This article first appeared in vol. 16, no. 2 (Summer 2010) and is excerpted here. To access the full article, visit Project MUSE.

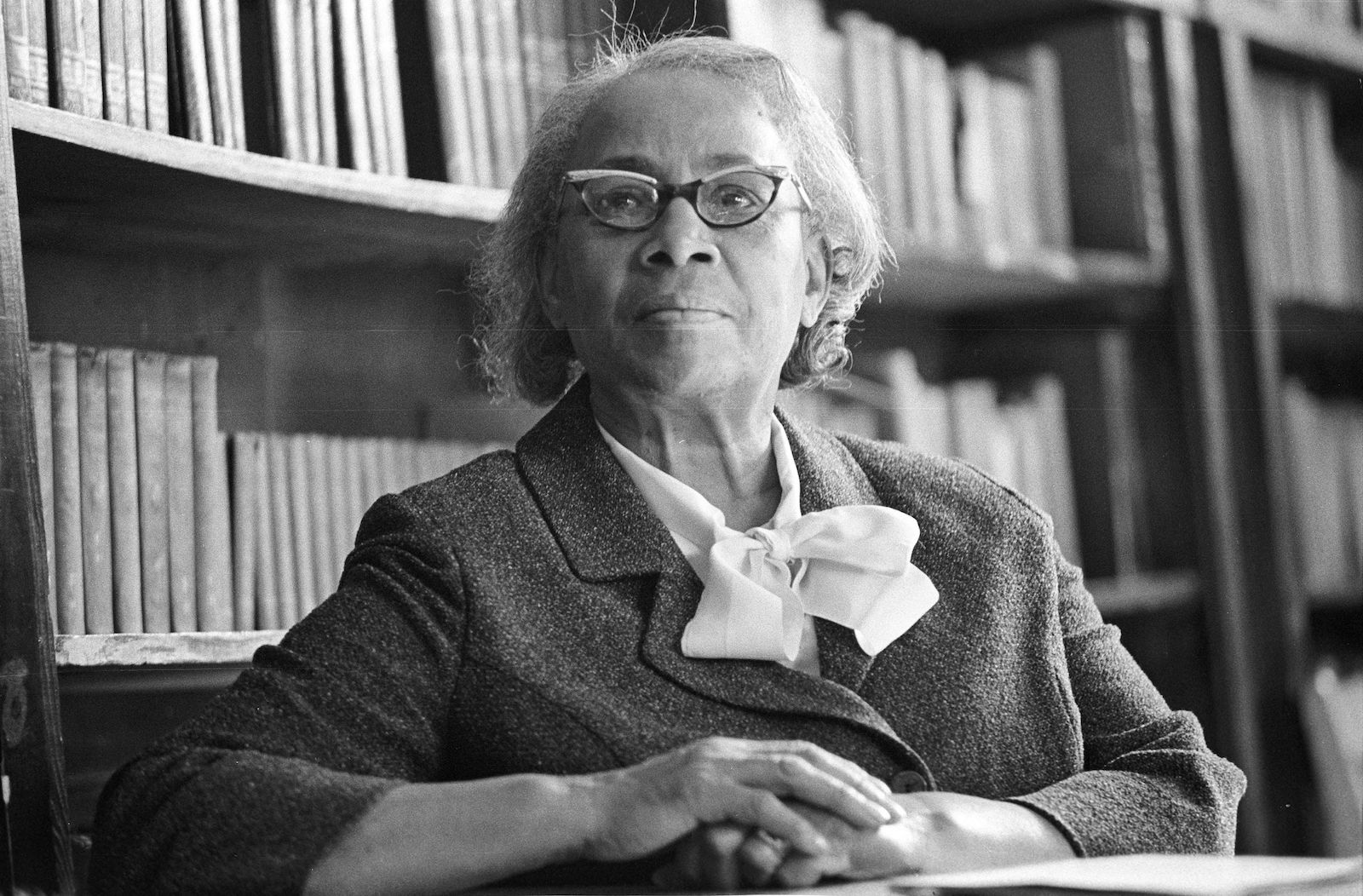

Septima Poinsette Clark is a name that should be as familiar to us as Rosa Parks. Both women contributed significantly to the African American freedom struggle, and striking similarities exist in their stories. Each had a long record of participation in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP); each challenged segregation and was arrested as a result; and each worked with Martin Luther King. In fact, four months before Rosa Parks’s infamous arrest, she attended a workshop at the Highlander Folk School, an interracial adult education center in Monteagle, Tennessee, where activists gathered to devise solutions for problems in their communities and where Clark served as Director of Education.

