In the cotton counties along the river in Mississippi, where there are three black skins for every white one, the gentlemen are afraid. But not of the Negroes. Indeed, the gentlemen and the Negroes are afraid together. They are fearful of the rednecks . . .who in politics and in person are pressing down upon the rich, flat Delta from the hard, eroded hills. They may lynch a Negro; they may destroy the last of a civilization which has great vices and great virtues, beauty and strength, responsibility beside arrogance, and a preserving honesty beside a destructive self-indulgence.

—Jonathan Daniels, A Southerner Discovers the South (1938)

Arkie, clay-eater, corn-cracker, compone, cracker, dirt-eater, hillbilly, hoosier, lowdowner, mean white, peckerwood, pinelander, poor buckra, poor white, poor white trash, redneck, ridge-runner, sandhiller, tacky, wool hat. . . . And this, of course, does not exhaust the list. Rural poor and working-class white southerners have endured a broad range of slurs throughout US history, many derived from geographic regions, dietary habits, physical appearance, or types of clothing. Epithets aimed at urban poor white southerners are fewer and tend to focus on cotton-mill workers: cottonhead, cotton mill trash, cottontail, factory hill trash, factory rat, and linthead, for example. A few of the rural class slurs, especially redneck and hillbilly, are also applied indiscriminately to southern white migrants working in factories in Chicago, Detroit, Cincinnati, and other midwestern cities.1

For approximately the last one hundred years, the pejorative term redneck has chiefly slurred a rural, poor white man of the American South and particularly one who holds conservative, racist, or reactionary views. In 1965, for example, John Silber backhandedly praised President Lyndon Baines Johnson of Texas: “His manner and accent suggest a person who might hold the racist views of a red-neck Southern bigot[,] yet he has shown a moral vision as clear as Lincoln’s on the race question.” Working-class white southerners are today, along with feminists and gays and lesbians, among the few groups that one can publicly insult or lampoon with impunity. As southern historian C. Vann Woodward puts it, redneck is “the only opprobrious epithet for an ethnic minority still permitted in polite company.”2

But southern white working people—often poor, powerless, and nonliterate—have not accepted their place in the popular imagination without a fight. Rather they have time and again rehabilitated the derogatory stereotypes ascribed to them by using language to fashion an identity as honest, hard-working common folks. A good example of this identity-making process can be found in the changing definitions and connotations of redneck in the American language. The term redneck originated as a class slur in the late-nineteenth-century South, but white blue-collar workers—especially, but not exclusively, those from the South—gave it a complimentary meaning in the late twentieth century. The redefinition and use of the term by these self-styled rednecks speak powerfully to their racial and class consciousness as an economically exploited and yet racially privileged group.

The Etymology of Redneck

The term redneck emerged as a class slur in the lower Mississippi Valley region sometime in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The word did not appear in print, however, until late in the century.3 According to the Oxford English Dictionary, one of its earliest examples came in 1893 when Hubert A. Shands reported that red-neck was used in Mississippi speech “as a name applied by the better class of people to the poorer [white] inhabitants of the rural districts.” Eleven years later Joseph W. Carr heard the epithet in Fayetteville, Arkansas, where professional and middle-class whites used the term to refer to “an uncouth countryman” from the swamps, as opposed to a hill billy, “an uncouth countryman, particularly from the hills.” Carr also recorded the expression rednecked hill billy. We do not know how much earlier the slur was in oral circulation among white Mississippians and Arkansans before Shands and Carr noted its use, but it was clearly in widespread currency in white southern speech by the 1930s. Black southerners of all classes, too, used redneck—along with poor white trash, cracker, peckerwood, and a host of other slurs—to poke fun at poor white country folks, whom they regarded as morally and socially inferior to themselves. Black sharecroppers, for instance, challenged the southern racial hierarchy in the twenties and thirties when they hollered while working in the fields: “I’d druther be a n—-r, an’ plow ole Beck / Dan a white Hill Billy wid his long red neck.”4

The compound word redneck, most scholars of the American language agree, originally derived from an allusion to sunburn. The prevailing view is that southern plantation owners and the urban white professional and middle classes coined the epithet to describe those white dirt farmers, sharecroppers, and agricultural laborers who had sunburned red necks from working fields, unprotected, under a scorching sun. Another explanation, however, traces the origin of redneck to Black English and claims that it evolved from peckerwood, another, much older slur for a poor rural white southerner. According to this theory, African American slaves used peckerwood, a folk inversion of woodpecker, to refer to their poverty-stricken white neighbors who had sunburned necks while adopting the blackbird as a symbol for themselves. The red head of the woodpecker may in some way be related to the term redneck.5 Whatever its derivation, the origin and early usage of the slur suggest that it ridiculed not only the sweaty, drudging labor of white farmers and sharecroppers but also their perceived deviation, at least a limited one, from a pale white complexion. From its earliest usage, then, the pejorative term redneck reflected clear connotations of both class and color difference.

A few students of the American language also speculate that southern white farmers and sharecroppers first became “rednecks” after some refused to wear their traditional wool hats any longer to protect them against sunburn. The reason for their refusal, scholars suggest, was a conscious effort to distinguish themselves in dress from the former Black slaves who reportedly began adopting headgear in large numbers only after emancipation. A South Carolina writer lent support to this argument when, in 1877, he observed: “The negro men, as a general thing, did not wear hats before emancipation. But they have since displayed quite a zeal to procure head wear. . . .” More recently, southern journalists Billy Bowles and Remer Tyson have advanced another explanation. They propose that, after the Civil War, the white yeoman farmers of Georgia “stubbornly refused to wear the cool, wide-brim straw field hats favored by their former slaves” and instead opted for “sweaty, narrow-brim wool hats” that exposed their necks to sunburn as they stooped to work in the fields.6 Both of the above explanations underscore the decision of red-necked farmers and sharecroppers to set themselves apart from their Black counterparts. White farmers, whether landowners or tenants, sought to preserve their higher social and economic status and to undercut any opportunity for comparisons of themselves to Black southerners, even at the cost of a painful sunburn. Obviously, a white racial identity held great significance in their minds and in southern culture generally.

