Music is baked into Southern Cultures. We have run no less than eight special issues devoted to musics of the South. And music scholarship has regularly peppered our pages in between, from our beginnings in the mid-1990s to the present. To be sure, music is good to think with. Like all expressive culture, it provides a window into the values, conflicts ,and aesthetic preferences of its audiences. But music is a culture all its own, too, replete with social standards, tools of the trade, specific language, and solidarity among practitioners. The following essays demonstrate the way southern music helps us understand the diverse communities of the South, including communities of musicians themselves. Consistent themes for students to explore here include: race, identity, authenticity, and genre.

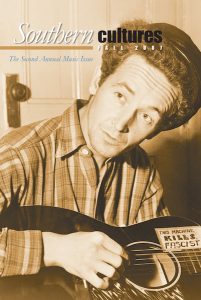

The Color of Music: Social Boundaries and Stereotypes in Southwest Louisiana French Music

Sara Le Menestrel, Vol. 13, No. 3 (Fall 2007)

What people recognize today as Louisiana French music falls into two main categories: Cajun, played primarily by white musicians, and zydeco, played mostly by black musicians. Le Menestrel’s essay unpacks the history of “la musique francaise,” the general term used before 1960 for music played by both Cajun and Creole musicians in the small towns and rural house parties and dance halls in Southwest Louisiana. While overlapping in style and form, the bands, audiences, and settings for the performance and consumption of this music were segregated along racial lines. Le Menestrel points to the ways that French music followed popular trends during the twentieth century, incorporating ragtime, western swing, and popular songs, often translated from English into French, and rhythm and blues. At the same time, a jazz scene with ties to New Orleans thrived among Creoles in the region also. After WWII, zydeco emerged as a distinctive Creole musical genre. Today, musicians and cultural commentators have made efforts to celebrate the common threads between Cajun and zydeco music. Beau Soleil, a popular Cajun band, has several zydeco tunes in its repertoire. And Geno Delafose, a beloved zydeco musician, plays Cajun songs and collaborates with Cajun musicians. Still, Le Menestrel argues, the musical distinctions persist and reflect the “complexity of social relations among Cajuns and Creoles” and the racial and social divides inherent in the larger society (104). This is a great article for introducing students to Cajun and zydeco musical genres and for initiating conversations about music and identities. Article >

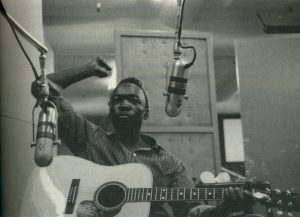

“Where is the Love?” Racial Violence, Racial Healing and Blues Communities

Adam Gussow, Vol. 12, No. 4 (Winter 2006)

In this essay, Gussow focuses on how blues music names the wounding inflicted by white supremacy on African Americans in the Deep South. Mississippi is the birthplace not only of blues music, Gussow argues, but also of blues feeling, “a whole complex of emotions and attitudes engendered in its African American residents” (36). He looks at the complex relationship between blues as counter culture and at its evolution as a form of cultural tourism in Mississippi. Gussow acknowledges that “blues tourism” can be seen as one more way “white capital extracts profit from black artistry without truly sharing in the wealth” (36). But he also points to instances of how African Americans are helping generate and are capitalizing on this wave of cultural tourism. Gussow is careful to concede that contemporary local blues scenes can be sites fraught with essentializing when white audiences and participants come looking for authentic black experiences and expressions. But he argues that such scenes can also be places of redemption, since they attract loving attention to the blues. And here, he draws on bell hooks, who, he contends, holds the “master key” to the blues: “…to have the blues is to be wounded in the place where we would know—or have known—love” (41). This essay provides an excellent way to open conversations about the blues as musical genre, and particularly about the meaning of lyrical content, as well as about cultural appropriation and tourism. Article >

In this essay, Gussow focuses on how blues music names the wounding inflicted by white supremacy on African Americans in the Deep South. Mississippi is the birthplace not only of blues music, Gussow argues, but also of blues feeling, “a whole complex of emotions and attitudes engendered in its African American residents” (36). He looks at the complex relationship between blues as counter culture and at its evolution as a form of cultural tourism in Mississippi. Gussow acknowledges that “blues tourism” can be seen as one more way “white capital extracts profit from black artistry without truly sharing in the wealth” (36). But he also points to instances of how African Americans are helping generate and are capitalizing on this wave of cultural tourism. Gussow is careful to concede that contemporary local blues scenes can be sites fraught with essentializing when white audiences and participants come looking for authentic black experiences and expressions. But he argues that such scenes can also be places of redemption, since they attract loving attention to the blues. And here, he draws on bell hooks, who, he contends, holds the “master key” to the blues: “…to have the blues is to be wounded in the place where we would know—or have known—love” (41). This essay provides an excellent way to open conversations about the blues as musical genre, and particularly about the meaning of lyrical content, as well as about cultural appropriation and tourism. Article >

