While researching his 1885 biography of Edgar Allan Poe for Houghton Mifflin’s American Men of Letters series, George E. Woodberry discovered that Poe had enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1827 under the name of Edgar Perry. As is now well known, Poe was shipped to Sullivan’s Island, South Carolina, a barrier island on Charleston Harbor, where he was stationed from November 1827 until December 1828. His company was then transferred to Fortress Monroe in Point Comfort, Virginia, where Poe was promoted to Sergeant Major before arranging a substitute and being discharged in April 1829. Poe had deliberately hidden his Army stint—and along with it, his year on Sullivan’s Island—instead fabricating stories of foreign adventure in Greece and Russia to account for these years in biographical sketches that appeared during his lifetime. But suddenly, thirty-six years after Poe’s death, South Carolina could, in some small measure, claim him, along with Boston, Richmond, Charlottesville, West Point, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York. This essay explores the efforts of Charleston and Sullivan’s Island to write Poe into their cultural history without the benefit of detailed documentary evidence of his activities there. As Poe’s biography began to absorb the year spent on Sullivan’s Island, what did it mean for the Carolina Lowcountry to include Poe in its history? What might the city and nearby barrier island have contributed to Poe’s imagination? What would it mean to call Poe a “Charleston writer”?

The fact that Poe set his 1843 story “The Gold-Bug”—one of his most celebrated tales, and the one for which he received a much-needed $100 prize—on and around Sullivan’s Island should give the small town and nearby Charleston bragging rights among Poe places. There is no Poe story with an equivalent emphasis on place set in the American cities where he spent considerably more time. Poe describes the area at some length, referring to Charleston, where the narrator resides, three times in the opening pages. Moreover, the protagonist Legrand’s discovery of a treasure buried by Captain Kidd depends on his ability to project clues left by Kidd onto the landscape of the island and the terrain of the “wild and desolate” mainland nearby. And yet, little in the descriptions would have required an intimate knowledge of the area; Poe describes a typical southeastern barrier island, narrow and sandy with low-lying sweet myrtle and palmetto. Later in the story, Poe conspicuously alters the landscape by placing steep hills on the mainland coast:

It was a species of table land, near the summit of an almost inaccessible hill, densely wooded from base to pinnacle, and interspersed with deep crags that appeared to lie loosely upon the soil, and in many cases were prevented from precipitating themselves on the valleys below, merely by support of the trees against which they reclined. Deep ravines, in various directions, gave an air of still sterner solemnity to the scene.1

While Poe undoubtedly drew upon his memory of Sullivan’s Island for “The Gold-Bug,” after fifteen years, he might not have recalled the island vividly, and didn’t need to for the purposes of the story, which required a piece of high ground on which to bury treasure more than it did an accurate description of the island and the marshy terrain between Charleston Harbor and what is now the Intracoastal Waterway. There would be no more reason to assume that Poe had firsthand knowledge of Sullivan’s Island or Charleston than there would be that he had spent time in Paris, the setting for the Dupin mysteries, or the Antarctic, the setting for the conclusion of The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym.2

While few Charlestonians seem to have noticed their newly discovered connection to Poe immediately following Woodberry’s discovery in 1885, Poe’s broader southern credentials were bolstered around the same time by guidebooks to American literary history, stage melodramas, and ceremonies honoring him on the fiftieth anniversary of his death (1899) and centennial of his birth (1909). Books ranging from Walter Bronson’s Short History of America in Literature (1900) to Reuben Post Halleck’s The Spirit of American Literature (1911) to LaSalle Corbell Pickett’s Literary Hearthstones of Dixie (1912) presented Poe as a distinctly southern writer. Moreover, Woodberry included Poe in the chapter on southern writers in his guidebook America in Literature (1903), and his revised biography of 1909 placed new emphasis on Poe’s southern background. Around the same time, several biographical plays, notably George Hazleton’s The Raven, depicted Poe as a southern gentleman tragically displaced in a hostile northern climate. Speakers at the 1899 and 1909 ceremonies in Charlottesville repeatedly invoked Poe’s southern roots. “More than anyone else,” declared Citadel professor St. James Cummings at the Charlottesville centennial ceremony, “Poe represents the South.” Meanwhile, in Richmond, where four Confederate Generals were memorialized on Monument Avenue between 1890 and 1919, Poe enthusiasts established the Poe Shrine (now the Poe Museum) in 1922.3