The virulent racism of some poor and working-class white southerners also came to be closely associated with the word redneck, and as the twentieth century wore on, it was increasingly used to describe a racist, bigot, or reactionary. In 1938, for example, Harris Dickson, a white Mississippi plantation owner, simply explained to newspaperman Jonathan Daniels, “Rednecks . . . are raised on hate.” Some years later, “Gooseneck Bill” McDonald, a leading Black Republican in early twentieth-century Texas politics, suggested as much, implying that the words redneck and racist were synonymous. “Many of the whites I came in contact with in the country and elsewhere were extremely kind,” McDonald recalled of his many years stumping for the Grand Old Party in the Lone Star State, “and I, for one, don’t believe every Southerner is a ‘redneck.’”7

By the midsixties, the connection between redneck and racism was firmly cemented, especially for African Americans. At Oxford, Ohio, site of the training sessions for the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer, experienced instructors prepared northern college-age civil rights volunteers for the hatred and violence they expected to encounter, using a role-playing game called “Redneck-and-N—-r.” In the scenario, journalist William Bradford Huie explained, “They would choose up [sides] . . . try to see how long they could remain ‘goodnatured and smiling’ while the Rednecks jostled them and called them [racial epithet].” In 1973, during his bid to break Babe Ruth’s all-time home run record, Atlanta Braves slugger Hank Aaron called a racist heckler a “redneck.” In this sense, the epithet has lost many of its class and regional connotations because African Americans apply it indiscriminately to any white racist, regardless of his or her class position or birthplace. “They were rich people, but that girl—oh—but I lived to see her get everything that she put out,” Althea Vaughn, a southern cook and maid, bitterly recalled her white employer’s daughter-in-law. “. . . I couldn’t stand her for nothing in the world. She [was an] old redneck hoo’ger, those kinds that weren’t used to nothing.”8

The Stereotyping of the Redneck

Today the redneck is generally depicted in novels, films, and television shows as a greasy-haired, tobacco-chewing, poor southern white man with a sixth-grade education and a beer gut. He lives in a double-wide trailer with his homely, obese wife—who is probably also a first cousin—and their brood of grubby, sallowfaced children and a couple of scrawny coon dogs. He is, according to the stereotype, a rent farmer, a gas station attendant, or a factory worker, if he works at all. He enjoys guzzling six-packs, listening to country music, and hanging out with his buddies in pool halls and honky-tonks, that is, when he’s not fishing, poaching deer, cruising in his pickup truck, going to stock car races, beating his wife, or attending Klan rallies. And, of course, the redneck supposedly hates Blacks, Jews, hippies, union organizers, aristocratic southern whites, Yankees, and, for good measure, “foreigners” in general.9

In A Turn in the South (1989), a travel account of the southern United States, West Indian writer V. S. Naipaul recounts a conversation with a real estate salesman in Jackson, Mississippi, who provided a colorful description of what he took redneck to mean:

A redneck is a lower blue-collar construction worker who definitely doesn’t like blacks. . . . He is going to live in a trailer someplace out in Rankin County, and he’s going to smoke about two and a half packs of cigarettes a day and drink about ten cans of beer at night, and he’s going to be mad as hell if he doesn’t have some cornbread and peas and fried okra and some fried pork chops to eat. . . . And the son of a bitch loves country music. They love to hunt and fish. They go out all night on the Pearl River. . . . They’re Scotch-Irish in origin. A lot of them intermarried, interbred. I’m talking about the good old rednecks now. He’s going to have an old eight-to-five job. But there’s an upscale redneck, and he’s going to want it cleaned up. Yard mowed, a little garden in the back. Old Mama, she’s gonna wear designer jeans and they’re gonna go to Shoney’s to eat once every three weeks. … If he or she moves to North Jackson, he’d be upscale [sic]. He wouldn’t have that twang so much. But the good old fellow, he’s just going to work six or eight months a year. . . . [The wife’s] got some little piddling job. She’s probably the basis of the income. She’s going to try to work every day. . . . You see, he doesn’t want to work all day long. He’s satisfied by getting by. They don’t like to be told what to do. . . .They have the same old attitude as the black people. Daddy is home a little more often. But they’re tickled pink that they ain’t got nothing. You wouldn’t believe.10

While the real estate agent obviously knew his subjects intimately enough to notice the intricate nuances of consumption patterns and class differences, his description reflects stereotypes that are prevalent in popular culture.

The image of the redneck as a vicious, cross-burning racist is also widespread. In his song “Rednecks” from the 1974 concept album Good Old Boys, singer and songwriter Randy Newman comically depicts southern working-class whites as ignorant and belligerent hatemongers who “don’t know [their] ass from a hole in the ground” and who are trying to keep “the n—–r down.” While he doesn’t challenge the redneck stereotype, he does point out the hypocrisy of singling out southern white working people as the only racists in America. Not surprisingly, Newman’s benighted redneck persona composes the song to defend Lester Maddox, the ax handle–wielding governor of Georgia, and his fellow southern rednecks against the mockings of “some smart-ass New York Jew.” Yet he ironically and insightfully declares that “the North has set the n—-r free”—but only “free to be put in a cage” in northern ghettos. Even a few country-and-western songs embrace the stereotype. For example, the Charlie Daniels Band’s “Uneasy Rider” (1973) and Kinky Friedman’s “They Ain’t Makin’ Jews Like Jesus Anymore” (1974) depict rednecks as intolerant small-minded bigots who hate Blacks, Jews, and hippies with equal passion.11

A host of popular jokes reinforces the negative stereotypes of rural southern white folks. Most of these jokes seem to be made up and told by middle-class whites—southerners as well as northerners—and are occasionally heard on cabletelevision comedy shows. Comic Jeff Foxworthy of Georgia has turned redneck humor into a cottage industry, publishing three best-selling books containing a total of more than four hundred jokes. Redneck and hillbilly jokes primarily poke fun at the stereotypical lower-class lifestyles, values, and manners of rural white southerners, especially their image as lascivious yokels given to drunkenness and sexual excess—often including bestiality, incest, and other aberrant sexual practices. “You might be a redneck,” one Foxworthy joke goes, “if you’ve ever heard a sheep bleat and had romantic thoughts.” And another: “You might be a redneck if you view the upcoming family reunion as a chance to meet women.”12

Redneck and hillbilly jokes not only ridicule and denigrate but also marginalize their subjects and mark group distinctions in much the same way as other ethnic and racial humor. They, in effect, convey exaggerated characterizations of rural white southerners that outsiders actually believe to be accurate. This is strikingly evident in the comments of Tony Isaac, a gay man from Michigan who cruised Chicago’s “hillbilly bars” for sexual partners during the 1950s. “You found out that hillbillies first wanted a woman,” Isaac concluded of his honky-tonk encounters with recently-arrived southern white migrants, “and if they couldn’t get a woman they’d take anything. I think they’d rather have a cow than a man but they’d take a man.”13

Questions of Race and Class

To explain why poor and working-class white southerners have borne a disproportionate share of insults and stereotypes, we must begin by looking at the development of racial and class identity in the nineteenth-century South. Throughout that century and beyond, planters, overseers, and factory owners took advantage of such stereotypes of poor southern whites as a justification for exploiting them and paying them pitifully low wages. An Augusta, Georgia, cotton mill owner remarked, for instance, to traveler William Cullen Bryant of his female workers in 1849:

These poor girls . . . think themselves extremely fortunate to be employed here, and accept work gladly. They come from the most barren parts of Carolina and Georgia, where their families live wretchedly, often upon unwholesome food, and as idly as wretchedly. . . . They come barefooted, dirty, and in rags; they are scoured, put into shoes and stockings, set at work and sent regularly to Sunday-schools, where they are taught what none of them have been taught before—to read and write. In a short time they become expert at their work; they lose their sullen shyness, and their physiognomy becomes comparatively open and cheerful. Their families are relieved from the temptations to theft and other shameful courses which accompany the condition of poverty without occupation.14