John Lee Hooker, courtesy of Wilson Library’s Southern Folklife Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“Redneck Woman” and the Gendered Poetics of Class Rebellion

Nadine Hubbs, Vol. 17, No. 4 (Winter 2011)

Hubbs looks at the identity politics of country music and working-class culture through the lens of Gretchen Wilson’s 2004 hit single “Redneck Woman.” She situates Wilson and her song in the context of other country performers who foreground working-class pride as well as against the established gender and class identity of the “virile female,” (blue collar, partier, strongly male-identified) (59). The images of white working-class women in Wilson’s song as well as her own multi-media persona are defiantly “anti-bourgeois,” and talk back to the middle class and its “self-affirming power” (63). Hubbs’ use of the work of social class theorists such as Sherry Ortner and Pierre Bourdieu in crafting her arguments is quite clear and accessible and leads smoothly into one of the biggest contributions of this essay: Country music consumption, she argues, is less about demographics and more about identifications, which are shaped by “unseen factors,” such as “yearnings and denials” (53). This is true of all popular music—indeed all consumption generally—and is a good concept for students to chew on. This essay would be an excellent way to open conversations about country music, social class, identity and female subjectivities in America. (Could be paired with Huber’s A Short History of ‘Redneck’: The Fashioning of a Southern White Masculine Identity, Vol. 1, No. 2, Winter 1995). Article >

Hubbs looks at the identity politics of country music and working-class culture through the lens of Gretchen Wilson’s 2004 hit single “Redneck Woman.” She situates Wilson and her song in the context of other country performers who foreground working-class pride as well as against the established gender and class identity of the “virile female,” (blue collar, partier, strongly male-identified) (59). The images of white working-class women in Wilson’s song as well as her own multi-media persona are defiantly “anti-bourgeois,” and talk back to the middle class and its “self-affirming power” (63). Hubbs’ use of the work of social class theorists such as Sherry Ortner and Pierre Bourdieu in crafting her arguments is quite clear and accessible and leads smoothly into one of the biggest contributions of this essay: Country music consumption, she argues, is less about demographics and more about identifications, which are shaped by “unseen factors,” such as “yearnings and denials” (53). This is true of all popular music—indeed all consumption generally—and is a good concept for students to chew on. This essay would be an excellent way to open conversations about country music, social class, identity and female subjectivities in America. (Could be paired with Huber’s A Short History of ‘Redneck’: The Fashioning of a Southern White Masculine Identity, Vol. 1, No. 2, Winter 1995). Article >

Gretchen Wilson, photo courtesy of www.gretchenwilson.com.

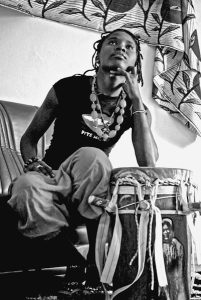

The New Masters of Eloquence: Southernness, Senegal, and Transatlantic Hip-Hop Mobilities

Ali Colleen Neff, Vol. 19, No. 1 (Spring 2013)

In this expansive essay, Neff situates three Senegalese hip-hop artists (Akon, Toussa, and Pape Ndiaye Thiopet) and their music in the context of “the Black Atlantic,” an Afrodiasporic aesthetic world (8). Further, Neff demonstrates the ways these artists identify with, draw on and contribute to a hip-hop sound and a conceptual place known as the Dirty South, a “thick place,” where Africans and African Americans mix their lives in southern cities, such as Atlanta, and their artistic production in “transatlantic” conversations. Neff identifies the qualities that make up the Dirty South hip-hop sound (i.e., digital production, brassy car sound systems, hustler lyricism) and teases out the “Wolof rhythms” and griot sensibilities these Senegalese artists bring to the sound in performance (22). “Americanness and Africanness,” Neff maintains, “Have always been bound with each other on the grounds of the Global South” (23). Neff’s essay kicks the door open to conversations about this richly layered and historically tumultuous ground. It is an excellent way to introduce students to genres of American hip-hop, the music’s global influence, the concept of the Black Atlantic, and to West African popular music and aesthetics. Article >