At the same time, this Southern Poe was adopted as a spiritual forbear by a group of Charlestonians seeking to create a literary and cultural renaissance through institutions such as the Charleston Museum and the Poetry Society of South Carolina. In 1922, John Bennett, the elder statesman of the group, wrote an article on Poe for the Columbia, South Carolina daily The State and contributed to the fundraising effort for the Richmond Poe Shrine. That same year, DuBose Heyward (best known for the novel Porgy and subsequent collaboration with George and Ira Gershwin on Porgy and Bess) and poet-novelist Hervey Allen highlighted Poe’s Charleston connection in a guest-edited issue of Poetry magazine, and each wrote a poem in tribute to Poe for their co-authored collection Carolina Chansons: Legends of the Lowcountry. Heyward’s poem looks like Poe’s “For Annie” or “Eldorado” on the page, with short, six-line stanzas, but he establishes a less regular, almost bluesy, rhythm as he describes a walk with Poe on Sullivan’s Island:

Once in the starlight

When the tides were low,

And the surf fell sobbing

To the undertow,

I trod the windless dunes

Alone with Edgar Poe (lines 1–6).4

The opening stanzas emphasize elements of the setting that would have been familiar to Poe in 1828, as well as to Heyward in 1922—surf and dunes, “myrtle thickets” (9), and “clustered windows / Of the barrack-room” (11–12). But in the fourth stanza, the speaker enters another world in Poe’s company:

Life closed behind us

Like a swinging gate,

Leaving us unfettered

And emancipate . . . (19–22).

For that stanza and the three that follow, Poe and the speaker transcend space and time, as references to local setting are replaced with a night “Seething with its planets” and “Showing us infinity” (27, 29). If, as so many readers of Poe’s poetry have felt, his goal is to provide momentary access to an aesthetic, spiritual realm beyond time and science’s “dull realities,” that is exactly what the speaker of this poem experiences in Poe’s presence. Together they hear “the many things / Silence has to say” (37–38), apprehending what is always there but inaccessible to mere mortals. Poe, the Romantic artist, suffers in his effort to translate these mystical experiences: he “Raised his face, and there / Shone the agony that those / Loved of God must bear” (34–36). And when, with the final two stanzas, the night and its dream-vision ends, the local details return with “the bugle’s silver,” but the speaker feels “Like a man new born” (48) from his encounter with the great poet. He closes by reminding us again of the pain that underlies Poe’s gift:

But my friend and master,

Heavy-limbed and spent,

Turned, as one must turn at last

From the sacrament;

And his eyes were deep with God’s

Burning discontent (49–54).

If Poe is returning to the fort, then his burning discontent is that of a visionary trapped in the dull routine of army life; at the same time, the sense of nobility and suppressed anger in the face of suffering, along with the pursuit of supposedly higher ideals, suggests a Lost Cause mythology that lurked in the background of the Charleston Renaissance. Heyward makes no overt connection between Poe and Confederate Charleston—after all, Poe died over a decade before the first shots of the Civil War. Yet it is worth noting that his walk with Poe’s ghost would have included a moonlit view of nearby Fort Sumter, on which construction began the year after Poe’s company left South Carolina.

Hervey Allen’s poem “Alchemy” similarly depicts Poe as a Romantic outcast; he, too, situates the poet/speaker on Sullivan’s Island, not meeting Poe but dreaming of his return. Like Charles Baudelaire’s 1861 poem “The Albatross,” which casts the Poe-esque artist as a bird who hobbles on land, the opening lines of “Alchemy” explain that “Some souls are strangers in this bourne; / Beauty is born of their discontent.” Because these souls are “exiles” from another planet, they recast what they see on Earth through their “memories of other stars” (8). In the second stanza, Allen’s speaker claims that “this island beach where Poe once walked” is one of the

favored spots

Where all earth’s moods conspire to make a show

Of things to be transmuted into beauty

By alchemic minds (12–16).

The speaker wonders if the bells and chimes from the city across the harbor, sounds that must have inspired Poe, might “call him back / To walk upon this magic beach again” (24–25). Allen imagines Poe in full gothic regalia, “heralded by ravens” and “Wrapped in a dark cape” (27, 29). His speaker longs for the walk on the beach that takes place in Heyward’s poem: “And he will speak to me / Of archipelagoes forgot, / Atolls in sailless seas, where dreams have married thought” (31–33).