Yet, unlike Parks, Clark never captured the national media’s attention for her Civil Rights activism. This certainly offers one explanation for her relative obscurity. Another lies in Clark’s age. Born on May 3, 1898, in Charleston, South Carolina, she was nearly sixty years old when the classic phase of the Civil Rights Movement began, which has eclipsed her role in narratives that focus on youth, such as those in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Finally, there is the nature of Clark’s work in the Movement: using education to empower grassroots people, particularly African American women, so they might become leading citizens in their communities.

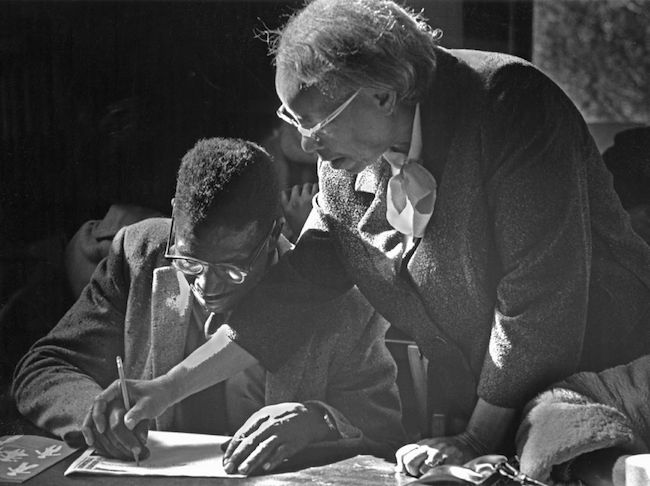

Septima Clark spent forty years as a public school teacher and civic organizer in the Jim Crow South, teaching citizenship by helping people to help themselves. In the mid-1950s, she drew on her experiences to develop a citizenship education program that directly linked self-help to politics by teaching African Americans to read and write so they could pass the literacy tests required by southern states to register to vote. Beyond adding their names to the voting rolls, however, students also discovered how to transform their relationship to the wider society. Teachers relied on charts, for example, to explain the structure of local and state government as they led discussions of what citizens do; they taught people how to create a household budget, balance a check book, and apply for Social Security benefits. As students learned of citizenship responsibilities that included establishing local voting leagues, paying taxes, and lobbying for improved municipal services, they came to understand citizenship as more than an individual legal right they possessed. Indeed, African American adults who passed through the classes acquired both the knowledge and the skills to apply their citizenship on behalf of the broader community.

In editing these oral history interviews, we have chosen excerpts that highlight telling moments in Septima Clark’s personal development and that underscore her activist approaches. Foremost, conditions in the rural and urban segregated schools in which Clark taught sensitized her to the need to advocate on behalf of African American children and to expand professional options for African American women. In both the World War I and World War II eras, she enlisted in NAACP campaigns that pursued these goals. The personal tragedies that followed her earliest political involvement yielded setbacks, but relocating to Columbia, South Carolina, in the interwar years helped Clark to overcome them as she learned how to function within a larger network of African American women. The necessity of her seeking employment in the summertime reminds us of teachers’ precarious financial situations as well as her motivation for supporting salary equalization. In South Carolina, federal judge J. Waties Waring ruled in favor of African American teachers in these suits; he also opened the Democratic Primary to African American Carolinian voters in 1948. Waring’s decisions on behalf of African American plaintiffs, and the circumstances of his divorce and then second marriage, made him an iconoclast in Charleston. Befriending the Warings in 1950 and joining their call for immediate integration, Septima Clark took an uncompromising, and unpopular, stand. When the all-white Charleston school board fired her for refusing to deny her membership in the NAACP six years later, she went to work full-time at Highlander. Disappointment in generating support for her previous efforts had taught Septima Clark that the people who would accept the risks of activism needed to build their confidence at the outset, which is why she insisted on a literacy-based citizenship pedagogy. The first Citizenship School opened on Johns Island, South Carolina, in January 1957. The schools spread first in the South Carolina Lowcountry, then to Georgia and Alabama. In 1961, Clark migrated with the program to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), where she stayed until her retirement in 1970.

