On the occasion of my retirement from the University of Mississippi in 2014, I knew I had to talk about the South, the topic I have spent my career studying, pondering, writing about, and teaching. The more I thought about what to present in a final, university-wide lecture, my personal journey seemed relevant, for I think my family and personal stories parallel some developments in the South’s history. My roots and raising were in middle Tennessee, as part of a very close-knit southern family. My parents were from small towns in tobacco country north of Nashville. They were what historians would call the “plain folk”—not wealthy, not the stereotypical poor whites, but, in my father’s case at least, poor in worldly goods as a child. My father’s people were burdened with a hardscrabble life as tenant farmers. My mother’s life was more sheltered, growing up in the small town of Springfield, near the Kentucky border. Neither had traveled farther than Nashville, but that changed when the United States entered World War II. Their story was typical of so many southerners of the early twentieth century, and the Great Depression of the 1930s was a particularly hard context in which to grow up. Many historians would now say that World War II had a greater impact on changing the South than even the Civil War did. My father joined the new Army Air Force and was stationed for three years in Bassingbourn, England. One of the most important themes in the study of the South now is globalization, and my father was part of that early on, in his uprooting from rural, farm Tennessee to be sent halfway across the globe.

After the war ended in the spring of 1945, my dad came home, and he and my mom married within a few months, and moved to Nashville, becoming a part of the postwar migration of southerners to cities and towns. The 1960 census was the first one in which more southerners lived in cities than in rural areas, and my family’s experience reflected that change. I was born in Nashville, but when I was nine years old, in 1957, we left Tennessee to move to El Paso, Texas, a move occasioned by my mother’s worsening health in the wet and humid Southeast. So we went west, going on Highway 80, shortly after which the federal government built what’s now called the Eisenhower Interstate Highway system. That program would tie the nation together in productive ways, and one result was bringing the South more directly into connection with the rest of the nation. That interstate highway system was a tangible expression of one of the most important factors in modernizing the South and making life better for our people, namely, the investment the federal government made in sending a disproportionate amount of federal tax money to the South to stimulate economic development.

In any event, this uprooting severed me from an extended kin of grandparents, aunts and uncles, and cousins, but it bound me even closer to my nuclear family. We had joined the movement to the Sunbelt, that term coined in the 1980s to reflect the South’s close ties to the Southwest, stretching to southern California. I grew up in a very cosmopolitan, suburban place—El Paso, a city with a mobile military population, high tech researchers associated with the defense industry, and strong cultural influences from southern California (my high school was just like that one in American Graffiti). And I was amidst an intriguing Anglo–Hispanic culture of a Mexican border town. In those days, it was a free-flowing border where we went across to Juarez to shop, eat, get our haircut, and buy gas—everything was less expensive there. El Paso itself, with its large Latino population, was somewhat exotic for a young Tennessean. I discovered I was a southerner playing with kids named Jesus and Juan on the playgrounds. I remember going to a birthday party at my friend Juan’s house, a colorful place for a child, and for the first time I saw a piñata. The tradition is the blindfolded child swings a stick trying to hit the piñata and when you do so, candy and toys fall out for the taking. I took the blindfold off, looked at all the treats, and thought, “Where have they been hiding this from me?” Suffice to say, I took to Hispanic culture, and I was ahead of the curve in terms of understanding the significance of the Latino migration to the South when it happened after I came to Oxford. When I moved there in the early 1980s, there were no Mexican restaurants, no Mexican beverages. I used to buy fresh tortillas in Texas and bring them back as carry-on luggage.

I discovered I was a southerner playing with kids named Jesus and Juan on the playgrounds.

The move to the Southwest had created opportunities for my family, and one of the lessons I learned from that move was an openness to change, to seizing opportunities when they arise. The move took us out of the comfort zone of our Tennessee home, but my family found ways to keep the family connection. Each summer my mother, my brother, and I would return to Greenbrier, Tennessee, where our grandparents lived and where we had that small town South experience. The rest of the year, my mother and her mother would write a letter to each other every day (no texting or email in those days), reviewing often the mundane or sometimes exciting events of the day. Change does not have to mean a severing of connections, just new ways to find to connect.