Both poets, then, argue that Poe’s time on Sullivan’s Island had a profound effect on him, so much that he still walks along the beach. Or, interpreting the poems less literally, Heyward and Allen suggest that Sullivan’s Island evokes Poe, that the poet and the place share a mystical, dreamlike beauty “born of discontent.” Furthermore, they implicitly claim to have inherited a place-based literary tradition from the poet who haunts the beach they walk.

A third poem by a member of the Charleston Renaissance circle, Beatrice Witte Ravenel’s “Poe’s Mother” (1925), claims Poe for Charleston through less direct but no less insistent means. More ambitious than “Edgar Allan Poe” or “Alchemy,” this 200-line blank verse poem is voiced by the itinerant actress Eliza Poe, while in Charleston in April 1811—pregnant with her third child Rosalie, suffering from tuberculosis, reflecting on her marriage, her career, and her precocious two-year-old son. While relatively little of the poem refers directly to Edgar, Ravenel imbues Eliza with a sensibility familiar to readers of her son’s poetry. It begins,

It’s something to be born at sea, as I

Was born. Earth fails to get full clutch on you.

You keep a certain cleanliness of depths—

Soul, self-respect, you call it what you like.5

Eliza’s opening lines recall Poe’s early Romantic poetry, in which he presents himself as detached from normal, waking life, profoundly alone, seeking artistic integrity above all else, what David Ketterer, in The Rationale of Deception in Poe, refers to as “arabesque reality.” Like Heyward and Allen, Ravenel invokes the impulse Poe expressed in his early poetry, and Eliza’s monologue takes place, appropriately, in the arabesque of early morning hours, whose liminality and beauty appeal to her: “This is the hour / I love, the unrealest hour of all the day” (21–22). Later she reminds herself, “Let me get the good / Of these two unreal hours. Let me be quiet. / The only bearable things in life are dreams” (69–70).6

Eliza refers directly to her illness only twice—in the lines above and in a more hopeful earlier reference, “My cough itself grows better in this air” (29)—but mortality is clearly on her mind, as she recalls having played the part of Juliet two years earlier, in Boston, when Edgar was born:

Juliet, the girl whom everybody loves.

Why has the world conspired to clothe its dream

Of utter beauty in a velvet pall,

With pallid velvet tapers, head and feet,

In Capulet’s monument? (44–48).

Perhaps it is because, as her son would later write, “the death . . . of a beautiful woman is, unquestionably, the most poetical topic in the world.” She sees that her child is already death-haunted, or at least the inheritor of his mother’s offstage and onstage tragedies:

I almost could believe God threw His shadows

Across my skies and worked my cloudy ferment

To shape this child.

He’s born of Juliet’s body! (117).7

In Poe’s 1831 poem “Israfel,” the speaker envies an angelic musician’s artistic power:

If I did dwell where Israfel

Hath dwelt, and he where I,

He would not sing one half as well—

One half as passionately,

And a stormier note than this would swell

From my lyre within the sky (39-41).8

Similarly, Ravenel’s Eliza expresses frustration as she longs for transcendence: “All, all my life I’ve wanted the next highest / To feel myself dragged back—the silver chains / Of seas, or jet-black chains of this vile earth!” (183–85). Earlier in the poem, she had noticed Edgar gazing at the figure of a lyre wrought into the iron balcony, a possible allusion to “Israfel.” And she recognizes that even at the age of two, he insists on beauty over truth, as he “holds me off even while he clings to me, / His fingers on my mouth: ‘Sing, sing—not talk!’” (120–21). As the poem concludes, Edgar wakes, crying, and Eliza tries to comfort him, as Ravenel alludes to Poe poems—“The City in the Sea,” “Fairy Land”— that might have been inspired, however indirectly, by the Lowcountry environment:

She’ll sing [Eliza says of herself]

Of cities in the water, just like this,

And flowers that bloom when everyone’s asleep;

And he shall watch the steeples, and the point

Of that long heaving island, and the sunrise

That catches every color on the marsh.

She’ll make the whole world pretty for him! Yes—

We’ll sing—not talk . . . we’ll sing . . . (194–201).