Other antebellum employers used stereotypes of southern white workers to rationalize the hiring of Black slave or Irish immigrant laborers instead. Frederick Law Olmsted, a New Yorker who toured the southern coastal states extensively in the 1850s, frequently commented on the absence of native-born, white workingmen in southern agricultural work, canal-building, and other unskilled jobs. The planters and other employers whom he questioned repeatedly told him that they did not hire “poor whites” because such men “are not used to steady labour; they work reluctantly, and will not bear driving; they cannot be worked to advantage with slaves, and it is inconvenient to look after them, if you work them separately.”15

Southern white workers, nevertheless, clung to their racial identity. From the nation’s beginning, notions of whiteness and Blackness developed in relation to one another in the South within the context of racial slavery, and eventually, whiteness became, by the turn of the nineteenth century, closely associated with the republican virtues of freedom, independence, and manliness. At the same time, Blackness came to symbolize its opposite qualities of slavishness, dependence, and emasculation. “Euro-American culture in general valued a pale complexion,” historian Elizabeth Fox-Genovese writes, “but to [white] southerners paleness assumed special importance by implicitly distancing [them] from the dark skins of Africans.” In effect, the nonslaveholding masses of southern white men—small farmers, herders, squatters, day laborers, hunters, overseers, and riverboat hands—prized their racial identity because it distinguished them as free men and entitled them to political and civil rights. As Emily P. Burke, a New Hampshire native who taught school in Georgia during the 1840s, observed, the masses of “crackers, clay-eaters, and sandhillers” in the state, “though degraded and ignorant as the slaves, are, by their little fairer complexions entitled to all privileges of legal suffrage.” Race alone accorded poor whites a sense of superiority over Blacks, slave and free, “a sort of public and psychological wage,” historian W. E. B. Du Bois wrote in 1935. Of the lower classes of southern whites, Du Bois asserted:

They were given public deference and titles of courtesy because they were white. They were admitted freely with all classes of white people to public functions, public parks, and the best schools. The police were drawn from their ranks, and the courts, dependent upon their votes, treated them with such leniency as to encourage lawlessness. Their vote selected public officials, and while this had small effect upon the economic situation, it had great effect upon their personal treatment and the deference shown them.16

A pale white complexion also symbolized respectability, gentility, and social status in the antebellum South, since planters and ladies, like the nobility and gentry of Europe, did not perform manual work but rather reaped the fruits of others’ labor. In contrast, a sun-browned skin served as a badge of agrarian toil, and few northern and European travelers missed a chance in their journals to comment on the dark, weathered complexions of southern white farmers and laborers. In 1817, for example, British traveler Elias P. Fordham described the differences of skin color that he noted among the white classes of Virginia. “The gentlemen [here] are fairer than Englishmen,” he observed, “their faces being always shaded by hats with extraordinary broad brims,” while “the poorer people and the overseers are very swarthy.” A fair-skinned complexion, then, was not only an index of race but also an index of class.17

Although most were not slaveholders themselves, the masses of rural white southerners were often staunch champions of slavery because it established them in a superior social position to at least some people in southern society. According to southern historian Steven Hahn, white yeoman farmers and other small landholders “saw blacks as symbols of a condition they most feared—abject and perpetual dependency—and as a group whose strict subordination provided essential safeguards for their way of life.” Fanny Kemble, an English actress who lived on a Georgia Sea Islands plantation during the late 1830s, claimed: “To the crime of slavery, though they [poor white southerners] have no profitable part or lot in it, they are fiercely accessory, because it is the barrier that divides the black and white races, at the foot of which they lie wallowing in unspeakable degradation, but immensely proud of the base freedom which still separates them from the lash-driven tillers of the soil.”18

One example of rural southern white workers’ efforts to maintain clearly defined economic and social distinctions between themselves and African Americans was these workers’ occasional refusal to work under the supervision of a gang boss, or to perform certain types of agricultural wage labor such as tending cattle and hauling wood. They saw these tasks, traditionally performed by slaves, as work that was beneath white folks, even the lowliest and most destitute, because it reduced them to a certain degree of equality with Black southerners. As Frederick Law Olmsted explained, “To work industriously and steadily . . . is, in the Southern tongue, to ‘work like a n—-r’; and from childhood, the one thing in their condition which has made life valuable to the mass of whites has been that the n—–s are yet their inferiors.”19

Ironically, this tactic to control their own labor won the masses of poor white southerners a reputation for being lazy and shiftless. Antebellum travelers and social observers condemned what they perceived as the laziness of poor white folks and their disdain for manual labor, and abolitionists in particular argued that manual work in the southern states was, as Fanny Kemble asserted, “the especial portion of slaves, [and] it is thenceforth degraded, and considered unworthy of all but slaves. No white man, therefore, of any class puts hand to work of any kind soever.” Touring the war-torn southeastern seaboard states in late 1865, northern newspaper correspondent Sidney Andrews reported that “there can be no lower class of people than the North Carolina ‘clay-eaters.’” Andrews believed that “the average negroes are superior in force and intellect to the great majority of these clay-eaters,” who, he wrote, “are lazy and thriftless, mostly choose to live by begging or pilfering, and are more unreliable as farm hands than the worst of the negroes.”20

After emancipation in 1865, slavery no longer provided a sharp distinction between white and Black southerners. Despite the dire poverty, homelessness, and hunger that many poor white families suffered after the Civil War, white workers to a large degree remained steadfast in their refusal to do so-called “n—-r work.” True, some poor southern white men deliberately conformed to their imposed stereotypes and manipulated them by feigning ignorance or incompetence to avoid trouble or punishment from those more powerful than themselves. Slaves had sometimes done the same thing before them with the image of the shuffling, grinning Sambo. But this form of resistance was all too often self-defeating since it usually served only to reinforce dehumanized images of the group.21

The strategy certainly reinforced the views of industrious-minded factory owners and Victorian reformers who condemned poor southern white men for supposedly shirking their patriarchal responsibilities as family providers and instead placing the burden of their families’ subsistence on their wives and daughters. Thus, these men forfeited any claim to manhood, honor, and respect, according to critics. In 1891, Clare De Graffenried, a US Bureau of Labor investigator studying cotton mill workers in Georgia, put into words a stereotype that remains current today:

The genius for evading labor is most marked in the men. Like Indians in their disdain of household work, they refuse to chop wood or bring water, and often subsist entirely upon the earnings of meek wives or fond daughters, whose excuses for this shameless vagabondism are both pathetic and exasperating. . . . The favorite occupation of the men is to spit, stare, and whittle sticks.22

As the New South began a spurt of industrialization in the 1880s, the promise of steady work and wages drew masses of rural white southern men and women to mills and factories. Again industry boosters used the popular stereotype of poor rural white folks to promote the social benefits of industrialization and to rationalize “the creation of a dependent, wage-earning white working class.” Factory work and a capitalist work discipline, the owners argued, would civilize and transform shiftless “poor white trash” into productive, respectable citizens of southern society.23