In this expansive essay, Neff situates three Senegalese hip-hop artists (Akon, Toussa, and Pape Ndiaye Thiopet) and their music in the context of “the Black Atlantic,” an Afrodiasporic aesthetic world (8). Further, Neff demonstrates the ways these artists identify with, draw on and contribute to a hip-hop sound and a conceptual place known as the Dirty South, a “thick place,” where Africans and African Americans mix their lives in southern cities, such as Atlanta, and their artistic production in “transatlantic” conversations. Neff identifies the qualities that make up the Dirty South hip-hop sound (i.e., digital production, brassy car sound systems, hustler lyricism) and teases out the “Wolof rhythms” and griot sensibilities these Senegalese artists bring to the sound in performance (22). “Americanness and Africanness,” Neff maintains, “Have always been bound with each other on the grounds of the Global South” (23). Neff’s essay kicks the door open to conversations about this richly layered and historically tumultuous ground. It is an excellent way to introduce students to genres of American hip-hop, the music’s global influence, the concept of the Black Atlantic, and to West African popular music and aesthetics. Article >

Sister Coumbis, a member of the Senegalese music group GOTAL, photographed by Ali Colleen Neff.

John Elkington and the Remaking of Beale Street

by Cathryn Stout, Vol. 21, No. 3 (Fall 2015)

Stout’s essay includes a concise introduction to an interview she conducted in 2011 with John Elkington, the white real-estate developer who spear-headed the revitalization of Beale Street. In excerpts from the interview, we learn of Elkington’s appointment to the Beale Street Historic Foundation in the early 1970s and how his firm, Elkington and Keltner, got involved in the redevelopment of Beale Street in the 1980s. He describes in general terms talking to people in the black community about what they wanted to see on Beale Street, which, he asserts, was a recreation of the way it had been in the 1950s. Elkington describes how he envisioned things for Beale Street in an era of integration, with hopes for black business ownership. His brief descriptions of a very complex and controversial process provide good jumping off points for deeper discussions about the race and class dynamics of urban renewal and gentrification. And the fact that Stout never mentions the race of the white man who led redevelopment efforts on Beale Street, a vital African American urban center in the first half of the twentieth century, is likewise discussion worthy. This omission communicates tacit assumptions about who leads urban redevelopment and even about the essay’s anticipated readership. Article >

Stout’s essay includes a concise introduction to an interview she conducted in 2011 with John Elkington, the white real-estate developer who spear-headed the revitalization of Beale Street. In excerpts from the interview, we learn of Elkington’s appointment to the Beale Street Historic Foundation in the early 1970s and how his firm, Elkington and Keltner, got involved in the redevelopment of Beale Street in the 1980s. He describes in general terms talking to people in the black community about what they wanted to see on Beale Street, which, he asserts, was a recreation of the way it had been in the 1950s. Elkington describes how he envisioned things for Beale Street in an era of integration, with hopes for black business ownership. His brief descriptions of a very complex and controversial process provide good jumping off points for deeper discussions about the race and class dynamics of urban renewal and gentrification. And the fact that Stout never mentions the race of the white man who led redevelopment efforts on Beale Street, a vital African American urban center in the first half of the twentieth century, is likewise discussion worthy. This omission communicates tacit assumptions about who leads urban redevelopment and even about the essay’s anticipated readership. Article >

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (left) and A. W. Willis Jr. (backseat) ride down Beale Street on July 31, 1959. Photo by Ernest Withers, courtesy of the Miriam DeCosta Willis Collection / Memphis Public Library and Information Center.

To the Land I Am Bound: A Journey into Sacred Harp

David L. Carlton, Vol. 9, No. 2 (Summer 2003)

Carlton opens his essay with a description of the Lookout Mountain Sacred Harp Singing Convention he attended. Here he introduces readers to the spatial arrangement for singing—in a square, where the leader stands in the middle—to the way singers sing to one another and not for an audience, and to some of the changes that have come to shape-note singing in recent years. Not everyone who participates is rural or southern anymore, and “lessons,” as singing gatherings are called, are now announced online through interest groups and church websites, complete with driving directions and maps. Carlton moves easily from personal experience into a musicologically sound yet completely accessible cultural history of Sacred Harp singing. And he points to key resources for further exploration into the musical genre: documentaries, such as “Sweet is the Day,” which feature the large and well-known Wootten family; song books, such as “The Colored Sacred Harp,” which has been a staple of African American singings since its publication in 1934; and recordings, such as “In Sweetest Union Join,” a recording of the 1999 United Sacred Harp Musical Association convention. Carlton’s essay is a great introduction to this unaccompanied shape-note tradition and concludes with an excellent resource list for further multi-media learning on the topic. Article >

