“The local townsfolk do not like mountain music. They can’t stand to listen to it. They buy Benny Goodman, Guy Lombardo, etc.” The typewritten missive in my hand, dated September 8, 1937, location Harlan, Kentucky, described, with no small dose of disdain, the musical predilections of residents in the region. It was mid-August in Washington, D.C., and I was hunched over a table in the frigid air-conditioned reading room of the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress, scouring paper after paper, folder after folder, box after box of documents like this, along with recorded discs, photos, and handwritten address books, etched with the names of fiddlers and ballad singers and their approximate locales. I was searching for a specific name in the margins, a note scrawled on some hotel stationery, a sign.

These were documents from Alan Lomax’s 1937 recording trip to Eastern Kentucky, when, at the age of twenty-two, under the auspices of the Library of Congress, he and his wife Elizabeth set off for the coal fields, the trunk of their Studebaker packed with a Presto disc-recorder and a stack of blank discs, in search of traditional musicians. Two months later, they returned to the very place where I was sitting with over thirty-two hours of recordings—fiddle tunes and blues, Pentecostal hymns and murder ballads, work songs and lullabies, breakdowns and children’s games; absent, however, were the popular songs Lomax scorns above, ostensibly learned from radio and records that were becoming readily available in the area. Among what he did record were sounds of those now held up as masters of the old-time tradition: fiddler Bill Stepp (whose recorded performance of “Bonaparte’s Retreat” would, through Aaron Copland’s interpretation, later reach millions of Americans in the “Beef: It’s What’s For Dinner” commercials), and banjo players Richard Whitely and Walter Williams.

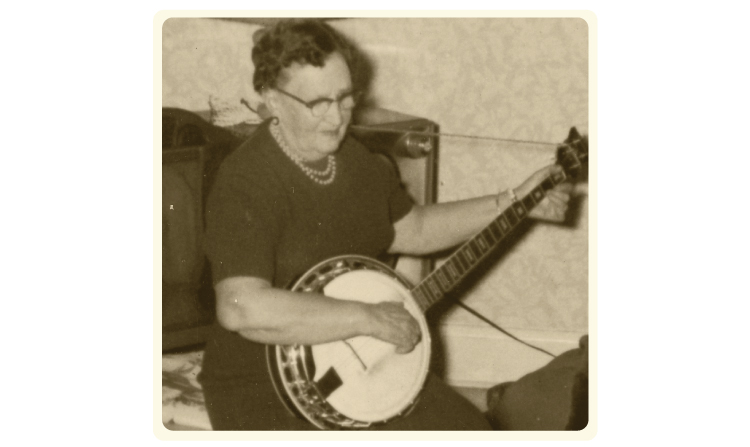

But neither Lomax nor Stepp were the subject of my search. I was looking for another name—that of a friend, neighbor, and music partner of those greats, but one who did not achieve their same renown. It’s the name of a banjo player, a harp blower, a songwriter, radio show host, band leader, sheriff, postmaster, general store manager, hotel owner, pig farmer, wife and mother, known in her day as “Queen of Magoffin County”: Nora E. Carpenter.

