The following is a list of frequently read Southern Cultures essays in the classroom from 2016–2017. Why did our readers choose to consult these essays again and again throughout the year? We can’t know for sure. They do point to preoccupations of the present moment—a society grappling with racism and its symbols; political turns of tide. But they also demonstrate the diversity of perspectives found on our pages and among our readership. From American Indian rock ‘n’ roll to women’s behind-the-scenes civil rights work to the invention of southern beaches, we invite you to explore some of that lively variety here.

Elvis Presley and the Politics of Popular Memory

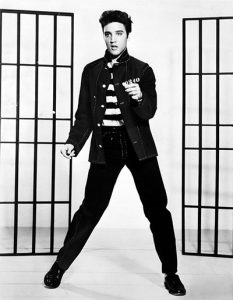

Michael T. Bertrand, Vol. 13, No. 3 (Music 2007)

Bertrand’s essay unveils what every folklorist knows about rumor. They reveal deeply felt anxieties and fears. They are real and true to those who believe them. They are nearly impossible to substantiate. And attempts at debunking them only fan their flames. The rumor at hand in Bertrand’s essay is a racial slur Elvis Presley reportedly uttered: The only thing Blacks could do for him was buy his records and shine his shoes. Ready to believe a working-class white Mississippian would be a racist, Bertrand argues, many African Americans cited the rumor as evidence of Presley’s disregard for the Black culture whose expressive traditions he borrowed so heavily from. Bertrand traces the rumor to a potential source, concluding, however, that Presley’s tenuous reputation among African Americans “was tied to a long-standing and often tragic relationship between black and white people in the western hemisphere” (65). This essay is a great read for anyone interested in rumor; popular culture; history and memory.

A photograph promoting the film Jailhouse Rock depicts singer Elvis Presley, 1957, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The Wildest Show in the South: The Politics and Poetics of the Angola Prison Rodeo and Inmate Arts Festival

Melissa Schrift, Vol. 14, No. 1 (Spring 2008)

Shrift brings an acute anthropological perspective to bear in her essay on the Angola Prison Rodeo. Shrift uses a “public display” framework to analyze the event, which has taken place annually at Louisiana’s State Penitentiary for more than 50 years. Shrift maintains that the rodeo communicates “complex and disturbing messages about crime and incarceration to a curious public” (23). Through close attention to symbolic forms, Shrift identifies several ways in which the rodeo reinforces the sexual and racial politics of this prison and the prison system more generally. Men get locked in sexually suggestive positions as they grasp and fall all over each other in rodeo games. Additionally, the Confederate flag is prominently on display and many African American inmates choose not to participate in the rodeo. Shrift’s final analysis notes that the rodeo and the accompanying Inmate Arts Festival “normalize incarceration” by drawing clear boundaries between the public spectators and the inmate performers and artists and thus reinforcing inmate otherness. This is an excellent essay for students of festival, public display, and symbolic forms.

Angola Prison, November 2009, by msppmoore, courtesy WikiMedia Commons.

“Tiger, Tiger”: Miccosukee Rock-n-Roll

Patsy West and Lee Tiger, Vol. 14, No. 4 (Winter 2008)

In this informative essay about the Miccosukee tribe and the rock band Tiger Tiger, Patsy West and Lee Tiger are likely exposing many readers for the first time to the Miccosukee tribe of South Florida and to Native American rock music. West’s introduction provides a short history of the tribe’s relation to other native peoples of the region, their entrepreneurial engagement with the tourist economy along the Tamiami Highway (U.S. Highway 41), and their nurturing of a vibrant expressive culture. Her profile of Stephen and Lee Tiger, the Miccosukee brothers who started the band Tiger Tiger in the early 1970s, demonstrates how they became spokespeople for the tribe, promoting its arts and history and substantially increasing tourism dollars to Miccosukee communities. An autobiographical essay by Lee Tiger reflects on his career in music with his brother, the influence of their musically gifted and politically powerful father, and the significance of their songs within the genre of Native American rock-n-roll music. This essay is a good resource for American Indian studies; popular culture and music studies; southern studies; and folklore classes.