For southern white workers factory jobs conferred not only a livelihood but also social and economic status since many owned no property and had nothing to sell but their labor. Consequently, they collaborated with factory owners to maintain rigidly segregated workplaces in the increasingly industrialized New South. In textile mills that sprang up in the Carolina and Georgia piedmont, for example, white workers demanded that all production line jobs be reserved for whites only and that Black workers be restricted to such menial, undesirable jobs as sweepers, scrubbers, yard hands, and firemen. Such employment practices contained a trade-off for white mill workers. On the one hand, they protected their social and economic status as wage workers and gained a certain amount of job security by restricting the pool of unskilled laborers from which management could draw its employees. On the other hand, they accepted lower wages in return. For their part, textile mill owners benefitted from a less militant white workforce that identified not so much with the class interests it shared with Black workers as it did with the racial interests of its employers. A racially divided workforce, moreover, dealt textile mill owners a trump card—the threat of replacing white strikers with Black strikebreakers.24

These racist employment practices, as historian I. A. Newby has shown, were widely adhered to by textile mill owners throughout the South during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. A 1907 survey of 152 southern textile mills, for example, found that none employed Black men on the production line and that only a handful employed them to work outdoors. Any breach of segregated employment in mills and factories could result in outbreaks of lynchings and in other forms of racial violence against Black workers or in labor strikes. Between 1882 and 1900, southern white workers in textile, railroad, and other industries staged at least fifty strikes to protest the employment of Black workers in any but the dirtiest, lowest-paying, and most physically difficult jobs.25

One of the most famous of these strikes occurred at the Fulton Bag and Cotton Mills in Atlanta, Georgia, in August 1897, when more than 1,400 white mill workers walked off their jobs to protest the hiring of twenty-five Black women as folders on the production line. The striking mill workers were outraged over management’s suspension of racist hiring practices, despite the fact that the Black folders worked in a segregated department of the mill. The strikers’ demands were simple but carried significant meaning for their social and economic status as wage workers. “All we want you to do,” a spokesman for the strikers told the president of Fulton Mills, “is to take out the n—–s from this place, all except the scrubbers and the fireman.” The strike lasted five days and resulted in an “overwhelmingly favorable” settlement for the strikers. No disciplinary action was taken against them, and the Black folders were fired. Thus, the united white mill workers had successfully forced the company to make a major concession to their job security and to working-class respectability, and particularly to working-class white womanhood.26

The Pain of Prejudice

It would be a mistake, however, to see the creation of rural southern white stereotypes as overtly conscious acts or to think that only a small segment of American society actually believed, maintained, and reproduced these stereotypes. Rather, they have long held wide currency among all classes of Americans, white and Black alike, as realistic depictions of the poor white southerner. Many outsiders unfamiliar with southern white working people fear and intentionally avoid them on the basis of the negative, antisocial images. The Chicago Tribune, for example, reported in the late fifties that the city had been invaded by “clans of fightin’, feudin’, Southern hillbillies and their shootin’ cousins,” a reference to the approximately seventy thousand white migrants who left Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, and Missouri during and after World War II in search of jobs in Chicago’s factories, meatpacking houses, and stockyards. “The Southern hillbilly migrants, who have descended like a plague of locusts in the last few years,” the paper continued, “have the lowest standard of living and moral code (if any), the biggest capacity for liquor, and the most savage tactics when drunk, which is most of the time.” Midwesterners’ fear of and hostility toward the migrants are also reflected in a 1951 Wayne State University study of Detroit residents, in which 21 percent of those surveyed identified “poor southern whites/hillbillies” as the most “undesirable people” who were “not good to have in the city” while only 13 percent of the respondents named “Negroes” and another 6 percent “foreigners.” Only “criminals/gangsters,” selected by 26 percent, ranked higher.27

Rural southern white stereotypes are often as powerful as other racial, religious, or ethnic prejudices. Listen, for instance, to Charles Strong, a Black Vietnam War veteran from Pompano Beach, Florida, describing a white soldier in his company with whom he became close friends: “Joe was an all right guy from Georgia. . . . He talked with that Ol’ dude’ accent. If you were to see him the first time, you would just say that’s a redneck, ridge-runnin’ cracker. But he was the nicest guy in the world.” Strong was challenged and shocked by his previously almost unimaginable friendship with a “redneck, ridge-runnin’ cracker” and was forced to rethink his prejudices—a painful but often enlightening experience.28

The epithets hurled at poor and working southern white folks can also be as damaging psychologically as slurs aimed at other minority groups. Victims often internalize the hateful messages of epithets, making them difficult to forget or escape. The point is made in a 1939 Federal Writers’ Project interview of Jessie Jeffcoat, the wife of a third-generation sharecropper living in Durham County, North Carolina. “You ain’t nothing but pore whites [sic],” a rich man’s son cruelly teased Jessie’s husband, Jim Jeffcoat, when he was a young boy growing up in northeastern Georgia. Later in his life, unable to rise above his poverty and to purchase his own land and mules, Jim Jeffcoat drank heavily and drifted from one farmstead to another. Jessie Jeffcoat confided that she believed that the “poor white” stigma was the cause of her husband’s alcoholism. “Nobody ever called him ‘pore white’ anymore,” she said. “But Jim still believes that people are thinkin’ it. When they cuss him or ‘pore Jim’ him, he gets sore and keeps rememberin’ and rememberin’ that his folks were down near the bottom before the [Civil] War. Mister, I believe that’s one reason Jim drinks so much. The only time he forgets that he came from pore folks is when he gits drunk [sic].”29

The Redefinition of Redneck

Not all southern white working people remained victims of these damaging stereotypes and hateful slurs, however. Positive definitions of redneck also emerged. As early as 1910, for example, political supporters of Mississippi demagogue James K. Vardaman described themselves as “rednecks.” Vardaman’s constituency, comprised largely of poor and working-class white Mississippians, embraced the epithet and wore red neckties and kerchiefs to his political rallies to show their support for the candidate during a special Democratic senatorial primary race against opponent Leroy Percy. Historian Albert D. Kirwan, in Revolt of the Rednecks: Mississippi Politics, 1876–1925 (1951), explains their adoption of the nickname:

In a speech at Godbold Wells on July 4, 1910, Percy, heckled by an audience with shouts of “Hurrah for Vardaman!” “Hurrah for [Theodore] Bilbo!” “Hurrah for Mary Stamps!” became angered and called them “cattle” and “rednecks.” These names were adopted by the Vardaman following, and wherever Vardaman went to speak he was greeted by crowds of men wearing red neckties and was carried in wagons drawn by oxen. This accentuated the class division in the struggle.30

Yet it was not until the late 1960s and early 1970s that large numbers of poor and working-class white southerners began referring to themselves as “rednecks.” Perhaps they chose this name partly because it conveyed their own emergent sense of racial and class solidarity in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement, the counterculture revolution, and the women’s liberation movement. In this sense the selection of the term may have been part of a larger southern white backlash to the social upheavals of the sixties. Regardless of the reasons for its widespread emergence, southern white workers redefined redneck to emphasize their industriousness and their white racial identity. As one blue-collar workingman told sociologists Julian B. Roebuck and Mark Hickson III: “Us rednecks are jes God-fearing Christians who don’t cheat like n—–s and the rich white man.” As this quote suggests, rednecks first define themselves in relation to Black Americans by accentuating their whiteness, from which they derived economic and psychological benefits. 31

