In the United States, why is wealth—especially financial wealth—held by white households so disproportionately and, in particular, by the most affluent ones? Racial wealth inequality is no accident of history. Rather, it is the intended result of the southern Democrats in Congress who controlled federal tax policy throughout most of the twentieth century. Beginning in the 1930s, champions of white supremacy, such as Senator Pat Harrison (D-MI), Senator Walter George (D-GA), and Senator Harry F. Byrd Sr. (D-VA), turned to an ostensibly race-neutral provision of the US income tax code—the preferential treatment of gains from investment—to uphold their (im)moral economy of “whites-only” wealth. After 1965, these segregationists’ successors—particularly Senator Russell B. Long (D-LA) and Senator Lloyd Bentsen (D-TX)—furtively rebuilt and shored up the structure of racial inequality with additional tax breaks for investors. They erected a vast system of pro-investment “tax expenditures” that immortalized a Jim Crow–era moral economy of “whites-only” wealth.

Tax expenditures—which include deductions, exemptions, exclusions, credits, and reduced (called “preferential” or “preferred”) tax rates—reduce tax liabilities for activities or groups of taxpayers that policymakers aim to encourage or to reward. Tax expenditures that favor investment by households include (in order of size) exclusions for pensions and retirement savings, preferential (or reduced) tax rates on capital gains and dividends, the elimination of capital gains taxes on assets transferred at death, the exclusion of capital gains taxes on the sale of principal residences, and the mortgage interest deduction for owner-occupied homes. In 2019, according to the Congressional Budget Office, the highest quintile of earners in the United States received 63 percent of the benefits attributable to tax-free pensions and retirement savings, 95 percent of the benefits flowing from the capital gains tax preference, 56 percent of the exclusions for capital gains on inherited assets, 84 percent of the tax savings from the deduction of mortgage interest, and 44 percent of the amount households save due to the exclusion of capital gains taxes on the sale of primary residences. Taken all together, tax expenditures that encourage or reward investment by households will total $657 billion in 2022, equaling 49 percent of all federal income tax expenditures, according to Treasury Department data. A full 50 percent of the total benefits of all income tax expenditures accrued to households in the highest decile of the income distribution in 2019.1

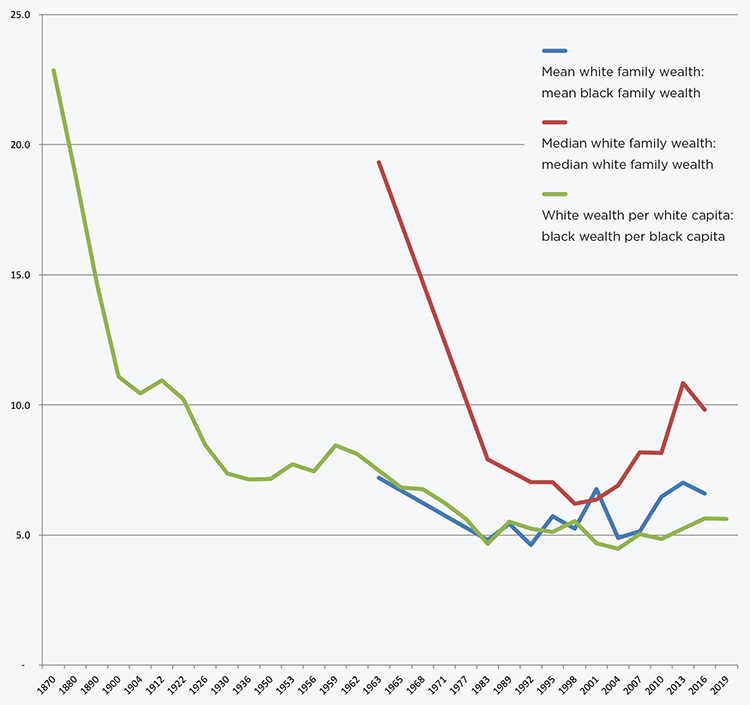

Pro-investment tax breaks appear neutral with respect to the race of the filer, but since the introduction of the first tax expenditure in 1921, they have favored the most affluent white households overwhelmingly. White families always have been far more likely to hold the type of assets—homes, stocks and bonds, retirement accounts—that tax expenditures reward. For every type of asset and across all assets, the median value of white families’ holdings always has been significantly greater than those of Black or Hispanic families. In every year since 1922, the wealthiest households—nearly all of them white—have earned the bulk of capital gains. In 2013, Black households received roughly 8 percent of the benefits attributable to tax-free contributions to pensions and retirement savings accounts, 5 percent of the benefits flowing from the capital gains tax preference, 7 percent of the exclusions for capital gains on assets transferred at death, and only 7 percent of the savings resulting from the deduction of mortgage interest. In 2019, nearly 30 percent of white families in the US reported ever receiving an inheritance or gift, compared to only 10 percent of Black families, according to the Federal Reserve. In 2020, the top 1 percent of earners received almost 80 percent of the benefits derived from tax breaks for long-term capital gains and qualified dividends. Within that top 1 percent, only 4 percent of households were Black.2

As the most expensive social commitment of the federal government, tax expenditures produce a “hidden welfare state” that skews heavily in favor of wealthy whites. Pro-investment tax expenditures allow affluent white families to keep more of their income after they pay taxes, as long as that income derives from—or flows into—investment. Those white households already rich enough to invest pay a lesser tax rate on their income and gains from investment (capital gains) than the tax rate levied on the “ordinary” or earned income of salaried and waged workers. The mortgage interest deduction and the exclusion of capital gains taxation on the sale of primary residences shields homeowners’ income and harbors their wealth, its accumulation quickened even further by tax-free contributions to pension and retirement accounts. Gifts and inheritances escape any taxation on the unrealized capital gains accrued during the lifetime of the benefactor. Parental wealth helps the children of affluent whites to avoid student debt, start a business, or buy a home. Over time and across generations, discrepancies in after-tax income harden into persistent racial wealth gaps.3

The US tax code cloaks in silence its contributions to the supremacy of white wealth and its transmission across generations. Even so, pro-investment tax expenditures embody, produce, and reproduce the moral economy of “whites-only” wealth that the southern Democrats who legislated these tax breaks, beginning in the 1930s, intended to secure and to convey. Over the next several decades, the proliferation of tax expenditures amounted to a long reactionary campaign to shore up the power of white wealth against recurrent challenges from progressive, Labor-Left, and civil rights movements. When the Revenue Act of 1978 slashed capital gains taxes to pre–New Deal levels, it marked the emergence of the bipartisan neoliberal policy consensus that has reigned ever since. In the decades that followed, the racial wealth gap widened as the very richest American households—the white 1 percent—enlarged their share of household income and wealth, at the expense of everyone else.

The New Deal vs. FDR’s “Irreconcilable” Enemies

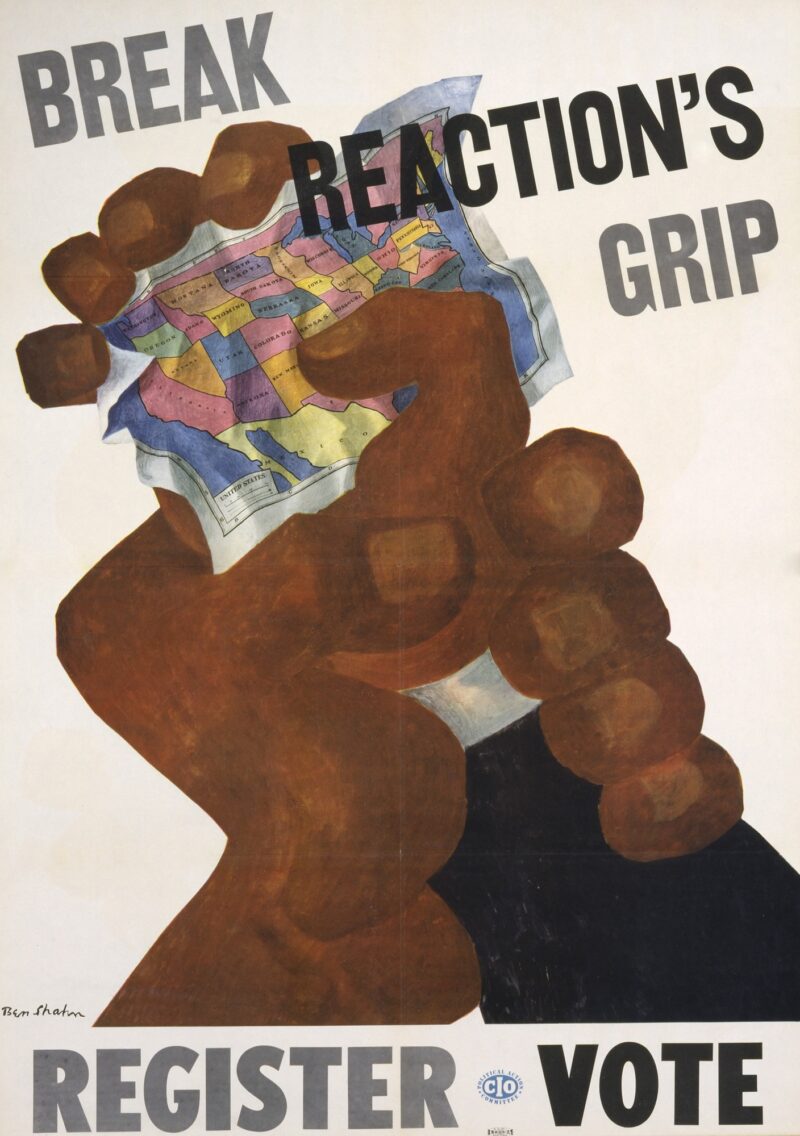

The New Deal—and subsequent modern liberal programs—deployed progressive taxation, social spending, and public investment to challenge private inheritance as the primary means of social reproduction and mobility in the United States. As the stalwart segregationists on the Senate Finance Committee knew, the New Deal held the potential to mobilize workers across the color line into a political force mighty enough to break the grip of white wealth—despite the deliberate omissions, concessions, inequities, and perpetrations of New Deal programs with respect to race, gender, and sexual orientation, and notwithstanding its deference to the private sector.4

