Two weeks ago, President Trump tweeted that a future Democratic president risked impeachment “without due process or fairness or any legal rights. All Republicans must remember what they are witnessing here—a lynching.”

Trump’s claims to victimhood are absurd. He is a wealthy white man and President of the United States; lynchings targeted and killed vulnerable black men. Trump’s claim is both a clear strategic effort to present impeachment as unfair and a transparent claim to victimhood that is more tightly bound up with lynching than the president knows.

According to the Equal Justice Initiative, more than 4,000 African Americans were lynched between 1877 and 1950, a number that would jump exponentially if the timeframe was extended back to 1865 and forward to 1965. Lynchings often imitated legal hangings—the noose, the gathered crowd, the next-day account in the newspaper—but not always. They were sometimes major social events attended by thousands, and sometimes secretive undertakings. On some occasions law enforcement officers successfully fended off mobs, or too often, joined the mob and aided in the cover-up for the crime after the fact.

Were non-black people lynched? Yes. Asians were lynched on the West Coast, Latinx people in the Southwest. And white people were lynched, too, particularly white people still on their journey to the full protection of whiteness, such as Italian immigrants lynched in New Orleans in 1891 or Leo Frank, a Jewish man, lynched in Marietta, Georgia, in 1915. And “card-carrying” white southerners were lynched as well, by mobs wanting to make some claim to justice to explain themselves. For instance, in 1855, a mob left a note in a “business-like hand” on the body of their victim: “Merry Christmas and Happy New Year. To this tree hangs the body of John Lee. Until the packing of juries ceases this process of justice will be sought.”

Although we know from the work of journalist and activist Ida B. Wells-Barnett that lynching was not a response to crime, but rather a form of systematic racist violence that targeted black success and land ownership, we know, too, that the victims of lynching were tenant farmers, day laborers, textile workers, tobacco pickers, and farmhands. Often, they were arrested and jailed before their lynchings, paradoxically making them easy targets for the mob.

Trump’s peevish tweet tells us at least two things about lynching.

Trump’s peevish tweet tells us at least two things about lynching. First, it draws attention to the fact that a broad reading of lynching is important in understanding the trauma black people experienced in courtrooms during the Jim Crow era. As activists at the time noted, the way black people on trial—largely, black men—were treated in southern courtrooms amounted to legal lynchings. They were ineffectively defended by reluctant attorneys and received death sentences following hasty trials before all-white juries.

Here in North Carolina, our mandatory death penalty sent scores of black men to death row for burglary (14 executed in the twentieth century, all black) and rape (72 executed, 63 of them black). Sometimes, a mob waited outside the courtroom. At least once, the mob was inside the courtroom—in 1927, a Superior Court judge fired a pistol to protect a black defendant on trial for his life for the rape of a white woman. The jury knew their job: to convict, lest the mob turn its ire on them.

Second, even as lynchings showcased the lethal power of the white majority, they also revealed that majority’s acute sense of victimhood. “Everything is against me,” complains Tom Chaney in Charles Portis’s odyssey True Grit. So, too, complained the members of mobs, who, unlike their black victims, could vote and run for office, own property without fear of being driven from it or cheated out of it, more readily love and marry who they wished, walk or ride where they wanted, and have bad days in public.

“We are the true victims!” they cried as they loaded rifles, and mounted horses. “We must act if the law does not!” they roared as they raided the jail where their target was held. “We must defend civilization from this brute!” they yelled as they tortured their victim. Buoyed by their whiteness and permitted by the legal system to kill with impunity, white men brimmed with faith in their own victimhood.

The white members of mobs embraced both the power to kill without consequence—fewer than 1% of lynchings led to convictions—and the idea that the killing was an act of self-defense. Such claims recast the villain as hero, where each member of the mob viewed taking up arms as a defense of their southern homeland. According to this rationale, thugs had honor and the true threat was the person killed by the mob. Black victims were described in newspaper coverage as animals,—beasts who posed an existential threat to white humanity. The same newspapers decried lynchings as barbaric, even as they protected the identities of mob members and argued why the lynched person deserved to be killed. They called those who were lynched monsters— “the brute,” “the beast”—and vividly detailed the crime they allegedly committed.

The idea of victim-as-aggressor not only justifies the horrific violence inflicted on them, but also explains away grotesque acts of cruelty. If people invade your country, threaten your way of life, endanger women and children, then of course they should be harassed, insulted, deported. On the other hand, when your success is in doubt, your political opponents are staging a lynching, or, as we recall from Clarence Thomas’s Supreme Court confirmation hearings, a “high-tech lynching.”

When we flip reality and make perpetrators the victimized party, our political process, our moral imagination, our very society becomes nightmarish.

