“Let’s go around the room and say where we’re from.” It was my first day in a class called “Experiencing Appalachia” during my first year of college.

“Raleigh,” someone said.

“Just outside of Charlotte,” said another.

“High Point.”

The professor continually nodded as the circle made its way to me.

“Haywood County,” I said.

Her eyebrows raised in respect.

My home was only about a hundred winding miles from the classroom in which I was sitting, but “Haywood County” suddenly became more than a place to me. It was a marker of identity.

On day one of class, I learned that the region’s boundaries have been constantly contested. I was told that migratory patterns explain some of the dialects of the mountains. And I came to understand that I was Appalachian.

I knew that I was a mountain girl. My family had been in Haywood County for generations and one branch of my family tree started or stopped—depending on your perspective—when the Cherokee were marched through. But I had to take a class called “Experiencing Appalachia” to even know that I was Appalachian.

I ate more tempeh than I did fatback, and I loved Ani DiFranco and Doc Watson equally.

To “experience” the region, we studied Foxfire magazines like those that had lined the bookshelves in my childhood living room. We practiced churning butter. We read about quilting. Some of this resonated with me because it was familiar. My Granny painstakingly taught me to quilt one summer, which mostly meant that I spent time watching her pull out all of my sloppy handwork. My Granny and Pa, who lived next door, canned homegrown tomatoes and green beans. I knew the difference between half-runners and blue lakes, and know of no sound more satisfying than the pop of lids sealing on the kitchen counter in the late afternoon. But there were plenty of Appalachian traditions that I did not know. And there was nothing markedly Appalachian that we did because we had to. It is true that I had eaten groundhog on camping trips and could name most of the local peaks by sight, but it is also true that I bought incense and spirulina at a health food store in Asheville. I ate more tempeh than I did fatback, and I loved Ani DiFranco and Doc Watson equally.

After graduation, I moved to Boston and became, for the first time, an outsider. Like so many before me, it took leaving home to understand it. I suddenly saw details in contrast and became proud of my heritage. I grew tomatoes on the fire escape because it connected me to my Granny, whose tomatoes were a month ahead and a foot taller. As distance helped me understand what it meant to be from the mountains, I began to deeply miss them. I felt like Ivy Rowe in Lee Smith’s Fair and Tender Ladies who says that she’s like her daddy because she needs a mountain to “set her eyes against.”

I took my groceries from a buggy and put them in a cart. I (nearly) stopped calling my hat a toboggan. I forced my vowels into shape. It worked. I got into graduate school. I got a PhD. I learned to pass. But I lost my voice.

