Back when John Updike didn’t get it, Shannon Ravenel did. From her early days in New York publishing, to co-founding Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill and editing the essential New Stories from the South series for two decades, Ravenel has been at the fore of shaping and sharing southern literature. We recently sat down with the editor and publisher (extraordinaire) for our Loose Leaf series. In addition to our video interview with Ravenel, we are sharing an excerpt from our conversation below.

Interview Excerpt

Shannon Ravenel for Loose Leaf

When I was in college, I found out that my major professor was also from Charleston, where I grew up. That was Louis Rubin. He kindly, subtly, pointed me towards publishing. Not writing. I was in a lot of writing workshops and he told me I would make a better editor than writer (laughs), which was great advice. So I went to New York, and then I went to Boston the following year. In 1961, I joined the editorial department of Houghton Mifflin as a secretary, which is what happened in those days—you were not an editorial assistant, you were a secretary. I took shorthand, and I quickly figured out ways of finding things that were interesting and showing them to the editors.

So without really realizing it, I was already beginning to move towards southern literature.

The first book that they actually allowed me to acquire was a first novel by a young black man [Robert Boles]. Looking back, I realize that the reason it appealed to me was because he was black, and because his family was Mississippian, and because he was writing about the difficulty of being black. So without really realizing it, I was already beginning to move towards southern literature. I didn’t really know it. And while I was at Houghton Mifflin I acquired also Pat Conroy, who was very southern and lived near me in Charleston. And I don’t think I had actually ever thought that that’s what I was doing, but it just kept happening that the books I felt sort of serious about and enthusiastic about and pushed very hard [were southern], including Robert Boles’s second book. The first one sold miserably, the second one sold even more miserably, but I pushed very hard because I thought his voice was important.

I was in my twenties and I married someone who was moving all around with his science career and I had to leave Houghton Mifflin. And very, very, very fortunately for me, Martha Foley, the lady who had edited the Best American Short Stories for, I don’t know, thirty years, retired. At that point HMCo decided to change the way that book was dealt with and to give it to a series editor who would read all the stories [and] narrow down 120 of them each year to hand to the guest editor. So that was me, I was the series editor. I made $1,500 dollars a year, and each year I read close to 2,000 stories in all kinds of magazines from all over the country and Canada . . . As I did, I soon realized that the guest editors tended not to be southern. And that the number of stories, the percentage of stories that I handed them that were southern, that they selected to be published in each Best American—they chose twenty, and the other one hundred of my list got listed in the back—the percentage was quite low. Richard Ford was the first and only southern guest editor, and he chose a single southern short story his year.

The year that made a big difference to me was 1984, which was one year after Louis and I had—it was his brainchild, he just asked me to join him—started Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. I read all the stories in 1983, chose 120 of them to give to the guest editor, who was John Updike, and he chose his twenty. And he said, “There is one story in this list that I do not want represented in the book. I do not want it on the list, it is a terrible short story and it should not appear.” It was by Lewis Nordan, who had published two books previously that had done nothing. I had not read his books, but I found this story that I gave to John Updike in a literary magazine and it blew me away. (Lewis Nordan later wrote Wolf Whistle, which was about Emmett Till.) Anyway, I was so—I won’t say what I was—I was “very annoyed.” And a year later when Louis and I were talking about what we could do to add to Algonquin’s push for literature, he said, “What about an annual book of the best new stories from the South?” And I thought, “And the first one’s going to be one by Lewis Nordan.” I think that was the first time I really understood that southern literature needed some pushing and that it wasn’t in the mainstream . . . So we started New Stories from the South and I edited that for twenty years.

It was something that Updike simply didn’t get. He just didn’t understand what the humor was, he didn’t know where it came from, and he couldn’t relate it to anything. I think nobody’s ever been more of a Yankee than John Updike.

I think [Updike] just didn’t get it . . . [S]outhern literature comes from a part of the country that not everybody’s grown up in. Lewis Nordan—we called him Buddy—Buddy was an innovator, he had a style that was completely and utterly original, and very strange, and very funny. And I think basically . . . it wasn’t an Emmett Till story. It was called “Sugar Among the Freaks” [and] . . . it was over the top in Nordan’s funny, strange way, and it was something that Updike simply didn’t get. He just didn’t understand what the humor was, he didn’t know where it came from, and he couldn’t relate it to anything. I think nobody’s ever been more of a Yankee than John Updike (laughs), and it was just a matter of not understanding it. I shouldn’t have been mad, I should’ve been just, “Oh, I see, he doesn’t get it, that’s not his fault.” But to tell me that I couldn’t list it in the back, well . . . so there were only ninety-nine stories listed in that one . . . As far as I know—I don’t believe John Updike even ever traveled to the South, and that was true of a lot of people, I think.

