In fall 2017, Southern Cultures will publish a special issue on material culture. As we turn our attention towards objects and the meanings they hold, we share an essay by Marilyn Zapf, assistant director and curator, the Center for Craft, Creativity & Design, Asheville, NC.

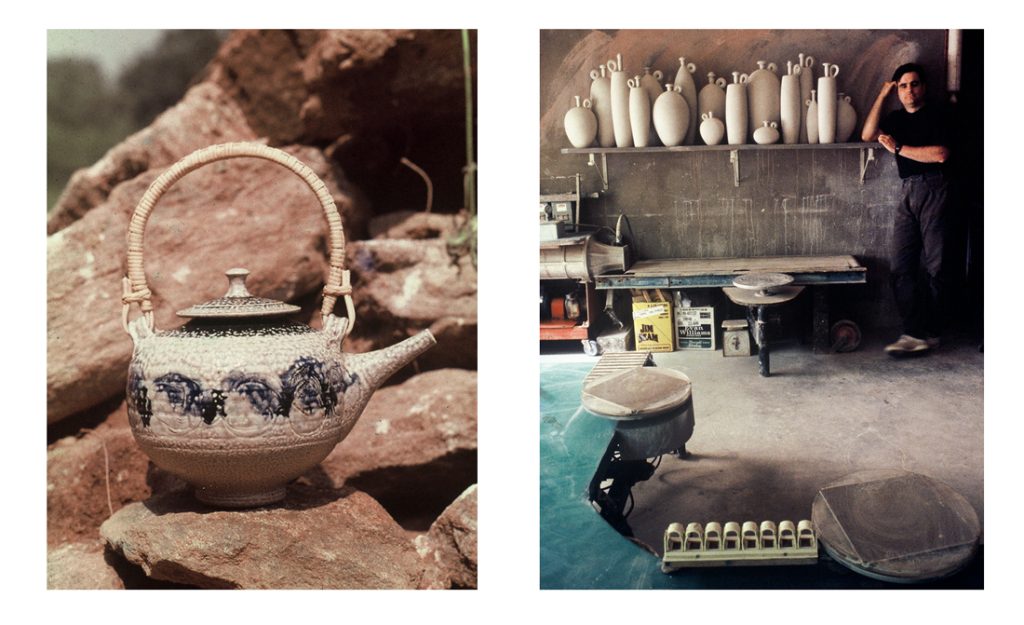

“Shortly after I set up my first studio, I asked Cynthia Bringle if I could visit her to talk about my work. She took the time to hear my story, look at my [ceramics], and discuss what was working successfully and what was not. Then, Cynthia generously opened her personal book of glazes and slips and showed me which ones she thought would be helpful with the glazing of my wares.

I sat on the back stoop of the studio and copied all of the information that she shared with me. When I finished, I thanked her and handed the book back to her. And this is the moment I remember so well: Cynthia took hold of that book, looked me straight in the eye, and said “Michael, I am happy to help. I have done this for you, now you go and make this part of what you do for others.”

—Michael Sherrill (emphasis added)1

The story of how studio craft emerged in western North Carolina is succinctly summarized for me in this account of the prominent clay artist Cynthia Bringle sharing her glaze recipes with a then young and aspiring ceramist, Michael Sherrill. Bringle plainly lays out a founding principle upon which the studio craft community in this region has been built: Pass it on. Whether sharing technical skills or an eye for aesthetics, business advice or life lessons, the willingness of artists to “pass it on” has produced a culture of respect for tradition as well as a welcoming and growing group of artists.

Western North Carolina has a long and vibrant history of craft to honor and respect, beginning with the traditional handwork of the Cherokee, continuing with the craft revival, and later including the studio craft movement. Today the region is home to one of the largest concentrations of craft artists within the United States. A 2008 study surveyed over 2,200 full- and part-time craft artisans residing and working in western North Carolina (a 198% increase from a similar 1995 study), identified over 130 craft galleries, and estimated the total annual economic impact of the professional crafts industry to be $206.5 million.2 And yet, despite the notoriety of western North Carolina artists, the large concentration of craftspeople, and the widely recognized role that craft plays in the economic development of the region, studio craft is still relatively new here.

