“Call this a first draft of tomorrow’s history of today’s South—one that places the coast at the center of the story and seeks to understand how beaches came to reflect and influence broader changes in the region’s cultures and political economy.”

“And everyone that heareth these sayings of mine, and doeth them not, shall be likened unto a foolish man, which built his house upon the sand. And the rain descended, and the floods came, and the winds blew, and beat upon that house, and it fell, and great was the fall of it.” —Matthew 7:26–27

In October 2005, less than two months after Hurricane Katrina laid waste to the Gulf Coast and as hundreds of thousands of Mississippians remained homeless, the Mississippi state legislature assembled a special session. At the urging of Harrah’s Entertainment and other major players in the gaming industry, the state rushed through legislation that permitted the construction of inland mega-resorts, deemed of critical importance for the state’s recovery. The move was an indicator of what Mississippi would prioritize over the next decade. While efforts to aid displaced low-income homeowners languished, federal and state assistance for the multi-billion dollar casino industry continued to flow. In 2008, the Department of Housing and Urban Development approved a plan by state officials to divert $600 million in emergency federal aid for low-income housing to support Gulfport’s growing casino and cruise ship industries. (Congress had already lowered the required amount of $5 billion in federal aid devoted to low- and moderate-income housing from 70 to 50 percent.) Thus, the Gulf coast’s casinos have roared back with a vengeance, while low-income coastal residents still struggle to rebuild their lives and find a place in a new coastal economy.1

Stories of destruction, displacement, and transformation are written along the shorelines of today’s American South.

Similar stories of destruction, displacement, and transformation are written along the shorelines of today’s American South, as are signs of the damaging, ironic, and (for future generations) catastrophic results of mid-twentieth-century Americans’ rush to the seashore, and their insatiable desire to contain it. Over the second half of the twentieth century, an army of engineers, developers, and promoters turned fragile ribbons of sand into real estate, and formerly remote, desolate, and sparsely populated shores into vibrant leisure and tourism economies.

This recent trend has important implications for the future. Conservative estimates foresee sea levels rising anywhere from twenty to eighty inches over the next century. Today, nearly 5 million Americans live in 2.6 million homes located at less than four feet above high tide. Many portions of the coast most vulnerable to rising seas are located in the South, as are most of the nation’s fastest growing coastal counties. While many Americans struggle to make mortgage payments on homes that are figuratively “underwater,” at the close of the twenty-first century we can expect to see entire coastal communities (and with them, coastal economies) literally drowned.2

Our relationship with land and water will undergo dramatic changes.

A threat to human civilization, global climate change promises not merely to transform the nature of geopolitics in the twenty-first century, but along with it, our sense of the past. While policymakers scramble to mitigate the cataclysmic effects of rising sea levels, historians work to unravel the tangled knot of public policies and social and cultural changes that led to the concentration of so many American people—and the investment of so much American capital—so dangerously close to the sea. To date, however, the overdevelopment of the South’s coastlines is matched by the underdevelopment of its study. As future generations are forced to come to terms with the effects of climate change, the rampant development and environmental engineering of coastlines, and the reckless and unsustainable exploitation of precious water resources will, in all likelihood, come to occupy a place alongside racial moderation, economic modernization, and political realignment as one of the most important developments in the South over the past fifty years.

Call this a first draft of tomorrow’s history of today’s South—one that places the coast at the center of the story and seeks to understand how beaches came to reflect and influence broader changes in the region’s cultures and political economy. Sifting through these sands, we find a past whose lessons will become ever more important as our relationship with land and water undergoes dramatic changes in the decades ahead.

From Cotton Belt to Sunbelt

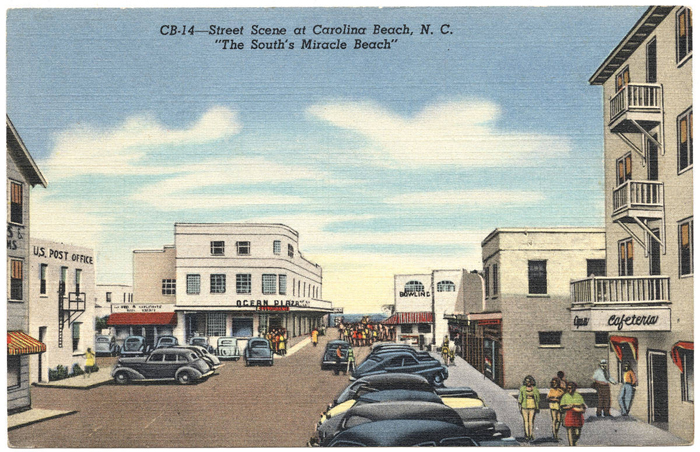

At the turn of the twentieth century, much of the coastal South was considered wild and unruly—marginal to the region’s agriculture-based economy. Shorelines were the South’s most forsaken and forgotten lands, subject to violent storms, and home to predatory animals, dense forests, and sandy, non-arable soil. But by the mid-twentieth century, such land had become home to some of the nation’s hottest real estate markets, attracting a flood of vacationers, retirees, and second-home owners, and initiating a transformation in the nation’s political and economic geography that continues to this day. The land’s dramatic shift into a seemingly endless string of hotels, golf courses, vacation homes, and time-share resorts, which are annually subject to the furies of the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico, and the emergence of leisure industries and real estate development as a key sector of the South’s modern economy, parallels the South’s broader transformation from “cotton belt to Sunbelt,” and from the nation’s “number one economic problem” to its fastest growing and most dynamic region. This road to prosperity was paved with federal dollars—in the form of military spending and transportation, and infrastructure development—and gave rise to a new class of pro-growth southern politicians who successfully attracted business and industry with generous tax breaks, anti-labor laws, and lax environmental regulations. Historian Bruce Schulman has argued that by the 1970s, the South exerted a “magnetic power” over the nation’s people and economy.3

