“The Klan was trying to put a damper on the Lumbees. They were not going to come here and run the Lumbees away from their home.” —James Jones

On a frigid Saturday night in January 1958, Grand Dragon James “Catfish” Cole and fifty other members of the Ku Klux Klan gathered for a rally in a cornfield near Hayes Pond just outside of Maxton, a small town located in Robeson County in southeastern North Carolina. The armed Klansmen strung up a small light on wired a public address system. A large white banner emblazoned with a pole and wired a public address system. A large white banner emblazoned with the letters “KKK” in red hung menacingly nearby. Cole had organized the rally to protest the “mongrelization” of whites and Lumbee Indians in Robeson. But before the rally even began, several hundred Lumbees chased the Klansmen from the frozen cornfield. Stationed nearby, having feared the possibility of violence, local authorities and the State Highway patrol quickly moved in and restored peace. Despite numerous gunshots, there was only one minor injury, and the Lumbees took their spoils, including the KKK banner, to the nearby town of Pembroke to celebrate.

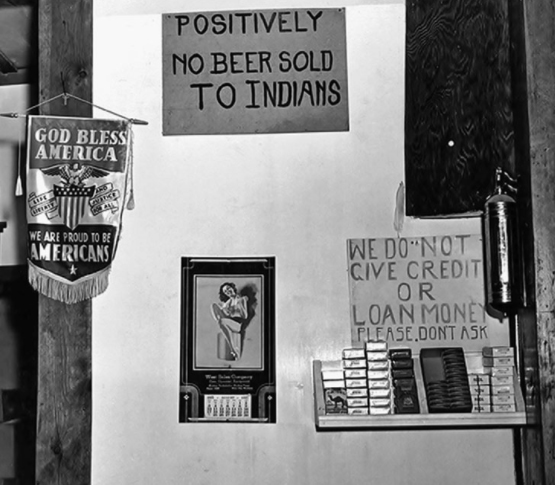

The “Maxton Riot,” as it came to be called, generated massive local and national media attention. People across the country read dramatic accounts in the Raleigh News and Observer, New York Times, Washington Post, Newsweek, Time, and other newspapers and periodicals describing how the Lumbee Indians, who were relatively unknown outside of southeastern North Carolina, had humiliated the Ku Klux Klan. In general, reporters, columnists, and editorialists praised the Lumbees for standing up to white racism and Klan terrorism, albeit by extralegal means. And yet, despite an overall positive tone, the news coverage of the Indian-Klan clash, especially outside of North Carolina, illustrated the media’s ignorance of Indian history and culture in the South. Reporters and pundits relied on racist stereotypes and simplistic Native American caricatures when commenting on the riot. In general, they employed Plains Indian imagery and iconography to characterize the event in terms of the vanishing noble savage bravely standing up to the invading white oppressor. Reporters wrote that angry “Redskins” yelling “war-whoops” “scalped” the “pale-face” in North Carolina. Eyewitness accounts contradicted these stories of “war-whoops,” but that did not matter, as journalists and columnists, making reference to Geronimo, Custer, and other nineteenth-century historical figures, wrote stories that read like pulp western novels or Hollywood screenplays. But of course the Lumbees of North Carolina, like other contemporary Indians in the South, did not conform to these stereotypes and generalizations of Native American culture. Although journalists and other commentators of the time most likely assumed that they were celebrating the Lumbee victory, their use of racist language and imagery reveals the struggle of many contemporary Indian peoples in the South to break free of mainstream misconceptions, stereotypes, and prejudices.1

The Lumbees of Robeson County

From the mid-1700s until the late 1800s, the Indians of Robeson County, ancestors of today’s Lumbees, lived in isolated settlements along the Lumber River. After the Civil War, however, North Carolina sought to divide all of its citizens into two racial categories, white and colored, spurred in part by the expansion of the state’s public school system during the emergence of the Jim Crow South. Although some of these Lumbee ancestors had English names and European physical features, such as blond hair and blue eyes, the Indians of Robeson County challenged this bi-racial system, insisting that they did not fit into either category. Consequently, in the late 1880s, the North Carolina General Assembly recognized the Robeson Indians as the Croatans, a reference to a Colonial-era Indian community, and helped finance Indian-only public schools. As a result, tri-racial segregation was legally codified in Robeson County by the turn of the twentieth century.