Pursuing Excellence

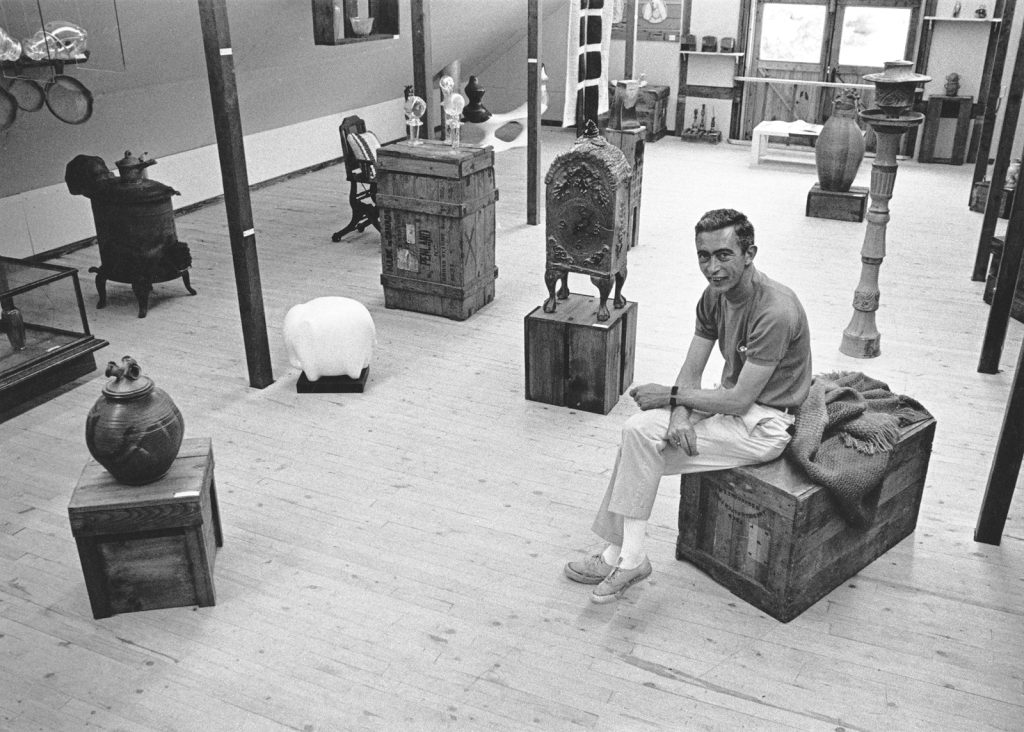

Ten years ago, The Center for Craft, Creativity & Design (CCCD) partnered with Blue Spiral 1 (BS1) to exhibit the first survey of studio craft in the region. Pursuing Excellence: The Studio Craft Movement in Western North Carolina highlighted 19 artists spanning the five major craft media—wood, fiber, clay, metal, and glass—who were making exceptional handmade, one-of-a kind objects.

Notably, not one artist in the original exhibition was born in North Carolina.3 Only three artists were born in the South (two from Tennessee and one from Virginia).4 The majority moved from the Northeast and Midwest to this region after the age of 30, predominantly settling here in the 1970s and 1990s.5 Examining the movement and timing of when these artists came to the region is important because it underlines the fact that beginning around the 1970s the first generation of studio craft artists were bringing skills and knowledge from elsewhere, plugging into a preexisting regional craft heritage, and establishing a new artistic community that continues to thrive and grow today.

Dean Allison, Rose Colored Reign, 2015. Cast glass; 23 x 13 x 14 inches. Private collection. Photo by Mercedes Jelinek. (On view in Forging Futures.)

Indeed, many of the artists put forward in this original survey show helped to establish studio craft as a defining marker of this region and paved the way for other artists to migrate here and set up their shops in the Blue Ridge Mountains. It is no wonder, then, that the Pursuing Excellence author Melissa Post sought to “illustrate the factors that have attracted these artists to the area” in her catalog essay, concluding that a combination of “community, environment, resources, and preservation” were among the main reasons artists moving to the area decided to remain.

Forging Futures surveys 24 artists shaping the future of studio craft in western North Carolina.

This exhibition, Forging Futures: Studio Craft in Western North Carolina, surveys 24 emerging and established artists shaping the future of studio craft in western North Carolina. It builds on the idea of Pursuing Excellence by incorporating a second generation of artists, demonstrating the power of a “pass it on” ethos in building community. Many of the emerging makers included in this show have trained with or been mentored by founding studio craft artists in this region, many of whom were in the first exhibition. In this sense, Forging Futures looks forward at the same time it looks backward. It is through this lens that I hope to first revisit western North Carolina in the 1970s and trace the rise of studio craft in this region through three prominent craft institutions, before examining the artists that are poised to shape the next iteration of studio craft in the region today.6

The Rise of Studio Craft in Western North Carolina

Studio craft—as opposed to traditional, production, DIY, or contemporary craft—is distinguished by the creation of handmade, one-of-a-kind art objects that reflect the maker’s artistic expression or point of view. With roots in both arts and crafts and the craft revival, the studio craft movement is generally thought to have begun in America post WWII due to the converging impact of the G.I. Bill, the expansion of art schools to include craft media, and the establishment of the American Craft Council and its publication Craft Horizons, among other factors.7 And although early signs of this movement can be found in western North Carolina in the 1960s, studio craft did not fully take root in the region until the 1970s.

