1. Abiding Metaphors

When I was three years old, I nearly drowned in a hotel pool in Mexico. My earliest memory is of what seemed a long moment, as if I were suspended there, looking up through a ceiling of water, the high sun barely visible overhead. I do not recall being afraid as I sank, only that I was enthralled by what I could see through that strange and wavering lens: my mother, who could not swim, leaning over the edge—arms outstretched—reaching for me. She was in the line of the sun and what she did not block radiated around her head, her face like an annular eclipse, dark and ringed with light.

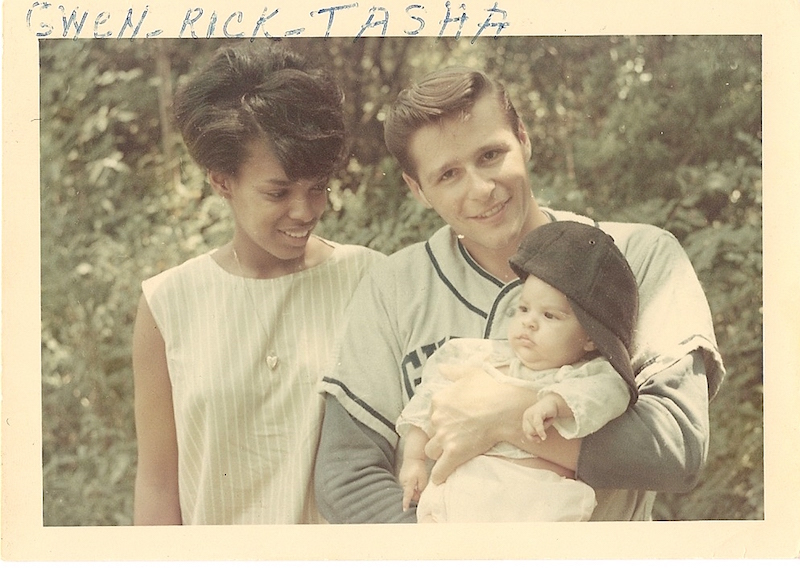

It was 1969, a trip with my parents—my black mother, my white father. Looking back now I can see this is where it begins, what Robert Frost insisted was a necessary education, a proper poetical education in the metaphor, and the establishment in my consciousness of the abiding metaphors by which my work as a poet is always influenced. Beyond my vivid memory of nearly drowning—an image to which I’ll later return—only one other image of the trip remains: a photograph. In it, I am alone, there are mountains in the distance behind me, and I am sitting on a mule.

In his essay “Education by Poetry,” Robert Frost wrote: “What I am pointing out is that unless you are at home in the metaphor, unless you have had your proper poetical education in the metaphor, you are not safe anywhere. Because you are not at ease with figurative values: you don’t know the metaphor in its strength and its weakness. You don’t know how far you may expect to ride it and when it may break down with you. You are not safe in science; you are not safe in history.”

Like Frost, my father believed in the necessity of a thorough grasp of figurative values. He was a poet, and had begun my education in metaphor as early as I can remember. It was his idea to place me on the back of the mule—a linguistic joke within a visual metaphor: the sight gag of a mixed-race child riding her namesake, animal origin of the word mulatto. It was my father, too, who—perhaps oblivious to his own metaphors of animal husbandry—referred to me as a crossbreed in one of his poems, who taught me the phrase Heinz 57, a term for someone racially mixed. “All mixed up,” he’d said. Of the many photographs from my early childhood only this one suggests what I’d come to understand that each of my parents wanted me to know.

The picture represents my father’s desire to show me the power of metaphor: how imagery and figurative language can make the mind leap to a new apprehension of things; that we might harness, as with the yoke of form, both delight and the conveyance of meaning; that language is a kind of play with something vital at stake.