As it did for many other minority groups in the United States, World War II marked the beginning of a very important transitional era for the Robeson Native Americans. Hundreds of local Indians served alongside whites in integrated units during the war (unlike African Americans, who were still segregated in the military). After the war, Indian veterans returned to Robeson more worldly and ready to fight for social and political change. Veterans and other Indian leaders in the community also became increasingly unhappy they had no tribal name to represent their distinctive history and identity as an indigenous people. (In 1913, the N.C. General Assembly had officially labeled them the Cherokee Indians of Robeson County, making an inaccurate connection to the Eastern Band of Cherokees who lived on a reservation in the Great Smoky Mountains of western North Carolina.) Consequently, in the early 1950s, Reverend D. F. Lowry organized the Lumbee Brotherhood, adopting the name from the local river. Lowry and his supporters contended that since their people were most likely the descendants of a mixture of colonial-era indigenous tribes—a theory many scholars supported—they should adopt the name Lumbee after the river that had become a cultural hearth for the local community. In 1952, Robeson Native Americans overwhelmingly voted to adopt the new name, and the General Assembly subsequently changed their official designation in 1953 to the Lumbees.

Although the 1956 act recognized the existence of the Lumbees as an Indian community, it did not offer any of the accompanying rights and privileges.

Three years later, the U.S. Congress passed an act officially acknowledging the Lumbee Indians of Robeson County, during an era in federal Indian policy known as Termination, when the federal government was trying to sever ties with tribes, abolish reservations, and eliminate federal benefits, such as healthcare and housing. As a result, although the 1956 act recognized the existence of the Lumbees as an Indian community, it did not offer any of the accompanying rights and privileges that such recognition had brought other tribes. In fact, the legislation specifically prohibited the Lumbees from participating in any federal programs for Native Americans: “Nothing in this act shall make such Indian eligible for any services performed by the United States because of their status as Indians, and none of the statutes of the United States which affect Indians because of their status as Indians shall be applicable to the Lumbee Indians.”2

The Battle of Hayes Pond

In May 1954, the Supreme Court ruled in Brown vs. Board that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional, thus challenging the Jim Crow caste system that had dominated the South for more than half a century. Across the region, white southerners feared the prospect of sending their children to school with “coloreds,” which might lead to social interaction and, the worst fear of all, racial miscegenation. As a result of this hysteria, the Ku Klux Klan, which had thrived in the South during Reconstruction and again in the 1920s, began organizing and recruiting new members.

During the first half of the twentieth century, North Carolina had earned a debatable reputation as a moderate southern state on racial issues, and, to be sure, the state was not immune to Klan activity after the Brown v. Board decision. In 1956, Atlanta Imperial Wizard Eldon Edwards commissioned Reverend James W. “Catfish” Cole to oversee the reorganization of the KKK in the Carolinas. In January 1958, Cole and a few of his recruits went to Robeson County to protest several recent cases of social interaction between whites and Native Americans. (In the 1950s, Robeson’s population consisted of approximately 40,000 whites, 25,000 African Americans, and 30,000 Indians, most of whom were Lumbees. The three groups generally lived in separate communities and neighborhoods in the county.) On Monday, January 13, Cole and several Klansmen invited local reporter Bruce Roberts to accompany them while they “sent a message” about miscegenation to some local Lumbees. That night, the Klansmen burned a cross in the small community of St. Paul’s near the home of a Native American woman who was dating a white man. They also burned a cross near the Lumberton home of an Indian family that had recently moved into a mostly white neighborhood. Cole then told Roberts that he was planning a large Klan rally the following Saturday night somewhere in or near the town of Pembroke, the heart of the Lumbee community, where he would speak about the “mongrelization” of the races.3