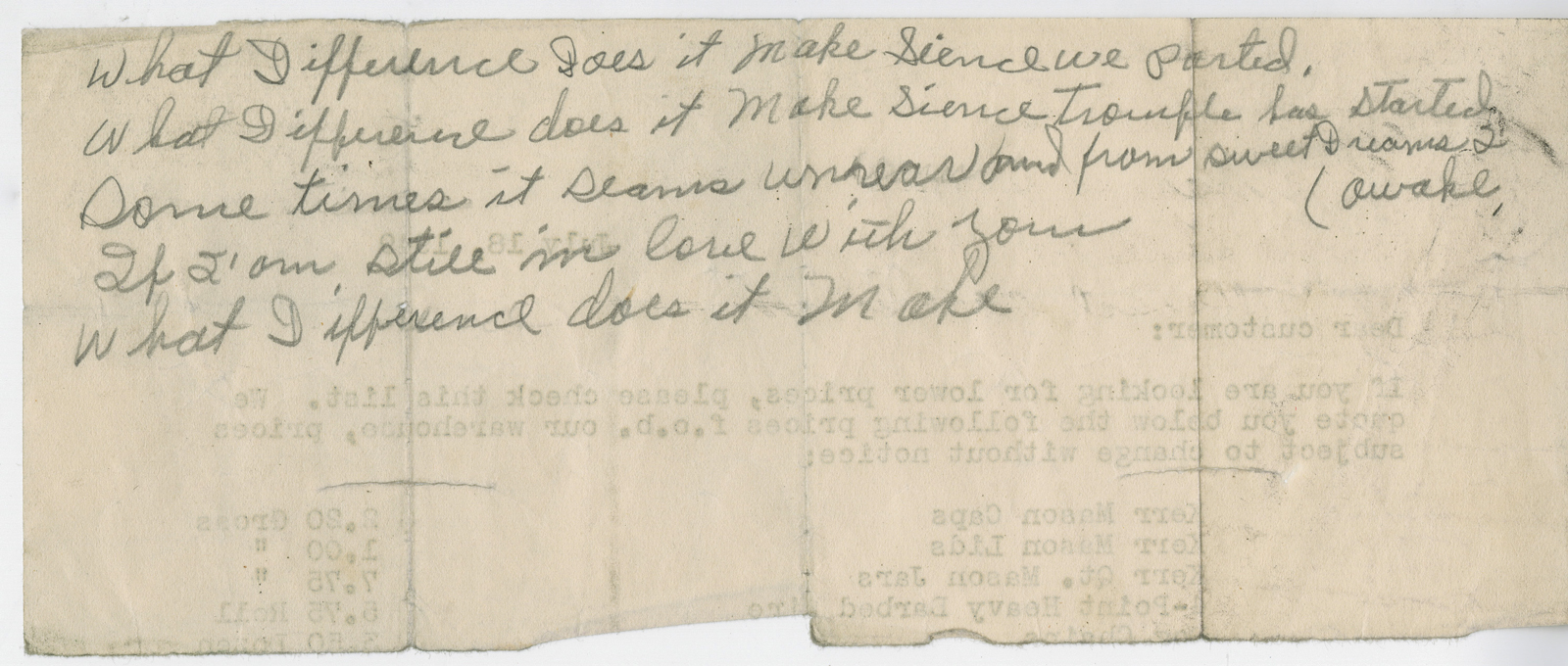

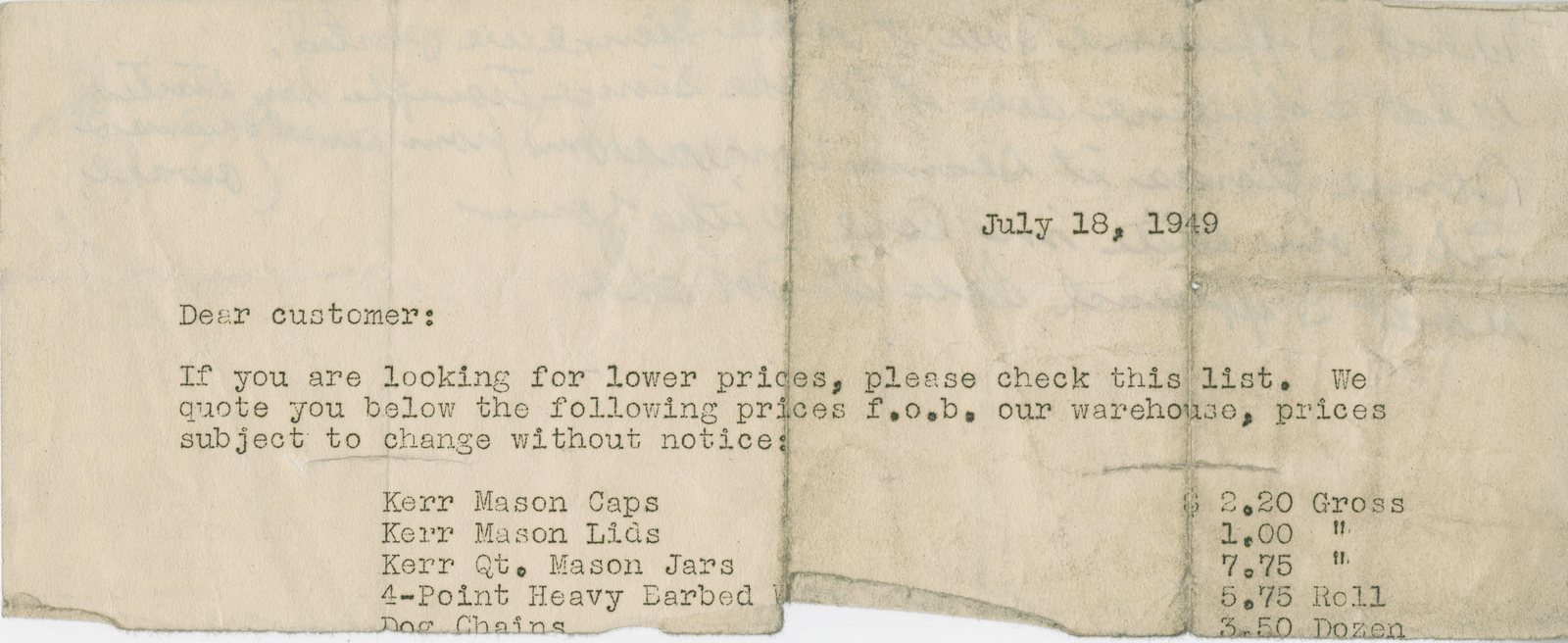

I had spent the month prior in Berea, Kentucky, as a fellow at the Berea College Appalachian Sound Archives, studying the collection of Ms. Nora Carpenter (1888–1975). From Salyersville, the county seat of Magoffin County, Kentucky, Carpenter was a stronghold in her community. She had a daily radio show with her band “Big Mama (sometimes listed as “Hot Mama”) and the Half Mountain Hot Shots” on WSIP out of Paintsville, owned and ran a twenty-six room downtown hotel with her husband that, along with offering lodging for out-of-town guests, was a community gathering place, the lobby providing the setting for many picking parties and bean-shucking gatherings. She played music not only with those Magoffin County musicians mentioned above, but also a mandolin player by the name of Bill Monroe when he came to town to perform at the Star Theater. She wrote extensive transcripts of her repertoire that included ballads, early country songs, hymns, and her own compositions that documented local events and personal experiences, all etched on the back of hotel stationery, hunting safety exams (Carpenter was known as a crack shot), letters, grocery receipts, and other scraps. Carpenter also made home recordings of herself and her band, some of which she sent to relatives who had moved away. These transcripts and a handful of recordings made by her family late in her life make up what is now Carpenter’s archival collection, which was donated to the college by her daughters in 2007.1

During my month in Eastern Kentucky, I immersed myself in Carpenter’s collection, interviewing family members, reading what little had been written about her already, and visiting related sites in Salyersville—the remains of the old Hotel Carpenter with its mural of Carpenter and her husband Morgan Green on the side, her old log cabin general store reconstructed in relatives’ backyard, and her grave, but it was almost too late to glean much more. Only one of her children is still living, and only a granddaughter and great granddaughter were willing and able to talk with me. Most Salyersville residents knew who she was, but had few specifics to share. In my research trip to the American Folklife Center, I was now attempting to put Carpenter in context, find a connection between her and a greater narrative of American traditional music, and determine what broader import a study of her might have. In his book The Beautiful Music All Around Us, in a chapter that traces the origins of “Bonaparte’s Retreat,” Stephen Wade suggests that the Lomaxes may have stayed at the Hotel Carpenter on their 1937 trip, and Carpenter likely tipped Alan off to Bill Stepp, adding, “One way or another, through blood ties, marriages, and social contract, the Salyersville players were intertwined in one another’s lives.” (Carpenter and Stepp were longtime music partners and Carpenter continued to visit him after he moved to northern Indiana in the early 1940s.) After a daylong search through all of the Lomax’s boxes, correspondence, and every disc sleeve from that trip, however, I found nothing that suggested any of those ties.2

I wondered if in devoting so much attention to linking Carpenter to her male counterparts and Lomax’s fieldwork, I was obscuring the real lesson that Carpenter’s body of work had to teach.