Determined to derail Roosevelt’s agenda and to thwart the anti-racist and pro-labor segments of the Democratic Party, FDR’s “irreconcilable” southern foes on the Senate Finance Committee—Senator Pat Harrison (D-MI), Senator Josiah W. Bailey (D-NC), Senator Harry F. Byrd Sr. (D-VA), and Senator Walter F. George (D-GA)—organized the first bipartisan, cross-sectional alliance against the New Deal. All these men hailed from southern “pockets of authoritarian rule” characterized by a single political party, the system of racial segregation and terror known as Jim Crow, and the disenfranchisement of Black and poor white voters alike. Because the irreconcilables sat atop single parties that mixed patronage with voter suppression, they escaped primary challenges in their home states. Returning to the Senate term after term, they gained seniority, which entitled them to important committee positions. For roughly thirty years, the irreconcilables on the Senate Finance Committee ruled over federal tax policy, nearly uninterrupted.5

Why did FDR’s most implacable and potent foes choose the capital gains tax preference as the ground upon which they took their stand against the New Deal? Because reduced tax rates on income from investment—received overwhelmingly by the wealthiest households—blunted the progressivity of the federal income tax code. This buffered white wealth against the full costs of the economic benefits, entitlements, guarantees, and protections that the New Deal and subsequent modern liberal programs provided the working class (predominantly, but not only, white workers). And the capital gains tax preference cost the government nothing, which thrilled these vigilant budget hawks. The IRS simply collected less tax.6

The irreconcilables stood for plutocratic apartheid, and not with the New Deal. To be sure, all southern Democrats scrutinized every aspect of FDR’s programs for compatibility with their system of regional autonomy and racial segregation. Accordingly, the New Deal never challenged Jim Crow directly. Policies and programs—social insurance, labor rights and protections, job and relief programs, lending programs—benefited African Americans only in a limited way. They exempted industries in which Black people worked (particularly agriculture and domestic service); they accepted discriminatory local implementation and all-white labor unions.7

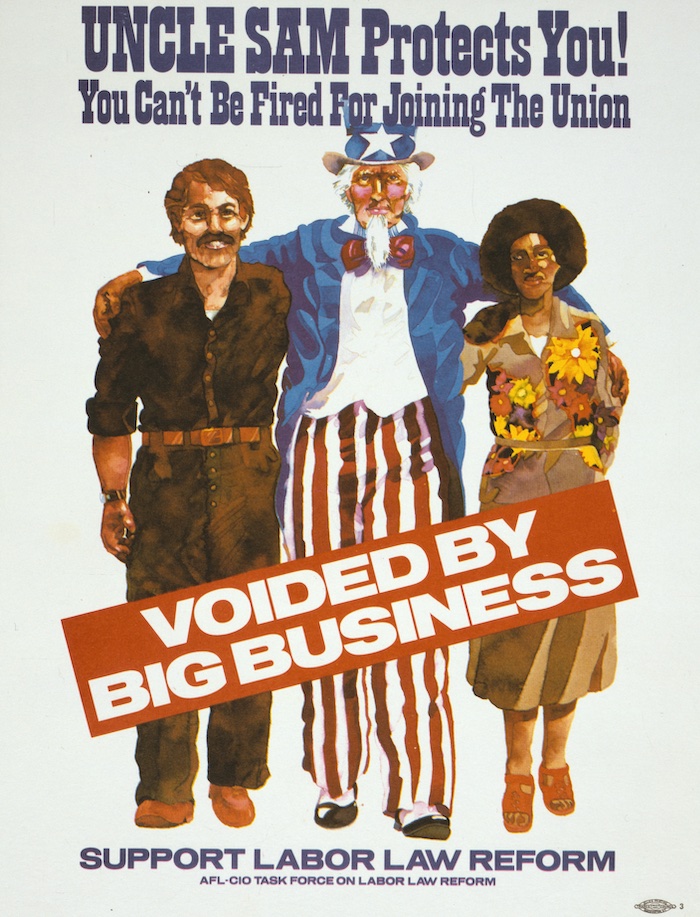

Even so, the irreconcilables spied serious threats to the power of white wealth, and to the privileged position of the southern caucus within the national Democratic Party. Even with the capital gains tax preference in place, the New Deal added to the tax burden of well-to-do whites and to the federal deficit. Worse, it built competing networks of patronage. If emboldened by federal largesse and labor rights, poor whites in the South might push back against the patronage networks that kept the irreconcilables in power—and perhaps even against segregation itself. The “long civil rights movement” was well underway. White workers poured into southern labor unions after the passage of the National Industrial Recovery Act (1933) and the National Labor Relations Act (1935) established workers’ right to organize and to join unions. The nationwide textile strike of 1934 proved that New Deal covenants with Jim Crow would not be enough to preserve the system of low-wage labor upon which southern manufacturers depended. And their political “donations” paid the poll taxes of the irreconcilables’ clients, which kept the irreconcilables in office.8

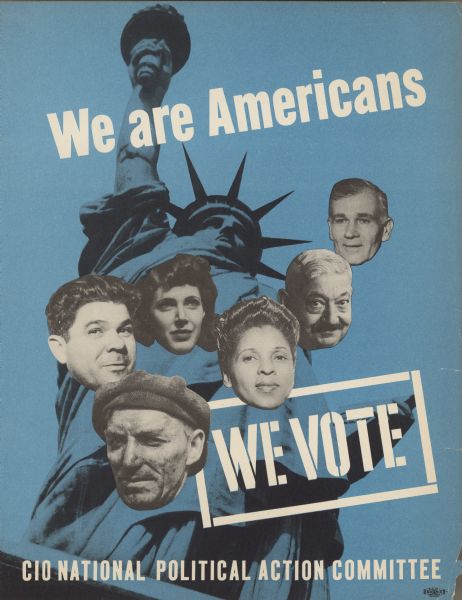

Developments within the national Democratic Party stoked the irreconcilables’ mounting unease. In 1936, the Party abolished its rule requiring a two-thirds vote to nominate a candidate for President, robbing the southern delegation of its veto over the nomination. Subsequently, the popular votes that delivered Roosevelt’s resounding reelection came from members of unions that belonged to the new, racially integrated Committee for Industrial Organization (after 1938, the Congress of Industrial Organizations, or cio), which supported civil rights for African Americans. As Black and white ethnic voters built up party ranks in the industrial North and Midwest, “rumors” circulated about a possible “organization of Negro Democrats” in the South. “It is well understood here that the President is going forward,” Senator Josiah Bailey (D-NC) wrote. “He is looking to get [cio leader] John Lewis to assist him . . . to get the negro vote.”9

In December 1937, Bailey and Senator Arthur Vandenberg Sr. (R-MI)—a sentinel for cio-beleaguered auto companies—released the “Conservative Manifesto.” First and foremost, it demanded a sharp reduction of capital gains taxes “to free funds for investment . . . in expanding business [and] larger employment.” Both “self-dependence” and “natural impulses of kinship and benevolence” toward the “deserving” unemployed would then be restored, the authors predicted. “Non-political administration” of “public relief” on a local, “non-partisan and temporary” basis could then resume. Charting a path for modern conservatism, Bailey and Vandenberg called for the “maintenance of States’ rights, home rule, and local self-government,” a balanced federal budget, “the maintenance of law and order” in labor relations, and the end of “government competition with private enterprise and investment” embodied in the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC).10

Roosevelt hit back. In the 1938 midterm campaigns, the Administration identified the South as the nation’s “number one economic problem,” blaming segregation for depressing the wages and purchasing power of Blacks and whites alike in the region. In Georgia, FDR stumped against the Chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, Senator Walter F. George (D-GA). But when the President likened the South to a “feudal” and “fascist system,” he enraged the irreconcilables, their patrons, and their clients.11

How dare Roosevelt presume “to interfere in the Southern states, to appraise and solve the problems of the Southern people,” fumed Senator Josiah Bailey. Much like during Reconstruction, the New Deal sent “armies of so-called uplifts” to “meddle” in southern “affairs, racial and social.” But manufacturers knew better, Bailey professed. The South offered refuge from rising wages and CIO militants. White workers in the South—“native born for from six to ten generations”—were not “afflicted with the European proletarian migration.”

We do not want the sort of population we hear of in New York, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Massachusetts, the melting-pot population [with] no affinity for true American republican institutions—[under] the influence . . . of agitators whose names end with “ski” and “stein”—to Dubinskis and Brophys. Our people have the Saxon capacity for order, they have no affinity for agitators, they are not sit-down strikers . . . [they cherish] English liberties, the common law and the Bible.