While Ravenel’s poem is more subtle than Heyward’s and Allen’s in advertising its Carolina Lowcountry setting, those last lines clearly suggest that Poe’s earliest memories of beauty might be attached to this place: the lyre in the wrought-iron balcony, a city nearly in the sea, the beautiful sunrise over a cityscape dotted with steeples, even his mother’s voice singing, not talking, of these sights. Moreover, all three poems strongly imply that the Lowcountry’s languid natural rhythms and otherworldly beauty inspired a poet known for valorizing dream states and disdaining mundane reality, situating Poe on a spectrum of southern dreamers that would eventually include fictional characters such as Ashley Wilkes and Blanche DuBois. Louis D. Rubin, in his introduction to a 1969 edition of Ravenel’s poems, reports that “Poe’s Mother” “was frequently reprinted in anthologies during the 1920s and was widely admired,” and so must have helped popularize, among Charlestonians, the idea of an intimate link between Poe’s aesthetics and Charleston’s ambiance.9

That link was further promoted by a small diorama installed at the Charleston Museum in 1923, consisting of a wax figure of Poe sculpted by Dwight Franklin, standing on the beach at Sullivan’s Island. Allen, Heyward, and John Bennett spoke at the unveiling, which, according to the Year Book of the Poetry Society of South Carolina, attracted a “thronging attendance, which sat on the chairs, floors, platforms, benches, overflowed from the Children’s Room into the Reading Lobby; many indeed were turned away.” The diorama focused on the statuette of Poe, about one foot in height, in military dress, including a long, windblown black cape. In the eyes of the Poetry Society, the installation placed Charleston alongside other cities with strong claims to Poe’s legacy: “The square, renamed by a forgetful Boston, the tragic cottage at Fordham, the Old Stone House in Richmond [site of the Poe Shrine], and the miniature landscape statuette of Edgar Poe, in Charleston, these are the memorials to him of recent recognition.” Not surprisingly, the plaque that accompanied the diorama lay claim to the landscape’s influence on Poe: “The semi-tropical scenery of the Carolina coast, its palmetto covered dunes, dark jungle pools, and deep bird-haunted swamps provided the landscape setting which Poe’s imagination transmuted into the very spirit of much of his poetry and prose.”10

But the most substantial monument to Poe produced by the Charleston Literary Renaissance came in 1926, with Hervey Allen’s Israfel: The Life and Times of Edgar Allan Poe, a richly detailed, if not completely accurate, interpretive biography. Allen’s title alludes to the poem that seems to have impressed the Charleston Renaissance writers with its image of the artist caught between angelic aspirations and earthly realities; not surprisingly, he devoted an entire chapter to “Israfel in Carolina.” “Out of the strange and impressive environment into which he was about to be plunged for a year,” he writes, “came directly much of his material for The Gold-Bug, The Oblong Box, The Man that Was Used Up, The Balloon Hoax, and bits of the melancholy scenery, and sea and light effects which, from the time of his sojourn in Carolina, haunt so much of his poetry.” Allen argues, briefly, that Poe’s increased use of “exotic” sources in his second and third volumes of poetry stem from the “peculiar nature” of the Lowcountry landscape (171). What was it about Sullivan’s Island that would have influenced Poe in this way? According to Allen, “The one overpowering impression of the place is the continual bell-like breaking of the ‘sounding sea,’ the eye-puckering glare of the lime-white sun, and the dirge of the wind through the myrtles, accompanied by a faint, clacking sound like an overtone of eery applause caused by the clapping together of the palms of the palmettos” (172).11

Allen doesn’t specify exactly how these sights and sounds would have affected Poe, but one might presume that “The Bells,” written two decades after his year on Sullivan’s Island, is the poem that echoes the “bell-like” breaking of waves, while the wind’s dirge perhaps instilled Poe with the strain of melancholy or the macabre for which he was later known. While most of the chapter is devoted to “The Gold-Bug,” Allen also links Poe’s fictional house of Usher to “some old, crumbling and cracked-walled colonial mansion found moldering in the Carolina woods,” and his poem “The Sleeper” to “the great family tombs on the plantations about Charleston” (179). In short, with little documentary evidence to use in constructing this chapter, Allen recreated the landscape in Poe’s image, making the strongest case he could for the lasting effects of Poe’s year on Sullivan’s Island.