I have been using the word “southerner” to describe myself and my family members, but that is in retrospect. I do not remember my parents calling themselves southerners. They were very self-conscious of being from Tennessee, and my mother wrote poems about the state and her feelings for it. But we were not self-consciously southern in those days. They told no family stories of the Confederacy, and they taught us no racial obsessions nor self-conscious white identity. Like all white southern families, mine benefited from a way of life that gave whites opportunities denied to African Americans. But my family could not afford the legendary “help,” and my brother and I were the yardmen, not the African American man seeking work. Somewhere along the lines, though, I realized we were southern in culture. We attended the same church denomination we had in Tennessee, my mother cooked fried chicken and pork chops and sweet potatoes as her mother before her, my brother and I heard our mother singing religious songs, and we listened to country music as the good Nashvillians we had once been.

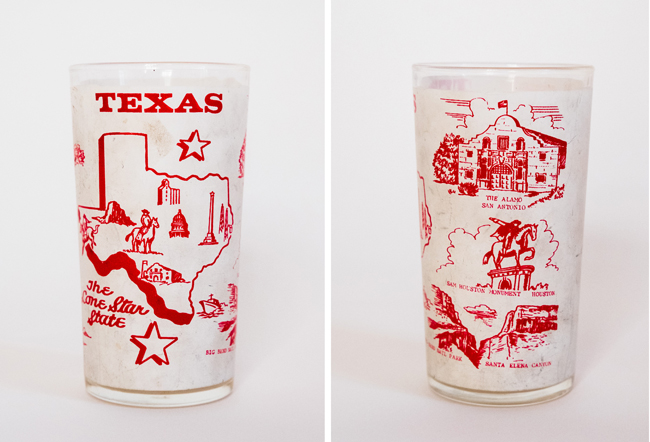

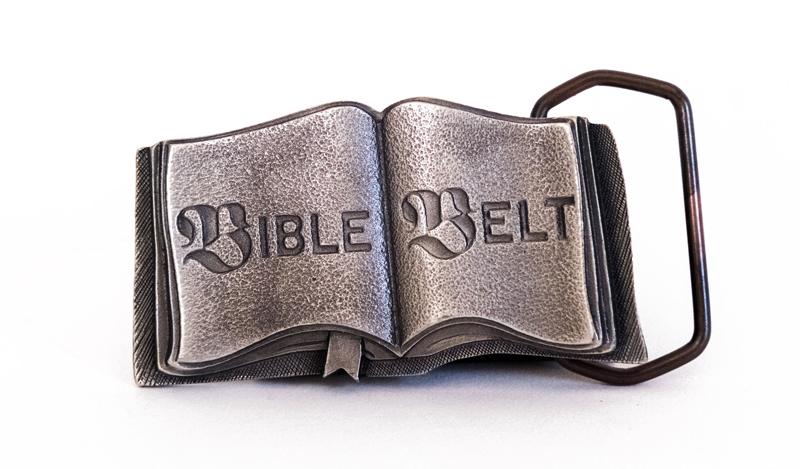

That visceral appreciation of the importance of culture to southern identity served me well when I came to Oxford in 1981 to be one of the editors of the Encyclopedia of Southern Culture, work on which, through two editions, has been a focus for my over thirty years at the University. When I arrived in Oxford, you could still see hints of the older South. There were still two hardware stores on the Square, as there once were in small towns. I knew Oxford was changing when both hardware stores left the Square, and a boutique named Chantilly Lace opened where one of them had been. At that time, the University only had about 7,000 students, and the three antebellum buildings had not yet been renovated and were in a noticeable state of decline. The Center for the Study of Southern Culture had only recently begun its work, and it soon launched or supported innovative projects including an undergraduate curriculum, conferences and workshops, magazines and newsletters, and scores of other activities. When I began teaching my course on southern religious history, the enrollments were relatively high. History department chair Bob Haws suggested that students thought they were signing up for a devotional hour. Nonetheless, the course was part of the history department and Southern Studies commitment to teaching and researching about the South—to “tell about the South,” as Oxford’s own Mr. Faulkner wrote. My interest in popular culture led me to become a collector of souvenirs of the South, those mass-produced, curious knick-knacks that relate to southern culture, which I often used in teaching and public presentations to illustrate points about the South. They are kitsch, but someone gave them a term out of southern vernacular—southern tacky.

The Lure of Southern Tacky

I first felt the lure of southern tacky in childhood. Each summer, our 3,000 or so round-trip miles between El Paso and Nashville presented many possibilities for gifts from the road. Frontier-village amusement parks, tourist meccas like Six Flags Over Texas, animal farms with snakes and alligators—each had a souvenir to buy and save. And how many times did we stop at Stuckey’s, a once-vibrant roadside store with a wealth of tacky—plastic armadillos, cedar plaques praising Moms and Dads in rhyme, and an impressive quantity and variety of salt-and-pepper shakers.