Stephen (left) and Lee (right) Tiger of “Tiger Tiger,” courtesy of Lee Tiger.

The Sunbelt’s Sandy Foundation: Coastal Development and the Making of the Modern South

Andrew W. Kahrl, Vol. 20, No. 3 (Fall 2014)

Kahrl’s important essay uncovers the power structure behind the development of the coastal south and the wholesale removal of its African American landowning residents. Kahrl crafts a compelling history of the wild, unruly and constantly shifting southern coastline and its transformation to rigidly controlled sandy beaches held in place with federally funded jetties and lined with high-end private real estate developments. Illustrated with examples from North Carolina, Virginia and Florida, Kahrl details the step-by-step process through which the South became the Sunbelt and how the mad rush for coastal property was a large part of its growth. An excellent read for environmental studies; the sociology and history of real estate development; economics; and black land loss.

Kahrl’s important essay uncovers the power structure behind the development of the coastal south and the wholesale removal of its African American landowning residents. Kahrl crafts a compelling history of the wild, unruly and constantly shifting southern coastline and its transformation to rigidly controlled sandy beaches held in place with federally funded jetties and lined with high-end private real estate developments. Illustrated with examples from North Carolina, Virginia and Florida, Kahrl details the step-by-step process through which the South became the Sunbelt and how the mad rush for coastal property was a large part of its growth. An excellent read for environmental studies; the sociology and history of real estate development; economics; and black land loss.

Aerial view of Herbert C. Bonner Bridge, Oregon Inlet, NC, 2009. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Southern Waters: A Visual Perspective

by Bernard Herman and William Arnett, Vol. 20, No. 3 (Fall 2014)

This essay examines the motif of water in the work of Thornton Dial, Ronald Lockett, Georgia Speller, and other southern artists, whose sculpture and paintings Arnett has collected over the course of thirty years and housed at the Souls Grown Deep Foundation in Atlanta, Georgia. Herman is a folklorist and art historian. The captions that accompany each image in the essay are drawn from their years of experience collecting, cataloguing and exhibiting the art and getting to know the artists. Observations and analysis from the artists themselves about their work as well as from Herman and Arnett point to water as a force that has the capacity to give life and to drown it out. This essay reflects one of Southern Culture’s signature strengths—ample space for high-quality representations of southern visual culture. This is a great resource for students of southern and African American art.

This essay examines the motif of water in the work of Thornton Dial, Ronald Lockett, Georgia Speller, and other southern artists, whose sculpture and paintings Arnett has collected over the course of thirty years and housed at the Souls Grown Deep Foundation in Atlanta, Georgia. Herman is a folklorist and art historian. The captions that accompany each image in the essay are drawn from their years of experience collecting, cataloguing and exhibiting the art and getting to know the artists. Observations and analysis from the artists themselves about their work as well as from Herman and Arnett point to water as a force that has the capacity to give life and to drown it out. This essay reflects one of Southern Culture’s signature strengths—ample space for high-quality representations of southern visual culture. This is a great resource for students of southern and African American art.

Georgia Speller, Boat on the River, House on the Hill (1987), tempera and pencil on wood, 18.25 × 30 inches.

Driving Miss Daisy: Southern Jewishness on the Big Screen

by Eliza Russi Lowen McGraw, Vol. 7, No. 2 (Summer 2001)

In her thoughtful essay, Lowen analyzes the precarious social position of southern Jews through the lens of Daisy Werthan, the main character in the 1989 film Driving Miss Daisy. Lowen also pays careful attention to the film’s pairing of Daisy with her African American driver, Hoke. “Through its portrayal of the vulnerability of southern Jewishness,” Lowen notes. “’Miss Daisy’ demonstrates the inseparability of Jewishness and blackness within southern society” (52). To illustrate, Lowen describes a scene in which Hoke and Daisy are stuck in traffic due to the bombing of the Atlanta temple. Her careful attention to the details of this scene illustrates well how Hoke and Daisy are “linked through violence and prejudice” (54). This piece is a useful way to open conversations about southern Jewish identity and about the tropes used to depict the South in film more generally. Excellent essay for use in Jewish studies, film studies, African American studies, and southern studies classrooms.