At both Highlander and SCLC, Septima Clark and her colleagues prepared a network of grassroots teachers in week-long training sessions. Here, prospective teachers from across the South learned how to recruit students, gauge their educational levels, and develop lesson plans. Would-be teachers also had to know the location and hours of their voter registration office and what healthcare and employment opportunities were available in their communities. Over the years, SCLC staff adapted their training curriculum to new developments in the Movement. Soon after President Lyndon Johnson signed the 1964 Civil Rights Act, for example, Citizenship School teachers incorporated it into their reading lessons, along with instructions for accessing the federal benefits that accompanied the antipoverty legislation Johnson signed that same year. In between the training sessions, which occurred once a month, Clark went into the field to assist her teachers, to find more, and to support SCLC’s campaigns.

From the beginning, the Citizenship Schools served as more than voter registration classes. Every teacher came from the community in which she taught and began class by asking her neighbors what they wanted to learn. Thus, they relied on a curriculum that was both specific, in terms of preparing students to register, and flexible enough to meet local people’s other educational desires. As students gained practical, political, and economic literacy, the schools became all-African American sites of mobilization and allowed people to define the Movement in their town in terms of how they applied their new knowledge. Graduates put what they had learned into practice by influencing others to register and vote, by assuming leading and supportive roles in local Civil Rights campaigns, and by joining existing organizations or establishing new ones to tackle community welfare needs.

Women predominated as both teachers and students in the Citizenship Schools. Although education had long been perceived as “women’s work,” Clark’s program appealed to women for several additional reasons. First, when compared to losing one’s job, facing eviction from a white landlord, or risking one’s life by participating in direct action campaigns, teaching adults to read and write appeared a relatively safe entry point into the Movement. The small stipend teachers received for their endeavors, funded by grants from private foundations, also helped women supplement their family incomes. Perhaps most significantly, Clark emphasized everyday experience in the political preparation process. Training sessions and teaching classes afforded grassroots African American women the opportunity to evaluate the local problems they deemed most important while the Movement itself provided a vehicle for addressing them. The Citizenship Schools also fostered women’s self-confidence in their leadership; as they turned their attention to solving community problems, they helped to expand the Movement’s goals beyond voter registration. Moreover, their advocacy continued into the following decades. Simply put, their Civil Rights Movement did not “end”; rather, it became a way of life.

Simply put, their Civil Rights Movement did not ‘end’; rather, it became a way of life.

Reconsidering Clark’s life challenges many of our ideas about the Civil Rights Movement, including its chronology and the infrastructure upon which it depended. Due to her own lived experience, Clark understood that change was a long-haul process and that effective grassroots activism remained inseparable from on-going grassroots education. But she also had to navigate the Movement’s internal divisions based on class and gender. As a teacher and civic activist, Clark had spent most of her life working within woman-centered networks. Undoubtedly, this informed her recognition of women’s crucial roles in realizing Civil Rights goals as well as the reasons why they did not receive recognition for their contributions. Clark’s life intersected with many other well-known actors. Yet from her perspective, developing a cadre of local leaders was the measure of the Movement’s success. Between 1957 and 1970, more than 5,000 people received training to become Citizenship School teachers; collectively they taught more than 25,000 people. We will never know all of their names or the full extent of their accomplishments. What we do know is that Septima Clark’s lessons made a difference.

Septima Clark in Her Own Words

Her Education and First Political Involvement

When we were children, the one thing [my father] wanted was for us to have an education. This was the only thing that I know he would whip you for: if you didn’t want to go to school. There were times we didn’t want to go. I cried one morning I didn’t want to go to that school, and he whipped me with a strap and then took me down there.

I went to the public school in the fourth grade and stayed there till the sixth grade. At Avery, I went into the ninth grade and started my high school work. Avery was a [private] school [in Charleston] that was founded by the missionary women out of Massachusetts. They came down right after the Civil War and started the school for blacks.