My half-formed interest in southern tacky lay dormant for years, but when I began work on the Encyclopedia of Southern Culture, I started to look at such artifacts anew. Perhaps I needed the whimsy of having a mosquito fashioned from seashells on my desk or a pink flamingo toothpick dispenser to counter-balance the scholarly responsibility of preparing a weighty reference book. Whatever the reason, in my reborn passion I came to realize that mass-produced objects regarded by people with “good taste” as being in “poor taste” featured an explicit southern dimension worth pondering. I collect southern tacky because these artifacts stir meaningful associations for me. They may be souvenirs of a theme park, resort, or historic spot; they may be mementos of a political campaign or a religious retreat or the everyday lives of our ancestors. Often they overtly portray the region’s icons—the Bear Bryant Coca-Cola bottle, magnolia paintings for Mississippians, bluebonnets for Texans, or Confederate generals on a Stone Mountain paperweight.

Perhaps I needed the whimsy of having a mosquito fashioned from seashells on my desk or a pink flamingo toothpick dispenser to counter-balance the scholarly responsibility of preparing a weighty reference book.

Spurred to research, I discovered that southern tacky actually has a history. It dates from the late nineteenth century, when admirers of the Confederacy created an iconography of Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, and Stonewall Jackson. Manufacturers placed their images on prints, knives, whiskey bottles, sacks of flour, decks of cards, and innumerable other objects. A century later, southern tacky remains tied to popular culture. Likenesses of celebrities of music, literature, film, and television appear on postcards, buttons, pins, ties, shoestrings, and matchboxes. Dolly Parton, Richard Petty, Jackie Robinson, Jerry Lee Lewis, Andy Griffith, Dr. Martin Luther King—all are familiar images.

The king of southern tacky, though, has to be Elvis. His life itself embodied the phenomenon. Born into a poor family, Presley developed an aesthetic of flashy colors, opulence, and sensuality that appealed to the fantasies of many rural southerners. His ideal must continue to fascinate, too, for his image adorns countless artifacts to this day. My favorite is a card marketing “Elvis’s Sweat.” Boasting a close-up of Presley’s face, the card—all bright yellow and blue and pink—proclaims: “The impossible has happened! Elvis poured out his soul for you and NOW you can let his PERSPIRATION be an INSPIRATION.” Attached to the front of the card is a small vial of liquid. (I have never actually opened this relic, fearing its power.) Now, this object has a cleverness and originality, yet it was mass-produced. I have no idea if it is serious or just plain awful, but I know it has a certain soulfulness and humor.

The king of southern tacky, though, has to be Elvis. His life itself embodied the phenomenon.

Not every southern souvenir is so playful, though. I collect old church fans and they touch something different and reflect very real religious concerns. These fans, like other material expressions of southern culture, were cheap to make, easy to distribute, and qualify as ephemera in our modern life. But I’ve learned they are important expressions of everyday life, of ordinary time. Writer James Agee in his classic book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men wrote of the majesty of looking closely at the ordinary in southern life, in the simple objects of a household collected by southerners who often had hard lives. Agee was thinking mostly of folkways, but in the modern and postmodern worlds mass-produced artifacts reflect something of southern pleasures, aspirations, and humor. Southern stuff is a material expression of southern identity, a topic that has been at the forefront of my generation of scholars’ efforts to find lessons about the South. My collection of southern stuff is in Barnard Observatory, the historic antebellum house that houses the Center for the Study of Southern Culture. It likely will be there a long time, as my wife does not share my fascination with southern tacky, and the collection will probably not wind up at home.

In the modern and postmodern worlds mass-produced artifacts reflect something of southern pleasures, aspirations, and humor.

Locating “the South” Takes More Than a Map

Regions like the South or the West or New England are geographical areas that because of long histories, cultural practices, and ideas associated with them take on meaning as places of identity. They produce social groups that associate themselves with the spaces of a region. In modern times, we all carry around many identities in our heads: I’m an American, a historian, a professor. I’m a member of a religious group. Like many people in the South, I also think of myself as a southerner. People have identities based around being members of social clubs, voluntary groups, or sports teams, among other activities. Not everyone who lives in a region comes to claim that regional identity, of course. I have a friend who was born in Nebraska, went to college and graduate school at the University of Nebraska. Despite living and teaching in Mississippi for over forty years, he’ll always been a Cornhusker.