In my work I turn often to photographs and other documentary and archival evidence, seeking to describe not only the “luminous details” of history, to borrow Pound’s phrase, but also to focus in on what Roland Barthes referred to as the “punctum”—the thing that pricks you, wounding you into recognition. If there is a luminous detail, a punctum, in the photograph I described, it is not the fringe of lace on my sock, like an eyelash around my ankle, nor the delicate smocking on the bodice of my dress, but the way—simultaneously, it seems—that the mule and I have turned our heads to face the camera. This is what takes me out of the frame to contemplate the circumjacent conditions of the historical moment, of law, of received knowledge and knowledge production, of science.

“Unless you are at home in the metaphor, unless you have had your proper poetical education in the metaphor, you are not safe anywhere.”

My mother had come of age in Mississippi during the era of Jim Crow and at the height of the Civil Rights Movement. She had grown up steeped in the metaphors that comprised the mind of the South—the white South—and thus had not missed the paradox of my birth on Confederate Memorial Day: a child of miscegenation, a word that entered the American lexicon during the Civil War in a pamphlet. It had been conceived as a hoax by a couple of journalists to drum up opposition to Lincoln’s re-election through the threat of amalgamation and mongrelization. When I was born, my parents’ marriage was illegal in Mississippi and as many as twenty other states in the nation, rendering me illegitimate in the eyes of the law, persona non grata. My father was traveling out of town for work so she made the short trip from my grandmother’s house to Gulfport Memorial Hospital, as planned, without him. On her way to the segregated ward she could not help but take in the tenor of the day, witnessing the barrage of rebel flags lining the streets, flanking the Confederate monument: private citizens, lawmakers, klansmen hoisting them in Gulfport and small towns all across Mississippi. The twenty-sixth of April that year marked the hundredth anniversary of Mississippi’s celebration of Confederate Memorial Day—a holiday glorifying the Lost Cause, the Old South, and white supremacy—and much of the fervor was also a display in opposition to recent advancements in the Civil Rights Movement, namely, the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts of 1964 and ’65.

Sequestered on the Colored floor, my mother knew the nation was changing, but slowly. She knew, as the figurative level of the photograph suggests, that I would have to journey toward an understanding of myself, my place in the world, with the invisible burdens of history, borne on the back of metaphor, the language that sought to name and thus constrain me. I would be both bound to and propelled by it. She knew that if I could not parse the metaphorical thinking of the time and place into which I’d entered, I could be defeated by it. You are not safe in science; you are not safe in history.

2. You Are Not Safe in History

Growing up in the Deep South I witnessed everywhere around me the metaphors meant to maintain a collective narrative about its people and history—defining social place and hierarchy through a matrix of selective memory, willed forgetting, and racial determinism. With the defeat of the Confederacy, wrote Robert Penn Warren, “the Solid South was born”—a “City of the Soul” rendered guiltless by the forces of history. “By the Great Alibi,” he continues, “the South explains, condones and transmutes everything… any common lyncher becomes a defender of the Southern tradition…. pellagra, hookworm, and illiteracy are all explained, or explained away…. By the Great Alibi the Southerner makes his Big Medicine. He turns defeat into victory, defects into virtues. . . . And the most painful and costly consequences of the Great Alibi are found, of course, in connection with race.”

Because it was a society based on the myths of innate racial difference, a hierarchy based on notions of supremacy—white superiority and its conjoined twin black inferiority—the language used to articulate that thinking was rooted in the unique experience of white southerners. The role of metaphor is not only to describe our experience of reality; metaphor also shapes how we perceive reality. Thus, in the century following the war, the South—in the white mind of the South—became deeply entrenched in the idea of a noble and romantic past. It was moonlight and magnolias, chivalry and paternalism. The blacks living within her borders, when they were good, were “children” to be guided, looked after, protected from their own folly, “mules” of the earth, “darkies” with the “light of service” in their hearts. When they stepped out of line, they were “bad niggers” from whom white women—carriers of the pure bloodline—needed to be protected; they were animals to be husbanded into a prison system modeled on the plantation system—or worse, strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees. On the monumental landscape, in textbooks, they were unstoried but for the stories told about them. In my twelfth grade history book they were “singing and happy in the quarters,” “better off under a master’s care.” According to my teacher, they were “passive recipients of white benevolence” who’d “never fought for their own freedom”—even as nearly two hundred thousand fought in the Civil War.