[To pay my tuition at Avery] I took care of a lady’s two children that lived across the street from me. She was a dressmaker, and I took care of her children in the mornings and in the afternoons. The only way I went to school was because she paid the dollar and a half a month for me to go. So there weren’t too many people of my status going to Avery. They were mostly the doctors’ daughters. I really enjoyed my schooling at Avery. It was great to me. When I was on that gallery at public school, if you fell asleep they whipped you. [I] finished Avery in 1916. Avery at that time gave something called a licentiate of instruction, which is equal to two years of college today, and I got that. And then I went over on John’s Island in 1916 at the age of eighteen and started teaching.

In all the public schools [in Charleston], you know, we had white teachers teaching black children. In 1919, we went door-to-door to ask people if they wanted black teachers to teach their children. That was my first real political thing. Because the lawmakers said that only the mulattoes wanted these jobs, and they didn’t think that the domestic workers and the chauffeurs and the garbage people and the longshoremen wanted black teachers. So we had to do a door-to-door thing to get black teachers to teach their children. And in 1920 we got them. Oh, that thing had been coming a long time, but we hadn’t gotten to the place where we felt as if we could get the signatures before. I took my students along with me, and we got these signatures. Some would be across the street, and then I’d do it on the other side, and that’s how we did it.

Activism in Columbia, South Carolina, 1929–1947

It was the ’29-’30 year. I went to Columbia for the first time. I joined the NAACP. There must have been around eight hundred or more [members]. It was a big chapter. We met at Benedict College. I never did know of any white members. Dr. Robert Mance was president.

The equalization of teachers’ salaries—we worked for that. I think it was [1946] before we got it finished. I was able to get some affidavits from both white and black teachers about salaries and show the discrepancies.

Other than the teachers’ salaries, the biggest thing I did in Columbia was to go to school and get my bachelor’s degree. Segregation caused us to have double sessions. I taught from twelve o’clock in the day till five in the afternoon. In the mornings I could take two or three classes at one college, because I was in a college town, and at night I could take two or three more. This was how I was able to take my degree, taking six hours, and finally finished in 1942.

The summer of ’42 I went to Maine and worked waiting tables in a camp, Camp Green Shadows in Harrison, Maine. The [teaching] salary was so little, and I had a child to support, too. My husband was dead. I wanted to buy a house for my parents, and so I went up there and worked for the summer. And it cleared my money that I made in the winter.

The 1961 transfer of the Citizenship Schools to the SCLC

I was arrested in 1959, and padlocks were put on the doors at Highlander Folk School. When they arrested me, Myles [Horton, who founded Highlander in 1932] knew that next thing was they were going to close down the school, because we were working against the laws of the state of Tennessee; they still had segregation. So he had talked with Dr. [Martin Luther] King. Dr. King said he would like to have me come, that he would like to have the program that we started at Highlander come to Atlanta. I was sent to Atlanta to carry out the citizenship education program. In transferring the program, Dorothy Cotton [educational consultant for SCLC] and Andy Young [King’s administrative assistant at SCLC and later Executive Director of SCLC] were placed in that grant along with me.

When Dr. King took it over, we worked at a center in Liberty County, Georgia. The very first month, we travelled through Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. We did encounter difficulty, because there were too many people in the South who were afraid of Highlander Folk School. Blacks and whites were able to live together and work together at Highlander. The people of the South had a feeling—that came out in the McCarthy era—that if blacks and whites mixed, they’re bound to be Communists. So that gave us a good bit of trouble in the communities.

[The Citizenship Education Program was] designed to eliminate illiteracy and get people ready to register and vote. We were looking for those who could read well aloud and who could write legibly to come and be trained and go back into their communities and work with the illiterates. We didn’t need anyone with a high school education, nor did we need anyone with a college education. We just wanted to have a community person, so that the illiterates would feel comfortable. They had to also promise that they would go back to the community and open up a school, and they were supposed to teach two nights a week, two hours each night. We had all of the books mimeographed that we wanted them to use in teaching. We used the election laws of that particular state to teach the reading. Each state had to have its own particular reading, because each state had different requirements for the election laws. And in each state we had to do different things. We used the amount of fertilizer and the amount of seeds to teach the arithmetic, how much they would pay for it and the like. We did some political work by having them find out about the kind of government that they had in their particular community. And these were the things that we taught them [to do] when they went back home.