In her thoughtful essay, Lowen analyzes the precarious social position of southern Jews through the lens of Daisy Werthan, the main character in the 1989 film Driving Miss Daisy. Lowen also pays careful attention to the film’s pairing of Daisy with her African American driver, Hoke. “Through its portrayal of the vulnerability of southern Jewishness,” Lowen notes. “’Miss Daisy’ demonstrates the inseparability of Jewishness and blackness within southern society” (52). To illustrate, Lowen describes a scene in which Hoke and Daisy are stuck in traffic due to the bombing of the Atlanta temple. Her careful attention to the details of this scene illustrates well how Hoke and Daisy are “linked through violence and prejudice” (54). This piece is a useful way to open conversations about southern Jewish identity and about the tropes used to depict the South in film more generally. Excellent essay for use in Jewish studies, film studies, African American studies, and southern studies classrooms.

“I Train the People to do their Own Talking:” Septima Clark and the Women of the Civil Rights Movement

Compiled by David P. Cline, Katherine Mellen Charron, Jacquelyn Dowd Hall, and Eugene P. Walker, Vol. 16, No. 2 (Summer 2010)

This feature essay sheds light on two content strengths of Southern Cultures: oral history and the Civil Rights Movement. While Septima Clark is well known to Civil Rights scholars, she is under-represented in popular knowledge about the Movement. Hall and Walker, who interviewed Septima Clark for the Southern Oral History Program, provide an excellent introduction to Clark’s long-time civil rights work and to the compiled excerpts from the interviews that highlight key moments in her life. In the mid-1950s, Septima Clark was fired from her public-school teaching position in Charleston, SC when she refused to deny her membership in the NAACP. She subsequently took a position at the Highlander Center in Tennessee, where she worked to develop “citizenship schools.” Clark trained African American teachers to go back to their own communities and convey voter registration procedures, local healthcare and employment opportunities, the ins and outs of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and how to access federal antipoverty benefits. The positions came with small salaries and they were behind the scenes and long-term. These qualities allowed women to get involved, stay involved and have a long-term impact in their communities and on the larger Civil Rights Movement. The interview excerpts are rich with descriptions of Clark’s upbringing; her short, married life; and her work experiences. This is an excellent piece for students of African American history; women’s history; the Civil Rights Movement; oral history; and southern studies.

This feature essay sheds light on two content strengths of Southern Cultures: oral history and the Civil Rights Movement. While Septima Clark is well known to Civil Rights scholars, she is under-represented in popular knowledge about the Movement. Hall and Walker, who interviewed Septima Clark for the Southern Oral History Program, provide an excellent introduction to Clark’s long-time civil rights work and to the compiled excerpts from the interviews that highlight key moments in her life. In the mid-1950s, Septima Clark was fired from her public-school teaching position in Charleston, SC when she refused to deny her membership in the NAACP. She subsequently took a position at the Highlander Center in Tennessee, where she worked to develop “citizenship schools.” Clark trained African American teachers to go back to their own communities and convey voter registration procedures, local healthcare and employment opportunities, the ins and outs of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and how to access federal antipoverty benefits. The positions came with small salaries and they were behind the scenes and long-term. These qualities allowed women to get involved, stay involved and have a long-term impact in their communities and on the larger Civil Rights Movement. The interview excerpts are rich with descriptions of Clark’s upbringing; her short, married life; and her work experiences. This is an excellent piece for students of African American history; women’s history; the Civil Rights Movement; oral history; and southern studies.

Septima Clark (right) and Rosa Parks (left) with Coretta Scott King, at the “1000 Women Honor Rosa Parks” event in Detroit, 1961, from the Septima Poinsette Clark Scrapbook, 1919–1983, courtesy of Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture, College of Charleston, Charleston, South Carolina.