In the century following the war, the South—in the white mind of the South—became deeply entrenched in the idea of a noble and romantic past. It was moonlight and magnolias, chivalry and paternalism.

And when they seemed exceptional in the mind of the South, they were magical: You’re smart for a black girl, pretty for a black girl, articulate—not like the rest of them . . .

Through the misuses of history, the creation of “hallowed” falsehoods, as historian John Hope Franklin pointed out, the white South found “the intellectual justification for its determination not to yield on many important points, especially in its treatment of the Negro.”

“Geography is fate,” wrote Ralph Ellison, adapting Heraclitus’s axiom to the idea of place rather than character. In Georgia, a hulk of bald granite called Stone Mountain serves as a lasting metaphor for the white mind of the South. The nation’s largest monument to the Confederacy, it rises out of the ground like the head of a submerged giant—the nostalgic dream of southern heroism and gallantry emblazoned on its brow: in bas-relief, the enormous figures of Stonewall Jackson, Robert E. Lee, and Jefferson Davis. I grew up near the base of the mountain, in its shadow, dividing my time between Georgia and Mississippi. In both geographies, public monuments and the associated rituals of memory and memorialization provided the nascent framework for my interest in the intersections and contentions between personal and public memory, the creation of cultural memory and collective history with its absences, its erasures and omissions, and notions of voice and authority in the making and documenting. “Those who can create the dominant historical narrative,” wrote historian David Blight, “will achieve political and cultural power.” I ask: what’s been left out of the historical record of my South and my nation? What is the danger in not knowing? How does historical amnesia shape our perception of the world, our interactions with others? How am I complicit in wielding the tools of silence and oblivion?

In my collection Native Guard, these questions guided my research—the scholarly investigation that led to the act of discovery that poetry engenders. As poet Mark Doty wrote: “Our metaphors go on ahead of us.” I began researching and writing Native Guard with an interest in exploring the history of black Civil War soldiers on the Mississippi Gulf Coast to whom no monuments had been erected. As historian Eric Foner points out, of the hundreds of Civil War monuments North and South, only a handful make any mention of black participation in the war. In my hometown, and even in the National Military Park in Vicksburg, they had been erased from the monumental landscape and from our cultural memory as well. At the spine of the collection is the title poem, a sonnet sequence that illuminates the life of an imagined soldier, a member of the second regiment stationed off the coast of Gulfport at the fort on Ship Island. I’d grown up going out to that island every year on the 4th of July, taking the tour of the fort, and never once learning from the park ranger anything about the black Union soldiers who’d been stationed there, guarding Confederate prisoners. That certain facts are often left out of local historical narratives and (perhaps until most recently) were likely to be given only a small part in larger histories, suggests something about the way Americans remember the Civil War and its aftermath, how we construct public memory with its omissions and embellishments.

The South of my childhood was a landscape overwritten with a dominant narrative, burying almost completely any others. But for the streets named for Martin Luther King Jr., the monuments were mostly to Confederate soldiers, staunch segregationists, governors and klansmen, often one in the same. The textbooks I read glorified the institution of slavery, devoted little time to Reconstruction and the horrors inflicted upon African Americans in the aftermath of Reconstruction, the Jim Crow era, and the Civil Rights Movement. I felt both erased and then penciled in again as the descendant of a caricature—the raggedy black minstrel who’d given his name to the whole race. I felt profoundly E. O. Wilson’s words: Homo Sapiens is the only species to suffer psychological exile. I was an outsider in my own homeland: my Mississippi—with its myriad contradictions—home to “the most southern place on earth,” so named for its brutal history of injustice, racial oppression, violence, and lynching; my Mississippi, birthplace of the blues, a literary tradition rich and fertile as Delta soil, one of the poorest states in the nation; my Mississippi, with its terrible beauty—to borrow from William Butler Yeats—borne on the backs of slaves and through the resistance of their descendants, the astonishing resilience of African Americans in the face of Jim Crow: a terrible beauty born in spite of it. As in W. H. Auden’s memorial to Yeats—Mad Ireland hurt you into poetry—Mississippi inflicted my first wound.

