The following essays are about protest. In a few pieces, protest is explicit: the Lumbee protest against the KKK rally in 1958 in Robeson County, North Carolina; the mill worker strike and accompanying protest songs in Gastonia, North Carolina, in the late 1920s; and the statewide outcry in Alabama against HB 56, which sought to restrict the rights of immigrants there. In other cases, protest is implicit: the words of coastal residents in North Carolina as they describe in very apolitical terms the way climate change is altering their home communities and ways of life; and descriptions of Chapel Hill restauranteur Vimala Rajendran’s insistence on feeding the hungry, whether they can pay or not. Indeed, we might say that most essays in Southern Cultures have a protest angle, since they tend to push back—explicitly or implicitly—against facile assumptions about southerners. With this following group of essays, students may be encouraged to explore assumptions, push-back about what it has meant—and continues to mean—to want change in the South and beyond.

We might say that most essays in Southern Cultures have a protest angle, since they tend to push back—explicitly or implicitly—against facile assumptions about southerners.

The Media, the Klan, and the Lumbees of North Carolina

Christopher Arris Oakley, Vol. 14, No. 4 (Winter 2008)

Oakley’s essay details the events of a large Lumbee protest and ultimate victory over members of the KKK at a rally near Maxton in Robeson County in 1958. In the process, Oakley concisely describes the tri-partite system of segregation in Robeson County, places Lumbees within historical context as a Southeastern Indian culture group, and demonstrates how enthusiastic media attention after the 1958 protest perpetuated harmful stereotypes. Lumbee men, dressed like their contemporaries around the nation in pants, jackets and the derby hats popular at the time, were said to have “whooped” and gone on the “warpath,” to have started a “riot,” and were described as Cherokee in several accounts. Oakley includes testimonies from individual Lumbees who were at the rally. Their recollections contrast with sensational media accounts and also illustrate how punishing the system of segregation was to everyday life. Oakley also provides a brief but thought-provoking contrast between media responses to the Lumbee protest with that of an African American protest against the KKK in Union County in 1957. “The media response to [a] defensive use of violence by African Americans against the Klan was not nearly as celebrated as the Lumbee’s victory” (79). This is an excellent essay for opening discussions about Lumbee and Southeastern Indian culture and history; systems of segregation; representation; and violence and protest in the South.

Oakley’s essay details the events of a large Lumbee protest and ultimate victory over members of the KKK at a rally near Maxton in Robeson County in 1958. In the process, Oakley concisely describes the tri-partite system of segregation in Robeson County, places Lumbees within historical context as a Southeastern Indian culture group, and demonstrates how enthusiastic media attention after the 1958 protest perpetuated harmful stereotypes. Lumbee men, dressed like their contemporaries around the nation in pants, jackets and the derby hats popular at the time, were said to have “whooped” and gone on the “warpath,” to have started a “riot,” and were described as Cherokee in several accounts. Oakley includes testimonies from individual Lumbees who were at the rally. Their recollections contrast with sensational media accounts and also illustrate how punishing the system of segregation was to everyday life. Oakley also provides a brief but thought-provoking contrast between media responses to the Lumbee protest with that of an African American protest against the KKK in Union County in 1957. “The media response to [a] defensive use of violence by African Americans against the Klan was not nearly as celebrated as the Lumbee’s victory” (79). This is an excellent essay for opening discussions about Lumbee and Southeastern Indian culture and history; systems of segregation; representation; and violence and protest in the South.

The photograph of Charlie Warriax (left) and Simeon Oxendine (right) wearing the captured KKK banner around their shoulders became the dominant image and symbol of the Lumbees’ victory over the Klan. Courtesy of the Charlotte Observer Photograph Collection, Public Library of Charlotte & Mecklenburg County.

