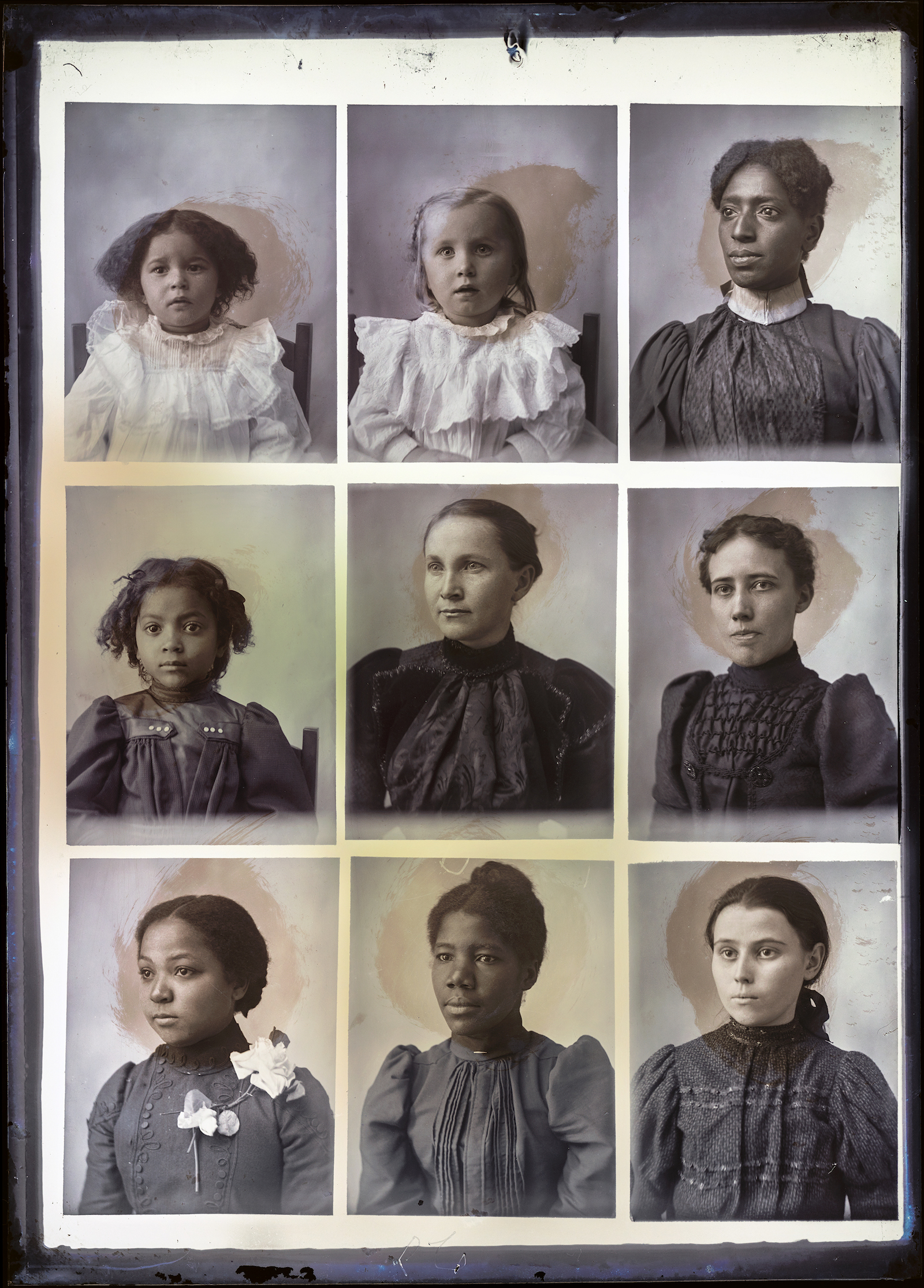

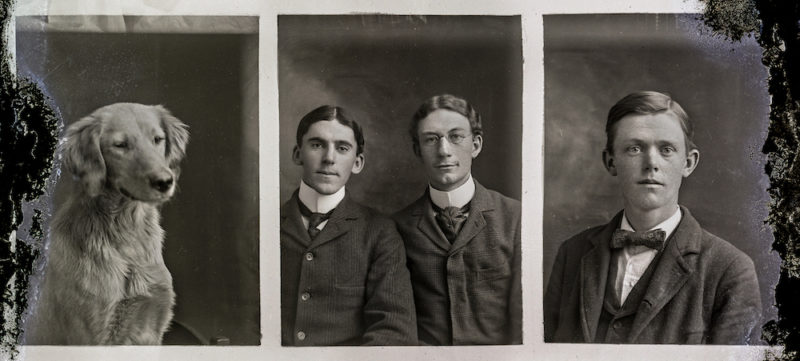

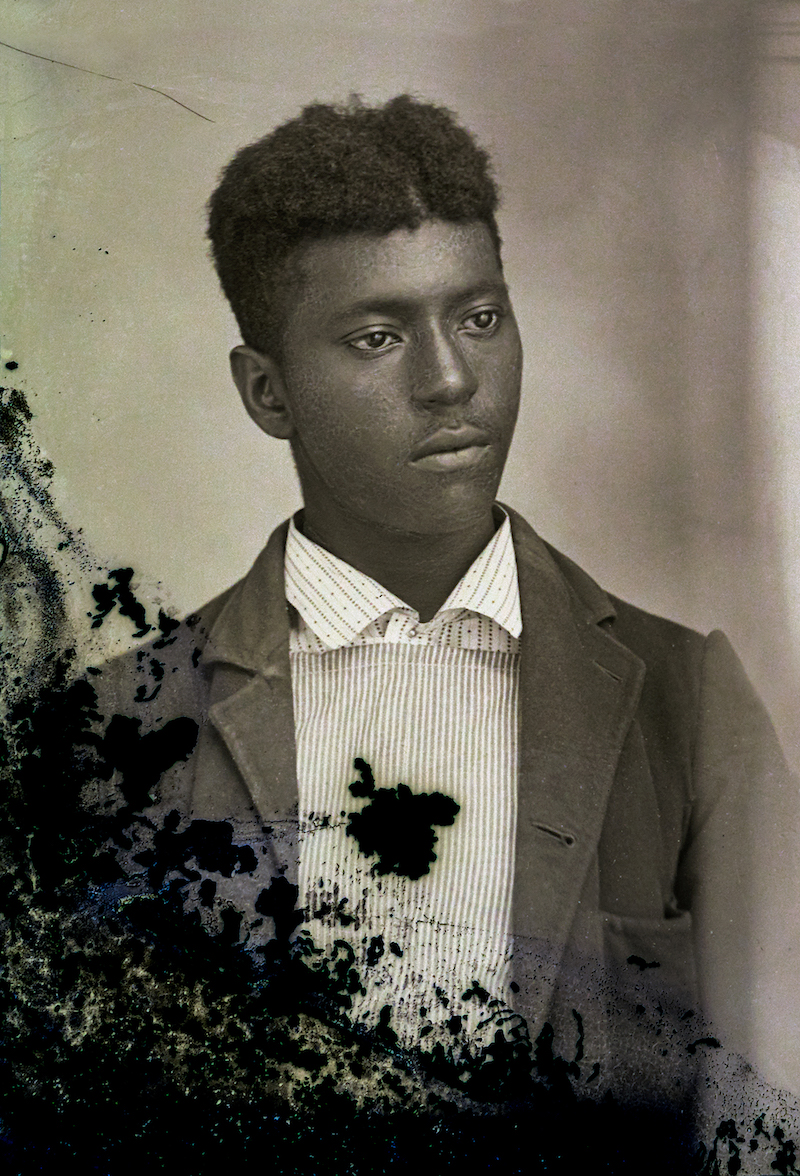

In the late 1890s, self-taught photographer Hugh Mangum (1877–1922) began riding the rails as an itinerant portraitist, traveling primarily in North Carolina and Virginia. Mangum worked during the rise of the segregationist laws of the Jim Crow era. Despite this, his portraits reveal a clientele that was both racially and economically diverse, and show lives marked by notable affluence and hard work, all imbued with a strong sense of individuality and self-creation.

One of the profound surprises of Mangum’s photography is its artistic freshness. He had a charm and curiosity that is often reflected in the faces of his sitters. In other images, Mangum’s presence as a photographer is invisible and the sitters appear lost in their own private, interior worlds. Mangum’s ability to capture these moments of vulnerability and intense self-recognition lies at the heart of his gift as a photographer.

From his travel log, we know that Mangum consistently returned to Durham, North Carolina, every few months to use his darkroom and store his accumulating glass plate negatives. When in Durham, Mangum set up his Cottage Studio in a tent or temporary space near downtown and announced his location, along with his opening and closing dates, on printed broadsides. Some of these broadsides survived, stacked among his glass plate negatives. They promote “All Kinds of Pictures” and “Specials to School Children.” “Come at once,” he urged in underlined letters, “and avoid the rush” (105).