I felt both erased and then penciled in again as the descendant of a caricature—the raggedy black minstrel who’d given his name to the whole race.

Writing Native Guard was a way to talk back to authoritative histories, to confront the misapprehensions therein, to restore what had been erased. According to historian C. Vann Woodward, during the last two decades of the nineteenth century and the first two of the twentieth, by commissioning the writing of textbooks, the erecting of monuments, the naming of roads and bridges, it was “white ladies… who bore primary responsibility for the myths glorifying the old order, the Lost Cause, and white supremacy.” Woodward was referring, specifically, to the United Daughters of the Confederacy, the Daughters of the American Revolution, Daughters of Pilgrims, and Daughters of Colonial Governors; they were considered “guardians of the past.” “Non-daughters,” he writes, “were excluded.”

In southern poetry, this kind of public memory-making is rooted in the Fugitive-Agrarian stance that, according to the editors of the anthology of twentieth-century southern poetry Invited Guest, “supplied the central discursive structures from which African Americans and women would compose in antithetical fashion, that is, a thesis giving rise to an antithesis.” I see my work, however, not merely as antithesis, but as synthesis, and the Agrarian sidestepping of race as an unfortunate, though integral omission. As in a photograph in which someone has been cut out—the empty space, a hole letting the light shine through—the absence becomes as palpable as the former presence. My work to fill in the blanks, the absences and omissions, is not, then, antithetical; the narratives I seek to restore have been there all along. Thus, in positioning myself as a native daughter, a native guardian of Mississippi’s past, I sought to write myself into the history of my symbolic geography on my own terms and to challenge certain notions about the canon of southern literature.

In a larger sense, the title Native Guard held for me not only literal but also figurative possibilities, and in writing it I discovered what lay beneath the surface of my scholarly inquiry. “We make of the quarrel with others, rhetoric,” wrote Yeats, “but of the quarrel with ourselves, poetry.” I had begun with the quarrel I had with my state, region, and nation over historical amnesia—willed forgetting of the role of African American soldiers in the Civil War and selective remembering about the aftermath. By the time I was finished I had discovered the argument with myself: all those years after my mother’s death I had never put a monument on her grave. She lay in the ground unmarked, not properly memorialized by the one whose native duty it was to remember. Like those black soldiers, she had been erased from the monumental landscape. My metaphor had gone on ahead of me; the work of research is what allowed me to catch up to it.

Though in my work I move frequently between free and fixed forms, Native Guard is my most formal collection. In it, traditional forms become not only a container for grief but also—as with the repetition of the blues—a way to transform it. I see also in the attempt to re-inscribe narratives that have been erased the need for repetition. It is necessary not only to say a thing, but to say it again, thus I make the most use of received forms that are rooted in repetition and refrain: the crown of sonnets, the villanelle, pantoum, ghazal, palindrome. These forms, too, are monumental.

Audre Lorde wrote, “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” I know of course that she was referring to the myriad tools of oppression, from laws to custom, all rooted in the thinking—powerfully metaphorical—that shapes our perception of others, the social reality we create in which to live. But when I read her words I can’t help but think of the received forms of poetry I learned in school—sonnets, for example—and how I have turned to such forms to contain the subject matter necessary to challenge the master narrative. In that way, I believe the traditional forms—the masters’ tools—can help in the dismantling of a monolithic narrative based on racial hierarchy, willed amnesia, and selective remembering.