The Marshall Field Foundation gave us $250,000 for the Citizenship Schools. We had to bring the people from eastern Texas and from all the way up the northern part of Virginia into Liberty County, Georgia, to work, to study for a week. We had to pay the board while they were there, and they had recreation while they were there. They put out a certain amount of money to give them to travel.

Her role in the Civil Rights Movement

We had the [teacher training workshops] once or twice a month. In between the workshops I went to various places to work with the people.

I went down to Albany [Georgia, in the summer of 1962], and I stood at the courthouse door, I guess for eight or ten days, from morning until late afternoon, telling the black people as they came up, “Go ahead and register.”

The white man would say, “You can’t vote in this election. It’s no use for you to register.”

I would say to them, “Registration is permanent in Georgia, so you go ahead and register now. And if you can’t vote in this election, you can vote later on.” I stayed by that door in Albany from nine o’clock in the morning when the registration books opened till five o’clock in the afternoon, just leaving for lunch.

We had the marches in Birmingham [in the spring of 1963] and were able to get the Civil Rights bill—in 1964 —and then when we did the Selma-to-Montgomery march in March of ’65. In August of ’65 we got the Voting Rights bill. I really felt that that was a great turning point. And the reason why I say that: I went into Selma, Alabama, and worked from May ’65 to August getting people to learn how to write their names. I had opposition with five black preachers, who didn’t want me to teach them to write their names in cursive writing. All right, Dr. King sent us in there to get this done. We went in together, all of [the others] left me; they couldn’t take the foolishness from those preachers. I stayed, and I got the teachers of Selma to work in their kitchens and in various offices to teach these people to write. When they learned to write their names, they had to go uptown to the courthouse and demonstrate that they could write their name. Then they received a number. In August of that year we had 7,002 persons ready to write their names, and we got that many voters.

In 1966, I went into Camden, Alabama, and down into another little town down there, and it was election time. One of the fellows we were teaching went up to the bank in Camden, and the man took the pen and said, “I’ll make the X.”

He said, “You don’t have to make the X for me, because I can write my own name.”

He says, “My God, them n—–s done learned to write their names.”

Violence and Nonviolence

We had lots of opposition. In Natchez, Mississippi, I went to recruit and to establish schools. While I was down there, one night in a Baptist church the Ku Klux Klan surrounded us. The Deacons for Defense from Louisiana [a Civil Rights organization devoted to armed self-defense] had come over that night for the program. That was in the early part of ’65. Anyway, at that place we were really having a lot of trouble, but the Chief of Police came out and asked the Ku Klux Klan to go back into their homes and asked the colored people would they go to their homes. The reason why I think the klansmen surrounded us that night at the church was because that day we had carried a large number of people up to the courthouse to register to vote. While there, one of the white men of the White Citizens’ Council [an anti-integrationist group] kicked a white boy who was working along with me. When he did that, I called Washington to get the Attorney General to see if we could peacefully work at that courthouse. That’s where we had to register. In a few minutes, he called the Chief of Police of Natchez, and when he did that we got protection at the registration office.

Thinking about Dr. King, I had the experience of knowing that he was really nonviolent. In Birmingham at Gaston’s Motel in 1963, before those little girls were killed [in the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church on September 15], we were having a workshop down there. Numbers of men were talking, and Dr. King was introducing a fellow from California. A white fellow came up with his collar wide open, and we wondered if this was the man he was introducing. When he got up there he hit Dr. King in the face twice. Dr. King dropped his hands like that of a newborn baby. I was sitting to the front, and I said, “Don’t hit him. Don’t hit him.” So he dropped his hands, and the other men jumped up, old men eighty years of age and all. They had sticks; they were about to hit him. Dr. King said, “Don’t touch him. Don’t touch him. We have to pray for him.” At the same time we were working with young people, telling them if they couldn’t march without being violent, then we’d have to take them off the line.

I’ve never been a person to fight—but Fannie Lou Hamer [grassroots leader in Mississippi and one-time Citizenship School teacher] was being tried in Oxford, Mississippi, in 1964 , because she and some others went into the front part of a bus station in Indianola. They threw them all in jail, and they beat her terribly. There were five of our people. Annelle Ponder [SCLC recruiter for Citizenship School teachers in Mississippi], they beat her eyes almost out. I went into Oxford, because these same people who had been beaten, their trial came up. When I heard those [white] men testifying at that trial, I wished that a chandelier would drop on their heads and kill them. My mind wasn’t nonviolent. And I don’t think that I’ve gotten to the place today where my mind is quite nonviolent, because I still have feelings at times that I’d like to do something violently to stop people.