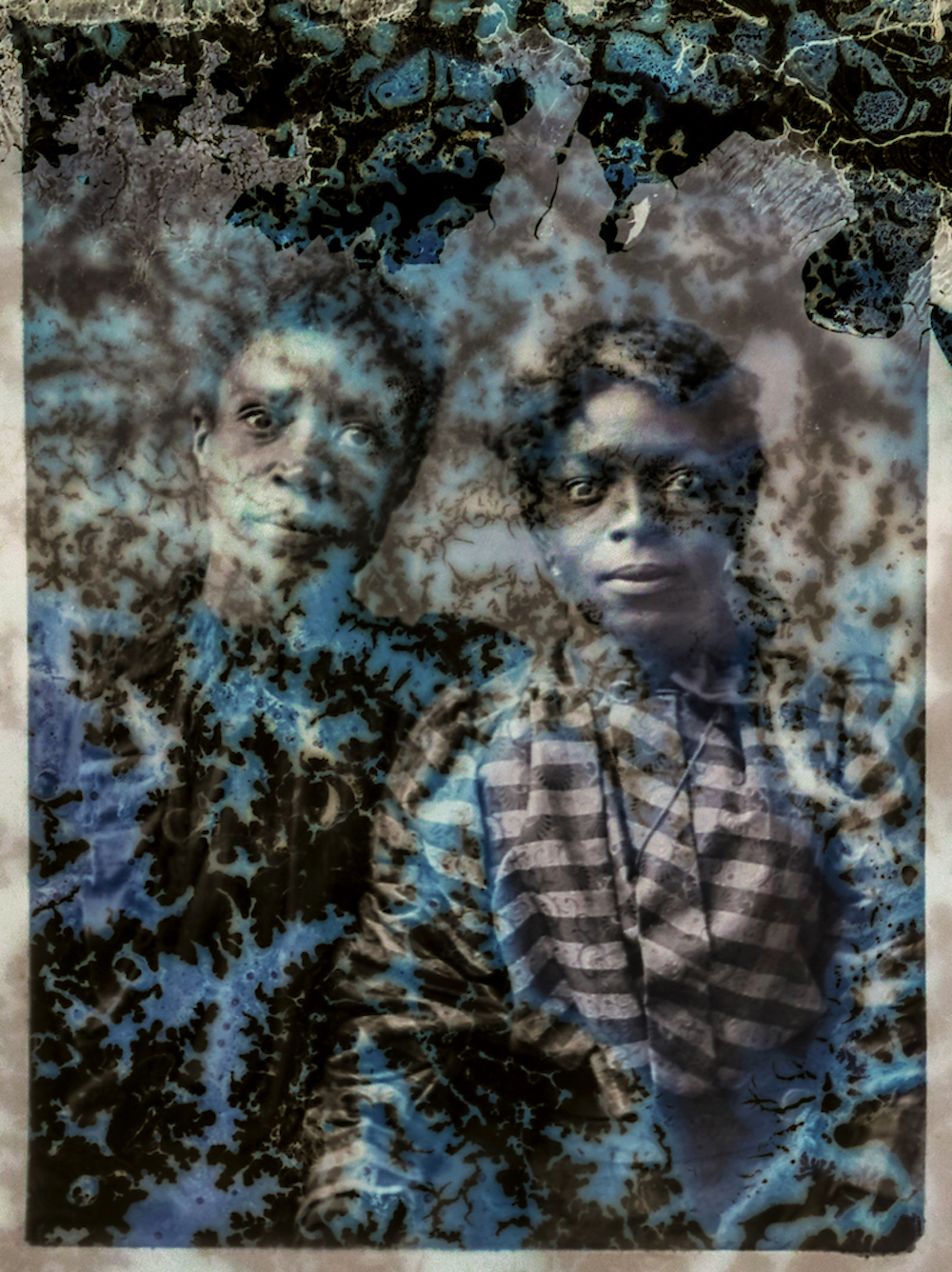

After his unexpected death in 1922, hundreds of Mangum’s negatives remained in a barn on his family’s farm, ignored but not discarded. Slated for demolition in the 1970s, the barn was saved at the last moment and, with it, this surprising and unparalleled document of life during a turbulent time in the history of the southern United States. His glass plate negatives are not only images, they are objects that have survived a history of their own and exist within a larger political and cultural history. They hint at unexpected relationships and complex lines of connection that refute the racial categories defined by law to separate black and white people. And though Mangum left behind no records to help us identify his sitters, the gaps in our understanding lead us to consider more carefully what we know, or what we think we know, confirming how early photographs have the power to subvert common historical narratives.