3. You Are Not Safe in Science

And by science I mean, in the largest sense, knowledge—philosophy, the science of thought. This is where the danger of which Frost warned is for me most piercing. Thus far I have been speaking of the mind of the white South—the received knowledge of the region, seemingly discrete, informed by the inhabitants’ perceptions of their lived experience, and yet not: a knowledge whose roots stretch back centuries and across space as well as time. Consider again the mule, the mulatto, what Immanuel Kant—in his racial classification—referred to as Mittelschlag. Indeed, it is through the knowledge production of Enlightenment scientists such as Linneaus and philosophers such as Kant and Hume that we can chart the codification of racial difference and hierarchy, the roots of nineteenth-century scientific racism, and the bedrock of ongoing, deeply ingrained, and often unexamined contemporary notions of racial difference—received knowledge becomes synonymous with truth. Thus, in my collection Thrall, I was interested in examining empire and the intersections between the sciences and production of ideas of racial difference across the Age of Reason.

We can chart the codification of racial difference and hierarchy, the roots of nineteenth-century scientific racism, and the bedrock of ongoing, deeply ingrained, and often unexamined contemporary notions of racial difference—received knowledge becomes synonymous with truth.

In the introduction to his fifteenth-century book of Castilian grammar, Antonio de Nebrija wrote, “Language has always been the perfect instrument of empire.” I found my way to the title Thrall by considering the word native in its relationship to empire and colonization. The etymology is rooted in slavery: the word’s primary definition, someone born in bondage, a thrall. My exploration of the language of empire focused on the lexicon used to define mixed-blood people and metaphors to maintain ideas of innate difference and inferiority: for example, what was codified as the taint of blackness—the eighteenth-century mythology that, even if hidden from plain view, not evident in skin color, it could be identified by the presence of a dark spot on the genitals of anyone with African blood.

The sequence of poems that is the foundation of the collection takes as its starting point the eighteenth-century Mexican Casta paintings that depict the various mixed-blood unions taking place in the colony, the children of those unions, and their social status and perceived place in a society growing increasingly racialized. In colonial Mexico, the designation of Casta relegated those with mixed blood to various levels of the social strata, beneath the pureblood Spaniards. The Casta paintings, in their depiction of these mixed-blood offspring of natives and slaves and conquerors, present a captivating taxonomy as well—words on each canvas that name the racial makeup of the figures. The paintings were done in series of sixteen, beginning with the white Spaniard father. The ideas suggested by the paintings, echoing the knowledge production of the period, have stayed with us, embedded as latent cultural beliefs: for example, that through a few generations of mixing, indigenous blood could be purified to whiteness, but that the taint of African blood, as with the one-drop rule, is irreversible. In colonial Mexico the resulting taxonomies included mulatto-returning-backwards, hold-yourself-in-mid-air, and I-don’t-understand-you.

Whereas paintings in the earlier part of the century are relatively neutral in their representations of the various types, the images of the latter part are evidence of a troubling history of thought about the character of the people represented. For example, when a black woman appeared as part of an interracial union in the late century, she was frequently shown lunging to stab or strike the white father as their mulatto child tries to restrain her—scenes, according to art historian Ilona Katzew, that meant to suggest “domestic degeneracy,” the depravity of black women—that they were intrinsically violent. “The message is clear,” she writes. “Certain mixtures—particularly those of Spaniards or Indians with blacks—can only lead to debased sentiments, immoral proclivities, and extreme susceptibility to an uncivilized state. The incorporation of this type of scene in a number of casta sets serves to highlight the positive traits associated with mixtures that excluded blacks, which bore the promise of a return to a pure racial pole.” Such images undergirded attempts at social control as they were intended to relegate people to their designated places in the supposed natural order of things. The paintings seem to suggest a darker, predetermined interpretation of Heraclitus’s axiom “Character is fate,” as if it were something innate and immutable.

The legacy of such knowledge production is deeply ingrained, manifest in contemporary culture and even in the intimate relations within families, as with my white father. To be a historical being is to be caught up in the web of history, and I see the necessity of an engagement with history as way to look outward, beyond the inward-turning lens of self-reflection to contemplate one’s place in the world and to illuminate aspects of personal experience through a much larger lens of shared experience across time and space. Ekphrasis is a useful tool in this endeavor as I look to the images in art not only to provide insight into the historical moment but also to provide a means by which to unlock the psychological landscapes that shape the way I see figures, objects, and their juxtapositions in the contemporary moment.