In the wake of Allen’s biography, scholars uncovered new information and made further conjectures regarding Poe’s experience in the Lowcountry. In 1934 W. Stanley Hoole published a note providing the name of the ship—the Waltham—that carried Poe’s company to Charleston, as well as the date of arrival. Ten years later, Hoole speculated on Poe’s visits to Charleston in an essay entitled “Poet in Uniform”: “As a coast-guardsman in an isolated post, he had time on his hands to roam the island, swim in the warm surf, visit the city’s libraries, and to attend the Charleston Theatre where his father . . . had starred as ‘The Lover’ in The Old Soldier and his mother, as a member of a traveling troupe sixteen years before, had played ‘Jacintha’ opposite the famous John H. Dwyer’s ‘Ranger’ in The Suspicious Husband.” While researching his monumental 1941 Poe biography, Arthur Hobson Quinn corresponded with Dr. William Drayton Jr., of Charleston, who affirmed that Colonel William Drayton, to whom Poe’s Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque was dedicated, “made warm friends” with the young poet in 1828. Quinn also noted that a local “conchologist of distinction,” Dr. Edmund Ravenel, lived on Sullivan’s Island while Poe was stationed there, and he imagined a friendship between the two men that might have influenced Poe’s decision to collaborate with Thomas Wyatt on The Conchologist’s First Book (1839) as well as the creation of the Legrand character in “The Gold-Bug.” Further speculation about Poe’s activities came from Robert Adger Law, who, in 1934, discovered a possible source for “Annabel Lee” in the Charleston Courier from 1807. Had Poe known enough of his parents’ lives to search the Courier’s files for more information? And in the process had he discovered the poem entitled “The Mourner,” which bears undeniable resemblance to “Annabel Lee”?

With my Anna I past the mild summer of love

‘Till death gave his cruel decree,

And bore the dear angel to regions above

From the cot by the side of the sea!12

These discoveries and theories seem to have fueled local legend by the mid twentieth century. Or perhaps it’s just coincidence—but I have learned that if I ask anyone who grew up in Charleston what they know about Poe’s connection to the city, there is at least a 50 percent chance that they will reply that “Annabel Lee” is about a young woman Poe met when he was stationed at Fort Moultrie. This urban legend made its way into print in 1969, when the Tradd Street Press in Charleston issued an edition of “The Gold-Bug” with illustrations by local artist Elizabeth O’Neill Verner, an introduction by University of South Carolina professor Frank Durham, and a postscript by Verner’s daughter Elizabeth Verner Hamilton. Durham’s introduction carefully repeated the findings of Allen and Quinn but hedged on any speculation about Poe’s activities in Charleston. Hamilton’s postscript, however, reprinted a recently published letter to the daily News and Courier by C. T. Leland, who argued that “by making Charleston an historical shrine the old and rarely seen parts of the city can be publicized to lucrative advantage. For example, Edgar Allan Poe’s great love, Annabel Lee, certainly lived at Sullivan’s Island, the ‘Kingdom by the Sea’ and is probably buried not too far from Fort Moultrie. If this site is discovered, it can play a role as important as the tomb of Romeo and Juliet at Verona which attracts over half a million visitors each year.”13

Hamilton reports that she “sent the letter to Professor Durham and received word, ‘Annabel Lee is moonshine.’” But then, after reading “Annabel Lee,” she decided to pursue the matter further, and concluded that Annabel Lee’s “highborn kinsmen” must be members of the Ravenel family, given the fact that Edmund Ravenel lived on Sullivan’s Island and was a highborn Charlestonian. She consulted a College of Charleston classics professor, Alexander Lenard, whom she believed had encouraged his student Caroline (C. T.) Leland to write the letter. “He twinkled and said ‘I found a tombstone in a mossy cemetery. A wonderful trysting place for lovers. I’ll draw you a map.’” Caroline Leland delivered the map to Hamilton, who published it in her postscript to the paperback edition of “The Gold-Bug,” which became a popular local souvenir. The map is tiny, sketchy, and almost impossible to read, but it indicates that a tombstone with the initials ALR can be found in the churchyard of the Unitarian Church in Charleston: Annabel Lee Requiescat, according to Lenard; Annabel Lee Ravenel, suggests Hamilton. She concludes, “Annabel Lee may be pure moonshine, but where does the moon shine brighter than on Sullivan’s Island? Ask any young lovers.”14