Perhaps “negroes” had seized “the balance of power in certain Northern states,” but in the South, “we will always have a white man’s party,” Bailey vowed. “We will not permit the Northern Democrats to frame a race policy or any social policy.”12

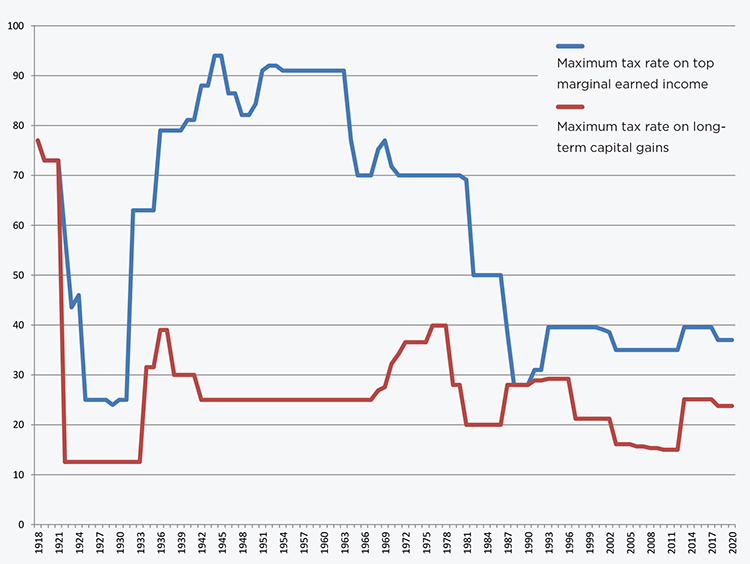

FDR’s attempt to purge the irreconcilables backfired. When the Senate reconvened, the irreconcilables trounced anti-lynching legislation. They passed the Revenue Acts of 1938 and 1939, which slashed tax rates on capital gains. To safeguard their moral economy of “whites-only” wealth, the irreconcilables hardwired the preferential treatment of capital gains into the fiscal machinery of the same modern liberal state that they so abhorred.

From their perch on the Senate Finance Committee, the irreconcilables kept vigil for three decades. They checked efforts to restructure the economy, to enlarge social benefits, or to extend even basic federal protections to African Americans. On their watch, the difference between the tax rates on top ordinary incomes and those on capital gains grew from 39 percentage points in 1937 to 45 points in 1965. Although historians tend to characterize this period as one of compressed inequality, the share of total wealth held by the top 1 percent and top 10 percent of US wealth-holders leveled out at about 28 percent and 70 percent, respectively, after 1940. In Europe, by contrast, wealth inequality continued to decline throughout the 1970s.13

The Defense of White Wealth in World War II

Economic mobilization for World War II battered the moral economy of elite, “whites-only” wealth. Wartime taxation cut into profits and investment returns. Full employment and unionization threatened employers’ authority. Federal policies targeted racial apartheid. The South shook as Black workers poured out of the region. The federal government prohibited racial discrimination in military conscription and defense industry work. Black voters and Black soldiers in the North moved racial integration to top of the liberal agenda. They pressed for bills to outlaw poll taxes, all-white primaries, and lynching. NAACP membership multiplied eightfold, while FDR called for federal legislation to guarantee the voting rights of all veterans—white and Black.14

Moreover, the astonishing rapidity and the massive scale of wartime public investment flatly contradicted claims about the potency of individual investors and the efficacy of private financial markets—claims upon which the preferential treatment of capital gains was based. In 1940, the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC)—the largest bank and the largest corporation in the United States at the time—established a new subsidiary, the Defense Plant Corporation (DPC). This federal agency soon became the most important source of investment in the nation and, indeed, in the entire world.15

To meet the colossal costs of World War II, lawmakers broadened the tax base (35.7 percent of the labor force paid personal income taxes in 1945, up from 5.8 percent in 1939). They raised tax rates on earned incomes and corporate incomes. But despite the administration’s wish to equalize tax rates on investment income with those levied on earned income, the irreconcilables managed to defend—and to expand—the preferential treatment of capital gains.16

The former leader of the RFC and the DPC, Emil Schram, emerged as the irreconcilables’ foremost fundraiser and tax-policy whisperer. In 1941, Schram left public service to accept a $50,000 salary offer from the New York Stock Exchange. Trading volume had collapsed. As a result, the revenue of NYSE member firms plummeted. Jesse Jones, Schram’s former boss at the RFC, predicted that only nationalization could save the Exchange. Schram disagreed. “The only way to get volume is to encourage people to trade,” he told the NYSE board of governors. Surmising that trading would pick up if Congress cut taxes on capital gains, the new president of the New York Stock Exchange set off for Washington, DC, to lobby for a “change in the tax law.”17

Schram had endeared himself to the irreconcilables back in 1938, when he refused Roosevelt’s request to fire the friends of Senator Walter F. George (D-GA) from their RFC positions. During George’s tenure as Chairman of the Senate Finance Committee (1941–1947, 1949, 1953), the Senator occupied a suite at the Mayflower in Washington, DC. So did the president of the Stock Exchange. Soon, the two men knew each other “very, very well.”18

Senator George tailored the Revenue Acts of 1942 and 1943 to NYSE specifications. These reductions on capital gains tax rates put the “Stock Exchange back in business,” Schram recalled with pride. He had proved Jesse Jones wrong.19

Tax cuts alone could not maintain NYSE trading volume. Nor could they secure the moral economy of “whites-only” wealth indefinitely. Schram knew he must challenge liberal and radical interpretations of the miraculous economic recovery achieved during the war. And the irreconcilables knew they must quash the postwar economic proposals offered by liberals, progressives, and radicals. Walter Reuther of the United Auto Workers proposed that DPC plants should be repurposed to build affordable housing and mass transit facilities; they could be leased to worker-owned cooperatives or to private corporations that agreed to equalize wage rates across regions (and, implicitly, between races). Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes advised that DPC assets be sold to veterans to provide “ten million young persons shares of stock in the America for which they risked their lives.” Others envisioned that state-owned DPC facilities, along with a robust federal National Resources Planning Board, could ensure full employment. Calls to make permanent the Fair Employment Practice Committee Postwar aimed to integrate the postwar prosperity that civil rights leaders anticipated. Up North, African American voters intensified their influence within the Democratic Party. So, too, labor unions. The dues of millions of members—including half a million Black workers—swelled the coffers of unions’ new political action committees.20

The NYSE president answered all these trends unequivocally: the “$10 billion of plant and property engaged in war production” owned by the federal government augured a “socialistic trend of dangerous significance.” Schram commanded that the federal government sell all DPC facilities to “leading industrial corporations” owned by “private investors.” The former leader of the DPC and the RFC coupled his dismissal of the agencies he once led with demands for cuts to capital gains tax rates. Together, Schram vowed, these “necessary incentives to . . . private enterprise” would liberate the “free flow of venture capital” and propel the postwar economy to levels of “maximum production and maximum employment.” Schram promised legislators, voters at campaign rallies, businessmen at association meetings, and citizens at war bond assemblies that capital gains tax reductions would increase federal revenue, because “the amount of tax revenue is in inverse proportion to the tax rate.” (Here, Schram anticipated so-called “supply-side” economics which, decades later, would be attributed to Arthur Laffer and his political acolytes such as Congressman Jack Kemp [R-NY]).21

In the South, Exchange emissaries learned the proper insinuations for flagging hazards to white supremacy. “You and I think alike,” the NYSE president winked at the Houston Chamber of Commerce when he stumped for Representative Hatton W. Sumners (D-TX), a resolute foe of anti-lynching legislation and the leader of congressional opposition to Roosevelt’s plan to “pack” the Supreme Court in 1936–1937. Echoing Bailey’s and Vandenberg’s “Conservative Manifesto,” Schram warned that taxes must never target “social purposes,” lest the nation “advance any farther in taking from the prudent and productive to maintain the improvident and indolent.”22

Ultimately, “financial help” from the NYSE kept “dependable” members of the Senate Finance Committee in office for another two decades. Schram “had no trouble raising the money to help in those campaigns” from NYSE members. The cash travelled back to Washington, DC, on Schram’s person, $50,000 per trip (nearly $1 million in 2022 dollars). “Of course it was [illegal],” he admitted later, “it’s always been illegal.”23

In 1955, another favorite of the NYSE—Senator Harry F. Byrd Sr. (D-VA)—assumed the chairmanship of the Senate Finance Committee (1955–1965). During World War II, Byrd had attracted the attention of fiscal conservatives across the country on account of his vocal criticism of labor unions, budget deficits, and racial integration. The “agencies” favoring “confiscatory” taxes on capital gains and inheritance would “next move” to “reform the South,” one New Yorker wrote to Byrd. “No one wants to invest money if . . . a gang of meddlers [will] destroy his investments” by taxing his gains to fund “‘socially minded’” programs, advised a Chicagoan.24

We middle-class conservatives, regardless of our party affiliation, and regardless of in what section of the country we live—North or South—have a common interest and it seems too bad that we can’t vote together in one party and keep things under control.