The legacy of such knowledge production is deeply ingrained, manifest in contemporary culture and even in the intimate relations within families, as with my white father.

“Poetry,” wrote Wallace Stevens, “is the scholar’s art.” Because a poem is in itself theoretical, pursuing insight into the nature of things, advancing ideas about language and meaning, as well as being in conversation with other discourses and forms of art, I include here a couple of poems that articulate my thinking, illustrating the intersections between public and personal history.

Taxonomy

……After a series of casta paintings

……by Juan Rodríguez Juárez, c. 1715

1. DE ESPAÑOL Y DE INDIA

…PRODUCE MESTISO

The canvas is a leaden sky

…….behind them, heavy

with words, gold letters inscribing

…….an equation of blood—

this plus this equals this—as if

…….a contract with nature, or

a museum label,

…….ethnographic, precise. See

how the father’s hand, beneath

…….its crown of lace,

curls around his daughter’s head;

…….she’s nearly fair

as he is—calidad. See it

…….in the brooch at her collar,

the lace framing her face.

…….An infant, she is borne

over the servant’s left shoulder,

…….bound to him

by a sling, the plain blue cloth

…….knotted at his throat.

If the father, his hand

…….on her skull, divines—

as the physiognomist does—

…….the mysteries

of her character, discursive,

…….legible on her light flesh,

in the soft curl of her hair,

…….we cannot know it: so gentle

the eye he turns toward her.

…….The mother, glancing

sideways toward him—

…….the scarf on her head

white as his face,

…….his powdered wig—gestures

with one hand a shape

…….like the letter C. See,

she seems to say,

…….what we have made.

The servant, still a child, cranes

…….his neck, turns his face

up toward all of them. He is dark

…….as history, origin of the word

native: the weight of blood,

…….a pale mistress on his back,

heavier every year.

2. DE ESPAÑOL Y NEGRA PRODUCE MULATO

Still, the centuries have not dulled

the sullenness of the child’s expression.

If there is light inside him, it does not shine

through the paint that holds his face

in profile—his domed forehead, eyes

nearly closed beneath a heavy brow.

Though inside, the boy’s father stands

in his cloak and hat. It’s as if he’s just come in,

or that he’s leaving. We see him

transient, rolling a cigarette, myopic—

his eyelids drawn against the child

passing before him. At the stove,

the boy’s mother contorts, watchful,

her neck twisting on its spine, red beads

yoked at her throat like a necklace of blood,

her face so black she nearly disappears

into the canvas, the dark wall upon which

we see the words that name them.

What should we make of any of this?

Remove the words above their heads,

put something else in place of the child—

a table, perhaps, upon which the man might set

his hat, or a dog upon which to bestow

the blessing of his touch—and the story

changes. The boy is a palimpsest of paint—

layers of color, history rendering him

that precise shade of in-between.

Before this he was nothing: blank

canvas—before image or word, before

a last brush stroke fixed him in his place.

3. DE ESPAÑOL Y MESTIZA PRODUCE CASTIZA

How not to see

…….in this gesture

the mind

…….of the colony?

In the mother’s arms,

…….the child, hinged

at her womb—

…….dark cradle

of mixed blood

…….(call it Mexico)—

turns toward the father,

…….reaching to him

as if back to Spain,

…….to the promise of blood

alchemy—three easy steps

…….to purity:

from a Spaniard and an Indian,

…….a mestizo;

from a mestizo and a Spaniard,

…….a castizo;

from a castizo and a Spaniard,

…….a Spaniard.

We see her here—

…….one generation away—

nearly slipping

…….her mother’s careful grip.

4. THE BOOK OF CASTAS

Call it the catalog

…….of mixed bloods, or

…….the book of naught:

……….not Spaniard, not white, but

mulatto-returning-backwards (or

…….hold-yourself-in-midair) and

…….the morisca, the lobo, the chino,

……….sambo, albino, and

the no-te-entiendo—the

…….I don’t understand you.