Stepping out into the D.C. humidity, disappointed with seemingly little to show for the day, I began to consider if perhaps I was missing the point in my quest to embed Carpenter within a greater context and narrative. Naturally, I was doing my due diligence as a researcher, but I wondered if in devoting so much attention to linking Carpenter to her male counterparts and Lomax’s fieldwork, I was obscuring the real lesson that Carpenter’s body of work had to teach. While Carpenter was not inscribed into existence by Lomax or other folklorists during her lifetime, and with just brief mentions of her in written work by Stephen Wade and in my personal communication with vernacular music scholars Bob Carlin and Bruce Greene, her memory is preserved because she extensively documented her regular creative work and process.

Since that discouraging day at the library, I’ve come to view the Nora E. Carpenter Collection as a unique example of the work of a woman engaged in creative documentation of her own life and community. Carpenter’s self-documentation, including both texts and recordings, is particularly unusual because it was undertaken by a woman. While many women kept written records, home audio recordings were uncommon, expensive, and rarely made by women in the mid-twentieth century. Carpenter’s ability to record was partially facilitated by her family’s financial circumstances. She and her husband were a relatively prosperous family in the region. He served as president of the bank, and although the Hotel Carpenter may have been an important source of income at one point, in its later years it was essentially kept open as a hobby and community gathering place. Carpenter had hired help who took on much of the food preparation for her family, or they ate meals at the hotel. Those financial circumstances afforded Carpenter the time and resources to pursue her music, but her husband was also supportive of her taking on this type of non-traditional role. Those privileges aside, Carpenter also had the sheer wherewithal to document herself. In turn, her daughters and granddaughters saw the value in her work and had the foresight and generosity to donate it to the Berea College Sound Archives.

Archival collections like Carpenter’s are not common, nor are they most accessible or easily discernible. Because of Carpenter’s community and family-based audience, fluid notions of authorship, and lack of confirmed connections with an existing narrative of Eastern Kentucky music at the time, her contributions are difficult to position within a broader historical context. I’ve come to approach that difficulty not as a statement of value, but as a more accurate reading of the true motivation of Carpenter’s self-documentation project. Her songwriting, recording, and act of creative documentation were a humble yet extensive daily endeavor. She borrowed lines from other songwriters and shared hers with her audiences. She learned songs off the radio and via interactions with her fellow local musicians. Her collection has its own gaps, as all archival collections do, but it presents a rare glimpse into the self-curated life of an Eastern Kentucky musician who exhibited a documentary agency seldom encountered in archival research of mid-twentieth-century traditional music and its intersection with regional popular music.