Stockbroker E. F. Hutton nearly had convinced the Virginian to run against Roosevelt on either the Independent or Republican ticket back in 1944. Instead, as Chairman of the Senate Finance Committee (1955–1965), Harry F. Byrd Sr. railed against Keynesian growth-liberalism, organized labor, federal deficits, and the welfare state. After Brown v. Board of Education (1954), Chairman Byrd ordered “massive resistance” against desegregation (in fact, he coined the term). In the decades to come, Chairman Harry F. Byrd Sr., his fellow champions of plutocracy and apartheid, and their successors on the Senate Finance Committee would view investors as a constituency that could be mobilized, across the Mason–Dixon Line, against modern liberalism and the threats it posed to racial and class hierarchies. Their paeans to investment on the part of individual Americans—and the pro-investor tax expenditures they legislated—would maintain, extend, and disguise their moral economy of “whites-only” wealth.25

Even as income inequality fell after World War II, even as white workers acquired homes in “red-lined” communities with federally guaranteed mortgages, and even as the gi Bill vastly enlarged the white middle class, wealth inequality held steady, thanks to the preferential tax treatment of capital gains. In other words, even white working and middle-class households gained little ground in terms of wealth relative to the richest households (almost exclusively white). Even a century after the end of the Civil War, Black Americans still held almost no wealth. As late as 1965, Black households held only 1.9 percent of the assets owned by all US households and only 0.9 percent of corporate stock.26

The Reconstruction of Structural Racism after 1965

After the passage of the Voting Rights Act (1965), the ability of incumbent southern Democrats to survive a multiracial electorate—and to arrest the party’s leftward turn—required a strategic mix of reinvention and concealment. Senator Russell B. Long (D-LA), the son of Governor (and Senator) Huey “Kingfish” Long (D-LA), managed to maintain his ascent within the Democratic Party and his commitment to preserving the rule of white wealth. In the Great Depression, the father had sloganeered “Share Our Wealth.” As Chairman of the Senate Finance Committee (1966–1987), the son introduced new tax expenditures that aimed to encourage and reward asset ownership by individual (white) households. Or, as Chairman Long explained it, he aimed to make “haves out of the have-nots without taking it away from the haves” through the federal income tax code.27

In truth, these new pro-investment tax expenditures encouraged and rewarded investment by upper-middle-class white households, subsidizing their acquisition and accumulation of assets, particularly financial assets. These households possessed sufficient disposable income to make investment possible; they held the kind of lucrative and secure jobs that might offer tax-free or tax-deferred benefits. “I’ve never been confused about it,” Long mused in 1977. “I’ve always known what we were doing was giving government money away.” Under Chairman Long, the “hidden welfare state” for affluent white households grew to equal nearly half the size of the visible welfare state of cash transfers.28

Chairman Long understood the white supremacist origins, intent, and consequences of pro-investment tax expenditures perfectly well. He had cut his teeth on the Senate Finance Committee under the tutelage of his father’s great foe, Chairman Harry F. Byrd Sr. Rising through the ranks during the Johnson Administration, Senator Long had supported War on Poverty programs; he even voted for the Economic Opportunity Act (1964). Still, he remained firmly committed to the “racial caste system” that trapped African Americans in low-wage, unskilled, and insecure jobs. Long strenuously opposed “expanded income support for the ‘able-bodied’ poor,” especially for unmarried women of color, whom he denigrated viciously. Chairman Long and his ilk recoiled from the “tax-and-spend” liberalism that directed tax dollars towards so-called undeserving minorities via growing programs like Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC). From the mid-1960s, demands to expand AFDC were led by the National Welfare Rights Organization, an activist group that Long disparaged as “Black Brood Mares, Inc.” after the organization occupied his hearing room in 1967. In response, Chairman Long devised the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) for the working poor. Enacted in 1975, when Black unemployment stood at 2.5 times the level of white unemployment, EITC torpedoed Nixon’s Family Assistance Plan, a guarantee of minimum income to all families.29

The second major architect of the hidden welfare state for affluent white families was Senator Lloyd Bentsen (D-TX). In 1971, Bentsen entered the Senate after a dirty primary victory against progressive icon Senator Ralph Yarborough. Yarborough’s defeat to Bentsen signaled the end of the road for the “Democratic Coalition,” an egalitarian, grassroots, multiracial alliance of the labor-Left that pounded Jim Crow and Juan Crow with its insistence on “labor rights, economic justice, and real political power” for communities of color in the Lone Star state. Senator Bentsen could not afford to ignore labor’s grassroots or constituents of color. So while he staked his positions to the right of Yarborough, Bentsen planted them in different territory.30

Senator Bentsen embraced the booming Texas oil services industry, along with its ancillaries in finance, insurance, and real estate (FIRE). There, employees were unorganized, well-educated, white, and male. These industries stood poised to take off as concerns mounted over the nation’s dependence on foreign oil and as the hidden welfare state swelled. Appointed to the Senate Finance Committee in 1974, Bentsen charted a self-styled “centrist” course for the Democratic Party. In truth, it traced the same fiscal trajectory set by Chairman Long and his apartheidist predecessors. In time, Bentsen succeeded Long as committee chairman (1987–1993). Later, he became Secretary of the Treasury (1993–1994) in the Clinton Administration—which reduced capital gains taxes and abolished AFDC.

Bentsen’s first foray into the hidden welfare state for asset-holding white households—and his initiation by FIRE lobbyists and executives—took place during the formulation of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (1974). ERISA regulates and guarantees the funds that finance the benefits US employers offer their workers. For workers not covered by an employer-sponsored plan, the law established the individual retirement account (IRA), which allows a taxpayer’s investment contributions and gains to escape taxation until they are withdrawn in retirement.

As Bentsen steered ERISA through Congress, the lobbyists, consultants, and executives of the companies that serviced and acted as the custodians of large benefit plans—banks, insurance companies, brokerages, and mutual funds—schooled the senator from Texas and his colleagues in their pro-investor, finance-centered theories of political economy. (Journalists and pundits slapped the label “supply-side economics” on this rather old set of assumptions.) The decade’s economic malaise stemmed from an underlying crisis of capital formation, they advised the junior Senator. The first and most essential step in the process of capital formation was the “pooling” of liquid financial assets that entrepreneurs and employers could tap in order to launch and expand their enterprises. Only those measures that increase the aggregate amount of these liquid financial assets could raise aggregate employment without fueling inflation, FIRE spokesmen and leaders advised.31

The conceptualization of capital formation codified in ERISA broke with the growth-oriented Keynesianism of modern liberalism and with demands pressed by the Left in the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s for expansive redistributive programs. Government would not “pick winners” through industrial policy tailored to create jobs, nor conduct bailouts to protect jobs, nor act as employer of last resort via public-sector employment (as proposed in the 1966 “Freedom Budget” presented by civil rights leaders Bayard Rustin and A. Phillip Randolph). Led by Bentsen, policymakers imagined that under ERISA, the potent forces of capital formation would raise employment without invoking inflation. Moving toward FIRE and away from organized labor, ERISA presaged the quixotic centrism of the so-called New Democrats of the 1980s and 1990s, who championed “private sector investment,” entrepreneurship, and “market-based tools” as the best solutions for poverty, inequality, and racism—and eschewed completely “redistribution, government assistance,” and the goal of economic security.32

In its final form, ERISA aimed to safeguard and to augment workers’ health care and retirement—and to stimulate capital formation—by regulating and guaranteeing the funds that under-wrote the tax-free plans that employers offered to workers in the United States. ERISA, however, disallowed labor unions from selecting investments (a practice that Senator Byrd Sr. excoriated in 1946 as “the complete destruction of the private enterprise system in the United States”). After ERISA, professionally managed pension funds disinvested from the nation’s industrial manufacturing core, just as the unionized jobs in that sector began to desegregate. Within a decade, the financial sector overtook manufacturing in its share of US GDP. But FIRE added no net jobs.33

As successors to the irreconcilables, Long and Byrd Jr. safeguarded the moral economy of “whites-only” wealth by expanding the ranks of its beneficiaries to include growing numbers of professionals and managers, thanks to the tax expenditures codified in ERISA.