Young people and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee

When I worked with those young people who came down [in the 1960s], the college students, I would say to them, “Don’t go and cash the check for this woman. Let her do it; you can go with her, give her that much courage. But make her cash her check and do her own talking so that she can have the feeling that she can. She’s been trading at the A & P all this time; let her take her check to the A & P store.”

I felt that they were young people who didn’t get the facts and just went right off the top of their hats. Now that’s not all of them. They always wanted things done quickly, though. You know, they don’t have time to wait. Stokely Carmichael [SNCC organizer, and later chair of SNCC]—he went into a community with his thinking up high, and theirs was still down low, and so he couldn’t get anything done. You can’t get it done unless you get the people sensitized to the fact of what you would like to see happen. When I was down in Selma, Alabama, some women came over [from Lowndes County] to tell me that Stokely Carmichael was really overstepping his bounds, and she was afraid that all of them would be killed. I went over there to speak to that whole group.

With the Black Power boys, I was in Atlanta. I invited Stokely Carmichael to come; I wanted to talk to him. He thought Dr. King was too soft. That’s why I was inviting him to lunch. I wanted to see if we could sit down and work [it] out. He did come when I promised to give him dinner that day, and he brought six other boys. I brought them to Pascal’s and fed them all. When I asked him about his behavior, you know, with the Black Power bit, he just laughed.

I said, “Can’t you find something else to tell these young men to do other than to have them going around with their fists clenched, saying ‘Black Power’ and intimidating black people up and down Auburn Avenue?”

He was tickled to death about it. But since that time, he’s changed in the way he handled those things.

I feel that the boys were a little bit too radical. I think we needed just such people, but I think we needed to try to find out more about the facts. I think they need to listen to us, and we need to listen to them. That’s the way I feel about SNCC.

Some of the white girls fell in love with the boys, and they couldn’t do anything else about it. You know, [SCLC] had a program called “Scope,” and we had large numbers of white girls coming in. They were very hard [workers], but they were hardheaded, too. I tried to get them to stay [away] from uptown at nights, and naturally they would get into trouble. They’d arrest them if they saw them up there with those black boys. In Mississippi, I had lots of complaints from the black girls about the white girls coming in. They claimed that they took over the black boys completely, and they weren’t able to get anything done.

Women in the Civil Rights Movement

[When Andrew Young was executive director of SCLC] we branched out to something like fifteen different women [working in the main office]. The organization grew. I think it happened because of the team of workers. There were, at one time, 195 classes going on in the eleven Deep South states, which called for a number of workers. Those women had to mimeograph books for each state. They had to get material out. They had to order material from Texas. They had to keep track of the students and all of the things that we needed for the students. So it branched out into a big thing.

I remember we worked on John’s Island for three years, and all the women would do would be serving the tables. One Sunday a woman said, “Mr. Esau [Jenkins—a community leader instrumental in establishing the first Citizenship School], yes, we want such-and-such a thing,” talking about typing classes for the children.

He said, “Just sit down there and say nothing.”

She said, “Yes, we want a typing class, and we want a typing teacher, too!”

And I put that down as a benchmark, for this woman [to] stand up and say something. They didn’t speak. They sat down there. They thought these things, but they swallowed them.

[Women] never let the men know what you feel or how you think. We had a workshop down at Fayette County [Tennessee], and those women that night [were in] that bedroom, and they just talked about how they could fool their husbands about their feelings, you know. Wouldn’t let them know how they were thinking. Men aren’t accustomed to women standing up and talking to them, and it’s hard for them to take it.

[Women exerted leadership locally] very little at first. But as the Civil Rights went into its tenth year or so, women started speaking out. In the beginning they were listeners only. They did many things to help in the Civil Rights Movement, but you’ll never see it put down anywhere in any of the reports. I don’t know why it is, but they don’t give the women any of the glory at all.

It’s just starting to come now.

This article first appeared in vol. 16, no. 2 (Summer 2010) and is excerpted here. To access the full article, visit Project MUSE.