…….Guidebook to the colony,

……….record of each crossed birth,

it is the typology of taint,

…….of stain: blemish: sullying spot:

…….that which can be purified,

…….that which cannot—Canaan’s

black fate. How like a dirty joke

…….it seems: what do you call

…….that space between

……….the dark geographies of sex?

Call it the taint—as in

…….T’aint one and t’aint the other—

…….illicit and yet naming still

…….what is between. Between

her parents, the child,

…….mulatto-returning-backwards,

…….cannot slip their hold,

……….the triptych their bodies make

in paint, in blood: her name

…….written down in the Book

…….of Castas—all her kind

……….in thrall to a word.

Enlightenment

In the portrait of Jefferson that hangs

…….at Monticello, he is rendered two-toned:

his forehead white with illumination—

a lit bulb—the rest of his face in shadow,

…….darkened as if the artist meant to contrast

his bright knowledge, its dark subtext.

By 1805, when Jefferson sat for the portrait,

…….he was already linked to an affair

with his slave. Against a backdrop, blue

and ethereal, a wash of paint that seems

…….to hold him in relief, Jefferson gazes out

across the centuries, his lips fixed as if

he’s just uttered some final word.

…….The first time I saw the painting, I listened

as my father explained the contradictions:

how Jefferson hated slavery, though—out

…….of necessity, my father said—had to own

slaves; that his moral philosophy meant

he could not have fathered those children:

…….would have been impossible, my father said.

For years we debated the distance between

word and deed. I’d follow my father from book

…….to book, gathering citations, listen

as he named—like a field guide to Virginia—

each flower and tree and bird as if to prove

…….a man’s pursuit of knowledge is greater

than his shortcomings, the limits of his vision.

I did not know then the subtext

…….of our story, that my father could imagine

Jefferson’s words made flesh in my flesh—

the improvement of the blacks in body

…….and mind, in the first instance of their mixture

with the whites—or that my father could believe

he’d made me better. When I think of this now,

…….I see how the past holds us captive,

its beautiful ruin etched on the mind’s eye:

my young father, a rough outline of the old man

…….he’s become, needing to show me

the better measure of his heart, an equation

writ large at Monticello. That was years ago.

…….Now, we take in how much has changed:

talk of Sally Hemings, someone asking,

How white was she?—parsing the fractions

…….as if to name what made her worthy

of Jefferson’s attentions: a near-white,

quadroon mistress, not a plain black slave.

…….Imagine stepping back into the past,

our guide tells us then—and I can’t resist

whispering to my father: This is where

…….we split up. I’ll head around to the back.

When he laughs, I know he’s grateful

I’ve made a joke of it, this history

…….that links us—white father, black daughter—

even as it renders us other to each other.

4. Calling

Some selected image of the past is always being delivered to our senses.

……—Adrienne Rich

The wound is the place where the light enters you.

……—Rumi

Over the years, my mind has turned again and again to that earliest memory of my near drowning, the image of my mother above me, arms outstretched, a corona of light around her face. Did I know then that it reflected an iconic image of sainthood? The mind works such that we see and perceive new things always through the lens of what we have already seen. What came first then, the vision of my mother as I was sinking deeper into the pool, or religious paintings and altarpieces depicting the saints in much the same way? What matters is the transformative power of metaphor and the stories we tell ourselves about the arc and meaning of our lives. Since that day decades ago, the imagery of the memory has remained the same, I think, because I have rehearsed it, telling the story of my near drowning again and again. What has changed is how I’ve understood what I saw, how I’ve come to interpret the metaphors inherent in my way of recalling the events. Scientists tell us there are different ways that the brain records and stores memory, that trauma is inscribed differently than other types of events.

To survive trauma, one must be able to tell a story about it. If the story I began to tell myself after the seemingly small trauma of almost drowning was that my mother had been there, that I was in no real danger, that she was somehow ethereal, a light-ringed saint to whom I might send up my prayers for salvation, the story evolved over the years to create a narrative of self that could contain yet another trauma and give it meaning. Near the end of my freshman year in college my mother was murdered—gunned down in a parking lot by her then ex-husband, a troubled Vietnam veteran with a history of mental illness, a man who had been my stepfather for ten difficult years.