While the notion of a Charlestonian Annabel Lee might predate the Tradd Street Press “Gold-Bug” (Durham’s dismissive “Annabel Lee is moonshine” sounds like it comes from someone who has heard it before), this publication certainly gave new life to whatever smattering of legends might have existed before. In a phone interview, Leland cheerfully confirmed that she and Lenard conspired to spread the story by means of her letter to the editor, amused by the idea of tourists visiting the grave of Annabel Lee. She remained amused at the persistence of the legend, and reported regularly hearing carriage tour guides telling customers that Annabel Lee was buried in the Unitarian Churchyard. Meanwhile, the legend continues to spread—and mutate—by way of websites and blogs devoted to ghost stories and Charleston lore. In one version, related on gothichorrorstories.com and ghostsource.com, the story of Annabel Lee’s thwarted love affair and tragic death was a pre-existing local legend, but because “Poe is known to have haunted both the beaches of Sullivan’s Island, as well as the taverns of Charleston,” he must have heard the story and based his famous poem on it—over twenty years later (“Annabel Lee” was written in 1849). The blog for a Charleston hotel, the Elliott House Inn, embellishes the plot with Annabel’s father locking her in her room, chasing Poe from the house, and, after her death, removing headstones from the cemetery so that Poe could never find her. While acknowledging the lack of evidence for the legend, the Inn’s blogger suggests that by reading the poem, “you can see how the legend may have some truth.”15

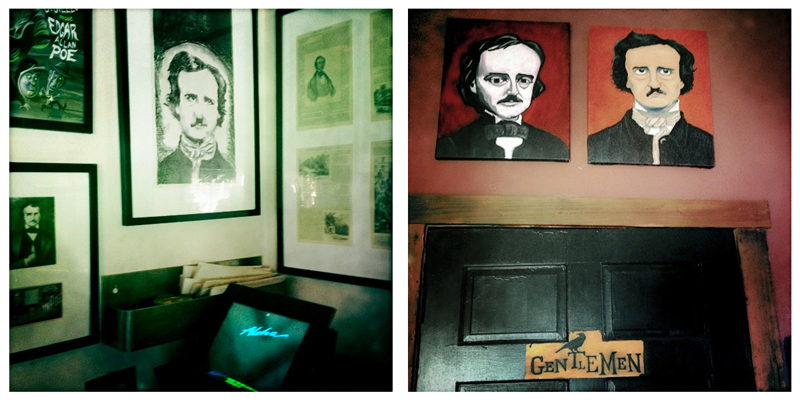

Recent commercial ventures have made Poe more visible in the Lowcountry than ever. The décor of Poe’s Tavern, which opened in April 2003 on Sullivan’s Island, includes a mural of Poe painted on the fireplace and classic Poe-themed advertisements and movie posters. The brooding images of Poe haunting a beachside bar might seem incongruous at first, but particularly on the rare occasions when the restaurant isn’t overcrowded, the combination resonates with the poems by Allen and Heyward: the Sullivan’s Island Poe is a pensive beachcomber, not the harried, combative editor/journalist known to Philadelphia, New York, and Baltimore. To the same end, the East Cooper Outboard Motor Club rents an event facility, especially popular for oyster roasts, known as “Gold Bug Island,” on land that corresponds to the site where the pirate treasure is discovered in Poe’s story. The theater company Charleston Stage—whose home base is the Dock Street Theater, a building that served as a hotel when Eliza Poe and, perhaps, Private Edgar Perry visited the city—includes in its repertoire a Poe-themed play titled Nevermore!, written by the company’s founder Julian Wiles. The central plot places Poe on a ghost ship, where Satan tortures him with devices from his own stories in an effort to acquire his soul. Poe is rescued, however, by none other than Annabel Lee, the Charleston belle he fell in love with while stationed at Fort Moultrie. As a final example, from 2005 to 2011, Fort Moultrie hosted a Halloween-season event, Poe: Back from the Grave, produced by a Charleston nonprofit arts organization, featuring local actors performing adaptations of Poe’s work in various locations throughout the fort. The press release for the 2009 production began, “‘I was a child and she was a child in this kingdom by the sea . . .’ says the memorable poem ‘Annabelle Lee’ [sic] by Edgar Allan Poe. Many believe it was written about Sullivan’s Island when Poe was stationed at Fort Moultrie.” Performances of “Annabel Lee,” “The Raven,” and selected Poe stories made effective use of the fort, particularly the dungeon-like powder magazines’ damp, claustrophobic atmosphere and echo-chamber acoustics. While it is unlikely that anyone learned much about Poe at Poe: Back from the Grave, the event provided an opportunity to celebrate something—an image, an idea—called Poe, that Charlestonians and Sullivan’s Islanders now regard as part of their history.