The Collection

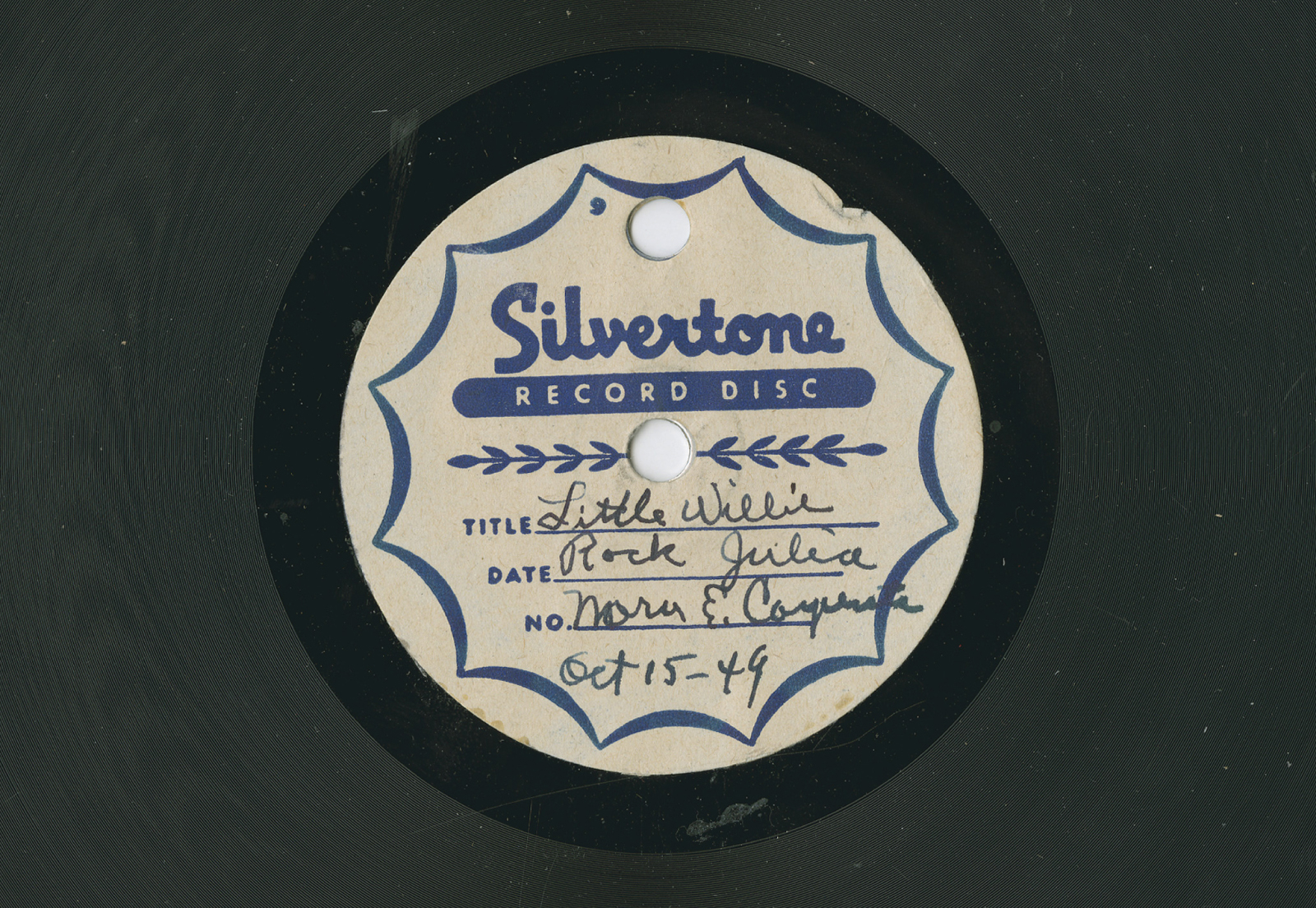

The Nora E. Carpenter Collection of ephemera and lyric songbooks comprise two archival boxes with over 300 typed or handwritten lyric sheets of Carpenter’s own songs and other traditional and popular tunes in her repertoire. The recordings in her collection fill another box, with eleven reel-to-reel audio tapes, seven of which she recorded in the 1960s and 1970s when she was in her eighties, as an effort to preserve her repertoire for family members who had moved away. While I was working on the project, Carpenter’s granddaughter Valerie Patrick uncovered over fifty additional home recorded disks of Carpenter and her band, predating what the collection had by at least twenty years, and presenting an audio record of Carpenter’s musicianship at the peak of her ability.

While Carpenter’s scrapbooks contain dozens of original songs—those she wrote “from scratch,” like “Wreck of the Floyd County School Bus,” “Death of Brother Owens,” and “Groanin’ Moanin’ Groanin’ Blues”—she often shifts around the lines in others’ songs, both standards and those of other musicians, renames them, and calls them her own. In her written lyric transcriptions, if a song is not her original work, Carpenter signs it, “Written by Nora E. Carpenter,” or “Written by N.E.C.” If she composed a song, or it bears any original content no matter how subtle the changes, she signs it “Written and Composed by Nora E. Carpenter,” “Written and Composed by N.E.C.” or “Composed by Nora E. Carpenter.” Other songs—both those I clearly recognized from other sources and some I believe to be Carpenter’s originals—go unattributed. These inscriptions and the occasional lack of them, point to the ownership Carpenter asserted over songs, originals and otherwise, and communicates the agency she felt in curating her own repertoire. Regardless of whether Carpenter composed or “wrote” them, these songs enunciated something personal and powerful to her. By including them in her repertoire and inscribing her name to them, she conveys her connection to them and makes them her own. At the same time, the occasional missing inscription also suggests an informal approach to her still astute documentation. For Carpenter, transcribing song texts was a daily activity, intended as both an act and a record for herself, her family, and her community and did not necessarily have broader motivations.