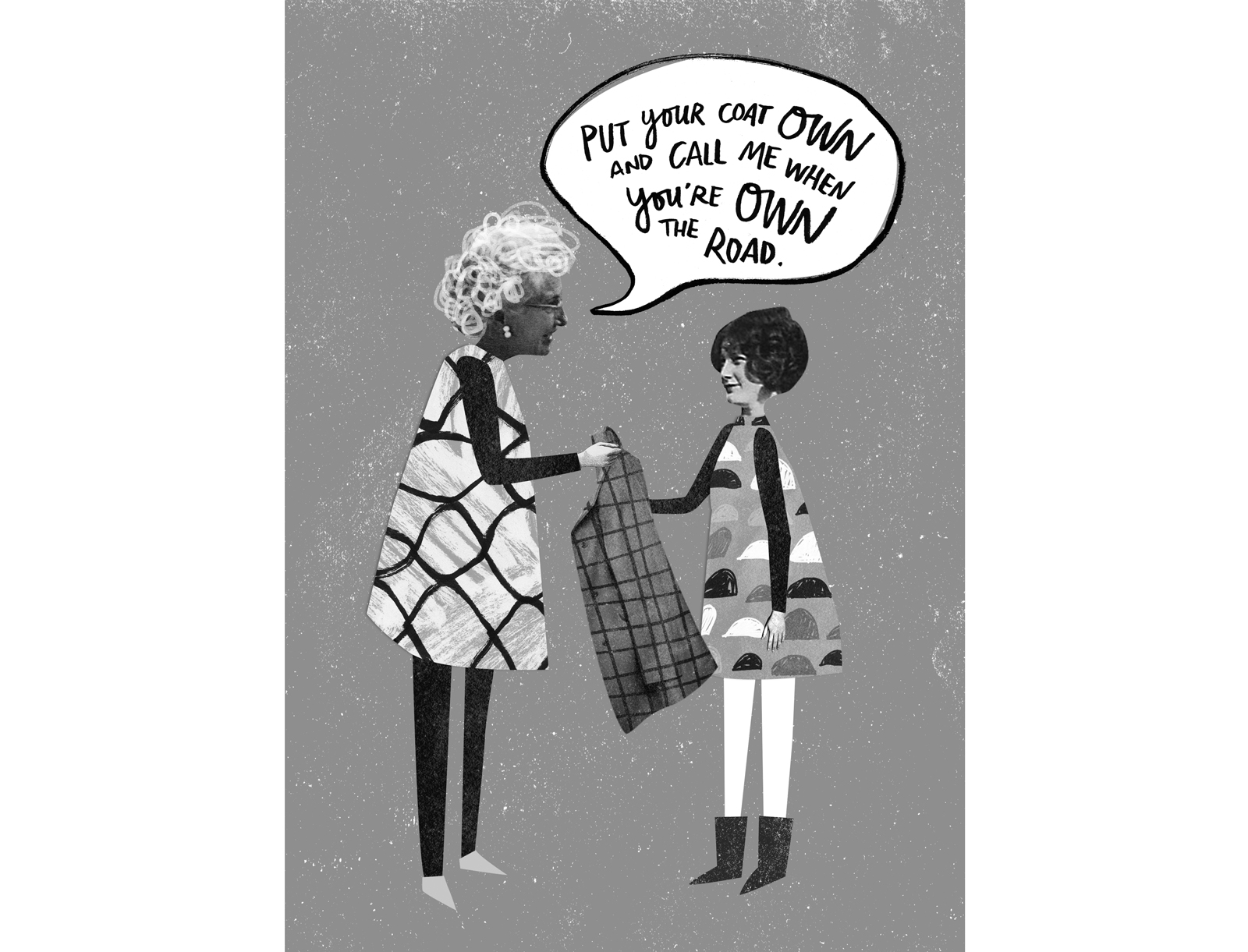

Yet while I was proud of my home, I was also learning that powerful stereotypes about Appalachia had arrived in places like Boston well before me and had influenced the way that even the most considerate people thought about me. The banjo lick from Deliverance backed many introductory conversations when I said where I was from. Instead of calling people out for their ignorance, I distanced myself from Haywood County. I laughed along. I waited longer and longer to reveal my background. I blended in. During this time, I applied to graduate school. In my visits to prestigious universities in Boston, I actively tried to “talk right” and hide my accent. One lingering linguistic marker caused me the most panic when I slipped. Long after I attached ‘G’s to my gerunds and bleached out the local color from my language, I stumbled over the word “on.” When my mom told me to put my coat on, those words rhymed. She told me to call her when I was on the road. And those words rhymed. To my Appalachian tongue, “own” and “on” were pronounced exactly the same way. But not for the rest of the world, I learned. This reminder that I was not from around here meant, to me, that I might not belong in a Boston graduate school.

I learned to always use adverbs. I took my groceries from a buggy and put them in a cart. I (nearly) stopped calling my hat a toboggan. I forced my vowels into shape. It worked. I got into graduate school. I got a PhD. I learned to pass. But I lost my voice. With Granny’s chiding in my ear—“You’re talking uppity now that you live in Baaaaahston”—I developed a new way of speaking. And it wasn’t until a decade later that I heard my own repressed voice echoed back to me in West Virginia.