It has long been assumed that national and regional identities were enduring, essential, and unchanging, and generalizations were made about them. A Polish proverb says, “What the Italian invents, the Frenchman makes, the German sells, the Pole buys, and the Russian takes it from him. Mark Twain observed: “One speaks of FRENCH vivacity and GERMAN gravity and ENGLISH stubbornness. There is no American temperament. The nearest that one can come at it is to say there are two—the composed NORTHERN and the impetuous SOUTHERN; and both are found in other countries.” (The only unifying American characteristic, according to Twain, was “the national devotion of ice water.” And we might add, iced tea in the South.)

The creation of the South, real and imagined, came from a long process of historical change and cultural practices, and its meanings change from group to group and person to person.

Twain was witty as ever, but he was dealing humorously with what we now know are stereotypes. Scholars have shown that regions like the South are socially constructed ideas, producing stereotypes, positive and negative, with meanings that evolve. They are contingent on changing circumstances and are inherently unstable, full of possibilities for change even while preserving continuities. The creation of the South, real and imagined, came from a long process of historical change and cultural practices, and its meanings change from group to group and person to person. The Mississippi Delta is one South, Piedmont North Carolina another, and the Appalachian South yet another still. There are many Souths and many southerners. Being southern is learned behavior and that varies from place to place in the region.

Defining the South itself must take into account the varieties of southern experiences. “The South” appears at times, for example, as a historical term—the eleven states of the former Confederacy. But Kentucky and Missouri were slave states in 1861, shared many customs and attitudes with people farther south, and, hey, we play them in athletics because they are in the SEC. The U.S. Census Bureau classifies the South as the former Confederate states, plus Maryland, Kentucky, Oklahoma, Delaware, and Washington, D.C. For the federal government to place the nation’s capital inside the South, which once rebelled militarily against it, seems a bureaucrat’s irony, but it again illustrates that locating “the South” takes more than a map.

Virginia is southern at its historical sites, but in places near Washington it is also a part of the northeastern megalopolis. How does the world of south Florida fit into a South identified with moonlight and magnolias, or moonshine, for that matter? Where is the dividing line between East Texas and West Texas, between “southern” and “western” spheres? Writer Willie Morris once told me that one Texan he met knew exactly where that line was—Conroe, Texas—because west of that small central Texas town bar fights were indoors and east of Conroe bar fights were outdoors.

From ’Cue to Kibbee

The South can be seen as a collection of regions. The Appalachians, the Alleghenies, the Blue Ridge, and the Ozarks are the Mountain South. The Upland South has been a place of hill country farmers, the tobacco business, and textile mills. The Lowland South is the Deep South, a place of cotton growing, the blues, warm Gulf Coast breezes, Florida beaches, and Latin rhythms. The urban South has been the center of each New South since the late nineteenth century. One could chart more specific landscapes in Cajun Louisiana, the Kentucky bluegrass, the Mississippi Delta, and the Piney Woods.

Each place is defined culturally by its food as well as its terrain.1 Barbecue provides a classic example. All southern regions can affirm the importance of this gift of King Hog. North Carolinians cook it so long that it falls apart, and they insist on serving it shredded on hamburger buns. South-central Kentucky restaurants often serve slices of pork shoulder as barbecue with bones in, dipped in sauce, and accompanied by white bread. Texans barbecue sausage links, a practice that dates from German settlement in the nineteenth century. Sometimes barbecue is not even pork. Those same Texans barbecue beef brisket in tribute to the cows that have been a part of their way of life for so long, some Kentuckians feast on mutton barbecue, and Latinos have encouraged the rest of us to enjoy barbecued goat.

Foodways also demonstrate the way ethnic identities become intertwined with regional identities. Eli Evans, in chronicling the story of Jewish southerners, told of the young Alabama man who remembered his mother serving “kosher grits,” a good emblem in memory of his self-consciousness. When I was in school in central Texas, I remember going to Oktoberfest in New Braunfels, which had been settled by Germans in the nineteenth century. I bought a German sausage that had been wrapped in a tortilla and put on a stick—a southwestern eclecticism that I probably would not have found in Munich.