“Battle Songs of the Southern Class Struggle”: Songs of Gastonia Textile Strike of 1929

Patrick Huber, Vol 4, No. 2 (Summer 1998)

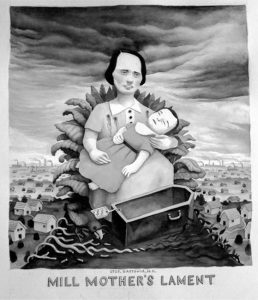

Huber looks at the central role of protest songs in mill workers’ strikes of the 1920s. Loray Mill in Gastonia, North Carolina, was one of the largest textile mills in the world and the months-long strike there in 1929 made headlines. The National Textile Workers Union got involved and the strike was violent and bloody. Striking mill workers drew on a long tradition of southern balladry and contemporary “hillbilly” music to craft songs expressly for the strike. Ella May Wiggins, a tragic casualty of the violence, was one of the most central and prolific composers and singers. She “transformed personal experience into universal songs that spoke directly to other textile workers—especially mill mothers” (119). Huber includes the lyrics to “Mill Mother’s Song,” Wiggins’ most well-known ballad, which gained wide-spread popularity several decades later during the folk music revival. Huber demonstrates the ways in which mill workers were part of a “mass culture of consumption,” as evidenced by Wiggins’ and other’s knowledge of contemporary popular music. “Collectively, the Gastonia strike songs not only reveal the inner story of that famous labor conflict, they also shatter stereotypes of southern textile workers and illuminate the ways in which modernity shaped their lives and identities” (121). This essay provides good historic context for Piedmont textile mill strikes and more generally introduces students to southern labor and women’s history and opens the way for conversations about song as protest.

Huber looks at the central role of protest songs in mill workers’ strikes of the 1920s. Loray Mill in Gastonia, North Carolina, was one of the largest textile mills in the world and the months-long strike there in 1929 made headlines. The National Textile Workers Union got involved and the strike was violent and bloody. Striking mill workers drew on a long tradition of southern balladry and contemporary “hillbilly” music to craft songs expressly for the strike. Ella May Wiggins, a tragic casualty of the violence, was one of the most central and prolific composers and singers. She “transformed personal experience into universal songs that spoke directly to other textile workers—especially mill mothers” (119). Huber includes the lyrics to “Mill Mother’s Song,” Wiggins’ most well-known ballad, which gained wide-spread popularity several decades later during the folk music revival. Huber demonstrates the ways in which mill workers were part of a “mass culture of consumption,” as evidenced by Wiggins’ and other’s knowledge of contemporary popular music. “Collectively, the Gastonia strike songs not only reveal the inner story of that famous labor conflict, they also shatter stereotypes of southern textile workers and illuminate the ways in which modernity shaped their lives and identities” (121). This essay provides good historic context for Piedmont textile mill strikes and more generally introduces students to southern labor and women’s history and opens the way for conversations about song as protest.

Phil Blank, Mill Mother’s Lament, 2015, from the series Southern Insurrections.

Learning from the Long Civil Rights Movement’s First Generation: Virginia Durr

From interviews by M. Sue Thrasher, Jacquelyn Dowd Hall and Bob Hall, compiled and introduced by Sarah Theusen, Vol. 16, No. 2 (Summer 2010)

Sarah Theusen’s introduction to excerpts from oral history interviews with Virginia Durr sets the historical context for understanding Durr’s position as “a living embodiment of . . . the ‘Long Civil Rights Movement.’” (73). Durr’s own words from the interviews paint a picture of an unlikely activist—a white Alabaman with slave-holding, aristocratic roots, groomed at private schools in the northeast and married to a successful attorney. Yet Durr was an ardent anti-segregationist. She became a founding member in 1938 of the Southern Conference for Human Welfare, an anti-segregation organization which promoted voter registration and advocated for the abolishment of poll taxes. Her affiliation with places such as the Highlander Research and Education Center, where hundreds of civil rights activists trained, the Southern Conference for Human Welfare, and the Progressive Party caused her to be called before Senator Jim Eastland’s anti-communist committee in the 1950s. “Everybody knew I was against segregation,” said Durr. “I suppose some people thought I was a Communist and a dangerous person, too” (81). Durr’s words about her life and work are frank and reveal her generational and societal biases as well as her broad-mindedness. This essay offers an opportunity to explore the concept of the “Long Civil Rights Movement” as well as women’s roles in civil rights activism and the importance of the Southern Oral History Program’s large collection of archived interviews on the topic.