Certainly some of the benchmark moments for craft in this region follow the expected studio craft trajectory, such as the proliferation of craft taught through university art programs. At Western Carolina University, the ceramist Joan Falconer Byrd was hired as faculty in the newly renamed Department of Art in 1968 and began building the reputation of a now well-known and respected ceramics program.8 However the unique history of the region, in particular, its connection to the craft revival, and its rural and (at the time) relatively undeveloped nature, created an alternative and highly local story of studio craft.

In some cases the movement transforms institutions founded as part of the craft revival, including Penland School of Crafts and the Southern Highland Craft Guild. In other cases new programs and organizations are formed in response to or alignment with the rise of studio craft, such as the Haywood Community College Professional Crafts Program. A closer examination of these three entities begins to trace the unique rise of studio craft in western North Carolina.

Penland

Located approximately fifty miles north of Asheville, Penland Weaving Institute—now Penland School of Crafts—originally built its reputation as a place where local Appalachian women were taught skills to earn or supplement family income. Hired in 1962, the school’s second director, Bill Brown, transformed Penland Weaving Institute from a site of heritage craft preservation to a bastion of the studio craft movement. He expanded the types of craft media taught at the school and began employing and attracting emerging artists as teachers and students respectively.

Mary Savig, curator of manuscripts at the Archives of American Art, succinctly explains, in her essay “Pillars of Penland,” the impact of Brown’s tenure.9 Beyond simply infusing Penland with an influx of studio artists, Brown is perhaps best associated with the establishment of a residency program in 1963. Through this program, not only did artists move to the region but also many of them—for example, Cynthia Bringle—stayed long after their residency was over, building a stable network of studio craft artists in the region.

Southern Highland Craft Guild

Like the Penland Weaving Institute, the Southern Highland Craft Guild was established during the craft revival and went through an institutional transformation in the 1960s and 1970s due to the arrival of studio craft. Chartered in 1928 by Frances Goodrich, the Guild was a cooperative that sought to educate mountain craftspeople and provide a marketplace for their wares.10 However, by the 1970s, not only were the markets for craft shifting (the Guild moved both their July and October fairs to Asheville, North Carolina in 1978) but the type of craft artist in the region was shifting as well. As studio craft artists moved to the mountains, they became members of the guild, redefining the organization from one that promoted heritage mountain crafts to one that promotes the work of multiple types of craft in the region.

Unlike Penland, which shifted from teaching production heritage crafts to promoting the making of one-off studio craft objects, the Guild maintained its ties to mountain crafts, and the two art forms were asked to coexist under the same organization. Thus, traditional coverlet weavings were promoted and sold in the same venue as contemporary sculptural pottery. Often, differing artistic visions for the organization were worked out in the Standards Committee, whose charge was to set the standards for new members to be accepted into the Guild. Membership is based on a jury process that requires an application, image, and object review. Even today applicants must apply under one of two memberships classifications: general or heritage.

The Guild became an important institution for studio craft because it provided an outpost for artists that did not move to the region via Penland. Their annual meetings and fairs provided the opportunity for makers to sell their work, share skills through demonstrations, seek inspiration through exhibitions, and find other artists seeking to make a living from their work. It was a hub of shared knowledge and artistic community.

Haywood Community College

Another key component of the growing studio craft community in western North Carolina was the establishment of the Haywood Community College’s Professional Crafts Program in 1977. Still in operation today, the Professional Crafts Program was revolutionary for combining the teaching of technical craft skills with the business know-how needed to make a living as a craftsperson.

Seeds of the program were planted when Gary Clontz was hired in 1974 to start a production pottery program modeled on a similar curriculum written for the Montgomery Community College (near the well-known pottery production centers of Seagrove and Jugtown, North Carolina). A few years later, the program grew into a comprehensive studio craft program with the addition of faculty in wood, fiber, metal, and, later, design. Over the years a core faculty would come to include the studio furniture maker Wayne Raab, the textile artist Catharine Ellis, the metalsmith Arch Gregory, and the design instructor Bob Gibson.

Illustrating the still-forming community of craft during the 70s, the founding teachers recall how most students came either from out of state or from other parts of North Carolina. There was not an active craft community in Waynesville at that time. Today, approximately 10% of the current Southern Highland Craft Guild membership is made up of Haywood graduates.