One of my favorite family memories is of my wife’s family, the Antoons, who are from Greenwood. They are Lebanese by ancestry and have lived in Mississippi for generations. One Thanksgiving, my father-in-law Asper hosted more than forty relatives for a family reunion. His mother, Marie’s grandmother, known affectionately as “Big Mama,” even though she was no taller than five-foot-three, was in attendance and in good spirits at age ninety-four. My father-in-law fried Cajun turkeys—whole turkeys or turkey breasts cooked in sizzling peanut oil for less than an hour, coming out juicy on the inside because of a rich marinade and the hot oil sealing in the flavor. He and his nephew, who had come to Mississippi from Washington State for this event, also made kibbee, that wonderful Lebanese meat dish. We had stuffed grape leaves and cabbage rolls and baklava, reflecting the family’s heritage, but also oyster dressing and sweet potato casserole, which reflect their identity as southerners. The meal and the family embody much for me about the South: the diversity that belies the simple stereotypes of the region and the underlying cultural practices that shape all sorts of folks into southerners, and the South into many Souths.

Legacies and Futures

Any way you look at it, race relations has been a defining feature of the South. Our early economy came to rest on slave labor, and after emancipation, it rested on coerced labor and nurtured an oppressive society for African Americans. My history department predecessor, James Silver, wrote in the 1960s of Mississippi as a closed society, indicating the sometimes ruthless enforcement of racial orthodoxy. Thankfully, we have come a long way from those days, but we can’t let ourselves off the hook too easily. If our race relations look a lot like those in the rest of the nation, that’s faint praise. If the signs indicating “colored” and “white” no longer mark our landscapes, the divisions remain, more subtle and coded but still noticeable and deeply felt.

Moreover, our campus will always be burdened with the special responsibilities that came with the crisis over the admission of our first African American student, James Meredith, in 1962. It pains me that one lesson I have learned is that it is more difficult for some faculty to teach about the South than for others. I know from conversations with African American faculty that they sometimes face disrespect and hostility from students, making their teaching about the South all the more fraught. Former Mississippi governor William Winter reminds us that there have always been southerners who witnessed for civility in discussions with people with whom you might disagree. It’s a southern tradition, but only if we practice it. And we had a fraught year in 2014 because of the defacing of the James Meredith statue commemorating the integration of the university in 1963. The campus collectively experienced a cultural trauma that exposed deep doubts and anxieties about how far we have come. A theorist of cultural trauma writes that one possible outcome of trauma can be to mobilize human agency, which, through coping with trauma, can bring a rebirth, a force for social progress. Becoming something new. The optimist in me hopes this will be the case here. I was impressed with the student reaction to the incident, as student leaders across campus condemned the act, university-sponsored forums addressed the issues surrounding the event, and ad hoc student expressions expressed frustration that recent efforts at fostering racial reconciliation had failed to prevent another race-related incident.

We know that how we represent history can skew how we see the present. Whose history in whose South?

The defacing of the Meredith statue was not an isolated incident, but my optimism hopes it will be the trauma that forces our collective free will to say, “No more.” Looking into the future, perhaps this incident was so traumatic that it will be the turning point when our campus truly embraces the Meredith statue and the ideals of racial reconciliation that it represents. Given that no one publicly endorsed this vandalism, why do such incidents keep happening? Is there something in the culture here that has fostered a tolerance for symbols of racial antagonism? I fear we sometimes have a sanitized history. If we celebrate hoop skirts and colonels, we distort history in not acknowledging the slave quarters that tell the other side of the story, a story that informs our community equally. We know that how we represent history can skew how we see the present. Whose history in whose South?

But I remain hopeful, partly because I often learned from my students. That is one of the pleasures of being a professor, and this was so as I was thinking about this lecture. I was on a thesis committee for an Honors College student, Meagan Henry. Her wonderful thesis was on the Christian writer C. S. Lewis, and it was about the idea of transformations. It struck me that our campus continues to be in an on-going transformation from an older worldview to a newer one.

Meagan wrote of the need for “new stories and new experiences,” and that is what I have learned teaching about the South over a long time period. There are many ways to be southern, and we should affirm those that reflect our creativity and achievements, not our failures and defeats in the past. The dominant black–white paradigm has been a central factor in creating southern culture, although of course the South is, again, more complex than this binary may imply. Despite segregation, the South’s peoples have managed to interact over generations. Ours is the story of distinctive cultural groups—Natives, Europeans, and Africans—who created a new culture in the South. In the course of living together on southern soil for centuries, they maintained cultural traditions while exchanging cultural knowledge and blending their expressive traditions in creative ways. The South discovered you cannot segregate the eardrum. People with musical talents crossed racial lines to hear each other’s music and make use of it in making their own. Jimmie Rodgers heard African American singers on the railroad crews of Mississippi and then created the white blues as the father of country music. Hank Williams learned to play the guitar from a black street singer in Montgomery, and Ray Charles listened to country music growing up in Georgia, so it was no surprise when he chose to record a soulful country music album in the 1960s. Elvis Presley grew up poor, in a society that threw together whites and African Americans who shared economic deprivation and also their music, and the result from people like Elvis and Fats Domino and Chuck Berry and Carl Perkins and Little Richard was rock ’n’ roll.