Sarah Theusen’s introduction to excerpts from oral history interviews with Virginia Durr sets the historical context for understanding Durr’s position as “a living embodiment of . . . the ‘Long Civil Rights Movement.’” (73). Durr’s own words from the interviews paint a picture of an unlikely activist—a white Alabaman with slave-holding, aristocratic roots, groomed at private schools in the northeast and married to a successful attorney. Yet Durr was an ardent anti-segregationist. She became a founding member in 1938 of the Southern Conference for Human Welfare, an anti-segregation organization which promoted voter registration and advocated for the abolishment of poll taxes. Her affiliation with places such as the Highlander Research and Education Center, where hundreds of civil rights activists trained, the Southern Conference for Human Welfare, and the Progressive Party caused her to be called before Senator Jim Eastland’s anti-communist committee in the 1950s. “Everybody knew I was against segregation,” said Durr. “I suppose some people thought I was a Communist and a dangerous person, too” (81). Durr’s words about her life and work are frank and reveal her generational and societal biases as well as her broad-mindedness. This essay offers an opportunity to explore the concept of the “Long Civil Rights Movement” as well as women’s roles in civil rights activism and the importance of the Southern Oral History Program’s large collection of archived interviews on the topic.

Virginia Foster Durr, with son Clifford, who died at age three, and daughter Lucy, born in 1937, courtesy of the Birmingham Public Library Archives.

“No Juan Crow!”: Documenting the Immigration Debate in Alabama Today

Jennifer Brooks, Vol. 18, No. 3 (Fall 2012)

Brooks’s essay is a vivid reminder of the long and on-going struggle for immigrants’ rights in the United States. The photos here feature a wide range of community protests in response to Republican majority House Bill 56, which Alabama Governor Robert J. Bentley signed in June of 2011. The bill required, among other things, for public schools to check the immigration status of in-coming students and mandated police officers to check the immigration status of someone stopped for even minor offenses. The Department of Justice, community, civil and religious groups, as well as the Alabama ACLU and the Southern Poverty Law Center, sued to prevent implementation of the Bill. Brooks’s text along with the photographs of protests position current immigrant struggles squarely within the “Long Civil Rights Movement.” Images feature protestors walking past the church where Martin Luther King, Jr. was pastor at the time of the Montgomery Bus Boycott and also show protestors holding placards with an image of King reading, “OBAMA: Honor King’s Dream.” A large banner shows a Hispanic Rosie the Riveter with the words “Brown is Beautiful.” Brooks notes: “I was struck by how Alabama’s Hispanic participants drew on the state’s civil rights history, as well as their own sense of regional and national identity, to challenge the legitimacy of HB 56” (52). This essay is a good companion to discussions of current discriminatory immigration policies in the United States, as well as to broader discussions of civil rights activism in the South.