But in 1974, when ERISA passed, organized labor stood at a high point. Union membership reached 24 percent. In the 1970s, unions pressed into sectors and industries passed over by the so-called Treaty of Detroit. Women and people of color took center stage in the labor movement, after previously being shut out of high-wage, union jobs that might offer tax-exempt, employer-sponsored benefits. Emboldened by the Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1968, and by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (1964), minorities and women turned to grassroots actions and legal challenges to demand access, rights, and leadership in the workplace and within unions. They carried the fight against gender and racial discrimination to housing and credit markets, punitive and demeaning welfare policies, and the institutional abuse exposed by uprisings in the nation’s urban centers and prisons. As a result of all these efforts, racial disparities in the rate of employment, the rate of homeownership, median income, and even median wealth narrowed somewhat from the mid-1960s until about 1980.34

Potent grassroots movements on the Left pressed even further, assailing the so-called liberal consensus that governed postwar America. They took aim at its fiscal structure—especially tax expenditures that benefit the wealthy and corporations. Here, they found common ground with middle-class tax revolts. Tax avoidance bothered legislators on both sides of the aisle, with conservatives looking for revenue to close the budget deficits that they believed caused inflation. In 1972, presidential candidate George McGovern (D-SD) vowed to abolish the capital gains tax preference in an effort to distribute the nation’s tax burden more equitably. In 1976, candidate Jimmy Carter (D-GA) signaled that his administration would “treat all income the same,” equalizing the tax rates on capital gains with those levied on ordinary wage and salary income.35

But when President Carter called for legislation, junior congressmen balked. Voter dissatisfaction had swept a large cohort of rookies from both parties into office after Watergate. Neither diverse nor radical, the “Class of ʼ74”—also known as the “Watergate babies”—nonetheless fancied themselves as anti-establishment mavericks. They hankered for new policy ideas to address unemployment, inflation, deindustrialization, and the declining position of the United States in international trade. Up-and-comers, including Senators Lloyd Bentsen (D-TX), Bob Dole (RKS), William Roth (R-DE), Bill Bradley (D-NJ), and Representative William Steiger (R-NY), harkened to the counsel of new political lobbies established by the venture capital, electronics, and asset management industries. Ultimately, these Congressmen—who dominated federal tax policy for remainder of the century—enhanced existing tax expenditures. They added new ones congruent with their emerging finance-centered, bipartisan vision for a post-industrial, post-union, post-racial economy in which every household held financial assets.36

This cohort in Congress owed nothing to “old” labor institutions and bosses, the grassroots Labor-Left, or to the Civil Rights, Black Power, or women’s rights movements. Savvy senior incumbents like Chairman Long and Senator Byrd Jr. (I-VA) knew how to play with the Watergate babies. Speak their language. “The challenge,” explained Senator Byrd Jr. (who assumed his father’s Senate seat in 1965), “is to construct economic and tax policies which provide more jobs for Americans without inflation . . . That’s why we’re taking up capital gains reductions . . . Our productive capacity must expand and modernize if we are to be competitive internationally.” Let them do the legwork. Let them bask in the media spotlight. And make no mention of history.37

And so, congressional newbies took center stage in federal tax policy, beginning with the so-called Steiger Amendment to the Revenue Act of 1978. Both President Carter and Senator Edward Kennedy proposed to stimulate capital formation through changes to the corporate tax code (specifically, acceleration of depreciation schedules for corporate assets). But, thanks to the Steiger Amendment, the Revenue Act of 1978 instead slashed capital gains taxes on households. In accordance with FIRE lobbyists’ ambitions to promote investment by individuals, the Revenue Act of 1978 also introduced tax-deferred defined contribution 401(k) retirement plans.

Representative William A. Steiger (R-WI), a moderate Republican, knew nothing about high tech or venture capital. Precisely, for this reason, the newly formed American Council for Capital Formation—helmed by the legendary corporate lobbyist Charls Walker—handpicked the thirty-eight-year-old from Oshkosh, Wisconsin, to make its case in Congress. “High tech industries and venture investors” identified capital gains tax rates as “the root cause of inadequate capital” formation, Steiger related to his colleagues on the Ways and Means Committee. Adequate capital formation originated in increased investment by households.38

I feel strongly about this issue,” Senator Lloyd Bentsen concurred.

For 200 years, this country has prospered because we have had a free enterprise system that has encouraged the entrepreneur, the small businessman, to take a risk with the understanding that he was going to be able to keep some of it, if he won. We have not succeeded as a nation by playing it safe . . . but the rewards are even less with our tax system. . . . If you do not leave something for the risk-takers, there is not going to be anything for the caretakers to care for in this country of ours.

Bentsen’s Republican counterpart, Senator William V. Roth (R-DE), agreed. “Not every society has been endowed and has prospered by the investment decisions of its private citizens . . . In an open society, these decisions are more properly left to private individuals.” If tax rates on capital gains were reduced, Roth explained, investors would retain a larger portion of their investment returns after they paid their taxes. This would encourage individuals to invest more, and by doing so, individuals would regain their influence over the allocation of investment across the economy.39

Deliberations over the Revenue Act of 1978 were infused with concerns about the rapid rise of pension funds and other institutional investors after the passage of ERISA. What would be the fate of the individual investor and the entrepreneur if big pensions invested big labor’s money in big business? In the wake of ERISA, tax-free retirement contributions by employers and employees flooded into pension funds. By 1978, these institutional investors dominated the market for the stocks and bonds of US corporations. Although ERISA prohibited unions from wielding pension funds as arsenals of class conflict, these funds raised the specter of “pension fund socialism,” nonetheless.40

The Revenue Act of 1978 slashed capital gains taxes for individuals to pre–New Deal levels; it allowed employers to offer tax-free defined contribution retirement plans. In these plans, employees choose how to invest their untaxed contributions and how to reinvest their untaxed gains in their individual 401(k) account. Within two decades, the majority of US households owned corporate stock—mostly through tax-advantaged mutual funds held in individual 401(k) accounts. The distribution of this retirement wealth, however, always would skew heavily toward affluent white households.

The legislation also marked a breakthrough victory for Republican “supply-siders” and for the market-oriented Democrats who anticipated the New Democrats of the Clinton era. Both groups now concurred that “any capital formation technique” would necessarily benefit “high-bracket taxpayers” more, in the words of Representative Al Ullman (D-OR), Chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee. According to the emerging neoliberal consensus, inequality was the price that society must pay for economic growth and progress. The racial dimensions of inequality would be ignored.41

Ultimately, the vast expansion of pro-investment tax expenditures in the 1970s blunted and then reversed the economic gains that African Americans made relative to whites after Brown, the Voting Rights Act, and the Civil Rights Acts. While Black people obtained legal relief from discrimination in labor, housing, and credit markets, the courts never scrutinized tax expenditures. Racial disparities in income and wealth widened once more. By 2020, the ratio of white wealth (per capita) to black wealth (per capita) stood at approximately 6:1—roughly the same ratio that existed when the Civil Rights Act passed Congress in 1964. What changed? The top 1 percent of wealth-holders increased their share of wealth from 28 percent to over 38 percent as the effective federal tax rate paid by the top 1 percent of incomes fell from 41 percent to 30 percent.42

Tax Expenditures Are Structural Racism

For centuries, individuals and families deemed “white” have amassed assets and accumulated wealth across generations, thanks to privileges and protections granted by society and by the state. In contrast, Black Americans’ efforts to build wealth have been thwarted by discrimination, exploitation, expropriation, and violence—harms perpetrated by individuals and by institutions, both public and private, across centuries. In the twentieth century, a moral economy of “whites-only” wealth animated federal policies and programs that created the propertied white middle class. By design, those asset-building programs excluded Black households, particularly with discriminatory lending and realty practices in the housing market. The end of de jure segregation and waning of overt discrimination in education, employment, housing, and credit access did not reduce racial gaps in household wealth. Pro-investment tax expenditures sustained and quickened the accumulation of wealth by affluent white households, while tax-free gifts and bequests safeguard the conveyance of wealth to the next generation of affluent white Americans.43

The United States’ massive system of tax expenditures is, perhaps, the most enduring legacy of some of the most virulent white supremacists to sit in the United States Congress in the twentieth century. This hidden welfare state sustains the irreconcilables’ moral economy of “whites-only” wealth down to our present day. The United States spends more on private social benefits—subsidized by tax expenditures—than any other nation, both per capita and in total. In 2022, the federal government surrendered the equivalent to 8.3 percent of GDP to tax expenditures. Pro-investor tax expenditures totaled an estimated $657 billion. This is enough to fund ample investments in sustainable, care-centered infrastructure, social benefits, and other policies to reduce any of the myriad forms of inequality in the United States—all of which continue to be marked by profound racial inequity.44

This essay was published in the Moral/Economies issue (Winter 2022).

Julia Ott is associate professor of history at the New School, where she co-founded the Robert L. Heilbroner Center for Capitalism Studies. Her research and writing examines the historical relationships between finance, politics, and culture in the United States. Currently, Ott is writing two books: Why Is Wealth White? and What Was Venture Capital? Her first book, When Wall Street Met Main Street (Harvard University Press, 2011), won the Vincent J. DeSantis prize. Other awards include fellowships from the Russell Sage Foundation, Institute for Advanced Study (Princeton, NJ), and New America.Header image: Andy Warhol, Flickr, Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0).NOTES

- Highest quintile of earners is calculated before taxes and transfers. Congressional Budget Office (CBO), “The Distribution of Major Tax Expenditures in 2019” (CBO, Washington, DC, October 2021), www.cbo.gov/publications/57413#datak; US Department of the Treasury, “Tax Expenditures FY2024” (US Department of the Treasury, Washington, DC, October 2022), https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/tax-policy/tax-expenditures.