The South discovered you could not segregate the palate. Barbecued ribs, fried chicken, grits, cornbread, okra, black-eyed peas—these went in a cauldron of racial amalgamation, in which meat and vegetables, recipes, and ways of cooking boiled down into a new stew distinctive to the South. Thinking of food reminds us that the southern story is not just a biracial story, as the Native Americans of the Southeast pioneered southern foodways, and not only that, but environmental knowledge, folk beliefs, transportation routes, and so many other cultural forms trace back to the Native peoples of the Southeast. Restoring the Indians to the center of southern history is a lesson I’ve learned in studying the region, and one that will continue to preoccupy scholars telling new stories, which in fact are old stories unacknowledged.

The southern saga is of peoples from dramatically different cultures trying to live together and build a better society. The story includes injustice and tragic moments, but it also reveals heroic struggle and the possibility of change and reconciliation.

And there is the crux of whose South it is. The diversity that has always been a part of southern life, the presence of peoples of a variety of cultural ways, has often not been acknowledged. There are many Souths and many southerners. The University of Mississippi and the state of Mississippi need to be in the forefront of the contemporary South’s struggles to affirm, to say yes, to its legacy. The South is no longer the home of nineteenth-century southerners; those of us who claim the southern identity are no longer twentieth-century southerners. We are twenty-first century southerners. As the United States and the rest of the Western world increasingly interact with peoples from many cultures from around the globe, the southern story will likely continue to resonate. The southern saga is of peoples from dramatically different cultures trying to live together and build a better society. The story includes injustice and tragic moments, but it also reveals heroic struggle and the possibility of change and reconciliation. Acknowledging the inclusive story of the southern past and present is a possibility that has to be a collaborative project, one that will require work to achieve. I have learned teaching about the South at the University of Mississippi that that is the South’s legacy to the world.

Whose South is it? It’s all of ours if we shoulder its burdens, embrace its complexities, appreciate its diversities, revel in its joyful noises and delightful flavors, and build on its history to forge a twenty-first century South.

This essay first appeared in the Winter 2016 issue (vol. 22, no. 4).

Charles Reagan Wilson was the Kelly Gene Cook Sr. Chair of History and Professor of Southern Studies at the University of Mississippi, where he taught from 1981–2014 and directed the Southern Studies Program (1991–1998) and the Center for the Study of Southern Culture (1998–2007). Wilson received his BA and MA from the University of Texas at El Paso and earned his PhD in history from the University of Texas at Austin. He is the author of Baptized in Blood: The Religion of the Lost Cause, 1865–1920 (1980), Judgment and Grace in Dixie: Southern Faiths from Faulkner to Elvis (1995), and Flashes of Southern Spirit: Meanings of the Spirit in the U. S. South (2011). He is coeditor (with Bill Ferris) of the Encyclopedia of Southern Culture (1989), general editor of the 24-volume New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture (2006–2013), and editor or coeditor of Religion and the American Civil War (1998), The New Regionalism (1996), and Religion in the South (1985).NOTES

This essay was originally presented as the University of Mississippi’s Last Lecture of the spring semester, delivered May 2, 2014, in the University’s Gertrude C. Ford Center. I want to thank all of my colleagues in the department of history and the Center for the Study of Southern Culture. I particularly want to thank the history department chairs, Fred Laurenzo, Bob Haws, and Joe Ward for their support. The Center’s founding director, Bill Ferris, and its long-time associate director, Ann Abadie, made the Center a stimulating and creative place, which continues under the direction of director Ted Ownby and associate directors Jimmy Thomas and Becca Walton.

- The following paragraphs draw from my “The South: Where, Who, and What’s for Dinner,” Introduction to A Gracious Plenty: Recipes and Recollections from the American South, ed. John T. Edge (New York: Berkeley Publishing Group, 1999), xiii–xvii.