Brooks’s essay is a vivid reminder of the long and on-going struggle for immigrants’ rights in the United States. The photos here feature a wide range of community protests in response to Republican majority House Bill 56, which Alabama Governor Robert J. Bentley signed in June of 2011. The bill required, among other things, for public schools to check the immigration status of in-coming students and mandated police officers to check the immigration status of someone stopped for even minor offenses. The Department of Justice, community, civil and religious groups, as well as the Alabama ACLU and the Southern Poverty Law Center, sued to prevent implementation of the Bill. Brooks’s text along with the photographs of protests position current immigrant struggles squarely within the “Long Civil Rights Movement.” Images feature protestors walking past the church where Martin Luther King, Jr. was pastor at the time of the Montgomery Bus Boycott and also show protestors holding placards with an image of King reading, “OBAMA: Honor King’s Dream.” A large banner shows a Hispanic Rosie the Riveter with the words “Brown is Beautiful.” Brooks notes: “I was struck by how Alabama’s Hispanic participants drew on the state’s civil rights history, as well as their own sense of regional and national identity, to challenge the legitimacy of HB 56” (52). This essay is a good companion to discussions of current discriminatory immigration policies in the United States, as well as to broader discussions of civil rights activism in the South.

A July 2011 Interfaith Vigil in protest of HB 56 passed the church, photographed by Darrell Crutchley.

“There Can Be No Business as Usual”: The University of North Carolina and the Student Strike of May 1970

Christopher Broadhurst, Vol. 21, No. 2 (Summer 2015)

When President Nixon declared his plan to escalate the Vietnam War by sending thousands of troops to Cambodia, protests erupted on campuses across the nation. After four students were killed by National Guard troops on May 4, 1970 at a demonstration at Kent State, campus protests grew in scope and in coordination. Broadhurst’s essay situates the two-week student strike in May of 1970 at the University of North Carolina within this historic context as well as within what he describes as a decade-long rise in campus activism there. Southern campuses, Broadhurst points out, had not been noted for contributing much to the protests of 1970, as the South was seen as supportive of martial culture and the war in Vietnam generally. With historic photographs mined from the UNC libraries and detailed descriptions of the events of the strike itself, Broadhurst demonstrates quite vividly how students at the University of North Carolina were deeply embedded in anti-war protest culture.

When President Nixon declared his plan to escalate the Vietnam War by sending thousands of troops to Cambodia, protests erupted on campuses across the nation. After four students were killed by National Guard troops on May 4, 1970 at a demonstration at Kent State, campus protests grew in scope and in coordination. Broadhurst’s essay situates the two-week student strike in May of 1970 at the University of North Carolina within this historic context as well as within what he describes as a decade-long rise in campus activism there. Southern campuses, Broadhurst points out, had not been noted for contributing much to the protests of 1970, as the South was seen as supportive of martial culture and the war in Vietnam generally. With historic photographs mined from the UNC libraries and detailed descriptions of the events of the strike itself, Broadhurst demonstrates quite vividly how students at the University of North Carolina were deeply embedded in anti-war protest culture.

On May 6, 1970, 6,000 students gathered in Polk Place, the central quad on the UNC campus, to listen to Tommy Bello, student body president, and other students launch the student strike. Following this initial gathering, 4,000 students went on to march through Chapel Hill. One poignant photograph featured in the essay shows student protestors on Franklin Street carrying coffins to represent the four dead at Kent State. Largely non-violent, strikers did damage some property, including Silent Sam, the contentious statue of a Confederate soldier that stood at an entrance to the UNC campus until this fall, when student protestors pulled it down. The damage to Silent Sam in 1970? Someone spray-painted NIXON across the statue, with a swastika used for the “X.” This essay is useful for generating discussions about historic and on-going campus activism and about the power of student protest in generating larger social change.

“Anti-War demonstrators on Franklin St,” University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill collection, Photographic Archives, University of North Carolina Libraries.”

RISING: Perspectives of Change on the North Carolina Coast

Introduction and photographs by Baxter Miller, Interviews by Ryan Stancil and Barbara Garrity Blake, Vol. 24, No. 1 (Spring 2018)

With exquisite photographs of a changing coastline and of the people who make their lives there, this essay shows the realities of climate change and sea-level rise. In her introduction, Miller describes the ways in which people have tried to alter the inherently “dynamic” North Carolina coastline in order to make it more habitable and appealing to tourists. “Advances in technology, engineering, and construction, along with commercial and economic realizations, have shifted our adaptive ideology on our barrier islands and across coastal North Carolina,” writes Miller. “Today we build higher dunes and more jetties. We harden our shorelines and seawalls. We dredge our inlets and re-nourish our eroded beaches” (102).