The next day, Roberts wrote about the cross burnings and the planned rally in the Scottish Chief, a newspaper based in the small town of Maxton, and other local papers also picked up the story. As the news spread across the county, rumors circulated about the rally, to which Cole expected to draw hundreds, perhaps thousands, of Klan supporters. According to one such rumor, the sales of ammunition in Robeson gun stores skyrocketed on Tuesday, increasing the fear of a violent confrontation between the Klan and the Lumbees. Unable to find someone who would lease him land in Pembroke, Cole rented a small cornfield from a white farmer who lived near Hayes Pond just outside of the town of Maxton, about ten miles or so from Pembroke. Cole and other Klansmen then drove a truck around Robeson County using a loudspeaker to publicize the rally. Angered by the threats from the Klansmen, many Lumbees prepared to confront these invaders. “When they came through town saying those things over a loudspeaker, that was it,” recalled Lumbee Clyde Chavis. “It’s like this blew the lid off all of it.” By Saturday afternoon, many Robeson residents fully anticipated violence as word spread that four groups planned to converge that night near Hayes Pond: Klansmen, Lumbees, county and state authorities, and local and state media.4

The rally was scheduled to start at 8:30 p.m. Around 7:00, the first cars turned off of the small road that led around Hayes Pond and parked near the middle of the barren cornfield. About ten Klansmen got out of the cars, one wearing Klan robes, another dressed like a cowboy, most wrapped in heavy winter jackets for the expected low that night in the mid-20s, and all carrying guns. At first, the Klansmen were confident, even cocky. Cole had told his followers to expect at least five hundred other Klansmen that night, which would have been a strong show of force.

“You’d better be careful,” one of them said to a reporter from the News and Observer “We’d hate to shoot the wrong man.”5

The Klansmen set up a light pole and a public address system, both of which were plugged into a small portable generator, and hung a three by five foot white banner stitched with the letters “KKK.”6

Four groups planned to converge that night near Hayes Pond: Klansmen, Lumbees, county and state authorities, and local and state media.

Over the next hour or so, traffic adjacent to the field rapidly increased. Some automobiles parked near the light pole, where Klan members exited their vehicles to congregate in the center of the field. But the majority of cars, each carrying three to six Lumbees, parked alongside the road. Most of the Lumbees present that night were men, but a few women also went, including Pauline Locklear. “It was something to see,” she recalled. “I guess I was a rebel at the time.” The drivers and passengers waited inside with the engines running to keep warm. By 8:00, the number of cars on the road greatly outnumbered those on the field. Initially brash, the Klansmen grew worried about the increasing ratio of Indians to whites. Robeson County Sheriff Malcolm McLeod was also there, standing with a couple of his deputies near James Cole just outside of the main circle of Klansmen. A dozen State Highway Patrol officers, who would only move in if trouble started, were stationed out of sight a mile or so down the road.7

In the meantime, as Cole rehearsed his speech on the evils of integration, the PA system played Christian hymns, including “Kneel at the Cross.” Around 8:15, the Lumbees began to get out of their cars and move across the dark frozen field toward the Klansmen. There were only about fifty Knights present, far fewer than Cole had promised, but there were three to four hundred angry Indians slowly walking toward them. Most of the Lumbees wore heavy winter coats, leather jackets, and fedora hats. (Needless to say, none wore buckskins, feather headdresses, or moccasins.) The Lumbees started taunting the Klansmen, shouting “We want Cole” and “Goddamn the KKK,” among other insults. The Klan members responded with racial epithets, calling Lumbees “half-niggers,” and Sheriff McLeod pulled Cole aside. “Well, you know how it is,” he told Cole. “I can’t control the crowd with the few men I’ve got. I’m not telling you not to hold a meeting, but you see how it is.”8

It could have been a lot worse. No one was hurt. It turned out to be a beautiful situation, and the Klan moved on.

James Jones

It was unreal. It was something that you always remember. I am still puzzled that no one got killed.

Pauline Locklear

Although I didn’t do much, I just feel good about what happened. We didn’t back down. We stood up and took care of business.