Few parts of the South had a stronger magnetic pull than its coastlines, and few places benefitted more from the power of an activist state to fuel the growth and development of private industry. Federal policies and agencies, in particular, the Army Corps of Engineers, made the settlement and development of coastal areas both possible and profitable by manufacturing white sand beaches and providing incentives for wealthy and upper-middle-class Americans to relocate or build second homes by the sea. As coastal engineers and promoters fed beaches with sand borrowed from inland lagoons or the continental shelf, they also nourished a distinct political culture.4

Examining southern history from its shores forces us to re-evaluate the role of race in the making of the Sunbelt, as well as the Sunbelt’s effects on the South’s African American population. Recent scholarship often connects the Sunbelt’s rise to Jim Crow’s demise, as racial terrorism that sustained the region’s agricultural and political economy became more of a liability than an asset in promoting a pro-growth and corporate-friendly image of the region. The booming economy of the past several decades, we have been led to believe, merely skipped over those parts of the South with large black populations, leaving most African Americans on the outside looking in at new-found prosperity. But the same could not be said of the coastal South, which was home to substantial numbers of black landowners. The steady erosion of their land-base was not incidental, but fundamental, to the creation of modern coastal economies. In places like Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, architects of the coastal South gained their wealth by engaging in various forms of legal chicanery and economic exploitation to claim the one asset African Americans possessed in relative abundance: land. In the process, developers displaced families, disintegrated communities, and dismantled the economic foundations that blacks struggled to build under Jim Crow. Clearly, the Sunbelt did not bypass the black South; it plowed over it.5

Just as coastal developers struggled in vain to draw property lines along shorelines whose shape changed with the seasons, for the historian of the coastal South, lines that divide the Jim Crow from the Sunbelt eras are fluid and far more devastating to certain segments of the black population than previously recognized. In places like the South Carolina Sea Islands, black residents under Jim Crow struggled to secure a degree of autonomy and independence from the exploitative labor relations that characterized the region as a whole, while the decades following World War II were a time of great upheaval and wholesale dispossession, as speculators and developers descended onto formerly forsaken shores.

As early as the 1880s, some features of the coastal Sunbelt began to come into focus. Spurred by the extension of railroad lines into South Florida, planners developed new techniques for turning wetlands into real estate, while promoters honed new tactics for attracting vacationers and investors. This made apparent the folly of seaside development, as normal coastal processes of erosion and accretion made a mockery of newly drawn property lines, and damaging (yet highly predictable) storms claimed lives and washed buildings and personal savings out to sea. Some of the deadliest hurricanes of the late nineteenth century made landfall at southern coastal resorts, including 1893’s Chenniere Caminada storm, which killed nearly 800 people at the Grand Isle resort off the coast of Louisiana.6

Such devastation did not hasten a retreat from the beach. Instead, it led to louder and more sustained calls for states to invest in the protection of coastal people and property. For instance, 1926 saw the formation of the American Shore and Beach Preservation Association, an organization dedicated to lobbying local, state, and federal governments to adopt measures for protecting beaches and (more to the point) beachfront properties. The emerging field of coastal science and the publication of a spate of studies that claimed that coastal settlements could be protected through the construction of seawalls and other hard stabilization measures furthered efforts.

To read this piece in full, access it via Project Muse or purchase Southern Cultures, Vol. 20, No. 3: Southern Waters, in our online store.

Andrew W. Kahrl is Associate Professor of History and African American and African Studies at the University of Virginia and author of The Land Was Ours: African American Beaches from Jim Crow to the Sunbelt South (Harvard University Press, 2012).Header image: Aerial view of Herbert C. Bonner Bridge, Oregon Inlet, NC, 2009. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.NOTES

1. “Mississippi Governor Signs Bill to Rebuild Gulf Casinos on Land,” New York Times, October 18, 2005.

2. “Surging Seas: Sea Level Rise Analysis by Climate Central,” Climate Control, accessed April 30, 2014, http://sealevel.climatecentral.org. See also Andrew L. Jones and Michael R. Phillips, Disappearing Destinations: Climate Change and Future Challenges for Coastal Tourism (Cambridge, UK: CABI, 2011).

3. Bruce Schulman, From Cotton Belt to Sunbelt: Federal Policy, Economic Development, and the Transformation of the South, 1938–1980 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1994).

4. Orrin H. Pilkey, The Corps and the Shore (Washington, D.C.: Island Press, 1996).

5. See Matthew D. Lassiter, The Silent Majority: Suburban Politics in the Sunbelt South (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006).

6. Rose C. Falls, Cheniere Caminada, or, The Wind of Death: The Story of the Storm in Louisiana (New Orleans, 1893).