- Robert S. Browne, “Wealth Distribution and Its Impact on Minorities,” The Review of Black Political Economy 4, no. 4 (December 1974): 27–38; Maury Gittelman and Edward N. Wolff, “Racial Differences in Patterns of Wealth Accumulation,” Journal of Human Resources 39, no. 1 (Winter 2004): 193–227; Edward N. Wolff, “Household Wealth Trends in the United States, 1962–2016: Has Middle Class Wealth Recovered?” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 24085 (November 2017), http://www.nber.org/papers/w24085; Edward N. Wolff, “Deconstructing Household Wealth Trends, 1983–2013” (working paper no. 22704, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, September 2016), https://www.nber.org/papers/w22704; Dionissi Aliprantis, Daniel R. Carroll, and Eric R. Young, “The Dynamics of the Racial Wealth Gap” (working paper 19-18, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, Cleveland, OH, October 8, 2019), https://doi.org/10.26509/frbc-wp-201918; and Moritz Kuhn, Moritz Schularick, Ulrike I. Steins, “Wealth Inequality in America, 1949–2016” (Institute Working Paper 9, Opportunity and Inclusive Growth Institute, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, Minneapolis, MN, June 14, 2018), https://www.minneapolisfed.org/research/institute-working-papers/income-and-wealth-inequality-in-america-1949-2016. Urban Institute, “Racial Disparities and the Income Tax System” (January 30, 2020), https://apps.urban.org/features/race-and-taxes/; Julia Ott, “Tax Preference as Racial Privilege in the United States, 1921–1965,” Capitalism: A Journal of History and Economics 1, no. 1 (Fall 2019): 92–165; Tom Neubig, “Disparate Racial Impact: Tax Expenditure Reform Needed,” Tax Notes Federal 170 (March 8, 2021); Neil Bhutta, Andrew C. Chang, Lisa J. Dettling, and Joanne W. Hsu, “Disparities in Wealth by Race and Ethnicity in the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances,” FEDS Notes (September 28, 2020); Tax Policy Center, “Tax Benefit of the Preferential Rates on Long-Term Capital Gains and Qualified Dividends, Baseline: Current Law, Distribution of Federal Tax Change by Expanded Cash Income Percent, 2019” (Table T20-137, Tax Policy Center, 2020), https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/model-estimates/individual-income-tax-expenditures-april-2020/t20-0137-tax-benefit-preferential; Chye-Ching Huang and Roderick Taylor, “How the Federal Tax Code Can Better Advance Racial Equity” (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Washington, DC, July 25, 2019), https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/7-25-19tax.pdf.

- The term “hidden welfare state” is taken from Christopher Howard, The Hidden Welfare State: Tax Expenditure and Social Policy in the United States (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999). See also Suzanne Mettler, The Submerged State: How Invisible Government Policies Undermine American Democracy (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2011); Christopher G. Faricy, Welfare for the Wealthy: Parties, Social Spending, and Inequality in the United States (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2016); William Darity Jr., Darrick Hamilton, Mark Paul, Alan Aja, Anne Price, Antonio Moore, and Caterina Chiopris, “What We Get Wrong About the Racial Wealth Gap” (DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity, Insight Center for Community Economic Development, April 2018), https://socialequity.duke.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/what-we-get-wrong.pdf. For the disproportionate benefits received by white families, see Dorothy Brown, The Whiteness of Wealth: How the Tax System Impoverishes Black Americans—and How We Can Fix It (New York: Crown, 2021); Beverly I. Moran and William Whitford, “A Black Critique of the Internal Revenue Code,” Wisconsin Law Review 751 (1996).

- N. D. B. Connolly, “Strange Career of American Liberalism,” in Shaped by the State: Toward a New Political History of the Twentieth Century, ed. Brent Cebul, Lily Geismer, and Mason B. Williams (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019), 62–95; N. D. B. Connolly, A World More Concrete: Real Estate and the Remaking of the Jim Crow South (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014); Ira Katznelson, When Affirmative Action Was White: An Untold History of Racial Inequality in Twentieth-Century America (New York: Norton, 2006); Suzanne Mettler, Dividing Citizens: Gender and Federalism in New Deal Public Policy (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1998); Margot Canaday, Building the Straight State: Sexuality and Citizenship in Twentieth-Century America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009); Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (New York: Liveright, 2017). For the New Deal working through private institutions, see Christy Ford Chapin, Ensuring America’s Health: The Public Creation of the Corporate Health Care System (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2015); Jennifer Klein, For All These Rights: Business, Labor, and the Shaping of America’s Public-Private Welfare State (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003); Martjin Konings, The Development of American Finance (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2011); Louis Hyman, Debtor Nation: History of America in Red Ink (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011); Elisabeth Tandy Shermer, Indentured Students: How Government Guaranteed Loans Left Generations Drowning in Debt (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2021); Louis Hyman, Temp!: The Real Story of What Happened to Your Salary, Benefits, and Job Security (New York: Penguin, 2019); Brent Cebul, Illusions of Progress: Business, Poverty, and Liberalism in the American Century (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, forthcoming).

- The designation “irreconcilable” comes from James T. Patterson, Congressional Conservatism and the New Deal: The Growth of the Conservative Coalition in Congress (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1967). See also Robert Mickey, Paths Out of Dixie: The Democratization of Authoritarian Enclaves in America’s Deep South, 1944–1972 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015); Brent Tarter, The Grandees of Government: The Origins and Persistence of Undemocratic Politics in Virginia (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2013); Sean Farhang and Ira Katznelson, “The Southern Imposition: Congress and Labor in the New Deal,” Studies in American Political Development 19 (Spring 2005); Ira Katznelson, Kim Geiger, and Daniel Kryder, “Limiting Liberalism: The Southern Veto in Congress, 1933–1940,” Political Science Quarterly 108 (Summer 1993): 283–302; Ira Katznelson, Fear Itself: The New Deal and the Origins of Our Time (New York: Norton, 2013); Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore, Defying Dixie: The Radical Roots of Civil Rights, 1919–1950 (New York: Norton, 2008); Nancy Maclean, Democracy in Chains: The Deep History of the Radical Right’s Stealth Plan for America (London: Scribe Publications, 2017); Nancy Maclean, “Neo-Confederacy versus the New Deal: The Regional Utopia of the Modern American Right,” in The Myth of Southern Exceptionalism, ed. Mathew D. Lassiter and Joseph Crespino (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 308–323; Katherine Rye Jewell, Dollars for Dixie: Business and the Transformation of Conservatism in the Twentieth Century(Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2017).

- In his first term, President Franklin D. Roosevelt proposed tax policies intended to dilute the concentration of income and wealth in the United States. Exposés had revealed that the richest Americans avoided paying income tax during the Great Depression, while Senator Huey Long (D-LA) intensified public demand for economic redistribution with his campaign to “Share Our Wealth.” The Revenue Act of 1934 raised tax rates on capital gains from 12.5 percent to 31.5 percent, while the Revenue Act of 1935 hiked rates on uppermost earned incomes and on inheritances and estates. W. Elliot Brownlee, Federal Taxation in America: A History (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 119–131, 131; Monica Prasad, Land of Too Much: American Abundance and the Paradox of Poverty (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012), 125–141; Ronald Frederick King, “From Redistributive to Hegemonic Logic: The Transformation of American Tax Politics, 1894–1963,” Politics and Society 12, no. 3 (September 1983): 32–33; Mark H. Leff, The Limits of Symbolic Reform: The New Deal and Taxation, 1933–1939 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1984), 48–202; Romain D. Huret, American Tax Resisters (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014), 141–172; Joseph J. Thorndike, Their Fair Share: Taxing the Rich in the Age of FDR (Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute Press, 2013), 105–168; Joseph J. Thorndike, “‘The Unfair Advantage of the Few’: The New Deal Origins of ‘Soak the Rich’ Taxation,” in The New Fiscal Sociology: Taxation in Comparative and Historical Perspective, ed. Isaac William Martin, Ajay K. Mehrotra, and Monica Prasad (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 29–47.

- Ira Katznelson, When Affirmative Action Was White: An Untold History of Racial Inequality in Twentieth-Century America (New York: Norton, 2006), 20–55; Robert Lieberman, Shifting the Color Line: Race and the American Welfare State (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998); Joseph E. Lowndes, Julie Novkov, and Dorian T. Warren, Race and American Political Development (London: Routledge, 2012); Linda Faye Williams, Constraint of Race: Legacies of White Skin Privilege in America (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2003).

- Katznelson, Fear Itself, 6–25, 86–96, 127–128, 144–178, 230–273, 471–479; Ajay Mehotra, “Fiscal Forearms: Taxation as the Lifeblood of the Modern Liberal State,” in The Many Hands of the State: Theorizing the Complexities of Political Authority and Social Control, ed. Kimberly Morgan and Ann Orloff (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2017); Tarter, Grandees of Government; Douglas Carl Abrams, Conservative Constraints: North Carolina and the New Deal (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1992); Anthony J. Badger, Prosperity Road: The New Deal, Tobacco, and North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1980); Jacquelyn Dowd Hall, “The Long Civil Rights Movement and the Political Uses of the Past,” Journal of American History 91, no. 4 (March 2005): 1233–1263; Jane Dailey, Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore, and Bryant Simon, Jumpin’ Jim Crow: Southern Politics from Civil War to Civil Rights (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000); Gilmore, Defying Dixie, 4, 29–56, 65–99, 108–134; Robert Korstad, Civil Rights Unionism: Tobacco Workers and the Struggle for Democracy in the Mid-Twentieth-Century South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003); Patricia Sullivan, Days of Hope: Race and Democracy in the New Deal Era (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996); John Egerton, Speak Now Against the Day: The Generation Before the Civil Rights Movement in the South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995); George A. Sloan to B. B. Gossette, May 16, 1935, folder “Taxes and Tariff—1936, May,” box 251, Josiah W. Bailey Papers, University of North Carolina; Janet Irons, Testing the New Deal: The General Textile Strike of 1934 in the American South (Urbana-Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2000); Gilmore, Defying Dixie, 178–179; Tarter, Grandees of Government; Jewell, Dollars for Dixie.