On the first page of Pat Conroy’s novel The Lords of Discipline (1980), Will McLean, the narrator, describes Charleston as “a dark city, a melancholy city, whose severe covenants and secrets are as powerful and beguiling as its elegance, whose demons dance their alley dances and compose their malign hymns to the side of the moon I cannot see.” He then identifies himself with Poe, on the grounds that neither of them was “a son of Charleston” but both spent a transformative period of their lives there:

I like to think of him walking the streets of Charleston as I walked them, and it pleases me to think that the city watched him, felt the shimmer of his madness and genius in his slouching promenades along Meeting Street. I like to think of the city shaping this agitated, misplaced soldier, keening his passion for shade, trimming the soft edges of his nightmare, harshening his poisons and his metaphors, deepening his intimacy with the sunless wastes that issued forth from his kingdom of nightmare in blazing islands, still inchoate and unformed, of the English language.16

In the first passage, Will—an aspiring writer himself—describes the city in terms that evoke Poe’s Gothic fiction, as if viewing Charleston through a Poe-esque lens. But if Poe has colored his view of Charleston, in the second passage Will echoes Hervey Allen’s speculation in Israfel that the environment “shaped” Poe by darkening his perspective: again, the influence travels in both directions. Like the Charleston Renaissance writers, he imagines a personal kinship with Poe based on a shared physical environment. Conroy’s invocation of Poe, who otherwise does not play a role in the novel, provides a synecdoche for almost a century of mythologizing, willing Poe’s Charleston ghost into existence.

We still know almost nothing about what Charleston meant to Poe, who covered up his own connection to the Carolina Lowcountry—but clearly Poe has meant a great deal to Charleston since the 1920s. Simultaneously reverent and opportunistic, the Charleston Renaissance writers proclaimed Poe’s influence and placed him in a literary tradition they were in the process of creating. Down-at-the-heels nobility, mystical landscapes, and the belief that there is only one “kingdom by the sea”: Charlestonians have found in Poe their own, mostly flattering, reflection. It was as if Poe, like Captain Kidd in “The Gold-Bug,” had buried a treasure on Sullivan’s Island for enterprising writers and entrepreneurs to discover a century later. Since that time, Charleston and Sullivan’s Island have written Poe into their history and landscape, speculating and inventing when available facts prove insufficient. Their efforts have had the effect of self-fulfilling prophecy, creating a spiritual bond between Poe and Charleston by insisting that one already exists.

Scott Peeples is Professor and Chair of English at the College of Charleston. He has published numerous essays on nineteenth-century American literature and two highly regarded books on Edgar Allan Poe. Peeples is a past president of the Poe Studies Association and past co-editor of the journal Poe Studies. NOTES

- The Sullivan’s Island branch of the Charleston County Library is named for Poe, and there is a Poe Avenue, a Raven Drive, and a Goldbug Avenue on the island. For a provocative reading of the island’s appropriation of Poe, see Liliane Weisberg, “Black, White, and Gold,” in Romancing the Shadow: Poe and Race, ed. J. Gerald Kennedy and Liliane Weissberg (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 127–56; Poe did emphasize setting in two other tales located in places he lived: “William Wilson” (1839), set in Stoke Newington, where Poe attended school while living in London with the Allans; and “A Tale of the Ragged Mountains” (1844), set near Charlottesville, Virginia, where Poe spent most of 1826 as a student at the University of Virginia; The Collected Works of Edgar Allan Poe, vol. 3, ed. Thomas Ollive Mabbott (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1978), 817.

- See Arthur Hobson Quinn, Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography (1941; rpt. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998), 131–32; and Frank Durham, “Poe on Sullivan’s Island,” in The Gold Bug by Edgar Allan Poe (Charleston, SC: Tradd Street Press, 1969), 18–19.

- For more on the promotion of a southern Poe in the early twentieth century, see Scott Peeples, The Afterlife of Edgar Allan Poe (Rochester, NY: Camden House, 2004), 19–24, 128–34. See also, Thomas C. Carlson, “Biographical Warfare: Silent Film and the Public Image of Poe,” Mississippi Quarterly 52, no. 1 (1998–99): 5–16.