Their identity involved more than race, however. Like the populist farmers of Georgia and South Carolina who termed themselves “wool hats” in the 1890s, modern-day self-styled rednecks define themselves in relation to southern white society by using the term redneck to mean an honest, hard-working workingman who identifies with traditional southern social and religious values. The chief characteristic that rednecks felt distinguished them from the other classes of white southerners is their masculine ethic of a hard, honest day’s work. They see themselves as different from the “poor white trash,” who are cast as lazy, good-for nothing folks who never work but instead sponge off welfare as Black people supposedly do. Nor are they like the “big shots”—money-grubbing upper- and middle-class southerners who exploit and get fat off workers’ labor rather than doing honest work themselves. “We’re jes po honest working folks who work for an honest day’s pay,” one self-avowed redneck explained. Another rankled redneck ranted, “Folks like us work for a livin’. The big guys are a bunch of phonies, know what I’ma talkin’ bout?—phonies and bullshitters.”32

In the mid seventies a combination of political events and popular culture catapulted the word redneck to national attention. In 1978, for example, an obscure band named The Beaver Brothers released a song titled “Redneck in the White House” in the wake of a spate of country songs that celebrated the southern redneck as a working-class hero. That redneck in the White House was, of course, Jimmy Carter of Georgia, a wealthy peanut farmer and professional politician whose neck struck others as actually more pink than red. Nonetheless, Carter sometimes described himself—and during the 1976 presidential campaign was even sometimes described by Washington political reporters who didn’t know any better—as “basically a redneck.” He successfully ran as a self-styled “political outsider,” a slick man-of-the-people packaging obviously designed for political purposes.33

It was the president’s beer-drinking, straight-talking brother, Billy Carter, however, who came to epitomize the “genuine” redneck better than any other American public figure. The press hailed him as “America’s newest folk hero,” and Brother Billy, a self-avowed redneck, played the part admirably. On occasion he hammed for photographers in his “Redneck Power” T-shirt, with a cold Pabst Blue Ribbon in hand, or regaled reporters with his down-home anecdotes at his Plains, Georgia, filling station. In effect, Billy Carter embodied those characteristics that rednecks promoted in their campaign of self-definition. When his brother Jimmy ran for office in 1976, touting his own honesty, Billy told the press, “I’m the only Carter who’ll never lie to you.” On another occasion he identified his mainstream American lifestyle and values, remarking, “My mother joined the Peace Corps when she was seventy, my sister Gloria is a motorcycle racer, my other sister Ruth is a Holy Roller preacher, and my brother thinks he’s going to be President of the United States. I’m really the only normal one in the family.” For Americans disillusioned and embittered by Watergate and a lengthy Asian war, Billy Carter marked a refreshing return to those supposedly good old all-American values of honesty, hard work, pride, self-reliance, and commonness.34

To identify oneself as a redneck became fashionable during the Carter years, a national craze that writer and journalist Paul Hemphill termed “redneck chic.” Suddenly, trendy white Americans across the country affected phony southern drawls, dressed up in Levi’s and cowboy boots, sipped Lone Star and Pabst longnecks, tuned into Waylon and Willie, and hankered for meals of fried pork chops, grits, greens, and biscuits and gravy. “Redneck chic”—which anticipated by half a decade the western-wear and bull-riding fad created by the blockbuster hit film Urban Cowboy (1981)—spawned its own distinct body of literature, to use the term loosely. Dozens of books and articles were published to teach redneck wannabes how to stomach greasy home cooking, speak with a proper accent, chug six-packs, fashionably dress down, chew tobacco and spit without opening their mouths, and convincingly act the part. One example was Nina Savin’s 1981 article, “The Official Redneck Handbook,” which appeared, oddly enough, in Fashion For Men. “Rednecks are cool. Not in an affected way, but fundamentally,” Savin explained.35

Meanwhile, the term redneck cropped up in more and more country songs, with many of the singers referring to themselves as one: David Allan Coe’s “Longhaired Redneck” (1975), Vern Oxford’s “Redneck! (The Redneck National Anthem)” (1976), Jerry Reed’s “(I’m Just a) Redneck in a Rock and Roll Bar” (1977), and Ronnie Milsap’s “I’m Just a Redneck at Heart” (1983), to name only a handful. More often than not, country songs presented romanticized images of southern rednecks and frequently used the term as an affirmation of identity. Johnny Russell’s well-known recording of “Rednecks, White Socks and Blue Ribbon Beer” (1973), for instance, celebrates the lifestyle of southern blue-collar workers who “don’t fit in with that white-collar crowd” and who are “a little too rowdy and a little too loud.” More recently, The Charlie Daniels Band’s solution to America’s domestic problems, titled “(What This World Needs Is) A Few More Rednecks” underscores the term’s emphasis on commonness, true grit, and hard work. A redneck, Daniels sings, is a working man who “earns his living by the sweat of his brow” and by “the callouses on his hands.”36

Some rock ’n’ roll songs also traded on the positive redefinition. In “Texan Love Song” (1972), British singer and songwriter Elton John’s working-class hero threatens long-haired, drug-smoking hippie interlopers with violence, asserting, “We’re tough and we’re Texan with necks good and red.” And Jan Reid coined the phrase redneck rock for his book, The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock (1974), to describe the fusion of traditional country-and-western and rock ’n’ roll pioneered in the early seventies by Michael Murphey, Willie Nelson, Jerry Jeff Walker, Kinky Friedman, and others involved in the avant-garde music scene in Austin, Texas. The terms country rock, progressive country, and southern rock were among the other catchy names created to refer to this hybrid of musical styles, and eventually its definition was extended to include such southern supergroups as the Allman Brothers Band, Lynyrd Skynyrd, and the Marshall Tucker Band.37

Used to mean a poor southern white man or worse, the term redneck is still considered an insult when used disrespectfully. But today, self-styled rednecks define themselves, and are even defined by some outside their group, as honest, hard-working, blue-collar white Americans with mainstream attitudes and values. University of Georgia historian F. Nash Boney, for example, argues, “In many ways rednecks are typical Americans with typical American attitudes. They as much as any group in our culture are representative Americans.” The titles of both Randy Howard’s “All-American Redneck” (1983) and John Schneider’s “A Redneck Is the Backbone of America” (1987) emphasize this point. According to these two little-known country songs, rednecks are not only America’s brawny workingmen and its chief producers but also the country’s steadfast patriots and its moral pillars. In the latter song Schneider lionizes the redneck whose “heart [is] full of love for his family, his neighbors, his country” and who is “the reason this nation stands.” Female derivatives of redneck, a traditionally masculine term, have also emerged, including redneck girl, redneck mother, and redneck woman.38