- Eric Schickler, Racial Realignment: The Transformation of American Liberalism, 1932–1965 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016), 3–13, 21–23, 52–79, 246; Josiah W. Bailey to Julian Miller, May 18, 1937, folder “Political: National—1937, January to July,” box 475, Josiah W. Bailey Papers, University of North Carolina.

- Josiah W. Bailey, “An Address to the People of the United States: A Declaration of Principles” (Stamford CT: Overbrook Press, December 1937), folder “Political: National—1937, December to 1938, February,” box 475, Josiah W. Bailey Papers, University of North Carolina.

- Gilmore, Defying Dixie, 231–234; Patterson, Congressional Conservatism, 262–285; Josiah W. Bailey, “The North as a National Problem: Address at the Young Democrats Convention, Durham, NC,” September 7, 1938, folder “Writings and Addresses, 1937–1938,” box 20, Josiah W. Bailey Papers, University of North Carolina; Franklin D. Roosevelt, “The United States Is Rising and Rebuilding on Sounder Lines: Address at Gainesville, Georgia, March 23, 1938,” https://quod.lib.umich.edu/p/ppotpus/4926315.1938.001/208.

- Josiah W. Bailey, “President Roosevelt Draws the Line,” February 1938, folder “Writings and Addresses, 1937–1938,” box 20, Josiah W. Bailey Papers, University of North Carolina; Bailey, “North as a National Problem”; Bailey to T. C. Coppedge, October 12, 1938, folder “Political: National–1938, October–November,” box 476, Josiah W. Bailey Papers, University of North Carolina.

- Julian E. Zelizer, “Confronting the Roadblock: Congress, Civil Rights, and World War II,” in Fog of War: The Second World War and the Civil Rights Movement, ed. Kevin M. Kruse and Stephen Tuck (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012); Brownlee, Federal Taxation in America, 136–139; David M. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War 1929–1945 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 345–350; Schickler, Racial Realignment, 71–72; see figure 10.4 in Thomas Piketty, Capital and Ideology (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2020), 423, http://piketty.pse.ens.fr/fr/ideology.

- Katznelson, Fear Itself, 337–345; James T. Sparrow, Warfare State: World War II Americans and the Age of Big Government (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 6, 11–12; Brinkley, End of Reform, 98, 141; Gilmore, Defying Dixie, 7, 335–401; Katznelson, When Affirmative Action Was White, 61–79; Patricia Sullivan, “Movement Building During the World War II Era: The NAACP’s Legal Insurgency in the South,” in Fog of War; Jason Morgan Ward, “‘A War for States’ Rights’: The White Supremacist Vision of Double Victory,” in Fog of War.

- Mark Wilson, Destructive Creation: American Business and the Winning of World War II (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016), 3–4; 190–239; Steven Fenberg, Unprecedented Power: Jesse Jones, Capitalism, and the Common Good (College Station: Texas A&M Press, 2011); Franklin D. Roosevelt, “State of the Union Message to Congress, January 11, 1944,” http://www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/archives/address_text.html.

- Sparrow, Warfare State; Brownlee, Federal Taxation in America; Steven A. Bank, Kirk J. Stark, and Joseph J. Thorndike, War and Taxes(Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute Press, 2008); Godfrey N. Nelson, “Eccles’ Proposal for Tax Discussed,” New York Times, March 25, 1945; Emil Schram, “Address before the Advertising Club of Baltimore, July 11, 1945,” in “Untitled Speeches 1945” folder, box 6, Record Group 2-2, NYSE Archives.

- “Interview with Emil Schram,” 42, interview by Jessica Holland, June 8, 1984, transcript, vol. 1, folder 5, box 1, Emil Schram Collection, Indiana Historical Society. Quoted with permission of the New York Stock Exchange.

- Interview with Emil Schram,” 52–55, interview by Jessica Holland, June 8, 1984, transcript, vol. 1, folder 5, box 1, Emil Schram Collection, Indiana Historical Society. Quoted with permission of the New York Stock Exchange.

- “Interview with Emil Schram,” 52–55, interview by Jessica Holland, June 8, 1984, transcript, vol. 1, folder 5, box 1, Emil Schram Collection, Indiana Historical Society. Quoted with permission of the New York Stock Exchange.

- Wilson, Destructive Creation, 5, 93–115; Sparrow, Warfare State, 248; Ickes quoted in Brinkley, End of Reform, 240–242.

- Emil Schram, “Informal off-the-record remarks by Emil Schram, President of the New York Stock Exchange at Connecticut Newcomer dinner, June 9, 1943,” in folder “Untitled Speeches 1943,” box 6, Record Group 2-2, NYSE archives; Emil Schram, “The Stock Exchange Today: An address delivered at a luncheon at Atlanta Rotary Club, May 10, 1943” in folder “Untitled Speeches 1943,” box 6, Record Group 2-2, NYSE Archives; Emil Schram, “Speech Delivered at the Annual Dinner of Houston Chamber of Commerce, December 18, 1946” in folder “Untitled Speeches 1946,” box 6, Record Group 2-2, NYSE Archives.

- Emil Schram, “Remarks at the Annual dinner of the Houston Chamber of Commerce, December 18, 1946,” in “Untitled Speeches 1946” folder, box 6, Record Group 2-2, NYSE Archives; Emil Schram, “Informal off-the-record remarks by Emil Schram, President of the New York Stock Exchange at Connecticut Newcomen dinner, June 9, 1943,” in “Untitled Speeches 1943” folder, box 6, Record Group 2-2, NYSE Archives.

- “Interview with Emil Schram,” June 8, 1984, 58, 95–65, Emil Schram Collection, Indiana Historical Society. Quoted with permission of the New York Stock Exchange Archives.

- Thomas Horace Evans to Josiah W. Bailey, January 18, 1938, folder “Taxes and Tariff: 1938, January,” box 253, Josiah W. Bailey Papers, University of North Carolina; G. Keith Funston to Honorable Harry F. Byrd Sr., November 12, 1965, folder 2-7, box 3, G. Keith Funston Correspondence, Record Group 2-2, NYSE Archives; G. Keith Funston to Honorable Harry F. Byrd Sr., March 16, 1964, folder 2-1, box 3, Group 2-2, G. Keith Funston Correspondence, Record Group 2-2, NYSE Archives; Philip S. to Josiah W. Bailey, Chicago, November 18, 1937, folder “Tax and Tariff—September to November, 1937,” box 353, Josiah W. Bailey Papers, University of North Carolina.

- Hermann L. Brandt to Harry F. Byrd Sr., February 8, 1943, folder “1943—7,” box 170, Harry Flood Byrd, Sr. Papers, University of Virginia; “Byrd For President” folders, box 169; Harry F. Byrd Sr., “We Are Losing Our Freedom,” American Magazine (1943); Harry F. Byrd Sr., “USA vs. The Frankenstein Monster,” Readers’ Digest (1943); E. F. Hutton to John Shepherd Jr., August 5, 1943, folder “1943–5,” box 170; E. F. Hutton to John Shepherd Jr., August 13, 1943, folder “1943–5,” box 170; John Shepard Jr. to Admiral Richard Byrd, March 31, 1943, folder “1943–8,” box 170; E. F. Hutton to Frank Gannett, April 23, 1943; Frank Gannett to E. F. Hutton, April 23, 1943, all in Harry Flood Byrd, Sr. Papers, University of Virginia; Kari Fredrickson, The Dixiecrat Revolt and the End of the Solid South, 1932–1968 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001); Keith M. Finley, Delaying the Dream: Southern Senators and the Fight Against Civil Rights, 1938–1965 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2008), 105–107; Eduardo Bonilla-Silva, Racism without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Inequality in America (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2022).

- Robert S. Browne, “Wealth Distribution and Its Impact on Minorities,” Review of Black Political Economy 21, no. 3 (Winter 1993): 116; Henry S. Terrell, “Wealth Accumulation of Black and White Families: The Empirical Evidence,” Journal of Finance 26, no. 2 (May 1971): 363–377.

- Thomas B. Edsall, “Whatever Happened to ‘Every Man a King’?,” New York Times, February 11, 2014; John H. Cushman Jr., “Russell B. Long, 84, Senator Who Influenced Tax Laws,” New York Times, May 11, 2003.

- Thomas B. Edsall, “Whatever Happened to ‘Every Man a King’?”; John H. Cushman Jr., “Russell B. Long, 84, Senator Who Influenced Tax Laws”; Howard, The Hidden Welfare State, 17; Brownlee, Federal Taxation in America, 173; Molly Michelmore, Tax and Spend: The Welfare State, Tax Politics, and the Limits of American Liberalism (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012); Faricy, Welfare for the Wealthy; Brown, The Whiteness of Wealth.

- Marissa Chappell, The War on Welfare: Family, Poverty, and Politics in Modern America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009), 52–53; Michelmore, Tax and Spend, 157; Long quoted in Howard, Hidden Welfare State, 4; Jennifer Mittelstadt, From Welfare to Workfare: The Unintended Consequences of Liberal Reform, 1945–1965 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005); Premilla Nadasen, Welfare Warriors: The Welfare Rights Movement in the United States (London: Routledge, 2005); William M. Rodgers III, “Race in the Labor Market: The Role of Equal Employment Opportunity and Other Policies,” Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 5, no. 5 (December 2019): 198–220, https://doi.org/10.7758/RSF.2019.5.5.10.