When we flip reality and make perpetrators the victimized party, our political process, our moral imagination, our very society becomes nightmarish. Those who are struggling become a creeping threat. The most powerful become the most maligned. Racist resentment becomes righteous anger. Timid efforts to tamp down corruption become hysterical witch hunts. And so it is in the Trump campaign’s latest ad, which imagines the impeachment process as an effort to silence a righteous majority—“We are being silenced! You will not replace us!”

Witness this moment as southern history is manipulated in service of maligned power.

Seth Kotch, assistant professor of digital humanities, conducts research in modern American history (specifically the social history of criminal justice), digital humanities, and oral history. His book, Lethal State, was published by UNC Press in February 2019. Lethal State explores the history of the death penalty in North Carolina from its colonial origins; to its use during Reconstruction, Redemption, and Jim Crow; to its relationship to lynching; to its decline in the 1940s and 1950s; and to its resurgence in the 1970s as part of the backlash against the civil rights movement.

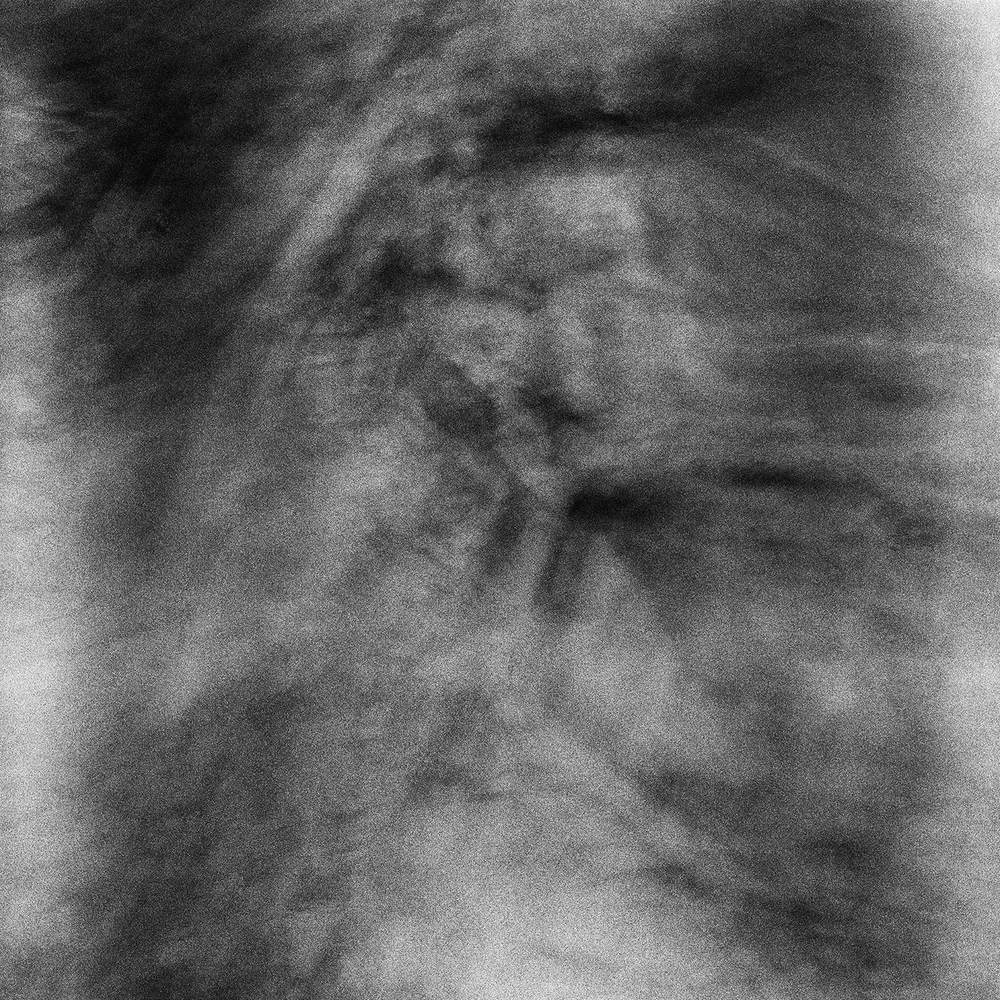

Gesche Würfel is a visual artist and Teaching Assistant Professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her work has been exhibited, published, and awarded internationally. One of her recent projects, “At the Hands of Persons Unknown”, examines how trees have been silent witnesses to the lynching of women in the United States.

Header image: Gesche Würfel, untitled 8 (2015), from “At the Hands of Persons Unknown.”NOTESFurther Reading:

Ida B. Wells-Barnett, A Red Record

Elijah Gaddis and Seth Kotch, Lynchings in North Carolina

Seth Kotch, Lethal State: A History of the Death Penalty in North Carolina

Kidada E. Williams, They Left Great Marks on Me: African American Testimonies of Violence from Emancipation to World War I