Not long after her death I dreamt of her, and it has taken me nearly forty years to understand the connection the images were making in my subconscious. In the dream, I knew that she was dead and it seemed as if I had journeyed somewhere to meet her. We were walking side by side and only once did she speak, turning to ask me a final question: Do you know what it means to have a wound that never heals?

Articulation

After Miguel Cabrera’s portrait of Saint Gertrude, 1763

In the legend, Saint Gertrude is called to write

after seeing, in a vision, the sacred heart of Christ.

Cabrera paints her among the instruments

of her faith: quill, inkwell, an open book,

rings on her fingers like Christ’s many wounds—

the heart emblazoned on her chest, the holy

infant nestled there as if sunk deep in a wound.

Against the dark backdrop, her face is a wafer

of light. How not to see, in the saint’s image,

my mother’s last portrait: the dark backdrop,

her dress black as a habit, the bright edge

of her afro ringing her face with light? And how

not to recall her many wounds: ring finger

shattered, her ex-husband’s bullet finding

her temple, lodging where her last thought lodged?

Three weeks gone, my mother came to me

in a dream, her body whole again but for

one perfect wound, the singular articulation

of all of them: a hole, center of her forehead,

the size of a wafer—light pouring from it.

How, then, could I not answer her life

with mine, she who saved me with hers?

And how could I not—bathed in the light

of her wound—find my calling there?

We know of course that dreams are metaphorical. And in the moment of waking from it, my mother’s voice ringing in my head, I was transformed. The world as I knew it and myself in it were not the same. I had acknowledged the undeniable presence of my deepest wound, and something of the past was delivering to me again a familiar scene but in the negative—a reversal of light and dark that transformed my mother’s face into pure light ringed in darkness. The light all-consuming and piercing.

Over the years, as I applied the dream again and again to the ongoing narrative of my life, I began to see it as a bookend to my earliest memory—as if indeed my earliest memory had provided the discursive framework of the dream. Being pulled from the water into my mother’s arms was akin to a baptism. I had witnessed something strange, not unlike the visions reported by the faithful which set them on a path of devotion, of meaningfulness and purpose: my mother, through the wavering lens of water, seemed distant and not fully embodied—an apparition, the dead woman she was to become, but with the light surrounding her as if she had already undergone her hagiography.

In the narrative of my life, which is of course the look backward rather than forward into the unknown and unstoried future, I emerged from the pool as from a baptismal font—changed, reborn—as if I had been shown what would be my calling even then. Years later, the dream would answer that early vision, would provide me the abiding metaphor by which I have come to live. My writing life began not long after that, and I have been trying to answer my mother’s last question to me—Do you know what it means to have a wound that never heals?—ever since.

This essay appears in the Documentary Moment Issue (vol. 26, no. 1: Spring 2020). It was originally delivered as the first annual John Hope Franklin Lecture for the Franklin Humanities Institute at Duke University on March 21, 2018. Portions have been adapted from Memorial Drive: A Daughter’s Memoir, forthcoming July 2020 from Ecco (available for pre-order now).

NATASHA TRETHEWEY served two terms as the nineteenth Poet Laureate of the United States (2012–2014). She is the author of five collections of poetry, Domestic Work (2000), Bellocq’s Ophelia (2002), Native Guard (2006)—for which she was awarded the 2007 Pulitzer Prize—Thrall (2012), and Monument: Poems New and Selected (2018). In 2010 she published a book of nonfiction, Beyond Katrina: A Meditation on the Mississippi Gulf Coast. She is a chancellor of the Academy of American Poets, and recipient of fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Guggenheim Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation, the Beinecke Library at Yale, the Academy of American Poets, and the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard. A fellow of both the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Letters, Trethewey received the Heinz Award for Arts and Humanities in 2017. She is currently Board of Trustees Professor of English at Northwestern University. Her memoir, Memorial Drive, will be published in July 2020.