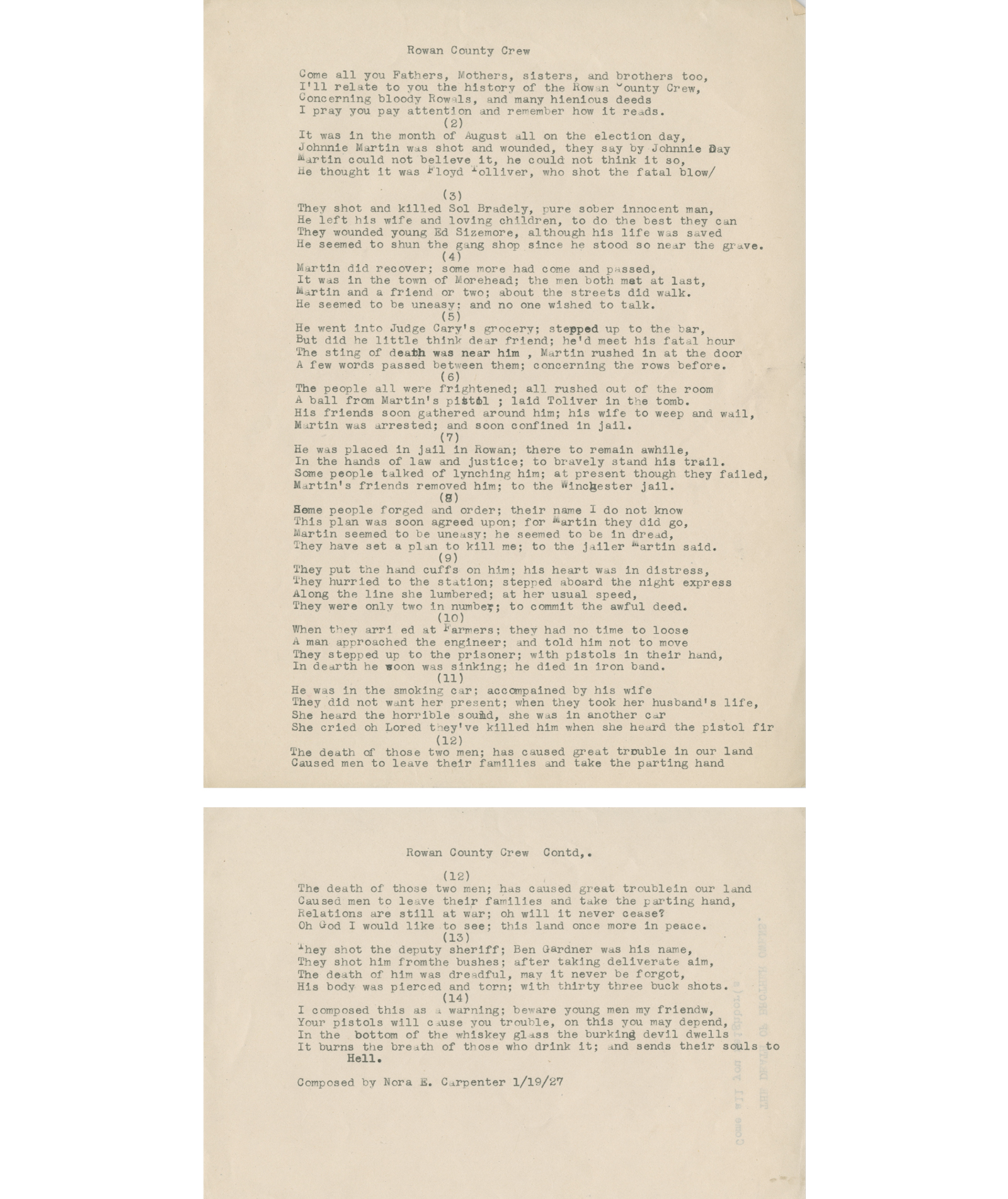

I identified one exception to Carpenter’s established precedent for inscription in the transcription of the song “Rowan County Crew,” which recounts the Tolliver–Martin family feud that took place in Rowan County, Kentucky, between 1884 and 1887. The song was written by James W. Day (also known as “Jilson Setters”) in 1918, and Ted Chesnut made the first known recording ten years later in May 1928. It was later recorded by Virginia banjo player Dock Boggs, whose version is now the best-known. The two transcriptions of the song in Carpenter’s scrapbook are dated January 19, 1927, predating the first known recording, and are signed “Composed by Nora E. Carpenter.” Aside from small stylistic differences, such as Carpenter’s opening line, “Come all you fathers, mothers, sisters and brothers too,” versus the more common “Come all ye young people, fathers and mothers too,” Carpenter’s lyrical transcription of the song is almost exactly that recorded by Chestnut and Boggs and transcribed by others from 1927 to present day. Indeed, Carpenter could have intended to write “Composed by” and, as she had done before, take credit for the song as her own. This would not be the only evidence of Carpenter slightly altering a popular or known song and crediting it to herself, but it would be an anomaly in that it bears very little original content in comparison to the other songs for which she takes credit. It also could have been a simple error.3