Through their teaching, personal craft practice, and community service Clontz, Raab, Ellis, Gregory, and Gibson modeled for hundreds of students what it means to be part of a craft community. All were members of the Guild at some point during their career, and many served Guild committees. Clontz became the president of the board from 1998 to 2001 and from 2015 to the present. In addition, Ellis was a founding board member of Handmade in America, served on the boards of The Center for Craft, Creativity & Design and Penland School of Crafts, and in 2012 established the Western North Carolina Textile Study Group.

And…

In addition to Penland School of Crafts, the Southern Highland Craft Guild, and Haywood Community College, there are many other institutions, people, and locations that factored into making this region a home for studio craft. Organizations such as Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts, John. C. Campbell Folk School, Handmade in America, Energy Xchange Incubator, and Piedmont Craftsmen are vital to building such a strong craft community, not to mention historical craft production sites such as Seagrove, Jugtown, Brasstown, and the Toe River Valley. And unlike many other regions of the United States, where studio craft sprang from university art school programs, this region exhibits a more grassroots transformation. The proliferation of community, opportunities, and organizations quickly distinguished western North Carolina as a refuge and incubator for studio craft.

Forging Futures

“Working for Hoss Haley was more than a job—it was a priceless education and the start of an ongoing dialog of art, craft, career, and life that continues today.”

—Andrew Hayes11

We are only now beginning to see a second generation of studio craft artists emerge in this region. Some were born here, like Alex Bernstein and Hayden Wilson, their parents being among the first wave of glass artists to settle in the region. Some are continuing the legacy of institutions begun during the studio craft movement. For example, Amy Putansu recently took over for Catharine Ellis to lead the Haywood Professional Crafts Fiber Program, and Heather Mae Erickson is following Joan Falconer Byrd as head of ceramics at Western Carolina University. Many continue to find their way to the area through the Penland Residency and Core Fellowship Program, including Dean Allison, Dustin Farnsworth, Andrew Hayes, Rachel Meginnes, Jaydan Moore, Zach Noble, and Tom Shields. Still others, like Jessica Green, move here because they are inspired by the regional craft history, attracted by the artistic community, and stimulated by the “pass it on” mentality.

It should be noted that the “pass it on” culture is about not only intergenerational mentoring but peer-to-peer learning as well. Artists like Josh Copus and Eric Knoche, among others, have reflected on the importance to their studio practice of working side by side with colleagues. Copus recalls how “Eric Knoche and I spent eight years working in Clayspace together… We grew up together as artists and learned so much from each other. Eric is my peer, but he is also one of my greatest teachers and many of the most valuable lessons in this life I learned with him.”12

Meanwhile, the first wave of artists who moved to the region have established community and modeled for a next generation different modes of “passing it on.” Artists like Elizabeth Brim, Lisa Clague, Mark Peiser, and Pablo Soto teach workshops at Penland. Others continue to be active members of the Guild, including Kathy Triplett and Brian Boggs. Still others, such as Hoss Haley, Michael Sherrill, Stoney Lamar, and George Peterson, have set up studios where younger artists can assist, apprentice, and intern. Most of these artists’ current practice involves a combination of teaching, mentoring, and community building.

The secret that Bringle didn’t tell Sherrill about “passing it on,” at least not overtly, is that the teacher-student or mentor-apprentice relationship is not a one-way street. The “master” does not simply pass on knowledge to pay it forward, settling up on a debt of knowledge received. In a 2012 CCCD Craft Think Tank on apprenticeships, mentors articulated the “vitality of participating in an intergenerational community,” the value of “interplay [between] new ideas and older tradition,” and how “having assumptions challenged by a younger person” pushed their own body of work forward. The act of sharing becomes part of a lively creative relationship. It is this back-and-forth that occurs in the act of “passing it on” that forged the studio craft community in this region and gives me a reason to believe the next generation of artists will carry this legacy forward.

Forging Futures: Studio Craft in Western North Carolina is on view at Blue Spiral 1 in Asheville, North Carolina between June 29 and August 25, 2017.

Marilyn Zapf is the assistant director and curator at The Center for Craft, Creativity & Design (CCCD) in Asheville, NC. Zapf has organized 15 and curated 9 exhibitions for CCCD’s Benchspace Gallery, including the nationally-traveling Made in WNC (2015) and Gee’s Bend: From Quilts to Prints (2014). Outside of the office, Zapf is an independent curator, teacher, and writer. She is currently working on an upcoming exhibition for the Mint Museum of Craft + Design (2018). She holds a MA in the History of Design from the Royal College of Art and Victoria and Albert Museum in London, England, and a BA (English Literature) and BFA (Jewelry and Metalworking) from the University of Georgia. Her areas of research include craft, postmodernism and de/industrialization.

Header image: Alex Bernstein, Aqua Steel Shadow, 2015. Cast and cut glass with fused steel; 20 x 21 x 3 inches. Private collection. Photo by Steve Mann.