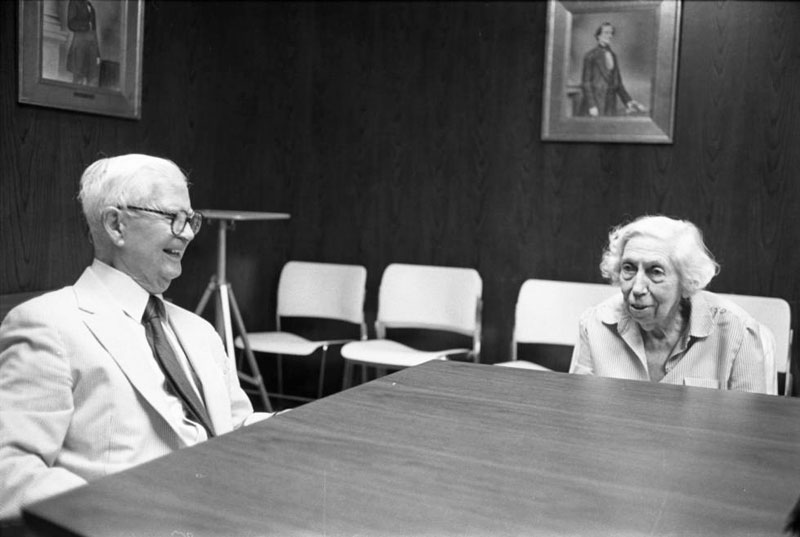

Cleanth Brooks and Eudora Welty. Photo by William R. Ferris. Courtesy of the William R. Ferris Collection in Wilson Library’s Southern Folklife Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Louis Rubin decided, along with Cleanth Brooks, and Eudora Welty, and the other people among those who started the Fellowship of Southern Writers [in 1987], that southern literature was just not paid enough attention. Its goal was always to bring attention particularly to new southern writers. Louis worked all the time. He stayed up all night as far as I could tell. I mean, in addition to founding Algonquin Books, he founded the Fellowship of Southern Writers, and he taught full-time—you know, he was doing everything.

He wrote me on New Year’s Day 1982 and he said, “I’ve been thinking that what is missing from the world of books is a house that is outside of New York, away from New York, and in another part of the country. I don’t mean to start a southern publishing company; I simply mean to start a publishing company that is not in New York.” I guess he had the feeling that if you were in New York, you were too apt to think about money, and Louis did not think much about money. In fact, we went bankrupt immediately, almost immediately, but he said, “I don’t mean to publish only literature from the South, I mean to publish the best literature we can find.” I think he knew that it was probably not smart to say he just wanted to have a southern company, and that we wouldn’t get nearly the attention of agents and so forth if we were only looking for southern, which was very smart. However, the only people at first who’d heard of us were people around here like Clyde [Edgerton] and Jill [McCorkle], who was one of his students. So the first books that we did publish that made any kind of splash at all were southern and we soon became known as a southern publishing house. But we never published just southern books.

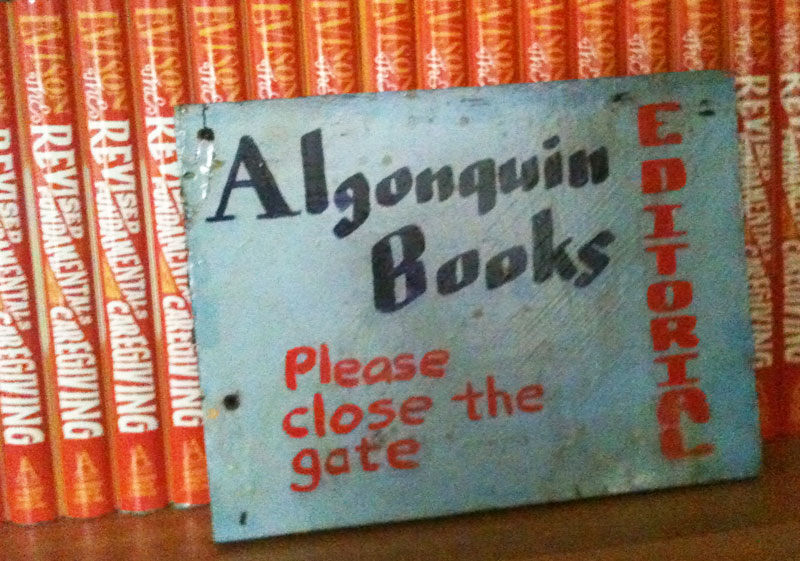

I was living in St. Louis with my scientist husband and kids and editing Best American Short Stories and Louis was down here [in Chapel Hill]. I wrote him back the next day and said, “Yes, yes, I don’t know what to say. I don’t have much money but my aunt just died and I could scrape up a little bit.” We actually sold stock (laughs) and . . . we scraped together enough money to start and we were established. I was in Saint Louis, he was here. Mimi Fountain, who was another former student of his at Hollins, joined as a “gal Friday” and soon became the publicity director. All of this happened in the shed behind Louis’s house on Gimghoul Street. And we have a wonderful little gate sign at the office now that Robert Rubin painted [that] says, “Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. Please close gate against dog.” (Laughs). It’s adorable. I hope somebody puts it in a museum someday.