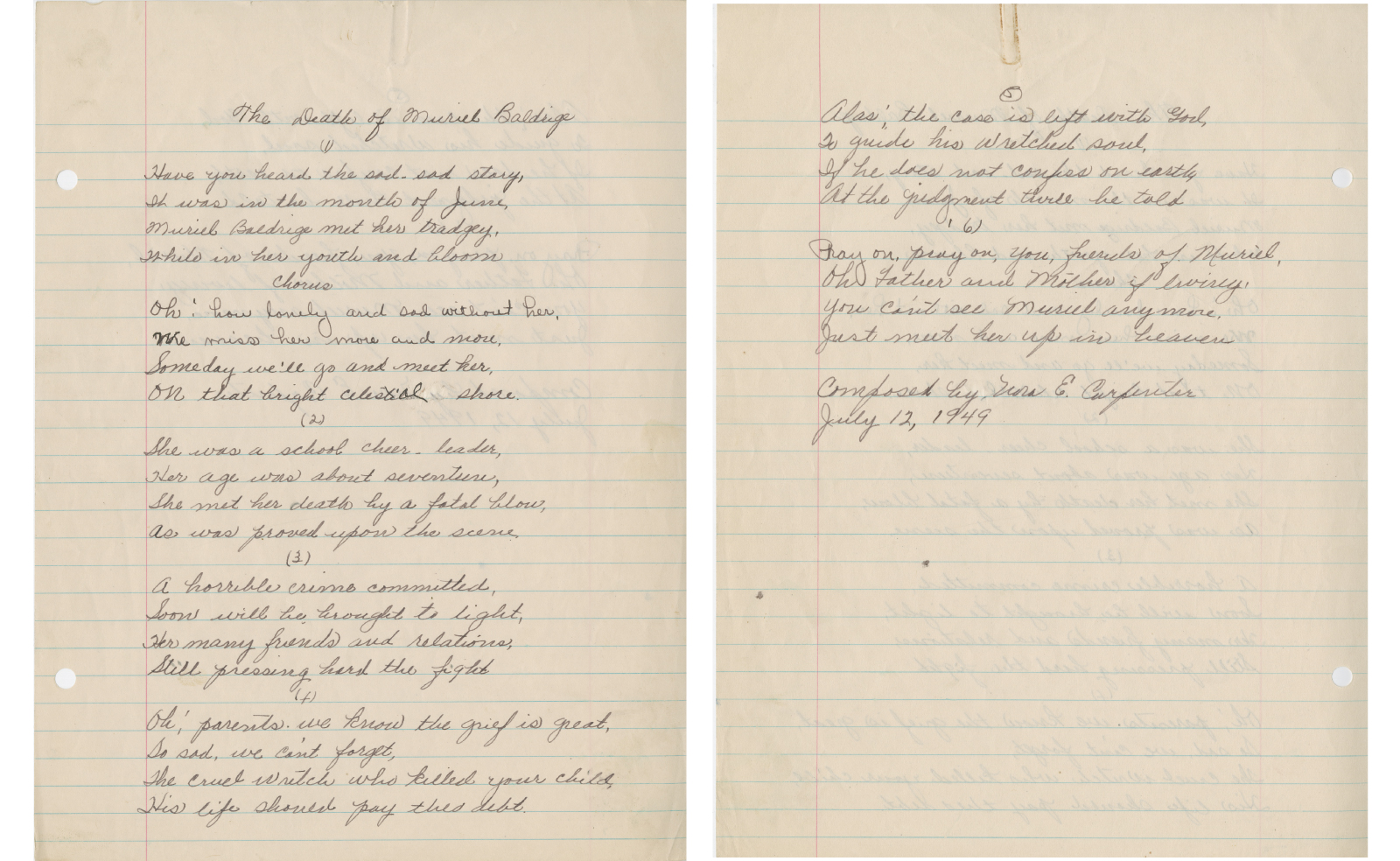

In 1949, Carpenter wrote “The Death of Muriel Baldrige,” about the still unsolved murder of a local Prestonsburg cheerleader. Carpenter seems to have written the only song about the event, and her granddaughter remembers accompanying her on a visit to Muriel’s parents to ask for permission to write it. Curiously, though, the date on Carpenter’s song lyrics, July 12, 1949, predates the date of the actual murder (July 27, 1949). Whether this is just a simple instance of recording the incorrect date (or mistyping a correct one), or whether this points to additional inaccuracies in Carpenter’s records, is hard to discern. As well as reinforcing Carpenter’s interest in preserving community history and memory through song and positioning herself as a storyteller in her community, this also illustrates how Carpenter’s idiosyncratic system differs from a formal archiving process. The dating of her song transcriptions may be gestural approximations and are less important than the retelling of the event and expression of a sentiment intended as a condolence for the community who experienced the tragedy. These discrepancies do not discount Carpenter’s credibility, especially considering the impressive body of work she produced. Human error is inevitable in any archival system, professional or amateur. But these instances are notable because they further problematize using mainstream notions of authorship and documentation to place Carpenter within a greater narrative. Carpenter eludes these predominant frameworks with definitive dates, times, and authorial assertions, and instead invents her own documentary notation. In a greater scope, this exemplifies a fluid notion of authorship that is perhaps curious by modern standards, though not altogether unusual in traditional music communities of Carpenter’s place and era. Carpenter’s work compels one to consider authorship and recordkeeping as shifting values that do not necessarily translate across culture and time.4

Carpenter’s work compels one to consider authorship and recordkeeping as shifting values that do not necessarily translate across culture and time.

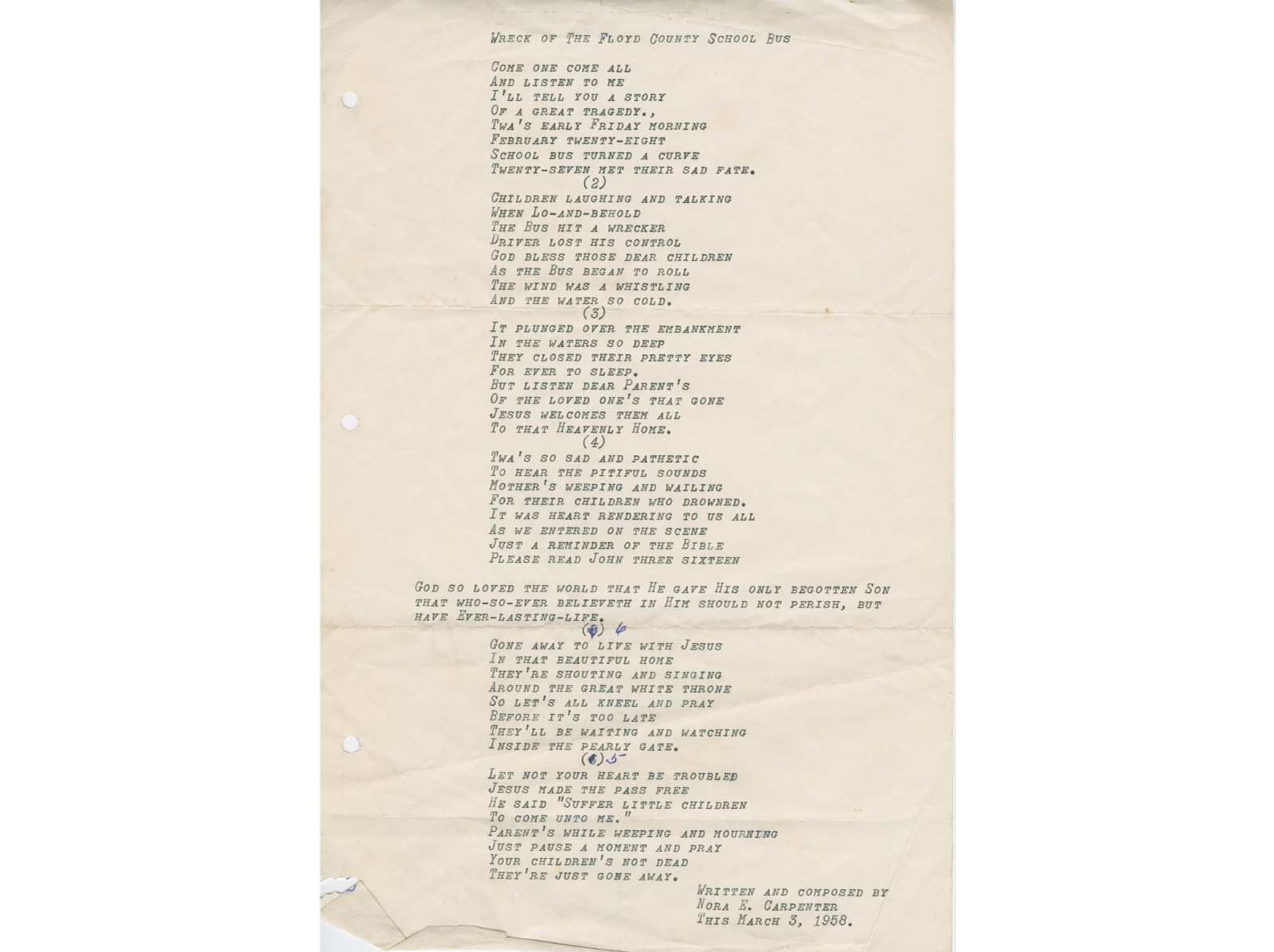

Examples of this fluid authorship are evident throughout Carpenter’s repertoire. On March 3, 1958, Carpenter wrote the song “Wreck of the Floyd County School Bus” about a tragic bus accident that claimed the lives of twenty-seven in Prestonsburg, Kentucky, the month prior. The accident is on record as the third deadliest school bus wreck in U.S. history and was well-known in Kentucky at the time. It was also eulogized in song by the Stanley Brothers (“No School Bus in Heaven,” 1958) and Ralph Bowman (“The Tragedy of Bus 27,” 1958), both of which received regional radio airplay. Carpenter’s version is a modal banjo tune with a melody reminiscent of the traditional “I Never Shall Marry,” a song that is also included in Carpenter’s transcriptions and recordings. While her tragic account bears some lyrical similarities to Bowman’s song, which is also included in Carpenter’s songbook, hers is notably different, and it is unclear whether Carpenter was prompted to write the song upon hearing Bowman and/or Stanley’s versions, or if it was directly inspired by the event itself. Either way, this existence of multiple accounts of the same event illustrates how Carpenter viewed her songwriting as part of a local and regional discourse and tradition of topical ballads. Even in Carpenter’s most original works, there is a clear common vernacular that challenges singular authorial boundaries.