Even some white Americans who are neither of southern descent nor of working-class origins have adopted the term redneck. In 1977, for example, Sheriff Duane Lowe of Sacramento, California, a controversial political hard-liner and antihomosexual crusader, told an interviewer: “My detractors characterize me as a reactionary and as a redneck. And I’ll tell you, I don’t mind being called a redneck.” Among blue-collar white workingmen, use of the word has spread beyond the South. Perhaps a Pittsburgh steel-mill worker, a Washington State logger, or a Detroit auto worker is as likely to describe himself as a redneck as is a Mississippi cotton farmer, a Birmingham construction worker, or an Atlanta mechanic. Moreover, no small number of professional and middle-class white southerners now refer themselves as rednecks. “Some big shots is necks, too. . . . Fact is, it’s hard to tell who be and who ain’t a redneck,” one blue-collar worker remarked. And another said: “Shit, anybody can be a redneck; it ain’t who you be—but how you think.” The real estate salesman interviewed by V. S. Naipaul marked distinctions between the rougher, lower-class “good old rednecks” and the more respectable, upwardly mobile “upscale rednecks.” “I’m probably a redneck myself,” the realtor added. Undoubtedly, an “upscale” one.39

The widespread success of redneck as a symbol of southern pride stems primarily from its synthesis of whiteness and industriousness, two attributes that historically have been central to the identity of the southern white working classes. First, redneck emphasizes a white racial identity. Although it denotes redness, the word ironically connotes whiteness because, as an allusion to sunburn, it naturally follows that only fair-complexioned persons sunburn or, rather, burn red. As one hack writer of humorous southern travel guides for “Yankees” curiously phrases it: “The South is [where], no matter how long he works in the sun, a black man never becomes a Red Neck.”40

Second, redneck emphasizes the masculine values of hard, honest labor, a connotation that likewise stems from its origin. Since it evolved from an allusion to sunburn, redneck initially referred to a farmer who toiled for long hours exposed to the beating sun. In 1938 Jonathan Daniels cautioned readers of A Southerner Discovers the South that “rednecks” should not be confused with “po’ whites,” pointing out that “[Abraham] Lincoln and [Andrew] Jackson, to name but two, came from a Southern folk the back of whose necks were ridged and red from labor in the sun.” In other words, self-described rednecks did not see themselves as the shiftless “poor white trash” of the popular imagination who lolled about on hot afternoons in the cool shade, intermittently suckin’ on a jug of whiskey and dozing, while his long-suffering wife and daughters chopped wood and worked the land. Instead, they viewed their primary male role as family protector and provider, responsible for holding down a steady job, caring for their dependents, putting food on the table, and earning enough to make ends meet. As one southern blue-collar workingman remarked: “Hell with that ejacation [education] shit. . . . Me, I’d druther work. And alia my kids I’ma hoping will go to work early. Don’t tell me about no future bullshit. My family’s gotta eat today.” Rejecting some of the bourgeois notions of manhood, rednecks fashioned their own code of working-class masculinity and respectability which placed a high premium on honesty, independence, and hard work.41 Originally applied as a class slur, redneck emerged as an affirmation of identity for working-class white men throughout the United States—and even for some middle-class men—in less than a century.

Conclusion

The history of redneck in the American language strikingly demonstrates that words are a powerful force in fashioning class, racial, and ethnic identities. Confronted with an opprobrious epithet and stereotypical images projected onto them by those higher on the social scale, southern white working people reacted pragmatically by seeking not to replace the existing slur redneck but to redefine it to mean an honest, hard-working blue-collar man. In the process they robbed the pejorative stereotypes of much of their damaging psychological impact. Southern white working people’s appreciation for the power of the spoken word was particularly significant since their rural southern folk society was based chiefly on an oral culture in which people transmitted stories, songs, superstitions, home remedies, and humor from one generation to the next. The spoken word was one of only a handful of means available to them with which to socialize their children, inculcate morality and social values, and defend their distinctive lifestyle and culture.42 And their redefinition of redneck has been a process of resistance and empowerment, transforming a slur into a badge of racial, class, and gender identity.

But the story of poor and working-class white southerners is also a tragic one, and much more complex and fraught with contradictions than most historians have generally appreciated. On the one hand, southern white working people were constantly pulled toward a white racial identification and self-defeating racism as in the case of those who joined professional and middle-class white Americans in the Ku Klux Klan during the 1920s. On the other hand, they were also constantly pulled toward class solidarity and biracial labor alliances, as in the example of those who joined Black sharecroppers to organize the integrated Southern Tenant Farmers Union during the 1930s.43

It would be a mistake, however, to see southern white workers as inevitably choosing to identify with either racial or class solidarity, although clearly the history of southern labor organization has been one of racism, white privilege, and Black exclusion. Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the masses of white southerners were—and continue to be—subject to racism and exploitation, albeit in a different sense and to a different degree from African Americans. White workers are at once both perpetrators and products, agents and victims, of that racism because they have so often and so tragically opted for the limited material benefits accorded by their whiteness and, in doing so, have accepted not only their own exploitation and oppression at the hands of employers but have also accepted, as historian David R. Roediger reminds us, “stunted lives for themselves and for those more oppressed than themselves.”44

Patrick Huber is a professor of history and political science at Missouri University of Science and Technology, and the author or editor of five books, including The Hank Williams Reader. He received his PhD from UNC-Chapel Hill.

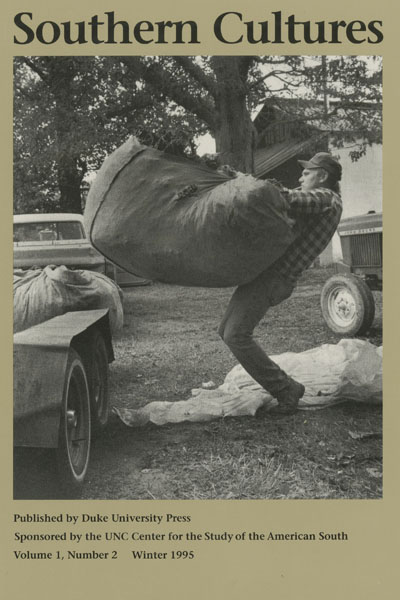

Header image: Billy Carter, brother of 1976 Democratic presidential candidate Jimmy Carter (right), wears a “Redneck Power” t-shirt at a gathering in the Carters’ hometown of Plains, Georgia. Photo by Owen Franken/Corbis via Getty Images.

NOTES

This article was made possible in large part by the rich resource notes on redneck collected by the late Peter Tamony of San Francisco and now housed in the University of MissouriColumbia’s Western Historical Manuscripts Collection. The author wishes to thank, for critical reading, encouragement, and suggestions, Susan Porter Benson, Elaine J. Lawless, John Shelton Reed, Jacquelyn Dowd Hall, Alecia Holland, Karen D. Hayes, Peter Filene, Christine M. Stewart, LeeAnn Whites, Bob Pinson, Ronnie Pugh, Abra Quinn, Meghan Holleran, TimTyson, Lisa J. Yarger, and especially David R. Roediger, Archie Green, and Paul and Midge Huber. An earlier version of this article was presented at the Mid-America Conference on History in Springfield, Missouri, 19-21 September 1991. The epigraph is from Jonathan Daniels, A Southerner Discovers the South (Macmillan Co., 1938), 172-173. This essay has been lightly condensed and updated.