In 1983, Algonquin Books set up shop in a woodshed behind co-founder Louis Rubin’s Chapel Hill, N.C., home. Photo courtesy of Algonquin Books.

So we started the first list . . . and it was a struggle for money. We had to find money, money was a big deal. We paid very small advances and people were willing to go along with that, but you know, it was getting the books printed and shipped and it was the marketing . . . [W]e kept running out of money. So Louis and I decided that we had to put the company up for sale. My husband’s Yale roommate, Peter Workman, had founded Workman Publishing in 1968, so I would call Peter Workman and I say “OK, here’s where we are.” Peter was an English major, but his company published nothing but “how-to” books and cookbooks and cute little kids’ books. He was very successful. Very successful. So I would call him up and say, “Look, Peter, we have a thousand dollars extra. What should we do with this?”

And he would say, “Take out a full page ad in Publisher’s Weekly.” All along I would call him whenever we needed advice and he would give it gladly and he got kind of interested. We had an agent friend Liz Darhansoff in New York and she let it be known amongst the publishers in New York that we were looking to be bought. And, long story short, Random House decided they wanted to buy us.

They didn’t come down and look, which was interesting; they brought Louis and me to New York to have a conference. On the plane, Louis was wearing a white linen jacket, and his pen—Louis was a bit of a slob—his pen exploded in his jacket pocket. So we got to Random House and he had this huge navy blue stain (laughs). We were taken to an office where everybody had gold cuff links and we were served, you know, little things to nibble on and coffee, and this proposed purchase was discussed. They laid out the proposition and how it would work and blah, blah, blah, and we said, “Thanks, you know, this is great and we’d like to go back and think about it very, very carefully, and we’ll be in touch in a week.” When we got outside I said, “Louis, let’s call Peter just because we’re here and our plane doesn’t leave for awhile. Let’s call Peter and see what he thinks.”

And Peter said, “Oh, it’s gotten that far?”

And I said, “Yeah, and we have an offer, and we’d love to have you look at it if you have a minute.”

He said, “Well why don’t you come on down.” So we went on down and we had some lunch at McDonald’s—very different from Random House. And he said, “I think it would be better if you came to us.” He had never mentioned that before. And Louis and I said, “Oh my gosh!”

He said, “The reason is, I don’t do your kind of stuff. And therefore I will not be tempted to interfere.”

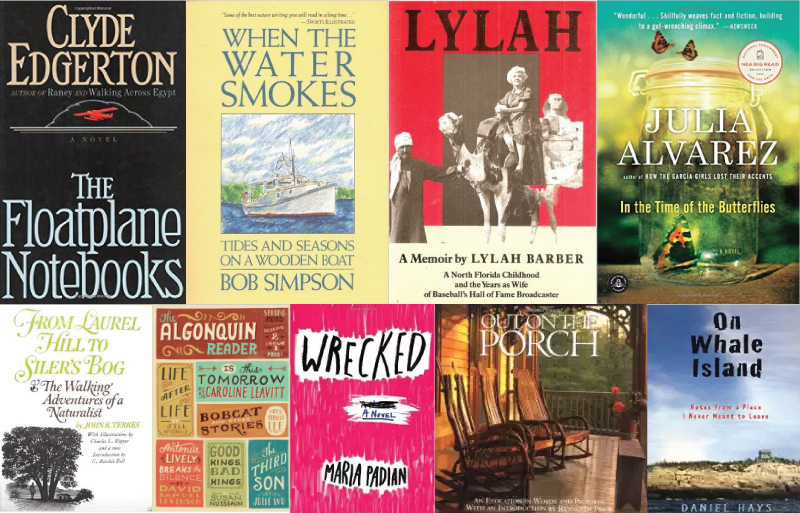

A selection of Algonquin books published over the last thirty-three years.

Louis said, “You’re right!” (Laughs). So we became a part of Workman Publishing. It worked very well, except that they did interfere with the nonfiction, which Louis was particularly involved in. And he got mad and quit. He quit in ’91, I think, which was very sad.

Southern literature has picked up in people’s minds . . . the U.S. reading public has much less resistance to new southern work than it once did.

But he was Louis Rubin and he was, I don’t know, 70-something and he wanted me to come with him and start again. It’s one of the tragedies that I couldn’t afford it. At this point I had two kids heading for college and a salary (laughs). So he did not start another one. But never quit writing. I think he published 55 books of his own. And gradually got over the split, thank goodness. He was a father figure to me, certainly a very strong mentor. But [it’s] amazing that he dreamt up Algonquin Books and saw it through. And kept it going.

I would just say that I think that because of Louis Rubin and because of the books that Algonquin published, southern literature has picked up in people’s minds. I think it’s more respected and more known. And that is very good. Now, you see a lot of southern writers becoming much more nationally known. Lee Smith is one I think who really took it a long way. And she’s about as southern as you get. Writers like Lewis Nordan, they are still trickier to publish, they are still harder to market. That’s true of many literary writers, not just southern ones. But the U.S. reading public has much less resistance to new southern work than it once did.