With exquisite photographs of a changing coastline and of the people who make their lives there, this essay shows the realities of climate change and sea-level rise. In her introduction, Miller describes the ways in which people have tried to alter the inherently “dynamic” North Carolina coastline in order to make it more habitable and appealing to tourists. “Advances in technology, engineering, and construction, along with commercial and economic realizations, have shifted our adaptive ideology on our barrier islands and across coastal North Carolina,” writes Miller. “Today we build higher dunes and more jetties. We harden our shorelines and seawalls. We dredge our inlets and re-nourish our eroded beaches” (102).

The photographs and interview excerpts reveal the ways coastal residents cope, adapt, and watch as their environment rapidly changes. For example, “Remains of the Hatteras Inlet Lifesaving Station, Ocracoke, Dare County” shows wooden piers that once supported a beach-side lifesaving station lapped by shallow, green waters, almost completely reclaimed by the sea (106). The photograph entitled “Patricia Smith, North River and Laurel Road, Cateret County” features Ms. Smith standing in the middle of the road in her neighborhood which now floods regularly. “I told them, ‘Well, in ten to twenty year,’ I said . . . ’ North River and Laurel Road’s going to be gone’” (112). Dawn Taylor’s words are a haunting accompaniment to an aerial view of her family’s cemetery, reinforced with sandbags against an encroaching ocean: “With every West wind, every storm . . . it’s just sand, you know, it goes out with the tide. And so do the remains of your loved ones” (114). This powerful photo essay provides a way to open conversations about coastal culture and environment; coastal tourism and commercial development; and climate change and its casualties.

Photograph by Baxter Miller.

Vimala Cooks, Everybody Eats

Shannon Harvey, Vol. 18, No. 2 (Summer 2012)

Harvey’s photo essay celebrates Vimala Rajendran’s giving spirit while at the same time, drawing attention to a non-confrontational and steady and quiet form of protest. Rajendran’s slogan for her Curryblossom Café, a successful restaurant in downtown Chapel Hill, is “Vimala Cooks, Everybody Eats.” It means that Rajendran never turns anyone away who does not have the means to pay for a meal. After leaving an abusive relationship, Rajendran began making community dinners out of her brick ranch house in Chapel Hill to make ends meet. Volunteers helped with food preparation and everyone who attended ate, regardless of the amount they could donate for a meal. Vimala’s Curryblossom Café is the outgrowth of years of this kind of community-building through food. And the locally sourced, vegetarian dishes she prepares there daily are still available to anyone who is hungry. This photo essay is a great way to encourage conversations about food insecurity and sustainability; food and community; and food and social justice. (See also, WUNC’s “’Storymakers Durham’: A Restaurant with a Mission.”)

Harvey’s photo essay celebrates Vimala Rajendran’s giving spirit while at the same time, drawing attention to a non-confrontational and steady and quiet form of protest. Rajendran’s slogan for her Curryblossom Café, a successful restaurant in downtown Chapel Hill, is “Vimala Cooks, Everybody Eats.” It means that Rajendran never turns anyone away who does not have the means to pay for a meal. After leaving an abusive relationship, Rajendran began making community dinners out of her brick ranch house in Chapel Hill to make ends meet. Volunteers helped with food preparation and everyone who attended ate, regardless of the amount they could donate for a meal. Vimala’s Curryblossom Café is the outgrowth of years of this kind of community-building through food. And the locally sourced, vegetarian dishes she prepares there daily are still available to anyone who is hungry. This photo essay is a great way to encourage conversations about food insecurity and sustainability; food and community; and food and social justice. (See also, WUNC’s “’Storymakers Durham’: A Restaurant with a Mission.”)