Ned Sampson

Still, Cole refused to cancel the rally. As the minutes ticked by, hundreds of Lumbees inched closer and closer to the circle of Klansmen. By 8:25, the two groups were close enough to see each other’s faces in the faint glow of the light pole. Rifles clicked; guns were locked and loaded. Just before 8:30, two young Indian men rushed forward, grabbed the light pole, shattered the light, and shut off the PA. Darkness and a momentary silence fell upon the field before rifle shots and shotgun blasts filled the freezing air. Photographers’ flashbulbs popped like streaks of lightning, creating an odd strobe-light effect. Knowing that they were heavily outgunned, the Klansmen, including Cole, quickly retreated toward the road and trees surrounding the field, some even abandoning their wives and children, who had been trying to keep warm by sitting inside of their cars in the middle of the field. The gunshots continued, and two tear gas bombs, apparently fired by Robeson deputies, erupted in the middle of the chaos, covering the field in a smoky haze that irritated eyes and noses.

Within minutes, Captain Raymond Williams of the N.C. State Highway Patrol led his men, some armed with sub-machine guns, onto the field. Together, Williams and McLeod managed to restore order, and by 9:00, the field was once again calm and quiet—a chilly breeze had even blown away the tear gas. Miraculously, no one was seriously hurt. The Lumbees intentionally had fired upward in order to scare, rather than kill, their antagonists. “It was unreal,” Pauline Locklear recalled. “I am still puzzled that no one got killed.” McLeod and Williams confiscated two carloads of rifles and shotguns from both Indians and Klansmen. There was only one arrest at the scene—McLeod charged Klansman James G. Martin, a tobacco plant worker from Draper, with public intoxication and carrying a concealed weapon.9

The Lumbee victory party began soon after the firing stopped. Several Indians talked with reporters and posed for photographers. The party continued late into the night and early into Sunday morning. The Lumbees took the PA system back to Pembroke, where they celebrated outside of the police station by hanging and burning an effigy of Cole. Two Lumbees, Charlie Warriax and Simeon Oxendine, the son of the mayor of Pembroke and a veteran of World War II, also took the captured KKK banner and drove 140 miles to Charlotte, where they entered the offices of the Charlotte Observer around midnight to tell their story. “This Ku Klux banner is mine,” Oxendine told a reporter. “And I’m going to walk into the lobby of the Charlotte Hotel wearing it like a scarf.”10 A photograph of Warriax and Oxendine carrying the banner around their shoulders became the dominant image and symbol of the Lumbees’ victory over the Klan that night in Maxton, a picture that ran in numerous newspapers across the country.

“This Ku Klux banner is mine,” Oxendine told a reporter. “And I’m going to walk into the lobby of the Charlotte Hotel wearing it like a scarf.”

Simeon Oxendine

A week later, on Monday, January 20, Sheriff McLeod announced that he would seek an arrest warrant for Cole and others. The next day, a Grand Jury in Robeson County charged James Cole, James Martin, and others unknown to the state for inciting a riot in Maxton. On Wednesday, Judge Lacy Maynor, a Lumbee, fined Martin sixty dollars and gave him a sixty-day suspended sentence for public drunkenness and carrying a concealed weapon. In the meantime, Cole had fled to his home in South Carolina, where he posted bond and announced that he was going to fight extradition. On January 27, Cole, obviously humiliated by the whole affair, announced plans for another Klan rally in Robeson County. The next meeting, Cole claimed, would be very different. “It will be the greatest rally the Klan has had,” Cole said. “I expect there will be more than 5,000 Klansmen there and probably more. Klansmen all over the South are pretty upset.”11

But the rally never occurred, and Cole reluctantly returned to Robeson County for his trial. Cole claimed in his defense that the Klan had legally rented the property and had a right to hold a rally. He blamed the Lumbees and the Robeson sheriff, who, in his opinion, had not offered adequate protection, for the violence. The prosecution, however, argued that Cole and the Klan had caused the riot. First, the Klan had started the whole affair by burning crosses and agitating the Lumbees using inflammatory rhetoric. Second, the Klan had advertised the Saturday rally as a public event, not a private meeting. And finally, the Klan, based on statements made by James Martin after his arrest, had encouraged attendees to bring weapons to this public rally. In March, a tri-racial Robeson County jury found both Cole and Martin guilty of inciting a riot, and Judge Clawson Williams sentenced Cole to eighteen to twenty months in prison.12

To read this piece in full, access it via Project Muse or purchase Southern Cultures, Vol. 14, No. 4: First Peoples, in our online store.