Carlton opens his essay with a description of the Lookout Mountain Sacred Harp Singing Convention he attended. Here he introduces readers to the spatial arrangement for singing—in a square, where the leader stands in the middle—to the way singers sing to one another and not for an audience, and to some of the changes that have come to shape-note singing in recent years. Not everyone who participates is rural or southern anymore, and “lessons,” as singing gatherings are called, are now announced online through interest groups and church websites, complete with driving directions and maps. Carlton moves easily from personal experience into a musicologically sound yet completely accessible cultural history of Sacred Harp singing. And he points to key resources for further exploration into the musical genre: documentaries, such as “Sweet is the Day,” which feature the large and well-known Wootten family; song books, such as “The Colored Sacred Harp,” which has been a staple of African American singings since its publication in 1934; and recordings, such as “In Sweetest Union Join,” a recording of the 1999 United Sacred Harp Musical Association convention. Carlton’s essay is a great introduction to this unaccompanied shape-note tradition and concludes with an excellent resource list for further multi-media learning on the topic. Article >

“Nice to Meet You, Three, Four”: New Orleans Musicians and the Attractions of Community

Michael Urban, Vol. 21, No. 3 (Fall 2015)

Drawing substantially from interviews he conducted, Urban elucidates the community values essential to identifying as a New Orleans musician. While being born into a musical family in New Orleans and/or having grown up in a musical neighborhood in the city are common backstories for native musicians, transplants also have access to the community. “[A] New Orleans musician,” Urban writes. “Is someone recognized by others as such because he or she engages in specific practices and abides by certain norms of the city’s musical community” (77). Among the norms are a passion for playing music rather than a fixation on commercial success; versatility with musical styles and instruments and a willingness to play with different bands; respect for others, demonstrated in part by not playing over them when improvising; and understanding of the culture of favors and reciprocity. Urban’s essay is a good introduction to the concept of community generally and opens opportunities for identifying and discussing the norms and practices of other musical communities. Article >

Drawing substantially from interviews he conducted, Urban elucidates the community values essential to identifying as a New Orleans musician. While being born into a musical family in New Orleans and/or having grown up in a musical neighborhood in the city are common backstories for native musicians, transplants also have access to the community. “[A] New Orleans musician,” Urban writes. “Is someone recognized by others as such because he or she engages in specific practices and abides by certain norms of the city’s musical community” (77). Among the norms are a passion for playing music rather than a fixation on commercial success; versatility with musical styles and instruments and a willingness to play with different bands; respect for others, demonstrated in part by not playing over them when improvising; and understanding of the culture of favors and reciprocity. Urban’s essay is a good introduction to the concept of community generally and opens opportunities for identifying and discussing the norms and practices of other musical communities. Article >

Charmaine Neville backstage at Snug Harbor between sets at her regular Monday night gig. Photo by Michael Urban.

Country Music Stars

Jocelyn Neal, Vol. 15, No. 3 (Fall 2009)

Neal is a country music scholar, and the breadth and depth of her knowledge about the genre shines through in this fun top-ten list of great country music stars. Her concise introduction points to one of the great tensions within country music: commercial success vis-à-vis authenticity. Neal notes that some of the individuals in her list have come under attack for crossing genre borders and expresses a desire to “spark conversations about all the greats who don’t appear” on her list (71). Garth Brooks, who, Neal points out, “never apologized for listening to as much Journey and Bruce Springsteen…as George Jones and George Strait,” is there. And country doyenne Dolly Parton is on the list. “Parton,” Neal writes, “simultaneously represented all that is country music and disregarded all the conventional limitations of the genre” (72). The Dixie Chicks, Loretta Lynn, and Jimmie Rodgers also make the cut, and Neal will convince you that they belong there. This essay provides an historical window into the development of country music (Jimmie Rodgers through Dixie Chicks) and is a great way to open conversations about country music as a genre as well as about the central issue of authenticity. Article >

Neal is a country music scholar, and the breadth and depth of her knowledge about the genre shines through in this fun top-ten list of great country music stars. Her concise introduction points to one of the great tensions within country music: commercial success vis-à-vis authenticity. Neal notes that some of the individuals in her list have come under attack for crossing genre borders and expresses a desire to “spark conversations about all the greats who don’t appear” on her list (71). Garth Brooks, who, Neal points out, “never apologized for listening to as much Journey and Bruce Springsteen…as George Jones and George Strait,” is there. And country doyenne Dolly Parton is on the list. “Parton,” Neal writes, “simultaneously represented all that is country music and disregarded all the conventional limitations of the genre” (72). The Dixie Chicks, Loretta Lynn, and Jimmie Rodgers also make the cut, and Neal will convince you that they belong there. This essay provides an historical window into the development of country music (Jimmie Rodgers through Dixie Chicks) and is a great way to open conversations about country music as a genre as well as about the central issue of authenticity. Article >