Carpenter’s extensive scrapbooks of song transcriptions amount to a substantial body of work. In addition to the 300 lyric sheets in the Berea College archive, her daughter has at least two additional scrapbooks, not included as part of the collection. The implied intertextuality between Carpenter’s songs and other records of daily life demonstrate how songs, songwriting, and the creative process were entwined with other crucial aspects of her daily life, no more or less important than correspondence with family members or friends. In fact, her recordings for family members who had moved away show that her repertoire was a valued aspect of her familial communication. It was another form of connection, a coupling of the quotidian with the creative. Together, Carpenter’s scrapbooks and recordings represent an evocative documentation of daily life as a mother, business owner, social person, musician, and artist.

Carpenter’s annotations and use of songs to speak for her reveals her intimate relationship with her repertoire.

The songs in Carpenter’s repertoire are effectively a curated grouping of original and sourced texts—the prominent genres being topical songs, gospel, hymn, ballad, local tragedy, family, loss of mother, death, work, war, and soldier’s death. These texts point to Carpenter’s personal values, her intended community audience, and cultural context. As her great-granddaughter Maren Bzdek commented in a personal correspondence, “Big Mama was intimidating, not particularly warm, but extremely sentimental.” The way Carpenter most readily expressed those sentiments was through song. The lyric sheets of these songs are often annotated with related personal thoughts, emotions, and dedications, further asserting ownership of her selected repertoire. What is particularly interesting about Carpenter’s scrapbooks is that there are numerous instances of the same song being copied over and over again. She seems to have called up certain songs when she felt they corresponded to a personal feeling or relationship. If she didn’t have a relevant song in her back catalog, she wrote a new one. For Carpenter, songs were an intimate, even diary-like outlet for creative communication, a powerful means of articulating connection, emotion, and identity. One such song, “Hospital Blues,” is annotated, “Up in the hospital & feeling so sick and alone”; another, “A Vacancy in My Heart,” dated February 10, 1959, is inscribed, “Up at [her youngest daughter] Cleorita’s babysitting so sad and lonely.” Carpenter’s annotations and use of songs to speak for her reveals her intimate relationship with her repertoire. This is evident in her textual annotations and in recorded dedications such as, “I want to do this in memory of my son—he always loved this song so good,” before playing “Sweeter Than the Flowers,” or in a spoken interlude addressed to her deceased husband in “Lost Love.” Carpenter’s repertoire was influenced by her family, friends, and bandmates and also conveys those important relationships.

The type of heteroglossia Carpenter employs with multiple utterances of song text and personal annotations was common at the time (and certainly persists today in mix tapes or playlists communicating love for the recipient or in social media posts of a song annotated with a personal message such as, “a perfect song for this rainy day” or “this is how I’m feeling right now”). Carpenter’s repertoire not only expressed something about her and her community, but it was also a collection of texts with which she was constantly in dialogue. For women of Carpenter’s time and place, this form of identity-crafting, self and familial documentation, and dialogic relationship with text was common—it occurred through song lyric transcriptions but also in annotations in a well-used cookbook or as dates and events inscribed in a family Bible. Specifically, folklorists have extensively studied the act of women keeping written song collections. Patricia Sawin’s work with Appalachian ballad singer Bessie Eldreth (1913–2001) via Sawin’s book Listening for a Life, in particular, parallels and has informed this project in many aspects.

Sawin and other scholars suggest that this form of song text documentation allowed women “to engage in sociable interaction focused on song texts for those who do not or cannot sing where others can hear them.” Carpenter’s songbooks were an important outlet for more private personal reflection and emotions that were not likely voiced publicly—particularly in some of her song annotations later in life that express her loneliness, sadness, or longing for her deceased husband. For Carpenter and her family, music also carried a familial and community identity that she felt necessary to be preserved and remembered, particularly by those who were no longer geographically part of the community. Later in life when Carpenter had access to more accessible and transportable recording technology, she sent both tapes and transcripts of her repertoire to family that had left Eastern Kentucky for Arizona. But Carpenter was also unique in that she was allowed a performative outlet. Her daily radio show with her band was widely popular in Magoffin and Johnson Counties. Unfortunately, no tapes of her radio show exist, but one can imagine that through the daily show, Carpenter engaged in a dialogic relationship with her community through song. Her listeners undoubtedly made requests and gave her feedback on her performances, and she was able to bring her original compositions and song dedications and annotations to a public forum.5

As Carpenter’s most musically productive period occurred from the late 1930s through the mid 1960s, she is situated at a moment in time in traditional Appalachian music when phonograph records and songs learned from the radio were being incorporated as part of the tradition. Sawin expands on this in her work with Bessie Eldreth, “Eldreth’s repertoire demonstrates perfectly the realization that people in the southern mountains had never been as isolated from American popular culture as the ballad collectors and settlement school teachers wanted to believe.” Like Eldreth’s, Carpenter’s repertoire is indicative of this blending of original compositions (many of which are inspired by traditional songs) with popular hymns and gospel, songs from the Grand Ole Opry, which she listened to religiously every week, songs that she likely picked up from other local musicians and touring acts who passed through Salyersville to play at the Star or Alamo Theaters, or that she remembered from her childhood. While Carpenter’s influences can be sourced both inside and outside of the tradition, it seems that Carpenter had no preference for one over the other. Her repertoire is a hybrid, and she appears to be more interested in her own relationship to the song and what it expresses to and for her, rather than its origins.6

