Food is the door through which Bernard L. Herman brings readers to deep human ecologies of the Eastern Shore of Virginia. From large, dark drum fish to the little shimmery spot to eels to oysters and corn, from “marsh to field to table,” Herman listens carefully, partakes heartily, and responds poetically to the sense of belonging food engenders in these coastal communities. His methods are ethnographic, and while his writing is delightfully free of scholarly jargon, he has honed the concept of terroir to a theoretical framework. Used by French wine growers to describe how locale affects the taste of wine, terroir has come to mean “taste of place.” For Herman terroir goes beyond soil and taste to include story and experience, a consuming process through which local residents reinforce their place-based identities and are able to share them with others. Herman’s essays about Eastern Shore foodways grow out of years of experience living, working (he raises oysters in addition to researching and writing), and being in the community.

His following five essays from Southern Cultures make three things clear:

- The delicate ecology of local communities

- The depth of meaning in one food

- The layers of local knowledge unearthed by attention to symbolic forms

Read separately or together, these pieces will inspire discussion of how to write about food and place.

Drum Head Stew: The Power and Poetry of Terroir

Vol. 15, No. 4 (Summer 2009)

This is the first of four essays Herman has published in Southern Cultures about communities on the Eastern Shore of Virginia, “a long, narrow peninsula that projects roughly seventy miles southward from the Maryland state line to the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay” (37). Here, Herman introduces terroir, a concept that “defines particular attributes of a place embodied in cuisine and narrated through words and actions and objects” (36). Herman foregrounds one local delicacy (drum fish), and through excerpts from interviews and conversations, his own documentary photographs, and secondary sources that describe the locale, he shows how food and story invite everyone to partake of a place. Herman’s work is always richly illustrated, elegantly written, and accessible. Recipes for drum fish stew, gathered by Herman from local residents, stand out like poetry in the body of the essay. But his is not just pretty food writing. Herman acknowledges the poverty and the threats of big commercial farming and fishing and real estate development to the cohesion of this fragile coastal wetland and its cultures. Foodways, he asserts, and the stories that go with them, “provide the core elements for sustainable economic development rooted in human ecology” (37).

This is the first of four essays Herman has published in Southern Cultures about communities on the Eastern Shore of Virginia, “a long, narrow peninsula that projects roughly seventy miles southward from the Maryland state line to the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay” (37). Here, Herman introduces terroir, a concept that “defines particular attributes of a place embodied in cuisine and narrated through words and actions and objects” (36). Herman foregrounds one local delicacy (drum fish), and through excerpts from interviews and conversations, his own documentary photographs, and secondary sources that describe the locale, he shows how food and story invite everyone to partake of a place. Herman’s work is always richly illustrated, elegantly written, and accessible. Recipes for drum fish stew, gathered by Herman from local residents, stand out like poetry in the body of the essay. But his is not just pretty food writing. Herman acknowledges the poverty and the threats of big commercial farming and fishing and real estate development to the cohesion of this fragile coastal wetland and its cultures. Foodways, he asserts, and the stories that go with them, “provide the core elements for sustainable economic development rooted in human ecology” (37).

George Doughty hunting shorebirds on the Hog Island beach, c. 1900, courtesy of Buck and Helene Doughty.

Theodore Peed’s Turtle Party

Vol. 18, No. 2 (Summer 2012)

Here, Herman introduces readers to Theodore Peed, who hosts his entire community annually in the fall of the year for a feast of wild game—turtle, venison, fish. At Peed’s party, attendees congregate in a garage-turned-banquet-hall and reinforce their social ties as they mix and mingle, eat local food (marsh hens, grits, sea bass), and talk about the work and the rhythms integral to the production of that food. Herman foregrounds residents’ own talk to reveal ecologies and their signifying nomenclature. For example, Peed makes passing mention of “signing” for turtles, a hand-fishing technique that relies on attention to little bubbles on the surface of the water, indicating a turtle in the mud below. It is knowledge that demonstrates the intricate play between culture and environment, the sort that reveals itself only through time and with careful attention to what people say and do. Peed’s descriptions of the African kettles he uses and the turtle meat preferences among white and black residents in the region connect his foodways to “complex social networks along the Eastern Shore of Virginia for 400 years” (66).