Writer and activist Silas House spoke at a conference addressing the theme of “New Appalachia,” urging his audience to bring LGBTQ civil rights issues into our classrooms, our scholarship, and our conversations in order to make Appalachia a safer place. New Appalachia, for House, was tied to Old Appalachian activism. As soon as he began speaking, I began to understand the new in light of the old. Combined with a quiet thoughtfulness, his manner of speaking awakened in me memories that I had long put to rest. In one moment, his voice cracked as he was overcome with emotion remembering the violence enacted upon queer youth in Appalachia. Throats tightened across the room. He paused and then said quietly, “And it will go on and on and on . . . ” until we—teachers and writers and students in this room—commit to change. To an outsider, it might have sounded like he was saying “own and own and own,” but when I heard Silas House repeat this word in this context, I felt the ground shift beneath me. Because while he talked about justice, I heard the timbre of my Pa. As he read his own poetry, I heard the cadence of my Aunt Betsy. As he addressed his audience, I heard my mom talking. I heard established scholars speak in accents and it did not change the content of what they were saying. It did not change the power of their intellect. Then I stood up to deliver my paper about the politics of representation in Appalachian film. My ‘G’s were intact. My vowels stood up straight. My “on” was not my “own.” And I felt a powerful loss—of my own voice, my own accent.

Television shows, movies, and cartoons rely lazily on the assumption that viewers will associate a southern accent with a lack of intelligence. It is still acceptable in popular discourse to mock “rednecks” and “hillbillies.” “Reality” shows exoticize Appalachia as a safer space to show how the other half live, without much interrogation of authenticity. People say to lighten up. It’s just a movie. It’s just a TV show. It doesn’t matter. But it does. It mattered to me as I left home, thinking that the only way to be a legitimate scholar was to attend college in New England and change my voice. I had learned to talk right, but I had gotten it all wrong.

I can’t change the fact that my Granny’s great-granny was raised as a white girl after her biological parents had to leave her on the Trail of Tears. Passing for white, she had no choice but to assimilate to her surroundings to fit in. I’m unable trace my way back to that culture that was taken from her and connect to a past that was not allowed to happen. But I can claim the past that I have known. Now that I have learned to articulate issues about representation and gender politics, I want to do so in my own voice—to let my vowels relax into to the shape that they wanted to take all along. I want to honor the voices that were the soundtrack to my upbringing and respond to the calls of Uncle Joe, Granny, Aunt Lena, Aunt Betsy, Pa, and Mom. I want to draw thick that perforated line to my past. I want to claim the voices belonging to my people.

When my mom told me to put my coat on, those words rhymed. She told me to call her when I was on the road. And those words rhymed. To my Appalachian tongue, “own” and “on” were pronounced exactly the same way.

Granny mostly made clean, patterned quilts with a recognizable order. But her mother-in-law made crazy quilts, piecing together scraps and favorites, remnants and set-asides. Combined, polka dots, solids, and gingham formed something alluring beyond any pattern. I loved these crazy quilts and as I struggled my way through my first stitching, I thought that perhaps that style would be easier than the log cabin quilt I had settled upon. Knowing this wasn’t the case, Granny took one of Ma’s quilts down and with few words taught me how to judge it. Flipping it over, she revealed the even, measured hand stitching that held the mismatched pieces together. In it I saw how a thing is made whole, how the intricate gathering together of the unlikely can make sense. I am reminded of it now when I consider the seemingly disparate layers of my own voice and identity—multi-generational Appalachian, first generation college graduate, economically privileged, queer, feminist, antiracist, mother, writer, teacher. I am reminded of that quilt when I look around and see the multiple ways to be Appalachian and to speak Appalachian. Perhaps with some attention, the voices of the past will not be lost but can find a way to go on and on and on.

Meredith McCarroll was born and raised in Western North Carolina. Her evolving research focuses on regional and racial identity, and her book Unwhite: Appalachia, Race, and Film is forthcoming from University of Georgia Press. McCarroll is the Director of the Writing and Rhetoric at Bowdoin College. She lives with her family in Portland, Maine, where she works diligently to maintain her accent.

Natalie Nelson is an illustrator who draws, paints, bikes, and eats in Atlanta, Georgia. Her work has appeared in many publications, including the New York Times and the Washington Post. Her first picture book, The King of the Birds, a tale inspired by the life and bird-collecting habits of Flannery O’Connor, will be published this fall with Groundwood Books. See her work at natalieknelson.com.