This catholic approach to repertoire is in stark contrast to the curatorial interest of Lomax and other professional folklorists, who perceived any influence from the radio, records, or “outside sources” as an infiltration or desecration of traditional mountain music. This may have been one of the reasons Lomax, who was “somewhat disappointed as many of the musicians he was encountering mainly sang songs that he considered too new and unimportant to document,” did not record Carpenter—her repertoire contained too much popular modern influence. Like all documentarians, Lomax was obliged to make editorial decisions, but acknowledging his preferences and shortcomings makes room for narratives and archival collections that employ other documentary methodologies.7

Carpenter undertook what we might consider a meta-folklore project, with an alternative community- and family-based approach to documentation. This was not documentary work done by an outsider on a brief visit to town for an outside audience at the Library of Congress, nor was it curated to include only the “pure” traditional material, uninfluenced by radio or recorded music; rather, it was a singular, intimate project, conducted over a period of at least forty years, and intended for Carpenter herself, her family, and her community. The act of documentation became part of her creative project. Carpenter’s documented materials, coupled with additional information from family and community members and what little I could glean from other outside sources, communicates valuable information about her self-construction, fluid notions of authorship in traditional music, politics of memory and accrediting that run counter to prevailing notions, and our understanding of the musical influences on Eastern Kentucky and broader Appalachia in the post-recording “boom” of the 1920s when recorded music and radio broadcasts achieved wider distribution in the region.

Emily Hilliard is the West Virginia state folklorist, based at the West Virginia Humanities Council. She earned her MA in folklore from the University of North Carolina in 2011 and was a Berea College Appalachian Sound Archive Fellow in 2014. See more of her work at emilyehilliard.com.NOTES

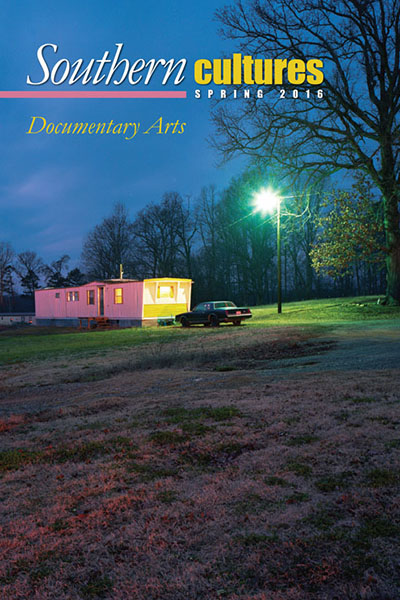

Photographs and archival images courtesy of the Nora Carpenter Traditional Music Collection, Berea College Special Collections and Archives, Berea, K.Y. All digitized recordings from the Nora E. Carpenter Collection can be found in the Digital Collections of the Berea College Special Collections and Archives.

- Bill Monroe played at the Salyersville Star Theater often in the 1940s and 1950s and stayed at the Hotel Carpenter when in town. According to Carpenter’s great-granddaughter Maren Bzdek, he played “Trace Your Little Footprints in the Snow” in Carpenter’s honor during a concert at the Kentucky Theater in Lexington, shortly before he passed away. Maren Thompson Bzdek, “The Carpenter’s Life at Swampton,” Life Along the Licking River, Volume 1, 339–349.

- See Stephen Wade, The Beautiful Music All Around Us: Field Recordings and the American Experience (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2012), 35–36; and Bob Carlin, “Alan Lomax—The 1937 Kentucky Field Recordings,” Bluegrass Unlimited 38, no. 11 (May 2004): 68–72; Wade, The Beautiful Music All Around Us, 35.

- Also known elsewhere as “Rowan County Feud,” “Rowan County Trouble,” or “Rowan County Tragedy”; “Rowan County Crew (Trouble, or Tragedy), The [Laws E20],” The Traditional Ballad Index Version 3.6, accessed July 17, 2015, http://www.fresnostate.edu/folklore/ballads/LE20.html; This appears in a version transcribed by John and Alan Lomax from Mr. and Mrs. George White in Grand Saline, Texas, 1937; John A. Lomax and Alan Lomax, Our Singing Country: Folk Songs and Ballads (New York: Dover, 1941), 324–326.

- In her lyric transcripts Nora spells Muriel’s surname “Baldrige.” Other sources, including the July 15, 1949 Chicago Tribune and other local newspapers, spell it “Baldridge.” Different covers of Michael Crisp’s 2011 book Murder in the Mountains: The Muriel Baldri(d)ge Story, spell it both with and without the second “d”; Interview with Selma Carpenter, July 29, 2014, Salyersville, Kentucky.

- Patricia Sawin, Listening for a Life (Logan: Utah State University Press, 2004), 188; One such tape offhandedly refers to country musician Buck Owens, who was apparently a relation; The popularity of Carpenter’s daily radio show was articulated by family members and community members I interviewed during my stay in Eastern Kentucky. In an email correspondence, Carpenter’s relative Scotty Patrick noted, “The first time I really thought about her other than as a relative, was when she appeared live on WSIP, a new ready [radio] station that had just opened in neighboring Paintsville, KY . . . Over 30 people, including myself, went to the station to watch her play live on the radio as ‘Big Mama and the Half Mountain Hot Shots.’” One panel of a mural painted on the exterior of Carpenter’s former hotel depicts her playing with her band on the radio, and her family members have saved flyers of the show. I attempted to search for any tapes that existed from the broadcast, but upon speaking with Dan Lyons, a current radio host at WSIP and the unofficial station historian, I learned that the shows were evidently not taped (he reported that this lack of documentation was typical at the time).

- See D. K. Wilgus, “An Introduction to the Study of Hillbilly Music,” Journal of American Folklore 78, no. 309, Hillbilly Issue (July–September, 1965): 195–203; Sawin, Listening for a Life, 160.

- Aside from his tastes and desire for the unmarred “authentic” traditional musicians, there also may have been a number of other circumstantial reasons why Nora Carpenter doesn’t make it into Alan Lomax’s notes or recordings from his 1937 trip. Renowned Magoffin County fiddler John Morgan Salyer, for example was notoriously absent from the recordings from this fieldwork; he was away on a pipefitting job in Knoxville, Tennessee, at the time.