Christopher Arris Oakley is and an associate professor and the Department of History chair at East Carolina University, where he specializes in North Carolina Native American history. His book, Keeping the Circle: American Indian Identity in Eastern North Carolina, 1885–2004, presents an overview of the modern history and identity of the Native peoples in twentieth-century North Carolina.NOTES

1. There is some controversy whether “riot,” which is a racially loaded term, is the right word for this incident. I have used it here because most media outlets at that time referred to it as such.

2. Quote in Gerald Sider, Living Indian Histories: Lumbee and Tuscarora People in North Carolina (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 129; Adolph L. Dial, The Lumbee (New York: Chelsea House, 1993), 90-95; Adolph L. Dial and David K. Eliades, The Only Land I Know: A History of the Lumbee Indians (San Francisco, CA: The Indian Historian Press, 1975), 156-159; Karen I. Blu, The Lumbee Problem: The Making of an American Indian People (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 70.

3. Dial, The Lumbee, 95-99; Dial and Eliades, The Only Land I Know, 159; Charles Craven, “The Robeson County Indian Uprising Against the KKK,” South Atlantic Quarterly 57 (1958): 43-40; William H. Chafe, Civilities and Civil Rights: Greensboro, North Carolina, and the Black Struggle for Freedom (Oxford University Press, 1981).

4. Quote from The Fayetteville Observer, January 18, 2008; “Maxton Board, Citizens Ask Boycott of Klan Meet,” The Scottish Chief, January 17, 1958, 1; “Klan Cross Burnings Anger Robeson Citizens,” The Scottish Chief, January 17, 1958, 1.

5. “One Klansman to Face Charges; Minister Slated For Indictment,” The News and Observer, January 20, 1958, 1, 3.

6. Craven, “Robeson County Indian Uprising,” 43-40; Dial, The Lumbee; Lew Barton, The Most Ironic Story in American History: An Authoritative, Documented History of the Lumbee Indians of North Carolina (Charlotte, NC: Associated Printing Corporation, 1967), 98; Dial and Eliades, The Only Land I Know, 159-160; Sider, Living Indian Histories, 101.

7. Quote in The Fayetteville Observer, January 18, 2008; Craven, “Robeson County Indian Uprising,” 43-40; Dial, The Lumbee, 90-95; Dial and Eliades, The Only Land I Know, 156-159.

8. Craven, “Robeson County Indian Uprising,” 439.

9. Quote in “Four Who Were There,” The Fayetteville Observer, January 18, 2008; Barton, The Most Ironic Story, 98; Dial, The Lumbee, 95-99; Dial and Eliades, The Only Land I Know, 159-160; Penkins, “Gathering Broken Up,” 1; Julian Morrison, “Whooping Lumbees in Wild Uproar Use Gas, Guns,” The Greensboro Daily News, January 19, 1958, 1; Craven, “Robeson County Indian Uprising,” 43-40.

10. Quote in Robert A. Willis, “Proud Lumbee Holds Klan Flag As Trophy,” The Greensboro Daily News, January 20, 1958, 1; “‘This Banner is Mine,’” The News and Observer, January 20, 1958, 3.

11. “Cole Plans Another Rally With Indians Outnumbered,” The Robesonian, January 27, 1958, 1.

12. Letter from John A. Mason, Legal Assistant to Governor George B. Timmerman, Jr., to James Cole dated January 30, 1958, Box 40.1.a, James William Cole Papers, Collection No. 40, East Carolina Manuscript Collection, J. Y. Joyner Library, East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina (hereafter cited as James William Cole Papers); Letter from James Garland Martin to James W. Cole dated July 29, 1957, Box 40.1.a, James William Cole Papers; “Jury Charges Klan Leader,” 1; “Trial of Klansmen Set For Wednesday,” The Robesonian, January 23, 1958, 1; “King Kat-fish Kole Kries Against Robeson Justice,” The Robesonian, January 28, 1958, 1.