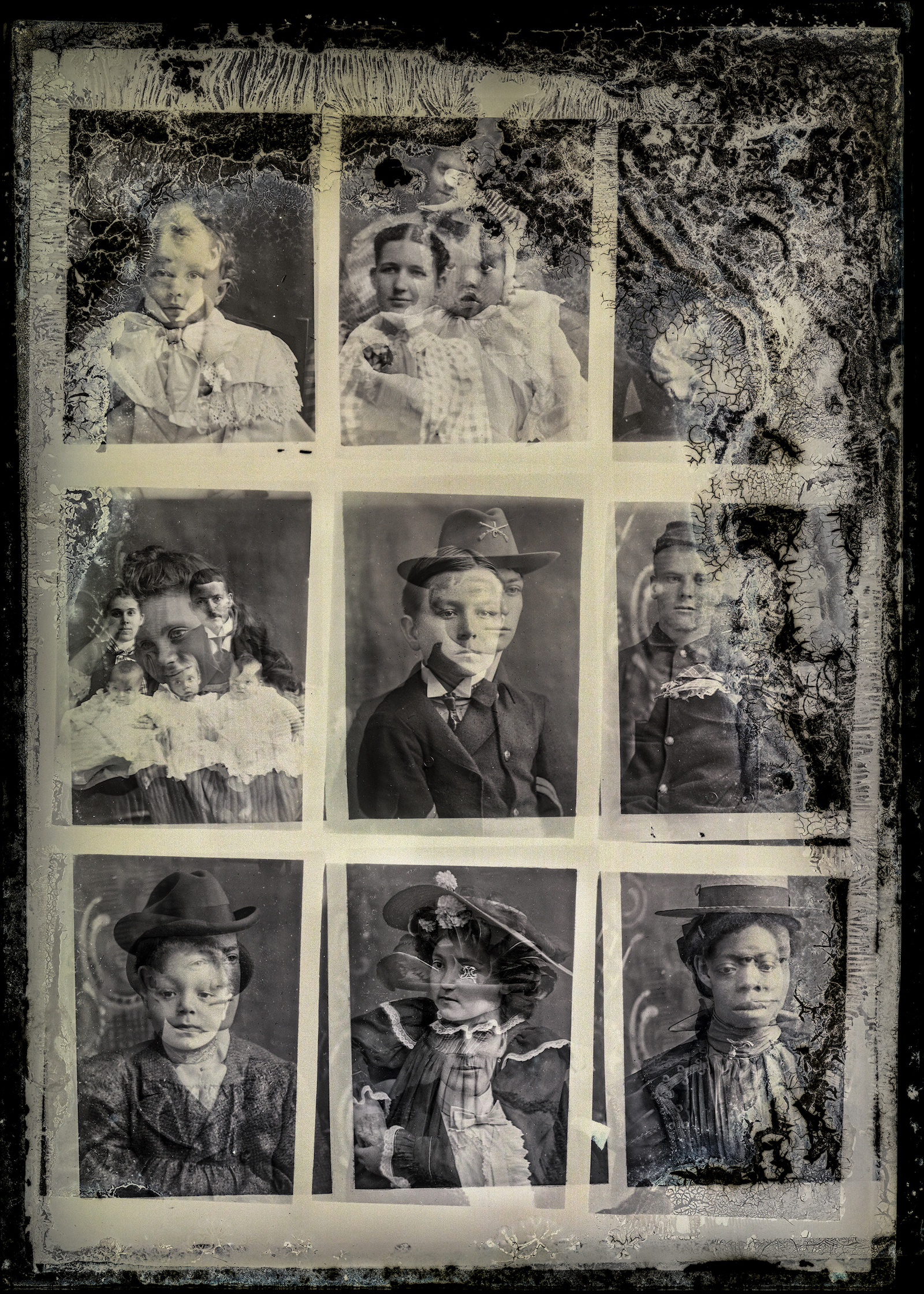

The original negatives, with all their damage and decay, reveal vibrant portraits of forgotten individuals. With the aid of twenty-first-century digital technology, Where We Find Ourselves reproduces Mangum’s black-and-white glass plate negatives in full color so that the scratches, cracks, fingerprints, and delicate color shifts that surround and sometimes cover the sitters’ faces give them new meaning. They also suggest that the distance between the past and the present is closer than imagined. Taken more than a century ago, Mangum’s photographic portraits demonstrate the unpredictable alchemy that often characterizes the most enduring art—its ability to evolve with and absorb life and meaning beyond the intentions or expectations of the artist.