A Short History of Redneck: The Fashioning of a Southern White Masculine Identity

by Patrick Huber, Vol. 1, No. 2 (Winter 1995)

Huber historicizes the word “redneck,” tracing its first usages back to late nineteenth-century Mississippi where whites and African Americans use the term to refer to poor whites. The etymology of “redneck” is hard to substantiate, but the most compelling theory suggests it derives from reference to white skin reddened by working in the sun. From the beginning, the word was used to identify color and class difference. Huber draws on the observations of travel writers such as William Cullen Bryant and Frederick Law Olmsted, to flesh this out: “non-slaving masses of southern white men…prized their racial identity because it distinguished them as free men and entitled them to political and civil rights” (152). Establishing the inferiority of African Americans, Huber argues, was critical to poor white southern identity. Intended to be pejorative, the term “redneck” has been reclaimed through the years and recast by those who embrace it to mean a “honest, hard-working workingman who identifies with traditional southern social and religious values” (157). Huber’s long view of the term incorporates Civil Rights, southern industrial, social, political and migration histories. It is a fascinating lens through which to consider race, class and masculinity in the South.

Huber historicizes the word “redneck,” tracing its first usages back to late nineteenth-century Mississippi where whites and African Americans use the term to refer to poor whites. The etymology of “redneck” is hard to substantiate, but the most compelling theory suggests it derives from reference to white skin reddened by working in the sun. From the beginning, the word was used to identify color and class difference. Huber draws on the observations of travel writers such as William Cullen Bryant and Frederick Law Olmsted, to flesh this out: “non-slaving masses of southern white men…prized their racial identity because it distinguished them as free men and entitled them to political and civil rights” (152). Establishing the inferiority of African Americans, Huber argues, was critical to poor white southern identity. Intended to be pejorative, the term “redneck” has been reclaimed through the years and recast by those who embrace it to mean a “honest, hard-working workingman who identifies with traditional southern social and religious values” (157). Huber’s long view of the term incorporates Civil Rights, southern industrial, social, political and migration histories. It is a fascinating lens through which to consider race, class and masculinity in the South.

Photo by Tammy Mercure.

“The First of Our Hundred Battle Monuments”: Civil War Battlefield Monuments Built by Active-Duty Soldiers During the Civil War

by Michael W. Panhorst, Vol. 20, No. 4 (Winter 2014)

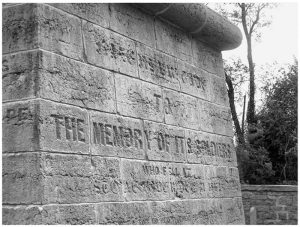

Panhorst draws the title for his essay from an article, published in the New York Times in in 1865, identifying monuments at Murfreesboro, Tennessee, and Manassas National Battlefield which were erected by committee and dedicated in 1865 as the “first of our hundred battle monuments.” His essay peels back these popular narratives of Civil War monuments erected by the United Daughters of the Confederacy or other institutional bodies, and invites readers to contemplate the monuments that soldiers themselves erected to honor their fallen comrades. “These,” Panhorst writes, “represent earliest attempts to mark Civil War battlefields for posterity” (23). Take, for example, the Bartow Monument at Manassas. The plain, round marble column honored Colonel Francis Bartow (1816 – 1861) who died while leading the 7th Georgia Voluntary Infantry in the first major battle of Manassas, Virginia in 1861. Panhorst features period writing by Melvin Dwinell who described the commemoration event and the memories that flooded him as he walked across the battlefield. He writes: Each soldier [as they wander the grounds] “imagines that he again hears the whiz of the canon ball—the zip-zip-zip-zip-zip-zip of the musketry charge, and the quick whist, whist of the rifle. He sees where this and that friend stood and where others fell” (26). This photo essay, with its deeply descriptive captions, highlights the need for commemoration, the act of marking ground made sacred by death and the work of ordinary people at crafting funerary art. Panhorst’s essay articulates well with other Southern Cultures essays about Civil War-era monuments (see the “Monuments and Memory” reading list on this website). An excellent resource for students of Civil War history; public memory; and commemoration.