- Wayne Flynt, Dixie’s Forgotten People: The South’s Poor Whites (University of Indiana Press, 1979), 9; Raven I. McDavid Jr., and Virginia McDavid, “Cracker and Hoosier,” Names 21 (September 1973):163; and Lewis M. Killian, “Whites in Northern Cities,” in Charles Reagan Wilson and William Ferris, eds., Encyclopedia of Southern Culture (University of North Carolina Press, 1989), 574-75.

- John R. Silber, “Lyndon Johnson As Teacher,” The Listener 73 (20 May 1965): 730; C. Vann Woodward, “Rednecks, Millionaires and Catfish Farms,” New York Times Book Review, 5 February 1989, 7.

- According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the first known appearance of the term in American print actually dates to 1830, when Anne Newport Royall, a Maryland traveler, reported that Red Necks was “a name bestowed upon the Presbyterians in Fayetteville[,]” North Carolina. Students of the American language have been unable to connect this antebellum Tar Heel usage of the word as a religious slur to its later widespread emergence in the Deep South as a class slur for poor whites. Anne N. Royall, Mrs. Royall’s Southern Tour, or Second Series of the Black Book (1830) quoted in J. A. Simpson and E. S. C. Weiner, eds., Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed., 20 vols. (Oxford, 1989), 13: 422.

- H. A. Shands, Some Peculiarities of Speech in Mississippi (1893) quoted in ibid, 13: 422; J. W. Can, “A List of Words from Northwest Arkansas,” Dialect Notes 2 (1904): 418, 420; the couplet is from a Black worksong collected circa 1920 by Fisk University chemistry professor and amateur folksong scholar Thomas W. Talley and published in Negro Folk Rhymes (Macmillan Co., 1922), 43.

- Hugh Rawson, Wicked Words: A Treasury of Curses, Insults, Put-Downs, and Other Formerly Unprintable Terms from Anglo-Saxon Times to the Present (Crown Publishers, 1989), 326; Robert L. Chapman, ed., New Dictionary of American Slang (Harper & Row, 1986), 318; Ken Johnson, “The Vocabulary of Race,” in Thomas Kochman, ed., Rappin’ and Stylin’ Out: Communication in Urban Black America (University of Illinois Press, 1972), 143.

- “A South Carolinian,” “South Carolina Society,” Atlantic Monthly 39 (June 1877): 680; Billy Bowles and Remer Tyson, They Love a Man in the Country: Saints and Sinners in the South (Peachtree Publishers, 1989), 47.

- Harris quoted in Daniels, A Southerner Discovers the South, 175; and McDonald quoted in Arthur H. Lewis, The Day They Shook the Plum Tree (Harcourt, Brace, & World, 1963), 107.

- William Bradford Huie, Three Lives for Mississippi, with an introduction by Martin Luther King, Jr. (Signet Books, 1968), 62; “Not Everybody Cheers Aaron,” San Francisco Chronicle, 13 April 1973, clipping in the Peter Tamony Collection, Western Historical Manuscripts Collection, University of Missouri-Columbia; and Vaughn quoted in Susan Tucker, Telling Memories Among Southern Women: Domestic Workers and Their Employers in the Segregated South (Schocken Books, 1988), 209. Tucker’s footnote explains that hoo’ger, which is probably related to the southern slur hoosier, is “a slang term that blacks use to refer to a common white, usually a common white woman.”

- On the stereotypical portrayal of rednecks, and poor white southerners generally, in American popular culture, see, for example, Shields Mcllwaine, The Southern Poor-White: From Lubberland to Tobacco Road (Cooper Square Press, 1970 [1939]); Sylvia Jenkins Cook, From Tobacco Road to Route 66: The Southern Poor White in Fiction (University of North Carolina Press, 1976); Jack Temple Kirby, Media-Made Dixie: The South in the American Imagination (Louisiana State University Press, 1978); John Shelton Reed, Southern Folks, Plain & Fancy: Native White Social Types, Mercer University, Lamar Memorial Lectures no. 29 (University of Georgia Press, 1986), 34-47; and F. N. Boney, Southerners All, rev. ed. (Mercer University Press, 1990), 33-38.

- Real estate salesman quoted in V. S. Naipaul, A Turn in the South (Knopf, 1989), 206-208.

- Randy Newman, “Rednecks,” Good Old Boys, Warner Brothers Records; Charlie Daniels Band, “Uneasy Rider,” A Decade of Hits, Epic Records; and Kinky Friedman, “They Ain’t Makin’ Jews Like Jesus Anymore,” Kinky Friedman, ABC Records.

- Jeff Foxworthy, You Might Be a Redneck If . . ., with a foreword by Rodney Dangerfield (Longstreet Press, 1989), 48, 50. See also Jeff Foxworthy, Red Ain’t Dead: ISO More Ways to Tell If You’re a Redneck (Longstreet Press, 1991) and Check Your Neck: More of You Might Be a Redneck If… (Longstreet Press, 1992).

- Isaac quoted in Keith Vacha, Quiet Fire: Memoirs of Older Gay Men, ed. Cassie Damewood (Crossing Press, 1985), 202.

- William Cullen Bryant, Letters of a Traveller; or Notes of Things Seen in Europe and America, 2nd ed. (Putnam, 1850), 358-59.

- Frederick Law Olmsted, The Cotton Kingdom: A Traveller’s Observations on Cotton and Slavery in the American Slave States, ed. Arthur M. Schlesinger (Knopf, 1953), 87.

- For a discussion of the American cultural significance of whiteness and of Blackness, see Winthrop D. Jordan, White Over Black: American Attitudes Toward the Negro, 1550-1812 (University of North Carolina Press, 1968) and David R. Roediger, The Wages of Whiteness: Race and the Making of the American Working Class (Verso Press, 1991); Elizabeth Fox-Genovese, Within the Plantation Household: Black and White Women of the Old South (University of North Carolina Press, 1988), 197; Emily P. Burke, Reminiscences of Georgia (James M. Fitch, 1850) 205; W. E. B. DuBois, Black Reconstruction in America: An Essay Toward a History of the Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860-1880 (Russell & Russell, 1962 [1935J), 700-701.

- Elias Pym Fordham, Personal Narrative of Travels in Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky; and of a Residence in the Illinois Territory: 1817-1818, ed. Frederic Austin Ogg (Arthur H. Clarke Co., 1906), 56.

- Steven Hahn, The Roots of Southern Populism: Yeoman Farmers and the Transformation of the Georgia Upcountry, 1850-1890 (Oxford University Press, 1983), 89-90; Frances Anne Kemble, Journal of a Residence on a Georgian Plantation in 1838-1839, ed. with an introduction by John A. Scott (Knopf, 1961), 182.

- Olmsted, The Cotton Kingdom, 19.

- Kemble, Journal of a Residence on a Georgian Plantation, 110-11; Sidney Andrews, The South Since the War As Shown by Fourteen Weeks of Travel and Observation in Georgia and the Carolinas (Ticknor & Fields, 1866), 177.