In the newly incorporated, tobacco-fueled boomtown of Durham, North Carolina, Mangum began his nomadic career well after the heyday of traveling studios and just as the role of the professional photographer was being supplanted by the amateur. (In the 1880s, Kodak introduced its line of box cameras with the slogan “you press the button, we do the rest.”) But Mangum’s hometown was prosperous and would have provided a dependable client base for a portrait studio. So why did he choose to endure the unreliable income, the need to move cumbersome equipment from town to town, and the unending task of drumming up new business? What was it that Mangum could do as an itinerant photographer that he would not have been able to do by operating a permanent studio in one place?

One imagines that his chosen way of working satisfied a certain wanderlust and intense curiosity about people, but his motivation may have also been the opportunity to attract a wide variety of sitters, some of whom would have been unwilling to sit for a portrait if it meant climbing the stairs to a reception area and writing down their names—if they could write—in a record book. In 1900, more than 30 percent of North Carolina residents were illiterate (114). Only by being itinerant could Mangum pursue a way of working in which he did not have to depend, as most portrait studios did, on the wealthy and elite. Instead, Mangum decided to take his camera into the streets, so to speak, to the people, to make affordable portraits where and when he wanted. And by moving from town to town and working out of temporary spaces, he would have been less answerable to local customs or segregationist laws and ordinances, allowing him more freedom to relate to his sitters on both his terms and their own.

Yet part of what makes the negatives such an extraordinary contribution to the historical record rests not with his skill as a portraitist, but with his choice of equipment. For his itinerant work, Mangum used a Penny Picture camera—a small and somewhat rare view camera—placed on a tripod and equipped with modified backs that allowed him to record multiple exposures on a single glass plate negative. The modified backs, which held the glass plate negative, could be made to slide both vertically and horizontally behind the lens, so that, through a step-and-repeat process, a photographer could record images in rows and columns, creating a grid-like pattern of separate portraits. Mangum used a variety of Penny Picture backs, some of them homemade. Depending on which combination of backs he chose, he could make anywhere from one to thirty separate exposures in varying arrangements and in different sizes. The smallest possible image was the size of a penny, hence the camera’s name.

The aggregate of these multiple-image plates provides us with an unintended record—one both hopeful and radical in its implications—of the succession of sitters who passed through Mangum’s traveling studio during any given day, hour, or afternoon. We can literally see the procession of Mangum’s customers. And whether random or planned, looking at their faces recorded side by side makes it easier to speculate about connections between sitters that would be impossible if we viewed them only in individual photographs.

From here, we can only guess at the shape of lives lived together in one relatively small place. We can’t know for certain how lives were lived in the aftermath of centuries of human slavery. We can only infer how people interacted with each other in Mangum’s studio or within his outdoor setups. Part of the mystery and loveliness of these images is precisely that boundary between what we know and what we can only imagine or hope. Mangum’s portraits seem to show us truths implicit in interrelatedness, truths we can’t fully decipher. Historians may work to clarify the complicated history of race in this country, but only artists, like Mangum, can give us something, like these portraits, with the capacity to embrace and communicate the paradoxes within and disturbing ambiguities of this difficult and not-so-distant past.

This essay appears in the Here/Away Issue (Vol. 25, No. 4: Winter 2019).

MARGARET SARTOR is a writer, photographer, and curator based in Durham, North Carolina. She is the author of seven books, including Dream of a House: The Passions and Preoccupations of Reynolds Price (with Alex Harris); her best-selling memoir, Miss American Pie: A Diary of Love, Loss, and Growing Up in the 1970s; and the critically acclaimed What Was True: The Photographs and Notebooks of William Gedney (with Geoff Dyer). She has taught at the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University since 1991.

Editor’s Note: This essay has been adapted from the book Where We Find Ourselves: The Photographs of Hugh Mangum, 1897–1922, edited by Margaret Sartor and Alex Harris (UNC Press in association with the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University, 2019).