- DuBose Heyward and Hervey Allen, Carolina Chansons: Legends of the Low Country (New York: Macmillan, 1922). Subsequent quotations are from this edition; line numbers are indicated in parentheses. Allen’s poem “Alchemy” had been published previously in the North American Review.

- The Yemassee Lands: Poems of Beatrice Ravenel, ed. Louis D. Rubin Jr. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1969). Subsequent quotations are from this edition; line numbers are indicated in parentheses.

- David Ketterer, The Rationale of Deception in Poe (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1979).

- Edgar Allan Poe, Essays and Reviews, ed. G. R. Thompson (New York: Library of America, 1984), 19.

- Edgar Allan Poe, Complete Poems, ed. Thomas Ollive Mabbott (1969; rpt. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2000), 175.

- Louis D. Rubin, introduction to The Yemassee Lands, 27.

- Year Book of the Poetry Society of South Carolina (Charleston: Poetry Society of South Carolina, 1923): 67–68, 67. An illustration of the diorama appeared as the frontispiece to Mary Newton Stanard’s book The Dreamer: A Romantic Rendering of the Life-Story of Edgar Allan Poe (New York: Lippincott), when it was republished in 1925.

- Hervey Allen, Israfel: The Life and Times of Edgar Allan Poe (New York: Farrar and Rinehart, 1934), 171.

- William S. Hoole, “Poe in Charleston, South Carolina,” American Literature 6 (1934): 78–80. For the fullest account of Poe’s time in the military, see William E. Hecker, introduction to Private Perry and Mister Poe: The West Point Poems, 1831, ed. William E. Hecker (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2005), xvii–lxxv; W. Stanley Hoole, According to Hoole: Collected Essays and Tales (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1973), 121–23; Quinn, 129, 275; Robert Adger Law, “A Source for ‘Annabel Lee,’” Journal of English and Germanic Philology 21 (1922): 341–46.

- C. T. Leland, letter to the editor, (Charleston) News and Courier, October 10, 1968.

- E. V. H. [Elizabeth Verner Hamilton], postscript to The Gold-Bug by Edgar Allan Poe (Charleston, SC: Tradd Street Press, 1969), 77–78.

- Interview with C. T. Leland, July 28, 2008. A newspaper column by Jack Leland (Charleston Evening Post, January 20, 1982, B1) retold the story of Prof. Lenard “and one of his Latin students” discovering the grave marker with the initials “ALR” in the Unitarian Churchyard. He reports that “[t]heir plan was to select a suitable grave and then raise funds for a monument to the heroine of one of the world’s great romantic poems by one of America’s greatest writers,” and concludes by suggesting that the Poetry Society of South Carolina take up the cause; “Poe in Charleston and the Legend of Annabel Lee,” A Gothic Curiosity Cabinet, http://www.gothichorrorstories.com/classic-gothic-ghost-stories/poe-in-charleston-and-the-legend-of-annabel-lee/, accessed June 18, 2015; see also, Tom Crawford, “A Ghost by the Sea,” Ghost Source, http://www.ghostsource.com/hauntings/hauntings_ghostbythesea.php, accessed June 18, 2015; “Edgar Allan Poe—Sullivan’s Island Secrets,” The Elliott House Inn, http://www.elliotthouseinn.com/edgar-allan-poe-sullivans-island-secrets/, accessed June 18, 2015. See also, “Anna Ravenel and the Unitarian Church Graveyard,” Scares and Haunts of Charleston, https://scaresandhauntsofcharleston.wordpress.com/2012/03/15/anna-ravenel-and-the-unitarian-church-graveyard/, accessed June 18, 2015; and Donna M. Owens, “Chasing Poe’s Ghost in Charleston,” Baltimore Sun, October 9, 2014, http://www.baltimoresun.com/travel/bs-tr-charleston-poe-20141007-story.html#page=1, accessed June 18, 2015. J. W. Ocker also discusses the Annabel Lee legend and Poe landmarks on Sullivan’s Island in Poe-Land: The Hallowed Haunts of Edgar Allan Poe (Woodstock, VT: Countryman Press, 2015), 319–41.

- Pat Conroy, The Lords of Discipline (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1980), 1–2.