Here, Herman introduces readers to Theodore Peed, who hosts his entire community annually in the fall of the year for a feast of wild game—turtle, venison, fish. At Peed’s party, attendees congregate in a garage-turned-banquet-hall and reinforce their social ties as they mix and mingle, eat local food (marsh hens, grits, sea bass), and talk about the work and the rhythms integral to the production of that food. Herman foregrounds residents’ own talk to reveal ecologies and their signifying nomenclature. For example, Peed makes passing mention of “signing” for turtles, a hand-fishing technique that relies on attention to little bubbles on the surface of the water, indicating a turtle in the mud below. It is knowledge that demonstrates the intricate play between culture and environment, the sort that reveals itself only through time and with careful attention to what people say and do. Peed’s descriptions of the African kettles he uses and the turtle meat preferences among white and black residents in the region connect his foodways to “complex social networks along the Eastern Shore of Virginia for 400 years” (66).

Theodore Peed, by Bernard L. Herman.

Eels for Winter

Vol. 20, No. 4 (Winter 2014)

Herman explores his personal experience of trapping eels along the Shore. With his characteristic attention to the details of process, he reveals how trapping and smoking eels mark the advent of the winter season in this place. His description of a day on the water, pulling traps in, icing eels into a coma, bludgeoning, dressing, smoking and eating them demonstrates how entwined local knowledge and natural ecologies are. “I think the eel tastes exactly like winter holidays and the advent of the sleeping season,” writes Herman (137). This kind of embodied experience—a significant way of knowing—is integral to his theory of place.

Herman explores his personal experience of trapping eels along the Shore. With his characteristic attention to the details of process, he reveals how trapping and smoking eels mark the advent of the winter season in this place. His description of a day on the water, pulling traps in, icing eels into a coma, bludgeoning, dressing, smoking and eating them demonstrates how entwined local knowledge and natural ecologies are. “I think the eel tastes exactly like winter holidays and the advent of the sleeping season,” writes Herman (137). This kind of embodied experience—a significant way of knowing—is integral to his theory of place.

Eels, by Bernard L. Herman.

Panfish: Spot On

Vol. 21, No. 1, (Spring 2015)

In “Panfish,” Herman continues the story of complex local ecologies through one plentiful Eastern Shore fish: the spot. Herman presents local classificatory systems for determining if a spot is truly a spot (size, status, procurement), thickly describes “the art of eating fish,” and succinctly notes the ways real estate development and recreational boating impact the place identity inherent in spot culture. The spot—like the drum, like eels—is not just an ingredient, it is a form of local knowledge and a barometer of cultural and environmental rhythms and changes. “The taste for spot,” Herman notes, “is linked to time and place” (102).

In “Panfish,” Herman continues the story of complex local ecologies through one plentiful Eastern Shore fish: the spot. Herman presents local classificatory systems for determining if a spot is truly a spot (size, status, procurement), thickly describes “the art of eating fish,” and succinctly notes the ways real estate development and recreational boating impact the place identity inherent in spot culture. The spot—like the drum, like eels—is not just an ingredient, it is a form of local knowledge and a barometer of cultural and environmental rhythms and changes. “The taste for spot,” Herman notes, “is linked to time and place” (102).

Spot, by Bernard L. Herman.

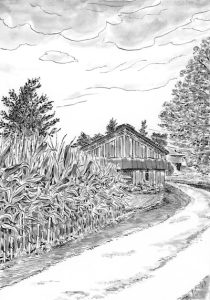

The Scent of Corn

Vol. 23, No. 4 (Winter 2017)

In this homage to field corn, Herman describes a summertime meal with friends on Occahannock Neck, Virginia. The field corn that comes steaming out of a short, hot bath is tasty to human pallets for only one day. How, Herman asks his hosts, do you know which day to pick it? By looking at the corn silks? By checking the color of the kernels? “No,” say the hosts. “It’s the scent of the corn.” What follows is another evocative essay about subtle ways of being in place. Herman’s description of field corn for supper with his friends brings up ways of knowing that go beyond the calendar or visual cues to olfactory sense. This is classic Herman, writing about the place he loves, and fetching correlation from past experience—a day many years ago when he smelled good-to-eat field corn but didn’t yet know what it meant. His essay tells us about the power of the senses to trigger memory and to tell us where we are and what to do.

In this homage to field corn, Herman describes a summertime meal with friends on Occahannock Neck, Virginia. The field corn that comes steaming out of a short, hot bath is tasty to human pallets for only one day. How, Herman asks his hosts, do you know which day to pick it? By looking at the corn silks? By checking the color of the kernels? “No,” say the hosts. “It’s the scent of the corn.” What follows is another evocative essay about subtle ways of being in place. Herman’s description of field corn for supper with his friends brings up ways of knowing that go beyond the calendar or visual cues to olfactory sense. This is classic Herman, writing about the place he loves, and fetching correlation from past experience—a day many years ago when he smelled good-to-eat field corn but didn’t yet know what it meant. His essay tells us about the power of the senses to trigger memory and to tell us where we are and what to do.