- Max Krochmal, Blue Texas: The Making of a Multiracial Democratic Coalition in the Civil Rights Era (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016), 2, 4, 6; Amy Sonnie and James Tracey, Hillbilly Nationalists, Urban Race Rebels, and Black Power: Interracial Solidarity in the 1960s–1970s New Left Organizing (Brooklyn, NJ: Melville House, 2021); Alex Beasley, Expert Capital: Houston and the Making of a Service Empire (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, forthcoming); Meg Jacobs, Panic at the Pump: The Energy Crisis and the Transformation of American Politics in the 1970s(New York: Hill and Wang, 2017).

- Michael McCarthy, Dismantling Solidarity: Capitalist Politics and American Pensions Since the New Deal (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2017); Sanford Jacoby, Labor in the Age of Finance: Pensions, Politics, and Corporations from Deindustrialization to Dodd-Frank (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2021); Brian Domitrovic, Econoclasts: The Rebels Who Sparked the Supply-Side Revolution and Restored American Prosperity (Wilmington, DE: Intercollegiate Studies Institute, 2009); Monica Prasad, Starving the Beast: Ronald Reagan and the Supply-Side Revolution (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2018). Previously, “capital formation” had referred to tangible and fixed assets, such as plants and equipment. In the 1950s and 1960s, corporate executives, economists, and business journalists invoked the term as they demanded that Congress reduce corporate taxes and accelerate depreciation schedules for corporations’ tangible assets. Box 90-287-92, box 329-77-96, box 329-88-39-73, box 329-88-39-74, box 329-88-39-207, box 329-88-39-318, box 329-88-186-12, box 329-88-186-26, Lloyd M. Bentsen, Jr., Papers, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin.

- Robert Collins, More: The Politics of Economic Growth in Postwar America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000); Michelmore, Tax and Spend; Brent Cebul, “‘They Were the Moving Spirits’: Business and Supply-Side Liberalism in the Postwar South,” in Capital Gains: Business and Politics in Twentieth-Century America, chap. 7, ed. Richard R. John and Kim Phillips-Fein (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016); Robert Gordon, The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The U.S. Standard of Living Since the Civil War (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016); Chappell, War on Welfare, 26–171; Lily Geismer, Left Behind: The Democrats’ Failed Attempt to Solve Inequality (New York: PublicAffairs, 2022), 3–11.

- Byrd Sr. quoted in Michael McCarthy, Dismantling Solidarity: Capitalist Politics and American Pensions Since the New Deal (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2017), 98; Greta Krippner, Capitalizing on Crisis: The Political Origins of the Rise of Finance (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012).

- Jefferson Cowie, Stayin’ Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working Class (New York: New Press, 2010), 7, 44, 140; Gary Gerstle, The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order: America and the World in the Free Market Era (New York: Oxford University Press), 48–49; Lane Windham, Knocking on Labor’s Door: Union Organizing in the 1970s and the Roots of a New Economic Divide (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017), 2–7; Nancy MacLean, Freedom is Not Enough: The Opening of the America Workplace (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008); US Department of Commerce, Social and Economic Status of the Black Population in the United States, report no. P23-54 (Washington, DC: Bureau of the Census, July 1975), 25, https://www.census.gov/library/publications/1975/demo/p23-054.html; Moritz Kuhn, Moritz Schularick, and Ulrike I. Steins, “Income and Wealth Inequality in America, 1949–2016,” Journal of Political Economy 128, no. 9 (September 2020): 26–29, https://doi.org/10.1086/708815; Maury Gittleman and Edward N. Wolff, “Racial Differences in Patterns of Wealth Accumulation,” Journal of Human Resources 39, no. 1 (Winter 2004): 193–227, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3559010; and Patrick Bayer and Kerwin Kofi Charles, “Divergent Paths: A New Perspective on Earnings Differences Between Black and White Men Since 1940” (working paper, no. 22797, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, November 2016, revised September 2017), https://www.nber.org/papers/w22797; Linda Faye Williams, The Constraint of Race: Legacies of White Skin Privilege in America (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2003), 146, 152.

- Alexis Marcus, Bernard E. Anderson, Duran Bell, Robert S. Browne, Vernon Dixon, Karl D. Gregory, and J. H. O’Dell, “An Economic Bill of Rights,” Review of Black Political Economy 3, no. 1 (1972): 1–41, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03040511; and David Stein, Fearing Inflation, Inflating Fears: The Civil Rights Struggle for Full Employment and the Rise of the Carceral State, 1929–1986 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, forthcoming); Eileen Shanahan, “Tax Aide Favors Top Rate of 35 Percent,” New York Times, June 2, 1972.

- John A. Lawrence, The Class of ʼ74: Congress After Watergate and the Roots of Partisanship (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018).

- Hearings before the Subcommittee on Taxation and Debt Management of the Committee on Finance, U.S. Senate, 95th Congress, 2nd Session, June 28 and 29, 1975, 14, folder “Taxation-Capital Gains 1970s,” box 27, Record Group 1.12, NYSE archives.

- Hearings before the Subcommittee on Taxation and Debt Management of the Committee on Finance, U.S. Senate, 95th Congress, 2nd Session, June 28 and 29, 1975, 70.

- Hearings before the Subcommittee on Taxation and Debt Management of the Committee on Finance, U.S. Senate, 95th Congress, 2nd Session, June 28 and 29, 1975, 73–74.

- Although they generated a fortune in fees for fund custodians and administrators, and a deluge of commissions for bankers and brokers, institutional investors like pensions funds upended the nation’s securities markets in the 1970s. Fund managers demanded discounts on the commissions charged on their trades, the abolition of rules prohibiting them from purchasing seats on the nation’s exchanges, and influence over the design of new computer-based market infrastructures. Put simply, the rapid ascent of these institutional investors challenged the self-regulating arrangements that New Deal reforms had conceded to the financial securities industry, particularly to the NYSE. John Ehmann, “Pension Fund ‘Socialism’ and the Future of the American Economy,” CrossCurrents 27, no. 4 (Winter 1977–78): 42–136, https://www.jstor.org/stable/24458347; Peter Drucker, The Unseen Revolution: How Pension Fund Socialism Came to America (London: William Heinemann, 1976); Randy Barber and Jeremy Rifkin, The North Will Rise Again: Pensions, Politics, and Power in the 1980s (Boston: Beacon, 1978); McCarthy, Dismantling Solidarity, 16, 77, 86, 145, 168; Devin Kennedy, Virtual Capital: Computing Power in the US Economy, 1947–1987 (New York: Columbia University Press, forthcoming).

- “House Panel Seems Sure to Approve Cut in Capital Gains Tax Rate Despite Carter,” New York Times, June 12, 1978.

- Gerstle, Neoliberal Order, 54; MacLean, Freedom Is Not Enough, 33–105, 108–291; Ellora Derenoncourt, “US Inequality Data,” https://sites.google.com/view/ellora-derenoncourt/us-inequality-data. The effective federal tax rate refers to the percentage of income actually paid in income taxes (that is, less any tax expenditures, deductions, credits, etc.). See figures 10.4 and 10.5 in Piketty, Capitalism and Ideology, 423, 453, http://piketty.pse.ens.fr/fr/ideology.

- Wendy Warren, New England Bound: Slavery and Colonization in Early America (New York: Liveright, 2016); Ian Baucom, Spectres of the Atlantic: Finance Capital, Slavery, and the Philosophy of History (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005); Calvin Schermerhorn, The Business of Slavery and the Rise of American Capitalism, 1815–1860 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2015); Edward E. Baptist, The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism (New York: Basic, 2014); Sven Beckert and Seth Rockman, eds. Slavery’s Capitalism: A New History of American Economic Development (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016); Walter Johnson, Soul by Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999); Walter Johnson, River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom(Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2013); Joshua Rothman, The Ledger and the Chain: How Domestic Slave Traders Shaped America (New York: Basic, 2021); Daina Berry, The Price for Their Pound of Flesh: The Value of the Enslaved, from Womb to Grave, in the Building of a Nation (New York: Penguin, 2017); Walter Johnson, St. Louis and the Violent History of the United States (New York: Basic, 2020); Cheryl Harris, “Whiteness as Property,” Harvard Law Review (June 10, 1993); Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (New York: Liveright, 2017); Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, Race for Profit: How Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Homeownership (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019); Mehrsa Baradaran, “Jim Crow Credit,” Legal Studies Research Paper Series No. 2021–51 (Irvine: School of Law, University of California, Irvine, May 2019); Mehrsa Baradaran, The Color of Money: Black Banks and the Racial Wealth Gap (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2017); Robin L. Einhorn, American Taxation, American Slavery (University of Chicago Press, 2008).

- US Department of the Treasury, “Tax Expenditures FY2024” (US Department of the Treasury, Washington, DC, October 2022), https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/tax-policy/tax-expenditures; CBO, “The Distribution of Major Tax Expenditures in 2019” (CBO, Washington, DC, October 2021); CBO, “Budget and Economic Outlook: 2022–23” (CBO, Washington, DC, May 2022), https://www.cbo.gov/publication/58147#_idTextAnchor186.