- See for example John William De Forest, A Union Officer in the Reconstruction, ed. James H. Croushore and David Morris Potter (Anchon Books, 1968), 157.

- Clare De Graffenried, “The Georgia Cracker in the Cotton Mills,” Century Magazine 41 (February 1891): 488, 490.

- Jacquelyn Dowd Hall, James Leloudis, Robert Korstad, Mary Murphy, Lu Ann Jones, and Christopher B. Daly, Like a Family: The Making of a Southern Cotton Mill World (University of North Carolina Press, 1987), xvi.

- Hall et al., Like a Family, 66-67; I. A. Newby, Plain Folk in the New South: Social Change and Cultural Persistence, 1880-1915 (Louisiana State University Press, 1989), 462-67.

- Newby, Plain Folk in the New South, 465; C. Vann Woodward, Origins of the New South, 1877-1913, A History of the South, ed. Wendell Holmes Stephenson and E. Merton Coulter, vol. 9 (Louisiana State University Press, 1951), 222.

- My discussion of the 1897 strike at the Fulton Bag and Cotton Mills is based on Newby, Plain Folk in the New South, 474-81. Mill workers quoted on pp. 476, 479.

- Chicago Tribune quoted in Albert N. Votaw, “The Hillbillies Invade Chicago,” Harper’s Magazine 216 (February 1958): 64, 66; and 1951 Wayne State University study findings published in Lewis M. Killian, White Southerners (Random House, 1970), 98.

- Strong quoted in Wallace Terry, Bloods: An Oral History ofthe Vietnam War by Black Veterans (Ballantine Books, 1984), 57.

- Jessie Jeffcoat quoted in Tom E. Terrill and Jerrold Hirsch, eds., Such As Us: Southern Voices of the Thirties (University of North Carolina Press, 1978), 61-62.

- Albert D. Kirwan, Revolt of the Rednecks: Mississippi Politics, 1876-1925 (University of Kentucky Press, 1951), 212.

- My discussion in this paragraph and the next is chiefly based on Julian B. Roebuck and Mark Hickson, III, The Southern Redneck: A Phenomenological Class Study (Praeger Press, 1982), v, 3, 65, 80. Rednecks quoted on pp. 64, 106.

- On the Georgia Populists, see Barton C. Shaw, The Wool-Hat Boys: Georgia’s Populist Party (Louisiana State University Press, 1984), 1, 10-11; Roebuck and Hickson, The Southern Redneck, 80 [quotation], 106; and David W. Maurer, “The Lingo of Good-People,” American Speech 10 (February 1935): 19. According to linguist David W. Maurer, the term redneck used to mean “any honest workingman” dates to the turn of the century.

- The Beaver Brothers, “Redneck in the White House,” Scorpion Records, cited in Raymond S. Rodgers, “Images of Rednecks in Country Music: The Lyrical Persona of a Southern Superman,” Journal of Regional Cultures 1 (Fall/Winter 1982): 71; and for examples of President Carter dubbed a “redneck,” see assorted newspaper and magazine clippings in the Tamony Collection.

- One of these photographs of Billy Carter appeared in the San Francisco Examiner, 25 April 1977, clipping in the Tamony Collection; Jeremy Rifkin and Ted Howard, comps., Redneck Power: The Wit and Wisdom of Billy Carter (Bantam Books, 1977); and Billy Carter quoted in Stanley W. Cloud, “A Wry Clown: Billy Carter, 1937-1988,” Time 132 (10 October 1988): 44 [original emphasis].

- Paul Hemphill, “Redneck Chic,” San Francisco Examiner, 7 October 1976, clipping in the Tamony Collection; Richard West, “So You Want To Be A Redneck,” Texas Monthly 2 (August 1974): 57-59; Kathryn Jenson, Redneckin’: A Hell-Raisin’, Foot-Stompin’ Guide to Dancin’, Dippin’ and Doin’ Around in a Gen-U-Wine Country Way (Perigee Books, 1983); Bo Whaley, The Official Redneck Handbook (Rutledge Hill Press, 1987); and Nina Savin, “The Official Redneck Handbook,” Fashion For Men (Fall-Winter 1981): 75-78.

- David Allan Coe, “Longhaired Redneck,” David Allan Coe: Greatest Hits, CBS Records; Vernon Oxford, “Redneck! (The Redneck National Anthem),” Redneck Mothers (various artists), RCA Records; Jerry Reed, “(I’m Just a) Redneck in a Rock and Roll Bar,” Redneck Mothers; Ronnie Milsap, “I’m Just a Redneck at Heart,” Keyed Up, RCA Records; Johnny Russell, “Rednecks, White Socks and Blue Ribbon Beer,” Redneck Mothers; and The Charlie Daniels Band, “(What This World Needs Is) A Few More Rednecks,” Simple Man, Epic Records.

- Elton John, “Texan Love Song,” Don’t Shoot Me I’m Only The Piano Player, MCA Records; Jan Reid, The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock (Heidelberg Press, 1974); Archie Green, “Austin’s Cosmic Cowboys: Words in Collision,” in Richard Bauman and Roger D. Abrahams, eds., “And Other Neighborly Names”: Social Process and Cultural Images in Texas Folklore (University of Texas Press, 1981), 162-63; and Joe Nick Patoski, “Southern Rock,” in Jim Miller, ed., The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock & Roll (Random House, 1980), 357-59.

- F. N. Boney, “The Redneck,” Georgia Review 25 (Fall 1971): 336; Randy Howard, “All-American Redneck,” Warner Brothers Records; John Schneider, “A Redneck Is the Backbone of America,” MCA Records; Roebuck and Hickson, The Southern Redneck, v, 80; for female derivatives of the term, see Sharon McKern, Redneck Mothers, Good Ol’ Girls and Other Southern Belles: A Celebration of the Women of Dixie (Viking Press, 1979), and The Bellamy Brothers, “Redneck Girl,” The Bellamy Brothers Greatest Hits, vol. 1, MCA/Curb Records.

- Lowe quoted in John Balzar, “A Loquacious Redneck,” San Francisco Chronicle, 22 October 1977, clipping in the Tamony Collection; rednecks quoted in Roebuck and Hickson, The Southern Redneck, 65; and real estate salesman quoted in Naipaul, A Turn in the South, 209.

- BiI Dwyer, How Tuh Live In The Kooky South: A Fun Guide Book Fer Yankees (Merry Mountaineers Publication, 1978), 22.

- Daniels, Southerner Discovers the South, 183; and Roebuck and Hickson, The Southern Redneck, 80, 93-98. Redneck quoted on p. 64.

- See Elliott J. Gorn, “Gouge and Bite, Pull Hair and Scratch: The Social Significance of Fighting in the Southern Backcountry,” American Historical Review 90 (February 1985): 27-28.

- David R. Roediger, “Gaining a Hearing for Black-White Unity: Covington Hall and the Complexities of Race, Gender and Class,” in Towards the Abolition of Whiteness: Essays on Race, Politics, and Working Class History (Verso Press, 1994), 134-39.

- Roediger, The Wages of Whiteness, 13.