Panhorst draws the title for his essay from an article, published in the New York Times in in 1865, identifying monuments at Murfreesboro, Tennessee, and Manassas National Battlefield which were erected by committee and dedicated in 1865 as the “first of our hundred battle monuments.” His essay peels back these popular narratives of Civil War monuments erected by the United Daughters of the Confederacy or other institutional bodies, and invites readers to contemplate the monuments that soldiers themselves erected to honor their fallen comrades. “These,” Panhorst writes, “represent earliest attempts to mark Civil War battlefields for posterity” (23). Take, for example, the Bartow Monument at Manassas. The plain, round marble column honored Colonel Francis Bartow (1816 – 1861) who died while leading the 7th Georgia Voluntary Infantry in the first major battle of Manassas, Virginia in 1861. Panhorst features period writing by Melvin Dwinell who described the commemoration event and the memories that flooded him as he walked across the battlefield. He writes: Each soldier [as they wander the grounds] “imagines that he again hears the whiz of the canon ball—the zip-zip-zip-zip-zip-zip of the musketry charge, and the quick whist, whist of the rifle. He sees where this and that friend stood and where others fell” (26). This photo essay, with its deeply descriptive captions, highlights the need for commemoration, the act of marking ground made sacred by death and the work of ordinary people at crafting funerary art. Panhorst’s essay articulates well with other Southern Cultures essays about Civil War-era monuments (see the “Monuments and Memory” reading list on this website). An excellent resource for students of Civil War history; public memory; and commemoration.

Hazen Brigade Monument, Stones River National Battlefield, Murfreesboro, Tennessee, built 1863–64, by Michael W. Panhorst.

Partisan Change in Southern State Legislatures

by Christopher A. Cooper and H. Gibbs Knotts, Vol. 20, No. 2 (Summer 2014)

Cooper and Knotts analyze the status of partisan competitiveness in southern state legislatures, looking at voting data from 1953 to 2013. They examine the well-publicized shift from Democratic to Republican political dominance in the South, starting in 1952, when, for the first time, white southerners voted overwhelmingly for a Republican candidate: Dwight Eisenhower. With the exception of Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, and Barack Obama, Republicans have carried the South in presidential elections ever since. And beginning in the 1970s, Republicans have also come to dominate congressional and gubernatorial elections in the region. The lesser known story is at the southern state legislature level, which, Cooper and Knotts maintain, has more impact on the day-to-day lives of southerners. They ask: Is there partisan competitiveness in state legislatures and what might the future hold for state legislative party competition in the South? They found a Republican trickle-down at the local level, but note that the trickle down has been slow and uneven. Louisiana and Mississippi, for example, which have large populations of African Americans, maintain partisan competitiveness in their legislatures, and at times have maintained dominant Democratic representation. Cooper and Knotts discuss redistricting and Nixon’s “southern strategy” (which garnered votes from proponents of states’ rights), which would be useful in generating discussion and further research about local voting practices and voting rights in the South. This essay would fit well in political science; southern studies and southern history courses.

Cooper and Knotts analyze the status of partisan competitiveness in southern state legislatures, looking at voting data from 1953 to 2013. They examine the well-publicized shift from Democratic to Republican political dominance in the South, starting in 1952, when, for the first time, white southerners voted overwhelmingly for a Republican candidate: Dwight Eisenhower. With the exception of Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, and Barack Obama, Republicans have carried the South in presidential elections ever since. And beginning in the 1970s, Republicans have also come to dominate congressional and gubernatorial elections in the region. The lesser known story is at the southern state legislature level, which, Cooper and Knotts maintain, has more impact on the day-to-day lives of southerners. They ask: Is there partisan competitiveness in state legislatures and what might the future hold for state legislative party competition in the South? They found a Republican trickle-down at the local level, but note that the trickle down has been slow and uneven. Louisiana and Mississippi, for example, which have large populations of African Americans, maintain partisan competitiveness in their legislatures, and at times have maintained dominant Democratic representation. Cooper and Knotts discuss redistricting and Nixon’s “southern strategy” (which garnered votes from proponents of states’ rights), which would be useful in generating discussion and further research about local voting practices and voting rights in the South. This essay would fit well in political science; southern studies and southern history courses.

President Lyndon Johnson, Ralph Abernathy, Martin Luther King Jr., and Rosa Parks at the signing of the Voting Rights Act on August 6, 1965. Photograph by Yoichi R. Okamoto, Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum.